Gallery of 9 photos

the slideshow

As the June 7 election (opens in new tab) draws near, there may be two reasons for civic-minded San Franciscans to go to City Hall.

One: to vote. The other: to take in the work of “Golden Decade (opens in new tab)” photographer David Johnson, whose black and white photography of civil rights activism, the Fillmore in its jazz era heyday and slices of San Francisco life from the 1940s to 1960s now line the ground floor walls leading up to City Hall’s voting center.

Titled David Johnson: In the Zone (1945-1965), the photography exhibition features a selection of 65 photographic works from UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library and is a celebration of Johnson’s oeuvre as a documentarian of Black life in San Francisco and the civil rights movement.

“So we’re taking a look at the history of San Francisco with the living legend still with us,” said Meg Shiffler, galleries director for the San Francisco Arts Commission. “And just happy to be celebrating here at City Hall with him.”

Johnson, now 95, broke barriers as the first Black student of famed landscape photographer Ansel Adams at the California School of Fine Arts, now the San Francisco Art Institute, in the 1940s. (The story goes that Johnson wrote to Adams after serving in the Navy during World War II to inquire about the art school’s photography program. “I said, ‘Dear Mr. Adams: I’m interested in studying photography. … By the way, I’m a negro,’” Johnson recalled in an interview with the library at UC Berkeley (opens in new tab). Adams replied that race was not an issue but that the class was full. When a spot opened up, he invited Johnson to attend; Johnson even stayed at Adams’ home for a time.)

The photos that came out of Johnson’s studies under Adams and other notable photographers of the time like Minor White, and afterward, encapsulated the vibrant atmosphere of the Fillmore during its heyday as the “Harlem of the West (opens in new tab),” but also everyday slices of San Francisco life, like men getting their hair cut at the neighborhood barbershop or children playing hopscotch.

“I learned my craft from Ansel Adams and yet it was The Fillmore that gave my work soul,” says Johnson in a didactic for the exhibition.

“It’s a record of a time that was not photographed too deeply,” said Shiffler, “and a really important time in San Francisco.”

Johnson not only snapped photos of celebrities like Eartha Kitt and Nat King Cole playing local venues—sometimes while on assignment as a photographer for the Sun-Reporter—he also photographed intellectual luminaries like W.E.B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes, as well as local activists, and politicians like Willie Brown.

“David was really more interested in capturing the crowd than the musicians a lot of times,” observes Shiffler.

“He wasn’t there to photograph the band,” added Jeff Gunderson, an expert on Johnson’s photography and a librarian and archivist for the Anne Bremer Memorial Library at the San Francisco Art Institute. “He was there to photograph the ambiance of it all, and the energy of it all.”

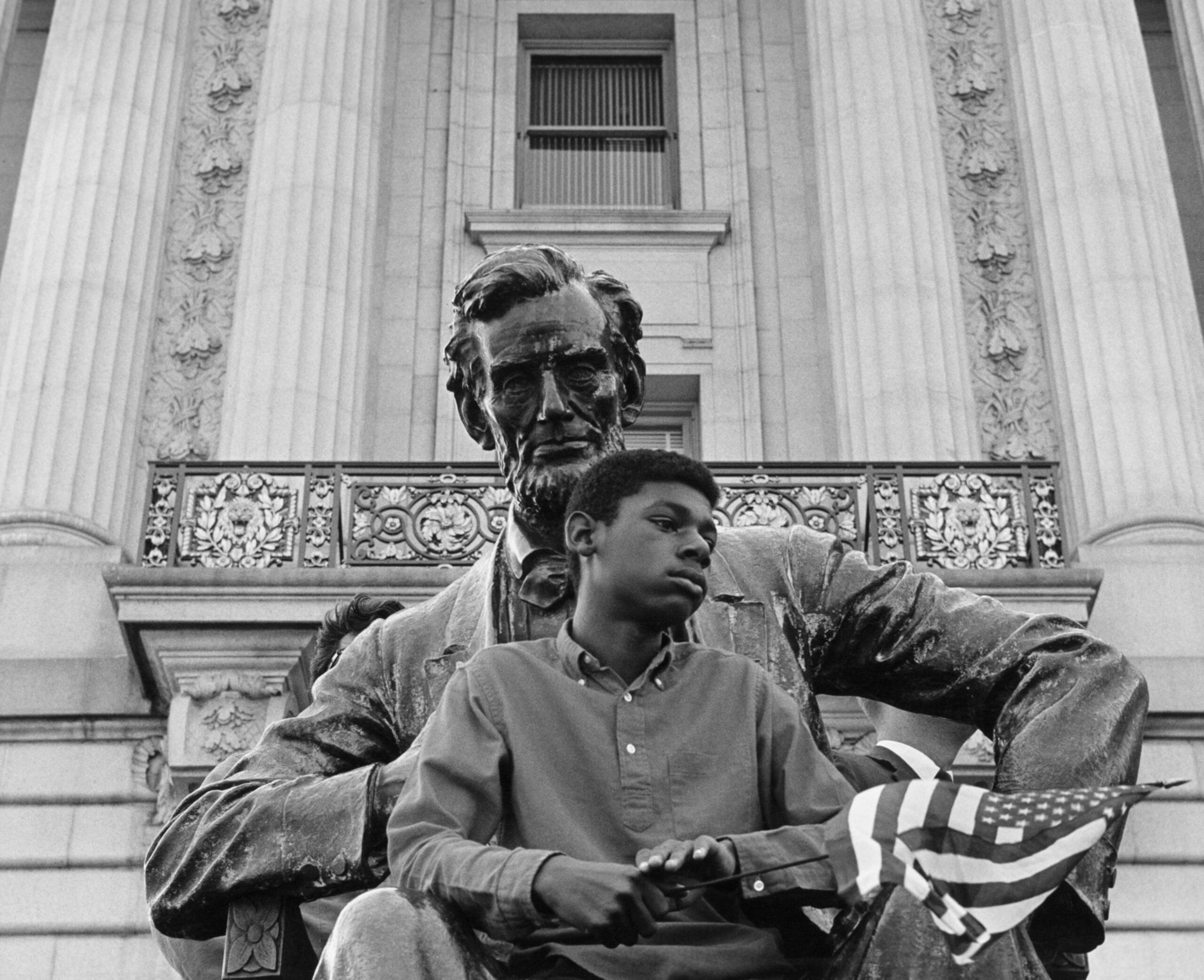

The same goes for Johnson’s photographs of civil rights rallies and demonstrations —among them a young boy with an American flag sitting in the lap of the Abraham Lincoln sculpture (opens in new tab) in front of City Hall and an elegant hatted woman also in front of City Hall (opens in new tab).

“One of the interesting things about David’s photographing of the civil rights movement is that he would go to a parade and take some photographs of the parade, but he was much more interested in the people who attended,” said Shiffler. “In this show, you’ll see him really being very interested, not just in the celebrity, but in the audience at the jazz clubs or the people in front of City Hall.”

“It’s American history, and it’s San Francisco history,” said Jacqueline Annette Sue, Johnson’s wife and author of the coffee table book of her husband’s photography, A Dream Begun So Long Ago. She spoke on his behalf by phone with The Standard. “The things that he documented in all areas… we will never see again except but through the lens of his camera.”

Shiffler hopes that the retrospective of Johnson’s photography at City Hall not only highlights his work as a photojournalist and documentarian but also as a “civic leader” in his own right. In addition to running his own photography studio on Divisadero for a time, Johnson was an organizer of the postal workers’ union, co-founded the first Black Caucus at UCSF, ran for San Francisco County Sheriff and became a social worker later in life.

“David was an activist, always has been an activist,” said Sue.

Ultimately, Shiffler hopes that Johnson’s photographs can be a starting point for viewers to reflect on their own civic duties, activism and the social justice movements of today around racial injustice, systemic racism, oppression and Black Lives Matter.

“I think a lot of these images around protest are actually really resounding today with the movements that we have going on,” said Shiffler. “That is part of our contemporary dialogue right now…to actually look at the past and think about how far we’ve come, but think about how far we have to go.”

‘David Johnson: In the Zone (1945-1965)’ is on view on the ground floor level and the North Light Court of City Hall through Jan. 6, 2023. A public artist reception will be held on Wednesday, May 25, from 5 to 7 p.m. in City Hall’s North Light Court. RSVPs are not required, but encouraged. Sign up at eventbrite.com (opens in new tab).

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect the correct name of Melrose Records, the correct spelling of saxophonist Louis Jordan’s name and the correct location of the “We Demand” march, which was held in San Francisco.