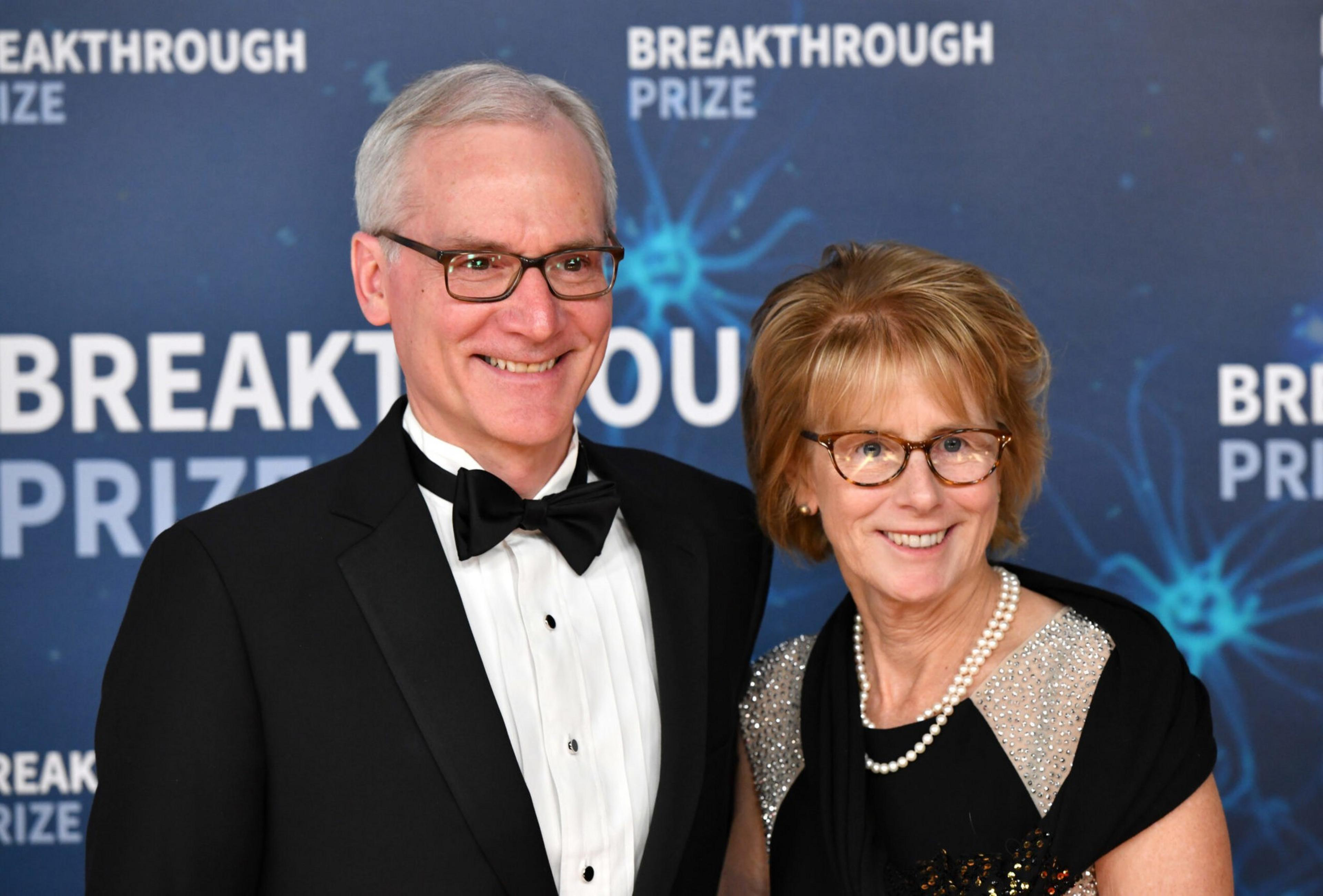

Stanford University administrators have publicly distanced themselves from a now-viral “harmful language” list published by the University’s IT department in December. In a statement sent to the Stanford community on Wednesday, President Marc Tessier-Lavigne wrote that the list of terms, which included commonly spoken phrases like “you guys” and “American,” did not reflect official university policy.

Stanford’s IT department launched the Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative (EHLI) (opens in new tab) in March 2022 (opens in new tab), sponsored by the university’s People of Color in Technology affinity group and other IT experts. The initiative was designed to educate only “members of the IT community” about potentially harmful language on Stanford’s websites and in code.

The list in question was included under Stanford’s EHLI site, but has now been taken down after university administrators said that the language list had “missed the mark.” The overall initiative is also being re-evaluated, Tessier-Lavigne wrote.

The harmful language list went viral in late December when major media outlets reported (opens in new tab) about the website, ridiculing some of the words as campus wokeness ran amok. While some observers praised the thoughtfulness behind the language initiative, others expressed concern (opens in new tab) that the website represented a banned words list, and that it could pose an affront to free speech.

“Many have expressed concern that the work of this group could be used to censor or cancel speech at Stanford,” Tessier-Lavigne wrote. “I want to assure you this is not the case. From the beginning of our time as Stanford leaders, [Provost Persis Drell] and I have vigorously affirmed the importance and centrality of academic freedom and the rights of voices from across the ideological and political spectrum to express their views at Stanford.”

Yet software engineers and tech ethics experts say that mitigating harmful language in code is a common practice at many tech companies, especially as language evolves to address systemic injustices and changing cultural norms.

The EHLI was created to address racist terms historically used in IT, according to a statement (opens in new tab) from Stanford Chief Information Officer Steve Gallagher. The initiative expanded its scope of “racist terminology in technology” to the broader title it now holds. Though the EHLI list included language deemed potentially harmful or offensive, it offered numerous alternatives (opens in new tab) for IT specialists to consider using instead.

Stanford isn’t the first to re-evaluate language used in its tech products—there’s precedent for language initiatives like this at tech companies across the country (opens in new tab), as occurred after the 2020 killing of George Floyd.

GitHub, for example, decided to change a repository’s default name (opens in new tab) from “master” to “main” (opens in new tab) in 2020, as phrases like “master bedroom” or “master” can carry the connotation of enslavement in America.

Stanford has been at the center of numerous campus free speech controversies over the past few years.

Since 2017, students have protested the invitation of speakers like anti-Muslim activist (opens in new tab) Robert Spencer (opens in new tab) and conservative political commentators Ben Shapiro (opens in new tab) and Dinesh D’Souza (opens in new tab). A media-free, invitation-only free speech event (opens in new tab)at the business school garnered criticism in October 2022, and the undergraduate newspaper is filled with student think pieces (opens in new tab) on First Amendment rights on campus.

And given Stanford’s many ties to the tech industry, many see what happens on the campus as a bellwether for the broader tech world—and they may be right.

Free speech debates swirl around social media conglomerates: Meta has faced consistent criticism (opens in new tab) for its handling of disinformation, and the recent release of the “Twitter Files” has stoked the flames for more heated discussions (opens in new tab) about social media and First Amendment rights.