When the SF Municipal Transportation Agency board voted Tuesday to approve some speed limit reductions, it looked like a modest initiative: The busier portions of seven streets in neighborhoods across the city would see their top speeds reduced to 20 or 25 miles per hour.

But the changes, effective in January, reflect both the culmination of a long legislative advocacy campaign and the beginning of what promises to be a lengthy and iterative process of transforming the pace of city traffic.

The new look at speed limits is a product of a new state law, AB43, which allows municipalities to reduce speeds by 5 miles per hour in designated business or safety corridors where traffic is ‘faster than safe or reasonable.’ California cities had previously been hamstrung by the state Vehicle Code, which dictated that speeds be based on what is called the ‘85th percentile speed (opens in new tab),’ or the speed at or below which prevailing traffic moves on a given street.

San Francisco in 2014 adopted a traffic safety goal based on the Vision Zero (opens in new tab) policy concept: eliminating traffic deaths by 2024. But the city has made little progress, and the Covid-19 pandemic hasn’t helped. The overall decline in activity during Covid lockdowns did mean fewer traffic injuries, but deaths remained high (opens in new tab): According to the city’s dashboard (opens in new tab) on traffic fatalities, there were 31 in 2014, compared with 30 in 2020 and 24 so far this year.

Speed is a huge factor in the outcome of a traffic collision: Research (opens in new tab) has consistently shown that the probability of death from a vehicle collision increases with speed, and that the magic number – the speed that most reflects the threshold between mere injury and death – is 20 miles per hour.

In 2018, the state legislature established a state Zero Traffic Fatalities Task Force (opens in new tab), which included local transit advocates such as Leah Shahum, a former director of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition and founder of the Vision Zero Network; Kate Breen of the SFMTA, and Dave Snyder, another former SF Bicycle Coalition director.

Among the findings released by the task force in 2020 was that the ’85th percentile’ rule, described as (opens in new tab) ‘an approach developed decades ago for vehicles primarily on rural roads,’ was in urgent need of change. The result was AB43.

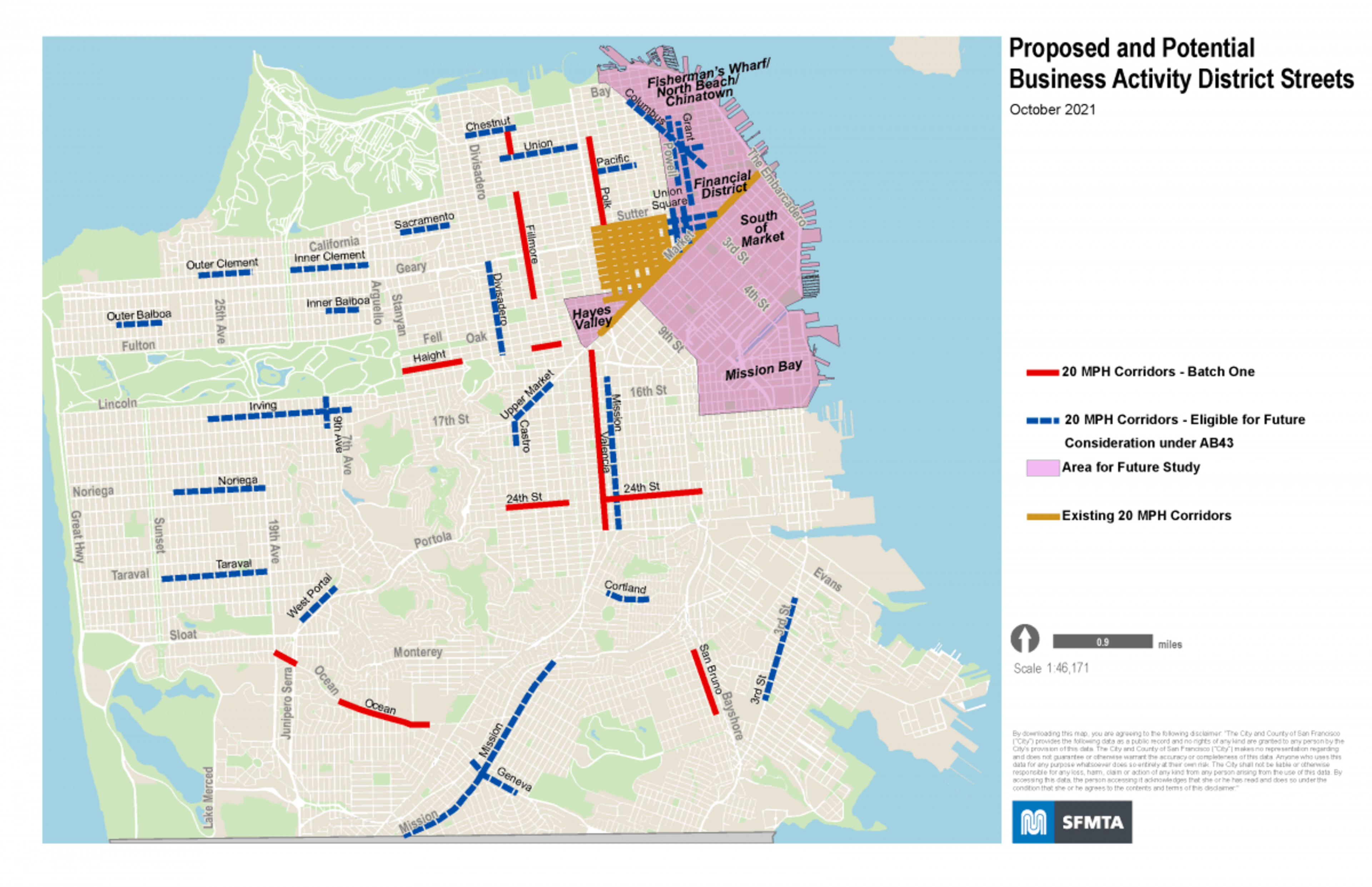

The SFMTA’s move this week affects seven streets in Noe Valley, the Marina, the Western Addition, the Haight-Ashbury, Polk Gulch and Russian Hill, Ingleside, Lakeside, Portola and Mission. They represent what SFMTA calls ‘key business activity districts,’ where at least half of property uses are businesses open to the public.

But there’s more to come. The next phase includes streets which are part of what SFMTA describes as the city’s ‘High Injury Network (opens in new tab):’ 13% of the city’s streets, where 75% of severe traffic injuries and fatalities happen. These streets will have their speed limits reduced to 20 mph.

A significant nexus of the High Injury Network is the Tenderloin (opens in new tab), where earlier this year SFMTA implemented 20 mph speed limits on 17 corridors, using a loophole in state law. AB43 will allow for more permanent solutions for new locations starting in June 2024, when Caltrans establishes its own definitions for what it will call ‘safety corridors.’

Advocates, however, want even faster implementation. “These commercial corridors are the heart of our communities and should be calm, safe places for walking and gathering… the seven locations are a great start to enacting AB43, but we can’t stop there… we’re asking the SFMTA Board to request that the additional 35 identified locations be brought forward by April 2022,” said Brian Haagsman, Vision Zero organizer for WalkSF, before this week’s vote.

Rachel Clyde, a staffer at the SF Bicycle Coalition, said: “Slower speeds are one of the easiest ways to make our streets more welcoming and safe for bicycling and walking, and we strongly encourage the city to follow these changes up with better street design, and creative street activation, and not implement these changes through traffic enforcement.”

Clyde’s statement also reflects one of the trickier aspects of the new scheme: enforcement. SFMTA is relying on passive enforcement, such as prominent street signs and speed cameras.

Meanwhile, stakeholders who rely on driving are receiving the changes with a combination of resignation and skepticism.

“I consider this inevitable, I think [taxi drivers] can live with it, and it makes sense on the streets they’ve chosen so far… but it’s going to require more police, so I don’t know if it will work at first due to the shortage of motorcycle cops… in the long run it might help,” said Barry Taranto, a spokesperson for the San Francisco Taxicab Workers’ Alliance.