In the run-up to his reelection as governor of California, Gavin Newsom swore up and down that he had no interest in running for president of the United States.

We could take him at his word. We could be wary of presuming what lurks in the mind of a slick career politician. Or, we could choose to live in reality.

At this point, it doesn’t seem to be a question of whether Newsom will run for president—it’s a question of when. Fears of a “red tsunami” in which Democrats would be bounced out of Congress in Tuesday’s election were greatly overblown, giving President Biden some cover. He said on Wednesday he expects to make a decision on running in 2024 early next year (opens in new tab). But speculation on Newsom’s future is already well underway.

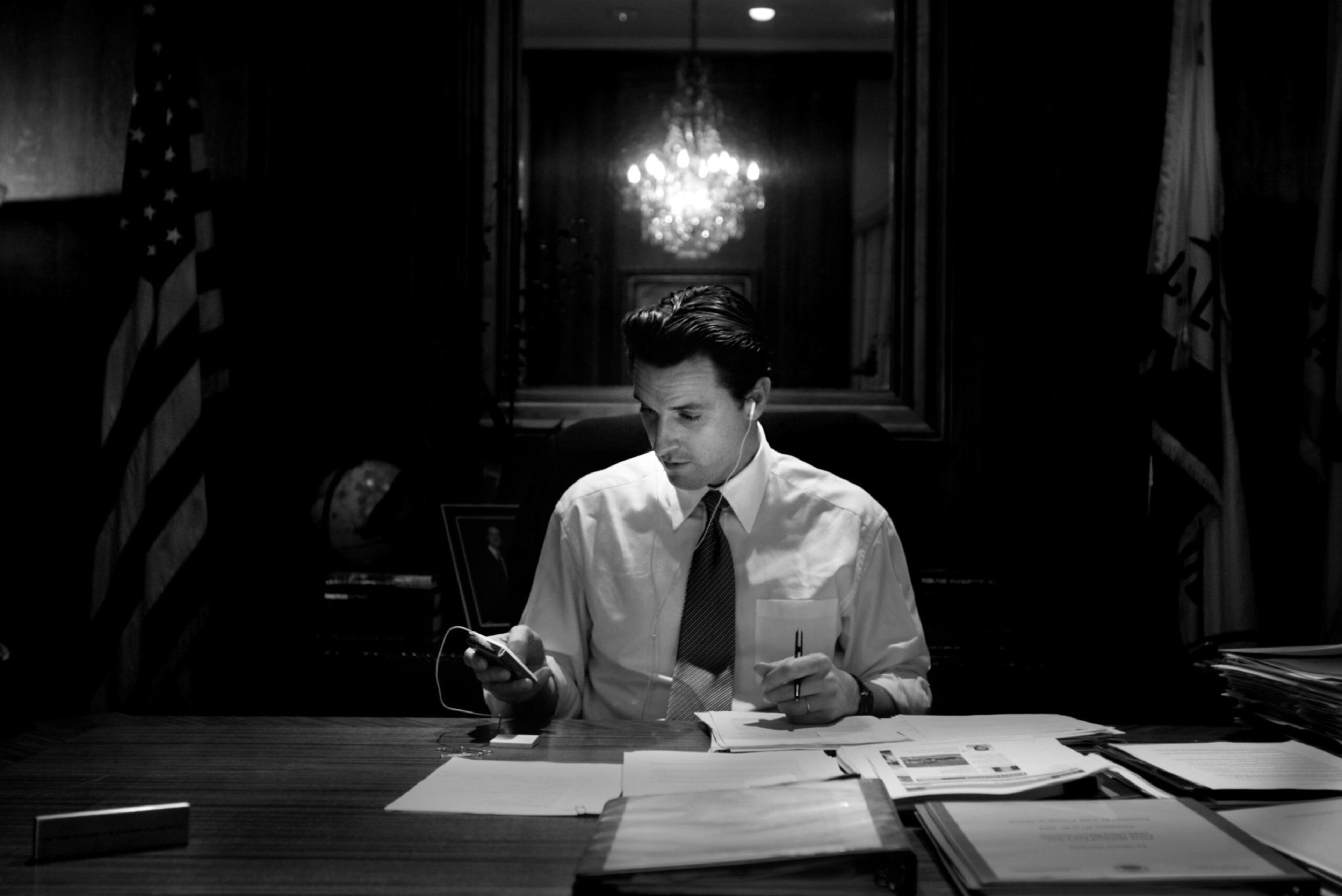

To better understand what kind of presidential candidate and—gulp—actual president Newsom could be in the future, The Standard interviewed almost a dozen people who have worked with and against him during his time as mayor of San Francisco and governor of California. While the odds of Newsom actually winning a presidential election might seem slim at the moment, the odds of him running—either in 2024 or 2028—most certainly are not.

Newsom’s office did not respond to an interview request or emailed questions for comment for this story, but conversations with campaign consultants, current and former elected officials, and City Hall and state Capitol insiders—most of whom agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity—reveal Newsom to be many things:

A dogged student of the game whose dyslexia gave him fits in school but made him a savant at retaining policy and reciting stats. An aloof colleague who stiff-arms anything beyond surface-level relationships. An orator prone to dropping $10 words when a dime would do. And a calculated gambler who reads the political tea leaves better than most.

If there is a consensus to be found on Newsom, it’s that no one seems to know the real Newsom. His true character and motivations remain distant, apart, enveloped in a fog that traces back to San Francisco.

A Vision Without Direction

It’s not difficult to see how a handsome 36-year-old mayor of San Francisco—the youngest person to hold the office going back a century—would have an ego.

After winning his first mayor’s race in 2003, Newsom handed out copies of Malcolm Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point (opens in new tab) to some of his supporters—along with a note telling them to go through his press department if they wanted an audience in the future. The distribution of pseudoscience reading material accompanied by passive-aggressive notes was a harbinger of the image-obsessed mayor Newsom would soon become.

Newsom cultivated his brand around being “aspirational” and always in pursuit of a “big, hairy audacious goal.” (opens in new tab) But this bombast—along with broken political promises and 11th-hour budget cuts—often rubbed city departments and progressive colleagues on the Board of Supervisors the wrong way.

“It’s great to have a vision and express that vision, but at the end of the day, you gotta talk to people who work for you,” said Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who was serving his first stint on the board when he started clashing with Newsom. “And he didn’t do the latter part of that.”

Mayor Willie Brown, who appointed Newsom to the Parking and Traffic Commission in 1996 and then elevated him to supervisor a year later, had an even more blunt assessment of Newsom’s struggles to build consensus, and how that might affect his ability to work with Congress.

“Gavin doesn’t exactly cultivate friendships,” he said.

In his first year as mayor, Newsom made a calculated play to allow same-sex marriages at City Hall while it was still illegal under state law. Many who worked with the straight, white mayor were concerned the move would hurt him politically, not to mention risk progress for the equality movement. Others in the city considered Newsom’s actions craven.

“I really think he stood on the shoulders of a lot of people who had suffered and died,” Tom Ammiano, an openly gay former supervisor and assemblyman, told the Los Angeles Times (opens in new tab). “It really wasn’t all about him, but he made it all about him.”

Regardless, Newsom cemented his image as an LGBTQ+ ally. The cliff notes of that moment would play well nationally on the heels of the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade, with LGBTQ+ rights seemingly next on the chopping block.

A common criticism of Newsom’s time as mayor was his lack of attention span or the desire to focus on the basic tasks of governing. He absorbed input from staff but preferred to go big, such as when he floated an idea to install turbines under the Golden Gate Bridge as a city-controlled energy source. A study found it would produce just two megawatts of power—enough to keep the lights on in fewer than 2,000 homes—but Newsom vowed: “I am going to find a way to make it happen.”

He didn’t make it happen.

Undeterred, Newsom set out on a path to brand himself as a leader in promoting new energy sources, a popular rallying cry in the face of climate change. During a climate change event last month atop the Presidio Tunnel Tops park, Newsom effectively gave a stump speech in which he slammed Vladimir Putin, “petro-dictators” and Fox News’ Tucker Carlson.

In 2008, Newsom rolled out Healthy San Francisco, a public healthcare plan that went a long way toward helping tens of thousands of the city’s poorest residents get free medical treatment. He has advocated in the past for a single-payer healthcare system—something impossible to do at a state level—and he could certainly make this part of a presidential platform.

But the boldest policy Newsom championed in San Francisco started during his time as a supervisor in 2002. It would not only propel him to the Mayor’s Office but become his signature achievement as he sought a statewide office.

Newsom and Trent Rhorer, executive director of the city’s Human Services Agency, designed the Care Not Cash program to reduce direct cash payments to low-income and homeless residents and instead require these individuals to seek out city-provided shelter. As a result, people who qualified would receive greatly reduced monthly stipends, and the city would save millions.

Supervisors pushed back on the plan and homeless advocates slammed it as a shell game that dispassionately moved around people in need of housing. Peskin said the supervisors were about to pass Care Not Cash, but Newsom pulled it before supervisors could cast a vote because he wanted the name recognition and credit by taking the measure to the ballot himself.

Voters passed Care Not Cash, aka Proposition N, with 60% in favor, and Newsom spent the next year going to roughly 1,000 events—almost three a day—as he ran for mayor, according to his then-campaign manager, Jim Ross.

An audit found the Care Not Cash program turned out to be a success in getting thousands of people into services and saving the city money. However, many San Franciscans were under the impression it would help solve homelessness. This was certainly not the case.

In 2005, a year after Newsom took over as mayor, the city’s annual homelessness count found 2,655 people were living on city streets (opens in new tab). That number is now estimated at more than 7,700.

“He got us all to sign on to Care Not Cash,” Brown said. “And then he got out of town before the debt became due.”

Sex and the City

Newsom has many of the signature traits of a leading statesman, but over time, they can become off-putting.

A polling expert told The Standard that Republicans would love to see Newsom run for president in 2024 not only because of San Francisco and California’s national reputation as a hellscape beyond repair (thanks, Fox News!), but also because Newsom’s approval ratings go down dramatically after a polished first impression.

He has the statistical recall of a card counter, but too often the laundry list of numbers begins to feel like navel-gazing. He speaks in a chewed gravel voice (opens in new tab) that suggests he might once have been a pack-a-day smoker, but it’s more likely he’s just channeling his inner Batman (opens in new tab). And then there’s the rakish good looks and angular suits of a Patrick Bateman (opens in new tab) clone.

In 2001, while still on the Board of Supervisors, Newsom married Kimberly Guilfoyle—then a prosecutor in the District Attorney’s Office. Three years later, the gods blessed the internet for eternity with a Harper’s Bazaar photo shoot in which the couple finger-locked on an opulent rug in the Getty mansion.

The marriage would crumble after four years, setting off what could be called Newsom’s wild days.

“Mayor McHottie” made waves when he started dating a 19-year-old woman (opens in new tab), who was half his age. But the low point in Newsom’s personal and professional life came in 2007 when word leaked of an affair involving Ruby Rippey-Tourk, the wife of Newsom’s deputy chief of staff, Alex Tourk.

“I can tell you,” said Joseph Cotchett, an attorney and longtime friend of the Newsom family, “it’s a piece of his life that he’d like to throw away.”

The mayor immediately confessed to the affair to a room full of reporters before checking into rehab for alcohol. It’s unclear if alcohol was just a convenient excuse for the sex scandal, as Newsom has acknowledged he still drinks in moderation.

Tourk declined to comment for this story.

The mayor’s world became decidedly more insular after the affair, and his critics felt more emboldened to slam him in the press. Meanwhile, Newsom’s relationship with the media deteriorated to the point that he stormed out of an interview after he took a secret trip to Hawaii.

Newsom no longer sees much utility in working with the press except on his terms. His relationship with the media—much like with his colleagues—is transactional, and he prefers to only grant access to national outlets. Anyone expecting him to consistently face the music in the White House briefing room is kidding themselves.

After the affair came to light, many of Newsom’s allies in San Francisco—people who also counted Tourk as a friend—were furious, but the people of San Francisco seemed to care little. Newsom was reelected in late 2007 with more than 73% of the vote.

Growing Pains

Newsom’s ascension of the political totem pole hit a rare snag in 2009 when it became obvious Jerry Brown intended to reclaim his role as governor.

The ambitious mayor of the nation’s most progressive city—despite getting remarried in 2008 to actress and documentary filmmaker Jennifer Siebel—still had an image problem after the affair. And the institutional powers were aligning with Jerry Brown, a much safer bet.

Newsom bowed out of the race and easily secured the position of lieutenant governor. He resented the job, calling it dull because it has “no real authority and no real portfolio” (opens in new tab) beyond serving in the governor’s stead when out of state.

But in many ways, this time out of the spotlight served Newsom well.

During two terms as lieutenant governor, he built new bridges at the Capitol to replace the ones he burned on his way out of San Francisco. He had time to meet with tech entrepreneurs, pick their brains and then put forward bold policy proposals—proposals, it’s worth noting, that went mostly ignored by Gov. Brown.

Meanwhile, Newsom and his wife grew their family to four children. He hit the books and wrote one of his own, “Citizenville: How to Take the Town Square Digital and Reinvent Government. (opens in new tab)” The call-to-action tome was lauded by some while it elicited eye rolls from others. Regardless, the book certainly spoke to the ambition of someone preparing for his next job.

“I’m genuine when I say: A wife and kids have matured that guy so much. He’s completely different,” said a City Hall source. “The emotional maturity is so much more than what it was when he was mayor.”

By the end of these two terms, voters were comfortable promoting Newsom to governor of the most populous state in the union—and by extension, making him CEO of the fifth largest economy in the world.

Man of the House

Newsom spent his first year in office focusing on core issues that resonate with California’s Democratic base: funding early childhood education (opens in new tab) and addressing homelessness. He didn’t make much, if any, progress on his goal of building 3.5 million homes in the state by 2025 (opens in new tab), but he certainly signed plenty of legislation and said the right things. The pandemic interrupted much of this work.

But of the many actions Newsom has taken as governor this year, the one that signaled his greatest intent to run for president came from something he didn’t do.

In August, Newsom vetoed SB 57, a bill from state Sen. Scott Wiener that would have created a pilot program for safe-consumption sites in Los Angeles, Oakland and San Francisco. Newsom had previously expressed support for the idea, which studies have shown can save lives, but he cited concerns about an unlimited number of facilities popping up.

Political observers knew better—Republicans would have used the legislation as red meat to accuse Newsom of essentially legalizing drug dens across California.

Jeannette Zanipatin, California’s director for the Drug Policy Alliance, told Politico (opens in new tab) after the veto that Newsom’s decision “definitely signals that he was concerned about how this might play out in the media, as well as the political arena.”

Any presidential campaign of Newsom’s is sure to be met with attack ads showing the squalor in San Francisco’s Tenderloin and Los Angeles’ Skid Row, both of which are not only dealing with a drug overdose crisis but also rampant homelessness.

But many say that to his credit, Newsom creatively responded during the first year of the pandemic with two projects to help the homeless: Roomkey (opens in new tab) and Homekey (opens in new tab). The former took advantage of suddenly empty hotels by using federal funds to usher in people who had nowhere to go and faced a severe risk of infection, while the latter allowed the state to buy and convert hotels and vacant apartments into permanent housing.

None of this, of course, has solved the state’s housing crisis—and the high cost of living, rampant homelessness, and residents and businesses fleeing for other states will be politically weaponized for any California candidate who runs for president.

“The one thing he hasn’t focused on and came kind of Johnny-come-lately to is the whole housing issue,” a political consultant said. “To me, that should have been his No. 1 focus from Day One in office.”

Gavin Goes to Dinner

Despite his inability to connect with colleagues, Newsom has always looked comfortable on camera. Throughout the first year of the pandemic, he often joined health officials in delivering daily updates. The reports were lengthy and full of Newsomisms—recalling for many in San Francisco the infamous State of the City speech Newsom gave in 2008 (opens in new tab), which ran more than seven hours and was split into 10 webisodes on YouTube.

“To give him some credit, he’s willing to push the boundaries,” a political consultant said. “But I think five minutes after he starts talking, you’re like, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’ He uses 10 words when he could use one. As president, you’re speaking in sound bites and snippets.”

Near the end of 2020, Californians were antsy but buoyed by talk of a vaccine being on the way. And then Newsom went to dinner.

Newsom was photographed sitting maskless in a group at the swank French Laundry restaurant, giving talking heads, quarantining conservatives and Republican governors all ammunition they needed to deride Newsom as a coastal elite.

Republicans across the state—many of whom were already upset about mask and vaccination requirements—started calling for Newsom’s head, and tens of millions of dollars were raised to collect recall petition signatures.

But unlike the successful recall of California Gov. Gray Davis in 2003, Newsom didn’t have a global superstar like Arnold Schwarzenegger running to give people an attractive option as a replacement. By the time voters went to the polls in September 2021, many of the pandemic-era restrictions on life had been lifted. Despite spending more than $200 million on the recall election, the state was flush with cash thanks to the tech sector’s ridiculous growth during the pandemic.

Newsom and his supporters raised more than $70 million to fight the recall, and more than $20 million of this money has been sitting in a political action committee Newsom now controls after handily defeating the recall.

Perhaps the most beneficial aspect of the recall for Newsom is that it gave him the kind of reps only a seasoned presidential candidate gains from hitting the campaign trail. Newsom learned how to frame his messaging against a Trump-aligned GOP and started to see the bigger picture.

“That recall made Gavin understand what the world is all about,” Cotchett said. “First, it scared the shit out of him, as it would any politician. But then it gave him a voice statewide, which he didn’t have. He went from San Francisco to Sacramento, and the state is a lot bigger than San Francisco or Sacramento. That recall allowed him to touch 40 million people.”

The Fight To Come

A fair number of political oracles believe President Joe Biden will announce he is stepping down after one term after Labor Day next year. If true, this would set off a cannibalistic scrum in the Democratic Party.

The contenders to get the nomination—or at least the men and women who view themselves as such—would be more than a few. How a liberal governor from California would be received by middle-American voters is a reasonable question to ask. After that, one could ask how well he would work with Congress.

“Look at his history working with 11 supervisors,” a City Hall source said. “Now, all of a sudden, he’s going to work with 535 members of Congress?”

However, even some of Newsom’s fiercest opponents during his days in San Francisco said they have seen a change in the dozen-plus years since he served as mayor. Most notably, he has overseen the fifth-largest economy in the world, which some economists expect to surpass Germany next year to move into fourth place.

“Gavin has grown as an elected official in just unbelievable ways,” said Ross Mirkarimi, a progressive former supervisor and sheriff in San Francisco. “I don’t care if you’re Republican, Democrat or independent—Gavin Newsom is one of the best elected officials in this country right now. And I don’t say that lightly, because we did come from opposing political camps.”

The lure of running against someone like Trump or Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis would certainly be attractive to Newsom—and vice versa!—but he could be dissuaded from joining the race for two notable reasons.

First, Newsom’s children are all still quite young, and putting them in the spotlight of a presidential race—and potentially being under the global microscope of living in the White House—would be difficult.

The second factor is who Newsom would have to defeat to secure the nomination. During his run for mayor, Newsom grew close with Kamala Harris, who at that time was running to become the city’s district attorney. If anyone could be described as a friend of Newsom’s in the weird world of politics, it’s Harris. Their donor base also has a huge overlap in contributors, with one campaign expert suggesting it’s around 70%.

“I take him at his word when he says he’s not going to run,” said Jim Ross, who ran Newsom’s 2003 mayoral campaign. “He sees it as: ‘If Joe Biden doesn’t run, then Kamala Harris becomes the front-runner.’ It would be very challenging for him to run in a race where Kamala is on the ballot.”

Polling shows Harris’ disapproval ratings are off the charts (opens in new tab) for a vice president, with FiveThirtyEight finding an aggregate of polls puts the number above 50%. It’s conceivable that number could get even worse between now and 2024, which would likely make Newsom think hard about jumping into the race if Harris is not competitive.

Newsom could also choose to bide his time, serve out his term as governor, spend more time with his young children and launch an aggressive bid for 2028.

No matter what Newsom says about having no interest in running, the caveat is always that he’s making these statements now—at a moment when there is still a sitting president. He could have a much different answer if Biden were to take his bike and fall off into the sunset.