Martha Garrido, a domestic worker in San Francisco who has worked in the industry for 15 years, has to navigate the intricacies of working with six individual employers on a regular basis.

That was before the pandemic led many of her clients to drop her services.

In February, Garrido slipped while working and broke her hand, leaving her unable to work for six weeks. While she had some cash stashed away in case of emergency, Garrido’s employer failed to pay her for any sick days, as required by San Francisco law.

“I pay my taxes every year and I hope to have a pension someday. However, I do not have sick leave benefits for illnesses or emergencies. I can take time off if I get sick, but I don’t get paid,” Garrido said through a Spanish translator at a Dec. 8 Board of Supervisors committee meeting. “My hand hurts from arthritis that was caused by repetitive work over the years, but when I can’t go to work, I don’t get sick pay.”

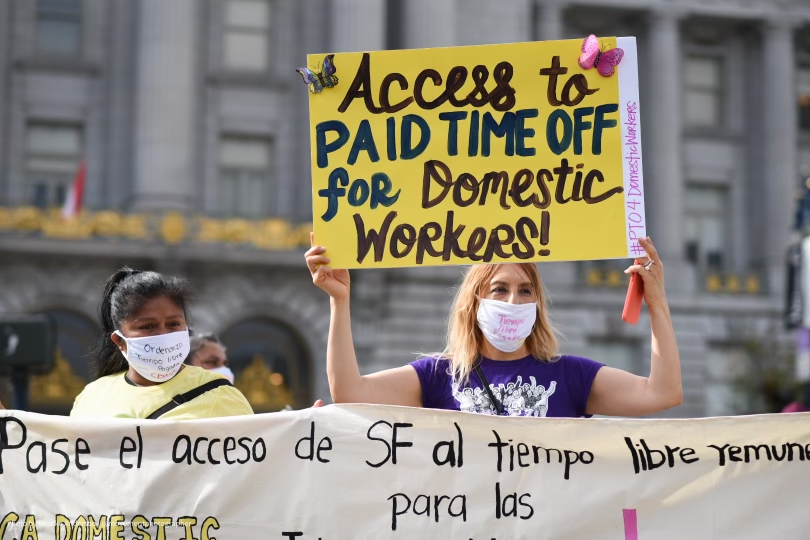

To support workers like Garrido, San Francisco has approved a novel system to guarantee paid sick leave for the roughly 10,000 domestic workers in the city, including home aides, nannies and house cleaners who often labor in less formal structures prone to exploitation.

The ordinance, introduced by District 9 Supervisor Hillary Ronen and drafted with the California Domestic Workers Coalition, is meant to help employers meet their legal mandate to provide at least one hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours of work through a smartphone-based app. Employers who already abide by the paid sick leave law are exempt.

By creating a system for employees to track their hours, the idea is to arm the Office of Labor Standards Enforcement with visibility into the labor patterns of domestic workers and the ability to track employers who don’t pay their fair share.

“Although they have the right to paid sick leave, in reality very few domestic workers have the ability to access it,” Ronen said at Tuesday’s Board of Supervisors meeting, where the measure was unanimously approved. “If this works it could be replicable in many other industries as well.”

The system is being designed as a “portable benefit,” meaning it is not connected to a specific employer. The app, slated to be released in late 2022 or early 2023 after a design and procurement process led by the Office of Economic & Workforce Development, will track the accrual of the paid sick leave across multiple employers and pay out appropriate benefits.

Both the employee and employer will use the app, which will likely be developed and administered by a third party. A domestic worker would use the system to log their hours across multiple employers, while an employer will use the app to pay into sick leave benefits, with the transfer of funds facilitated by the technology.

Although the program is a single patch in the limited social safety net for domestic workers, proponents say it could be the first step in a larger sea change led by local governments like San Francisco to build an alternate and portable system of employment benefits.

“We hope this is just the tip of the iceberg as far as bringing benefits and the like to groups that have been historically left out,” said Santiago Lerma, an aide for Ronen.

Cities Lead the Way

The term “portable benefits” was coined in a 2015 Medium post signed by a long list of business and labor leaders, but the concept dates back to New Deal policies like Social Security.

More recently, the idea has come into vogue with the growth of gig work. Around 10% of workers in the country rely on “non-standard” work arrangements ranging from temp agencies to rideshare transportation to domestic work.

“The prototypical model of benefits – i.e. those offered by a company for their employees during their tenure – no longer suffice when workers are increasingly unmoored from the company structure,” according to a December report from the Aspen Institute, a nonpartisan think tank.

Isaac Jabola-Carolus, a researcher with the City University of New York who has studied domestic workers in San Francisco, found that the median age for domestic workers in the city is 50 and their median pre-tax income hovers around $19,000, less than other low income occupations like retail workers, waiters and janitors.

The workforce is around 90% women and nearly 75% were born in countries outside of the U.S. Jabola-Carolus research showed that only 28% have been able to access paid time off under San Francisco’s Paid Sick Leave Ordinance.

He said that an important future step for the local domestic work industry could be providing retirement savings plans through a portable benefits system.

“About 90% of surveyed San Francisco domestic workers lack retirement savings, so such a program would have a profound impact,” Jabola-Carolus wrote in an email.

In a recent example of this type of expansion, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul signed legislation into law in October that requires private sector employers with 10 or more employees who don’t already have a retirement plan to automatically enroll their employees in the portable New York State’s Secure Choice Savings Plan.

Shelly Steward, director of the Aspen Institute’s Future of Work Initiative, said she’s buoyed by the initiative in San Francisco and similar efforts in cities like Philadelphia, which established a bill of rights for domestic workers that included a legal right to a portable paid leave program.

“It’s really inspiring to see smaller local governments like San Francisco act in the interests of the most marginalized workers and the workers who have been left behind the most because that’s how we’re going to have a more inclusive economy,” Steward said.

The SF app could provide a strong foundation for additional benefits, Steward added.

“It’s a great step to start with a single benefit. Say, how do we make sure every worker has access to paid sick leave? Then, what’s next? How might we think about scheduling practices or overtime pay or ensuring minimum wages are enforced?” Steward said.

She drew a sharp contrast to the kind of portable benefits offered by tech platforms like Uber or Doordash, which were created as a trade-off allowing the companies to continue classifying workers as independent contractors and therefore keeping them ineligible for traditional benefits.

“The key difference is that domestic workers who are covered by this portable benefits legislation are not having to give up rights in order to get these benefits,” Steward said.

For Everyone’s Benefit

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the lives of domestic workers even harder–and underscored their need for benefits.

“We saw that domestic workers overnight lost the majority of their work and of them became ill or their families or their children were infected by the virus,” said California Domestic Workers Coalition Director Kimberly Alvarenga.

Steward said the COVID-19 pandemic had cast a bright light on fissures in the social safety net, while also highlighting the ability of government and employers to provide rapid aid to workers in an emergency. That creates an opportunity to work towards a system envisioned by Steward and her colleagues where portable benefits are offered to everyone who works.

“When you have universal portable benefits you have that basic level of security and you also have a more dynamic labor market. Steward said. “If people have a job that is not serving them, a bad job, a low quality job, they can quit and move on and those benefits continue and carry with them. If someone wants to start a new business, take on an entrepreneurial endeavor, they can do that.”

A key consideration, Alvarenga underscored, is making tools as accessible as possible for both employees and employers and having oversight to ensure that the program serves its intended purpose.

“Policies may look good on paper, but they are really not real until they feel real in the lives of the people,” Alvarenga said.