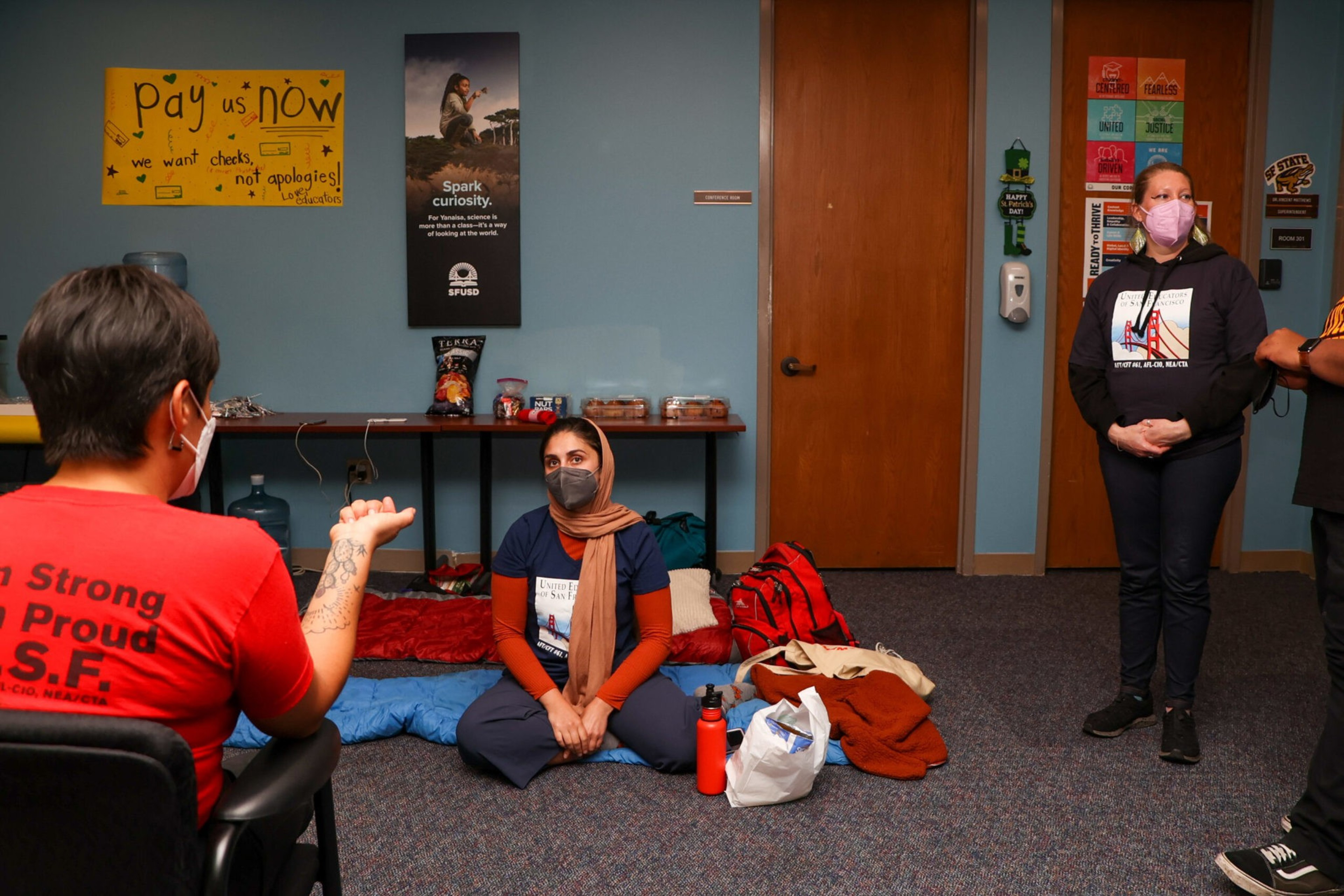

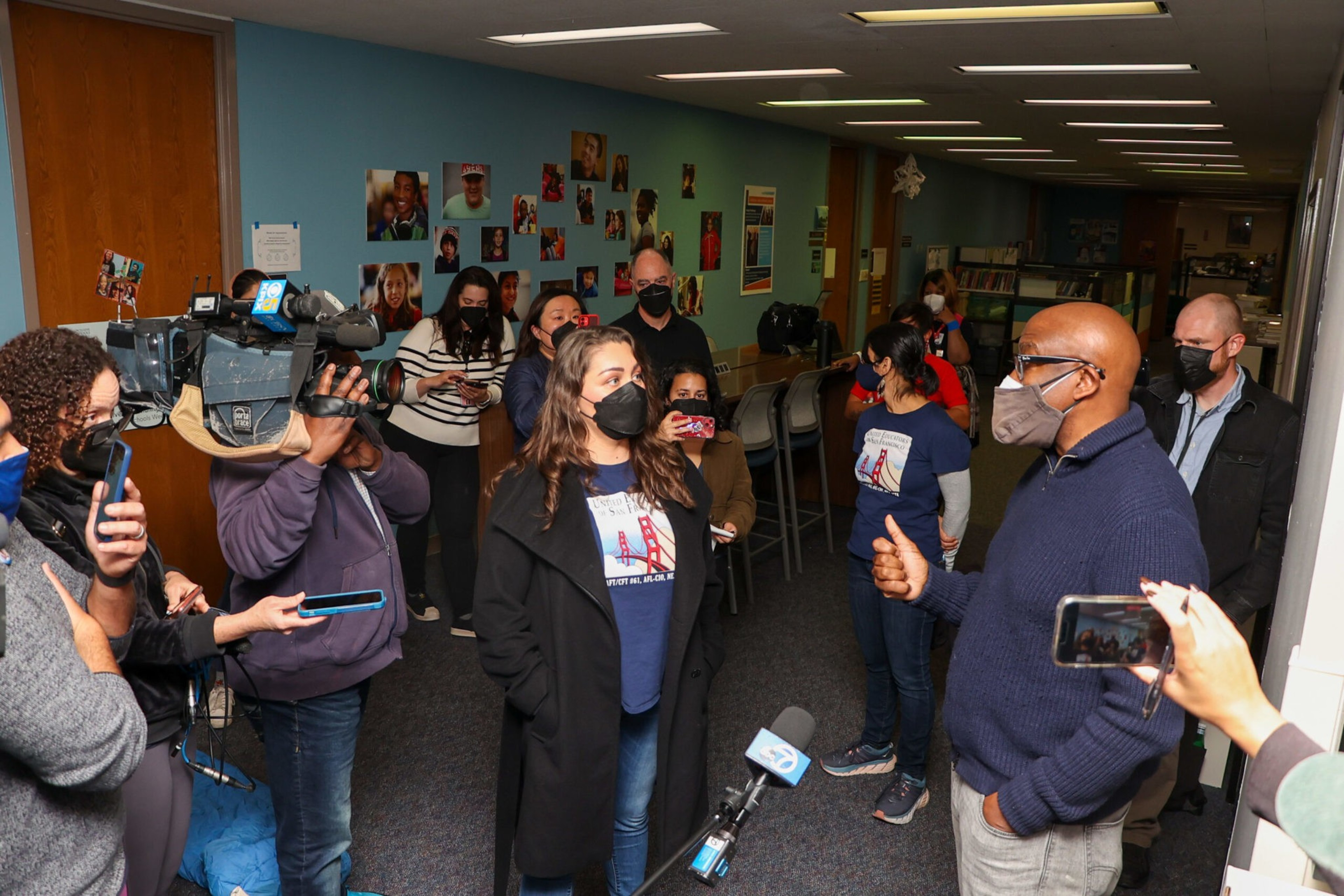

It’s been two weeks since the United Educators of San Francisco agreed to call off a four-day, round-the-clock occupation of the San Francisco Unified School District headquarters after administrators finally made good on roughly 1,000 underpayments, incorrect payments and missing paychecks.

But the dust is far from settled. One teacher said on Thursday (opens in new tab) that a preemptive look at April paystubs showed zero pay for some, while others say their tax withholdings have yet to be fixed (opens in new tab).

District staff estimated last week that righting the wrongs caused by the rocky rollout could cost as much as $300,000. Many more want to know how the district could have allowed the bureaucratic nightmare, which ostensibly stemmed from the January introduction of a new payroll system, dubbed EMPowerSF, to drag into March.

A post-mortem analysis of the system is scheduled to come before the Board of Education’s budget committee on April 6. In the absence of an official report, The Standard enlisted Omid Ghamami, president of Purchasing Advantage (opens in new tab)—a public- and private-sector procurement consulting firm—to take a detailed look at the contract and what may have gone wrong.

Ghamami, “the godfather of negotiation planning” according to his website, was cautious about passing judgment. He said oversights are common in negotiations between public agencies and private tech contractors and emphasized that even the most talented teams seldom finish software transitions on time or under budget.

Still, he observed that certain technicalities written into the agreement (opens in new tab) may have set EMPowerSF up for a very rough launch. One example: The vendor, Infosys, did not have a contractual responsibility to remedy issues with the system. Another factor Ghamami flagged: SFUSD, not Infosys, was responsible for migrating data between the old system and the new.

Ultimately, Ghamami saw no evidence that Infosys was ever in breach of contract (the district has said it doesn’t fault the contractor), suggesting that the fundamental issue with EMPowerSF was less about the services Infosys delivered and more about the company’s contractual obligations, as defined by the district.

“The vendor may have done exactly what it was asked [but] what they were asked was flawed, incomplete or inaccurate,” Ghamami said.

A Bumpy Beginning

The district first produced a request for proposal, or RFP, to upgrade its former payroll system back in 2017. Under the old system—initially adopted nearly 20 years ago and which district administrators described as “antiquated”—employees submitted paper timesheets and had to come to the central office in person when notifying the district they had changed addresses.

In October 2018, the district acknowledged in a presentation (opens in new tab) that the payroll project “started with a proposed scope that did not align to our resources” and one year later, scaled back the package to one with SAP SuccessFactors, a software company headquartered in South San Francisco, for a total of $5.9 million through 2024 (opens in new tab). SFUSD ultimately sent out another RFP in 2019 (opens in new tab) to implement the software.

Ghamami credits the district’s 2019 RFP for clearly laying out project objectives—a critical step that is often missed in negotiations like these, he said—and for breaking down evaluation criteria by percentage. He also said SFUSD was smart to spell out that “payment does not imply an acceptance of work” after settling on a contract with Infosys through the second RFP process.

But, he continued, the district should have been more explicit in tying payment to the performance metrics mentioned in the contract, which struck Ghamami as largely subjective. He also said it was a “red flag” that the district granted two additional pay increases to Infosys (opens in new tab), even though the contract stated that SFUSD would not pay more than the original amount of $9.5 million.

The contract also specifies that payroll functions like state taxation and timesheets would not be included. Ghamami noted that these could have contributed to related errors.

“Here you’ve got a component of payroll out of scope, and then it appears payroll is what went wrong,” Ghamami said.

Furthermore, the contract does not require that Infosys fix issues with EMPowerSF. While the district can withhold payment, threaten to end its agreement or conduct its own repairs and seek reimbursement, Infosys is not on the hook to address defaults in the contract itself.

Such a requirement would have been preferable, according to Ghamami. The idea that the district could fix problems that arise with EMPowerSF on its own and then be reimbursed assumes the district has the wherewithal to make such repairs in the first place.

The financial consequences of all this are just now becoming clear. According to the agreement reached between the district and the teachers union at the end of the three-night takeover, the district must pay for penalties incurred as a result of late payments and interest on missing pay. District staff estimated last week that the cost to right wrongs of payroll errors, including hiring more staff, could be as much as $300,000.

The original contract included six weeks of “hyper care,” which entailed having the consultants resolve issues that popped up after EMPowerSF went live. It was scheduled to end Feb. 18, but has been extended through the end of March, at no extra cost. Transitional support is supposed to continue through August, according to district spokesperson Laura Dudnick.

So who is responsible for setting the district up for a good or bad contract?

“It’s usually people who are very close to the work, who are defining the business requirements,” Ghamami said. Staff handling contracts are “contract experts; they’re not payroll experts. The people who were actually supposed to be rolling up those sleeves and defining the business requirements, that’s who’s responsible.”

District Accountability

A closer look at the contract doesn’t answer the fundamental question of why processing payroll went haywire. Infosys declined to comment.

“At this time, we believe that errors we are experiencing are not the direct result of the vendor’s performance,” said SFUSD spokesperson Laura Dudnick. “We continue to investigate and learn every day.”

Myong Leigh, deputy superintendent of policy and operations and a district staffer since 2000, was repeatedly cited by union leaders as the official responsible for the debacle during the sit-in.

Leigh, who oversees the big tasks of payroll and budget, was on the team that spearheaded the EMPowerSF transition, along with leaders from the technology, budget and human resources departments.

“I think that it’s a systemic failure just as structural deficit is a systemic failure,” said UESF secretary Leslie Hu on the first night of the sit-in. “And I also think that there are people who are responsible for this. I don’t know what their story is…but it’s hard to escape the fact that Myong is in charge of these two things that have really gone wrong in just the last couple of months.”

Leigh did not immediately return calls seeking comment. The district did not respond on behalf of Leigh or clarify which staff were tasked with implementation.

Board of Education Commissioner Ann Hsu sees two fundamental failures: preventing the crisis and addressing it once it happened. Without seeing the contract details, Hsu listed some of the same factors leading to disaster as Ghamami, like defining the scope of work and details, or not understanding how the previous system had run for a new system to handle.

“Whatever it is, if it’s not Infosys’ responsibility, or partly, then it is our responsibility and our management’s failure,” Hsu said. “The district needs to be held accountable. Somebody needs to be held accountable for this.”