Until this spring, Matt Dorsey spent the bulk of his career selling San Franciscans on the ideas of others. By the time a press statement or an op-ed under his control made its way out the door for public consumption, Dorsey’s fingerprints had usually been wiped clean. People inside the room always knew better.

As a deeply embedded political consultant, a spokesman of 14 years with the City Attorney’s Office, a two-year head of strategic communications for the police department and now an appointed supervisor running in November’s election, Dorsey knows where the bodies are buried and how to sell a story.

“In a democracy,” Dorsey said in an interview this month, “communications is governing.”

His writing career started at Emerson College, where he learned how to influence public opinion as a campaign operative and ghostwriter. Over the course of three decades, his words have been relayed by a slew of San Francisco politicians and public agencies looking to control the narrative, and his strategic advice has often extended beyond the departments in which he works.

“I have to tell you, he was much more than simply a communications person,” said Dennis Herrera, the former city attorney and current head of the city’s Public Utilities Commission. “He was part of my leadership team. He worked with all of our lawyers on some of the biggest legal issues of the past two decades.”

Dorsey’s writing typically combines a keen eye for details, dashes of empathy—he is almost universally regarded as a nice person—and a heavy dose of bravado. Projecting confidence is key to the Dorsey playbook. Among the many lessons he learned while confronting crises and earning his bosses positive press, one was to consistently reinforce a key message to the public: Progress is not only on the horizon—it is already being made.

Since his May appointment as supervisor for San Francisco’s Sixth District, which includes the South of Market area, the Design District, Rincon Hill, Mission Bay and Treasure Island, Dorsey’s insatiable work ethic has been on full display. He has held numerous press events with Mayor London Breed, District Attorney Brooke Jenkins and Police Chief Bill Scott. This foursome have linked arms since the recall of progressive prosecutor Chesa Boudin and vowed that, together, they are addressing the drug crisis and quality-of-life concerns plaguing San Francisco’s Downtown core.

In a savvy move to corral earned media ahead of the election next month, Dorsey released a 27-page resolution—replete with footnotes—on how he hopes to pool the city’s immense resources and finally address the city’s drug epidemic. The chances of his plan coming to fruition are likely slimmer than the documents on which they are written, but Dorsey received credit in most corners of City Hall for his collegiality in attempting to bring commissions and departments together.

And while he claims a run for office higher than his current perch is not in the cards, the longtime political puppetmaster’s ambitions are starting to take form.

The Salesman

It feels a bit on the nose for an interview in Dorsey’s Mission Street campaign headquarters, which he shares with DA Jenkins, to take place in an interrogation room, but here we are. Across a sparse table, the 57-year-old former police spokesman is sitting under two yellow lamps descending from the ceiling and telling his life story, from coming to San Francisco in 1990 to work on then-DA Arlo Smith’s campaign for state attorney general to massaging all manner of messages coming out of City Hall.

This includes going after Juul when the e-cigarette company was found to be targeting minors in its marketing, fighting for LGBTQ+ rights when the city began issuing same-sex marriage licenses and, most recently, shielding the police department and its brass from political blowback amid a public furor over crime.

“I’m a believer in reform, and I do think that the Chief [Bill Scott] has been doing great work,” Dorsey said of his former boss. “That doesn’t mean that I’m being a copagandist. I do think I wanted to be an evangelist for reform.”

Since this spring, Dorsey has traded ghost-written bylines for stump speeches in which he shakes a thumb-extended fist and quotes the late gay rights icon Harvey Milk. He grins and he talks about hope in a city going through the throes of addiction and homelessness. A Dorsey speech also rarely omits his own struggles with addiction as an earnest example of why San Francisco should buy what he’s selling. In a debate held this month at The Standard’s offices, he called this work “the obligation of my survival.”

“He’s got a lot of ideas, and he loves talking about them,” said Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, who is a longtime friend and supporter of Dorsey’s. “He thinks a lot about framing and how to solve a problem. And he will talk your ear off about it. As a politician, he has a very Irish Catholic, Massachusetts-ey style.”

His critics—and there are more than a few in the more progressive wing of the city’s Democratic Party—would argue that Dorsey’s goals aren’t the issue, but rather it’s the paradox in how he merges harm reduction and tough-on-crime talk.

Peter Calloway, a public defender in the city who has accused Dorsey and Jenkins’ rhetoric as a futile attempt to incarcerate San Francisco out of its problems, said he and others have had trouble pinning the supervisor down.

“I think his messaging is effective,” said Calloway, who lives in the Tenderloin, which up until the spring redistricting process was part of District 6. “But to what end?”

John Crew, an attorney and police reformer who died earlier this month, told The Standard in an interview over the summer that Dorsey’s impact on the police department was substantial and oftentimes overtly political.

“It’s important for police officers to understand their obligation to tell the truth,” Crew said, whether it be writing crime reports or testifying in court. “When you lie on every press release, when you completely spin and misuse the use-of-force data—when officers see the department operate in such a blatantly political fashion, it creates an environment that is very dangerous.”

The Addict

The pressure of stepping out of the staffing shadows and into the limelight as an elected official in San Francisco is a risky proposition for Dorsey.

David Chiu, the current city attorney and a former supervisor, once compared the city’s politics to “a knife fight in a phone booth.” (opens in new tab) Dorsey touts his experience with addiction—he said he first became sober Dec. 2, 1992—as a trait that makes him uniquely qualified to understand and confront a drug crisis that claimed the lives of more than 1,300 people in the city during 2020 and 2021.

While out campaigning ahead of the Nov. 8 election, which is now underway thanks to mail-in ballots, Dorsey has been candid about his recent relapses. He went to rehab in 2018 and stumbled again in 2020—the latter being the same year he took a job as the director of strategic communications for the police department.

Dorsey said he took crystal meth, GHB “and party drugs like ecstasy or MDMA” during his 2018 relapse.

“I’m a gay man, and if the right hot guy asks if I want to party, you know, if I’m not doing my part to work a good program, I can be vulnerable to some bad decisions,” he said.

In 2020, Dorsey said, he fell off the wagon again as the pandemic lockdown took hold and he realized in a moment of weakness that he had GHB in his apartment.

“In some ways, I think especially doing politics, I don’t know that I can even competently do this if I didn’t have a program,” Dorsey said. “Today, I’m in a place where I’m so grateful for the program I have that I’m grateful for the disease that got me there. It helps me have perspective. It keeps me humble. It keeps me service-oriented.”

Mayor Breed said she appointed Dorsey over his election challenger Honey Mahogany, a social worker and trans woman, after residents told her their top concern is crime.

“Matt rose above the rest of the people that I talked to, in terms of his strong commitment to be very assertive on how he works on public safety for the people of that district,” Breed said. “I like that he is doing exactly what he said he was going to do.”

Dorsey actively sought the mayor’s appointment and quickly supported her proposal to substantially increase spending and officers’ access to surveillance tools. But while some would call this a sign of consistency or reliability, Dorsey’s opponents would call it craven obedience.

“Matt Dorsey has always been accountable to somebody else, whether it be the police or, in this case, the mayor,” Mahogany said.

Mayor Breed rejected that premise.

“To imply that Matt is not independent is really disrespectful and wrong in light of everything that he’s done in light of his service to the city,” she said. “That’s ridiculous.”

The Survivor

Matt Dorsey is an addict, a brother and a godfather, a gay man and survivor of HIV, a lover of One Direction and Bruce Springsteen, a marathon runner, a dinner party raconteur, and also a rare Irish Catholic who isn’t ridden with guilt.

But in nearly a dozen interviews with people who have worked with and against Dorsey, one description repeatedly emerges. He has the rarest of reputations at San Francisco City Hall: He’s a nice guy.

Keeping up a facade of friendliness over the course of two decades is nearly impossible in a building that oozes toxicity. But there is a near consensus that Dorsey is a genuinely good person who works at a maniacal pace and suffers from moments of weakness. His generosity to others has often been returned during these struggles.

Aside from losing both of his parents, one of his lowest moments came in 2003, when he tested positive for HIV.

“I was surprised by the result,” Dorsey said. “I actually thought the test was false, that there must have been a false-negative previously, because there was one incident where something unsafe happened. […] What I realized, years later, was that the likelihood of a false negative is very, very small and what likely happened was condom failure, which is why PrEP (opens in new tab) is so important.”

He tried to put on a brave face when telling friends and family, but it wasn’t until he went to lunch with Jeff Sheehy, a former District 8 supervisor who is gay and also talks openly about his own HIV diagnosis, that he found some solace in knowing he would be all right.

“Jeff Sheehy sat me down and said, ‘Get this doctor, get this insurance, do this, do this, do this. You’re going to be OK,’” Dorsey said. “I will always remember Jeff Sheehy’s friendship. So, that matters—and still matters a lot to me. And in some ways it was a wake up call. Right after that I started running marathons.”

Dorsey, who has been in a relationship with his partner for a year, declined to go into the details of his recovery program, but a key part of his personality is to do everything big. He nerds out on research, and he has traded the wild days for hard times running the hills of San Francisco.

“I love running because it makes me love my city,” he said. “Just being able to go out on a long run for 16 miles, I’m never going to win one of these [races]. But endurance running is kind of nice for me.”

Dave Burke, a San Francisco police liaison (opens in new tab) and Dorsey’s closest friend going back to their time as roommates in Boston after college, was with Dorsey during the hard times and has been inspired to see him bounce back.

“He’s the kind of guy who dives in on everything,” Burke said. “He’s ridiculously thoughtful, both on a personal and professional level.”

Perhaps one of the biggest tests of character and professionalism, he added, came in 2020 when Dorsey admitted to Chief Scott he had broken the law and relapsed with a Schedule I controlled substance.

“I told Matt, my biggest fear is that I’m going to go down to the [Medical Examiner’s] Office and they’re going to pull my friend out of a god-damned drawer,” Burke said. “He felt it was the only way to keep his job. I give him credit for having the balls to do that. And I give Chief Scott the credit for seeing that in him.”

Chief Scott declined requests to be interviewed for this story.

Not long after his supervisor appointment in May, Dorsey attended a recovery event and was approached by Afshin Palomo, a 33-year-old city resident who has also struggled with addiction and was inspired by Dorsey’s story.

“We just ended up chopping it up about recovery in general, and I mentioned to him that I had been loyal to myself in making a step to change my life,” Palomo said. “It was kind of spur of the moment and I asked him, ‘Hey, are you interested in picking up a sponsee?’ I had no idea about anything that had to do with who he was or what he was up to in life.”

Dorsey was surprised by the request, saying his instinct was to decline.

“I was about to say, ‘I can’t. I’ve got to be a supervisor. I got to get the campaign off,’” Dorsey said. “But the thing is, as if telepathically, my sponsor connected to my ear and said, ‘What’s more important than this?’ And I looked at him and I said, ‘Alright.’”

Over the last three months, Dorsey and Palomo have been texting in addition to talking on the phone in weekly scheduled calls. It’s a noble thing to do, and yet, the problems Dorsey is tasked with confronting involve helping thousands more people who are suffering on the streets in the grip of addiction.

“My time as a supervisor,” he said, “if I get it right and if there is a superpower I bring to this, it’s that there’s never going to come a day that I walk into City Hall without knowing that I’m an addict.”

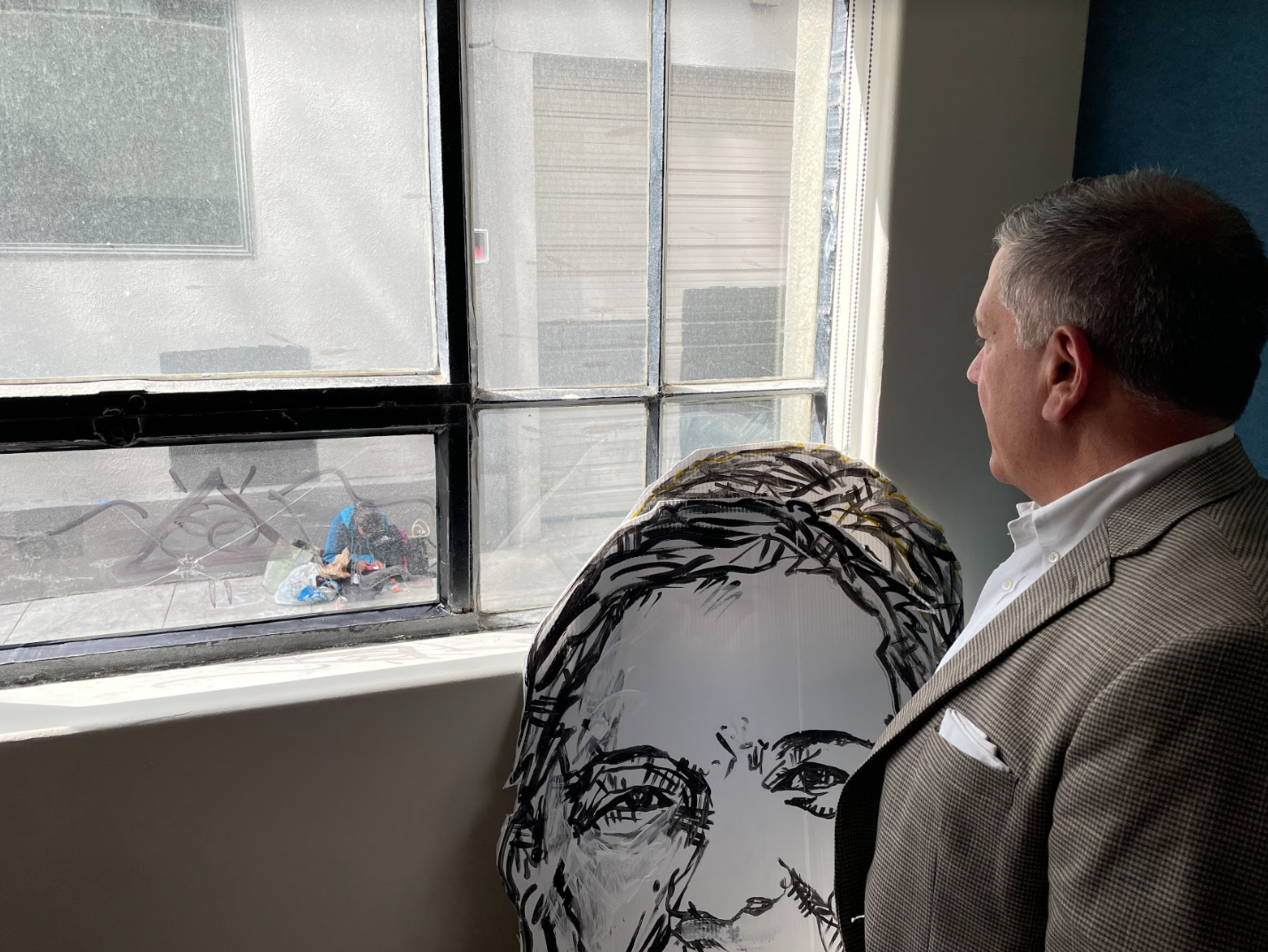

Following an interview at his campaign headquarters, Dorsey looked over his shoulder to see a hole in the window overlooking the seedy alley that is Minna Street. He got up and inspected it, only to then see a woman through the glass. She sat on the ground, belongings strewn around her, holding a glass pipe and raising a small torch. At the end of the alley, a police SUV sat idle at the corner. Dorsey watched the woman smoke her drugs.