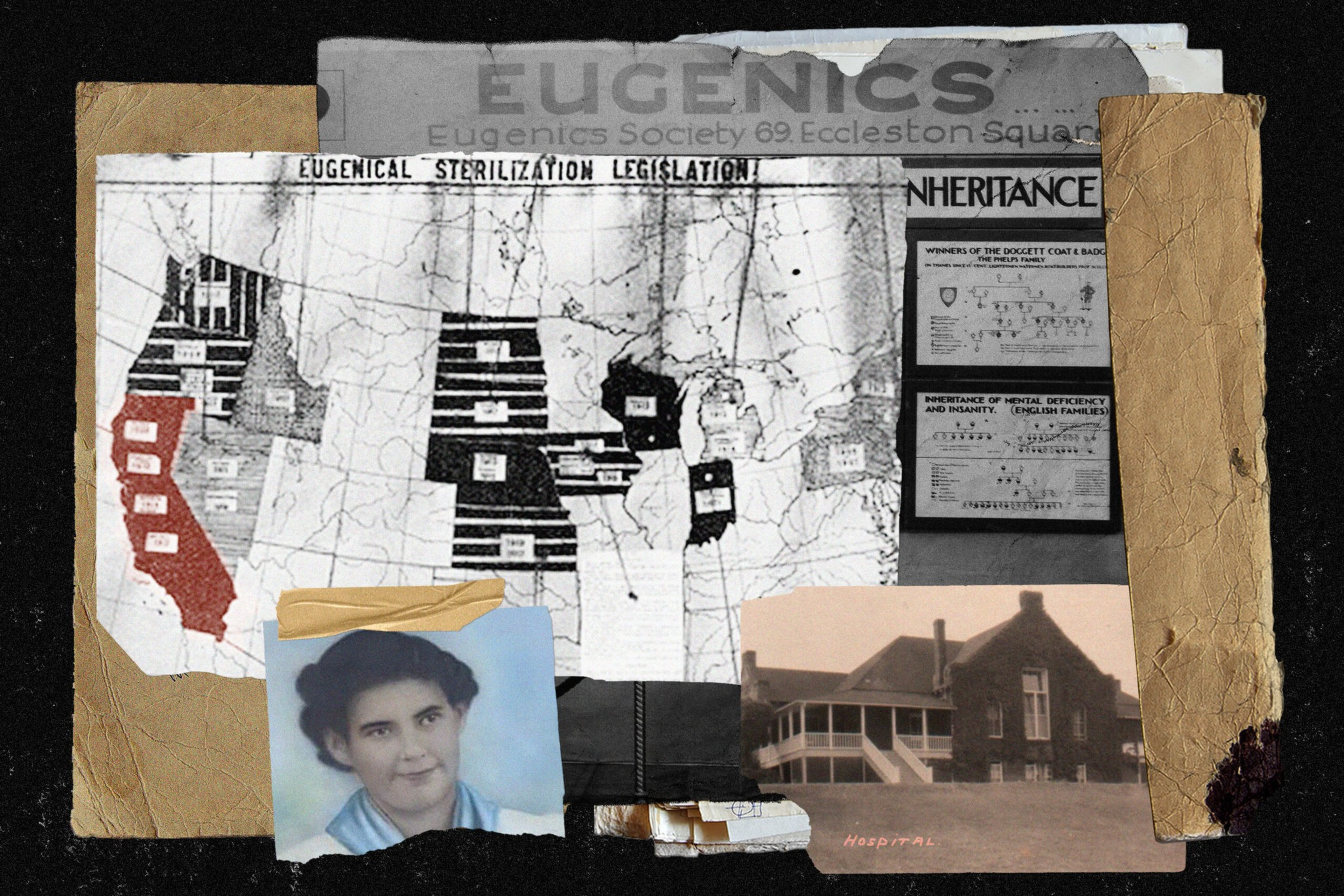

It’s easy to think of eugenics as something that happened far away from us, with ideals alien to our character. Yet Adolf Hitler himself studied—and was inspired by (opens in new tab)—American laws that prevented the birth of people “injurious to the racial stock.”

Eugenics—the desire to increase qualities deemed to be favorable within the gene pool, with sterilization as one of its primary tools—isn’t owned by Nazi Germany, and it hasn’t gone away.

Far from being a fringe movement, the eugenics movement cast its net over everyone from Planned Parenthood leader Margaret Sanger (opens in new tab) to Save the Redwoods League co-founder Madison Grant (opens in new tab). The movement’s creator, Francis Galton, was cousin to none other than Charles Darwin. The desire to improve the human race was tied up in what at the time seemed like a noble pursuit to make a better world, one that comes chillingly close to ideals we cherish today.

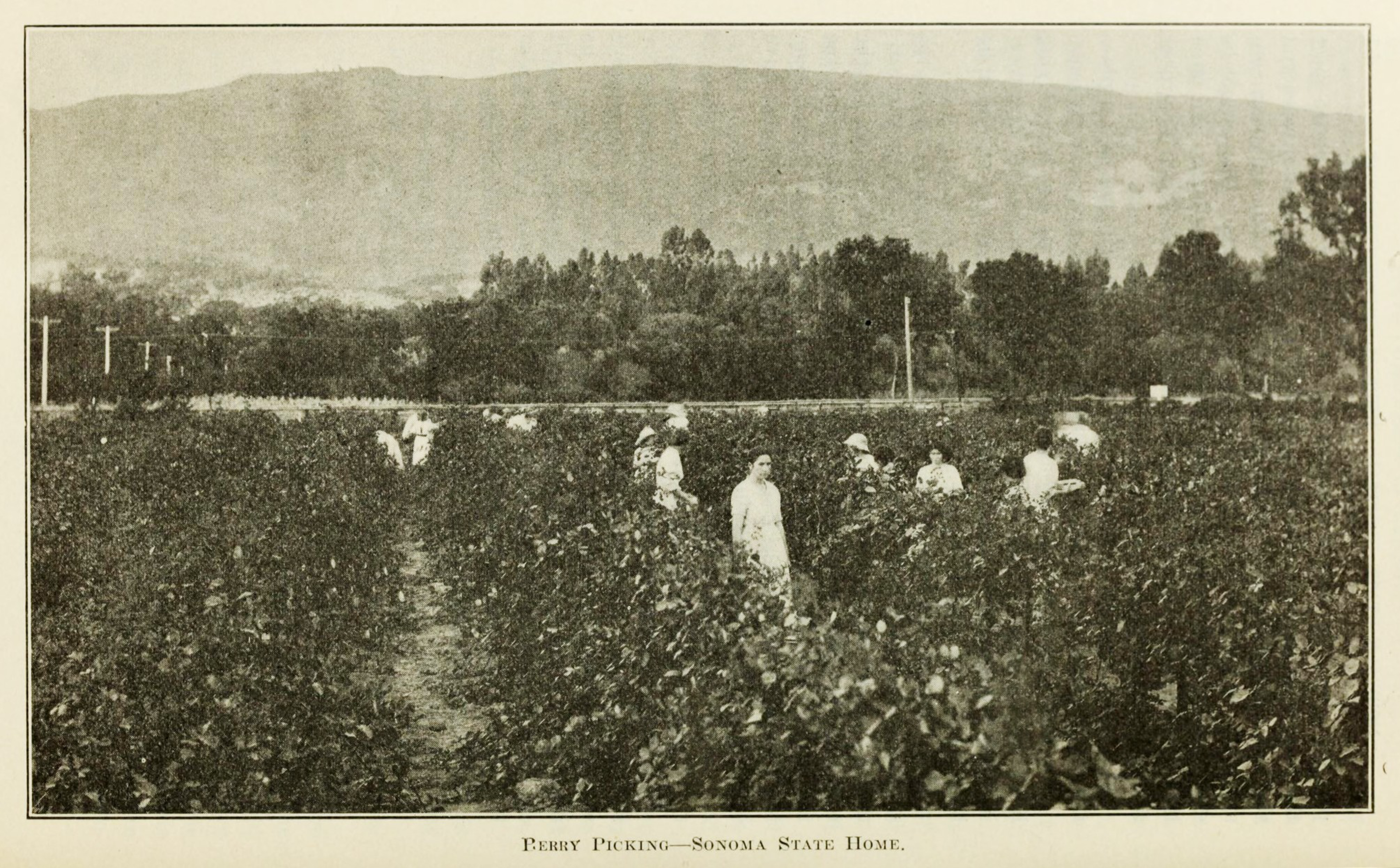

The arguable capital of the eugenics movement in the U.S. was even closer to home—in Northern California, where one third of America’s sterilizations occurred. And the Sonoma State Home, an institution opened in 1891 for the developmentally disabled, likely sterilized more people than any other institutional setting in the world (opens in new tab).

“It was a mostly male and white institution […] who thought they were taking on the biggest problems of the day in Northern California and in the West more generally,” said historian and author of Eugenic Nation Alexandra Minna Stern (opens in new tab).

These crimes were largely committed by a class of affluent do-gooders, who cloaked their pursuits in the language of science and human progress.

California is actively trying to find the survivors (opens in new tab) of this dark chapter of history so as to compensate them with up to $15,000 each in reparations under a state law that passed in 2021. But only 51 people have been approved for payments, even though there are as many as 600 alive today who would be eligible for the monies—and California has only one more year to find survivors until the $4.5 million program shuts down.

Yet, given the height of sterilization occurred in the 1930s, the vast majority of those impacted by California’s state-sanctioned eugenics program are already dead, their legacy a part of the fabric of our state.

“Eugenics history is a layer of the history of California,” Stern said.

While conducting her research, Stern discovered the sterilization records of over 20,000 people in a government office in Sacramento and calculated that nearly one-third of Puerto Rican women were sterilized by the U.S. government between 1933 and 1968.

Also troubling is that what made eugenics so appealing in its 1930s heyday overlaps with the core of Northern Californian ideals: our progressivism, our connection to nature, our frontier sensibility.

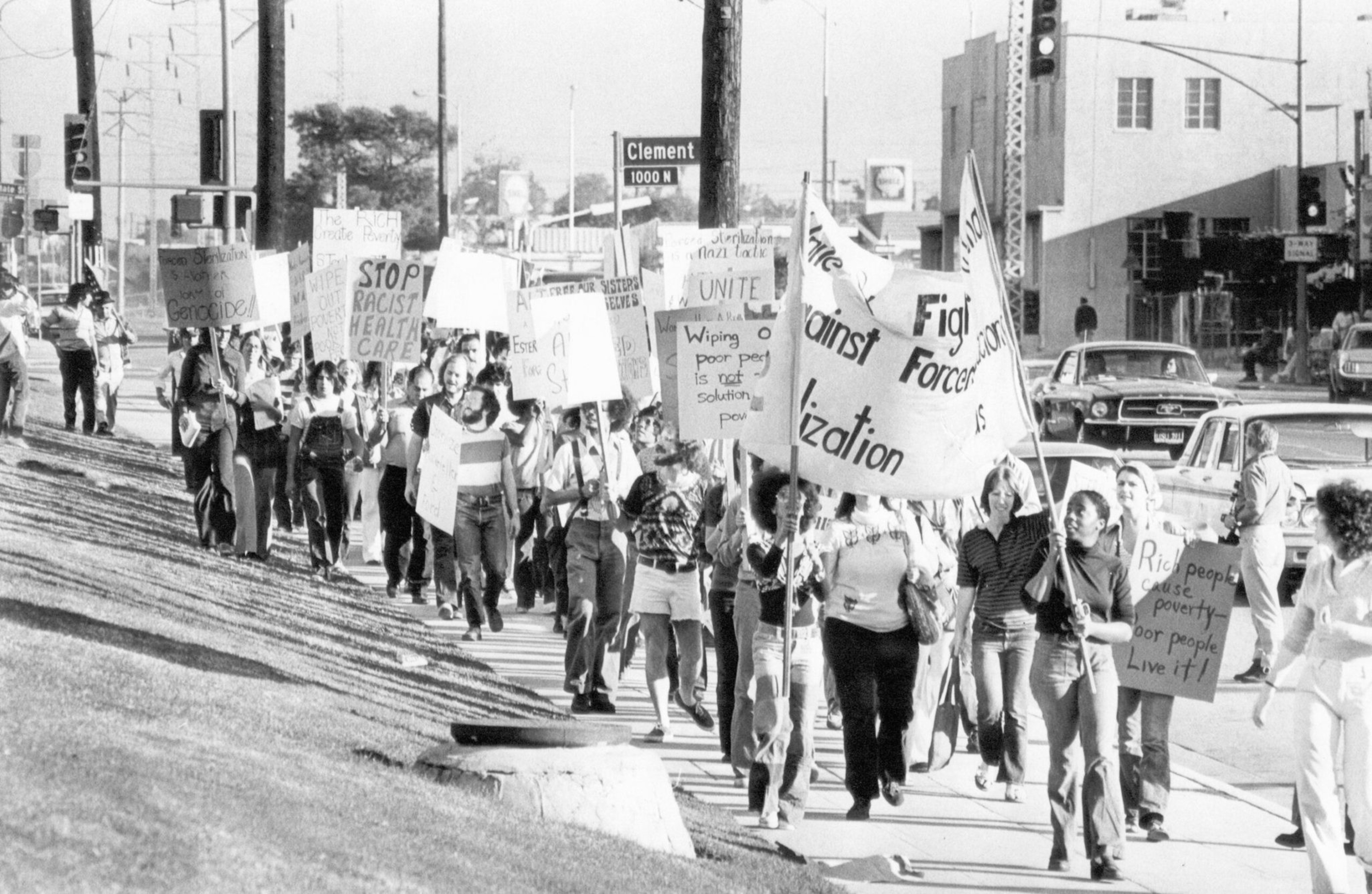

While eugenics is embedded in our history, it doesn’t belong to the past. The instincts that popularized the eugenics movement—a desire for purity, the impulse to control others’ bodies, the catchall categorizations—are gaining strength today.

Too Late for Too Many

Hayward native Barbara Swarr didn’t learn about her Aunt Rose until after she died, when her own mother’s death prompted her to learn more about her family. “I felt like an orphan,” she said.

Her digging led to a surprise when she learned that Rose—a tender, sweet girl who loved to play dolls with her cousins—had been sterilized.

“One day, one of my cousins said she was really friendly with the boys,” Swarr said. “And that’s one of the reasons why they did the sterilization, I’m sure, because they were scared she was going to get pregnant.”

Swarr’s aunt never made it home. Rose died on the operating table at the age of 16.

When Swarr had the opportunity to examine the paperwork that authorized Rose’s sterilization, she noticed names were spelled wrong and that the handwriting did not look like that of her uncle, who had supposedly taken her to the hospital.

“Somebody else did it all,” Swarr said.

Rose’s mother, Swarr’s grandmother, was dying of cancer at the time after having given birth to 13 children, only eight of whom had survived infancy. Family life was challenging.

“Immigrant life, it was really hard. They had no plumbing, no running water, only a well in the backyard,” Swarr said.

Swarr’s grandmother was particularly close with Rose, and soon after her daughter’s death she died of the stomach cancer that had been plaguing her.

“She died without her baby,” Swarr said. “It was really hard.”

While tragic, the story of Swarr’s Aunt Rose is not unique. Unsuspecting family members could easily be convinced by the government that sterilization was a responsible choice for a vast and puzzling variety of conditions: everything from depression to disabilities, tuberculosis to orphanhood—for both women and men.

“Because he is so young and I believe he will get well, I do not want to take the responsibility of giving signed permission,” reads the heartbreaking 1936 letter of a San Francisco parent protesting their child’s ordered sterilization, which Heather Dron, a research fellow with the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab (opens in new tab), uncovered in her research. “I realize you have the right to do what you think is best in the matter,” it continues.

Napa State Hospital went ahead with the sterilization procedure. The rationale on the paperwork: “mental disease which may have been inherited and is likely to be transmitted to descendants.”

More than 20,000 people were sterilized in California from 1909-52 in both public institutions and private hospitals, according to Dron. The categories for approval on sterilization contained opaque, dated categories like ”perversion” and “feeble-mindedness.”

Francis Galton—Charles Darwin’s cousin—first coined the term eugenics, which comes from the Greek word eugenes meaning “well-born,” in an 1883 book on the subject. The subsequent movement advocating its principles went mainstream, appearing everywhere from The Great Gatsby to college courses at Stanford and Yale. There were eugenics competitions, eugenics magazines—even eugenics cosmetics.

Control of other people’s bodies—and their reproductive options—could take many forms. Wives had to get the approval of their husbands to have hysterectomies as late as the 1960s, according to Dron.

Our state’s ambition to be on the forefront of cutting-edge technology may have been detrimental in this instance. “California went whole-hog early on,” said Dron. “This was progressive in a negative sense.”

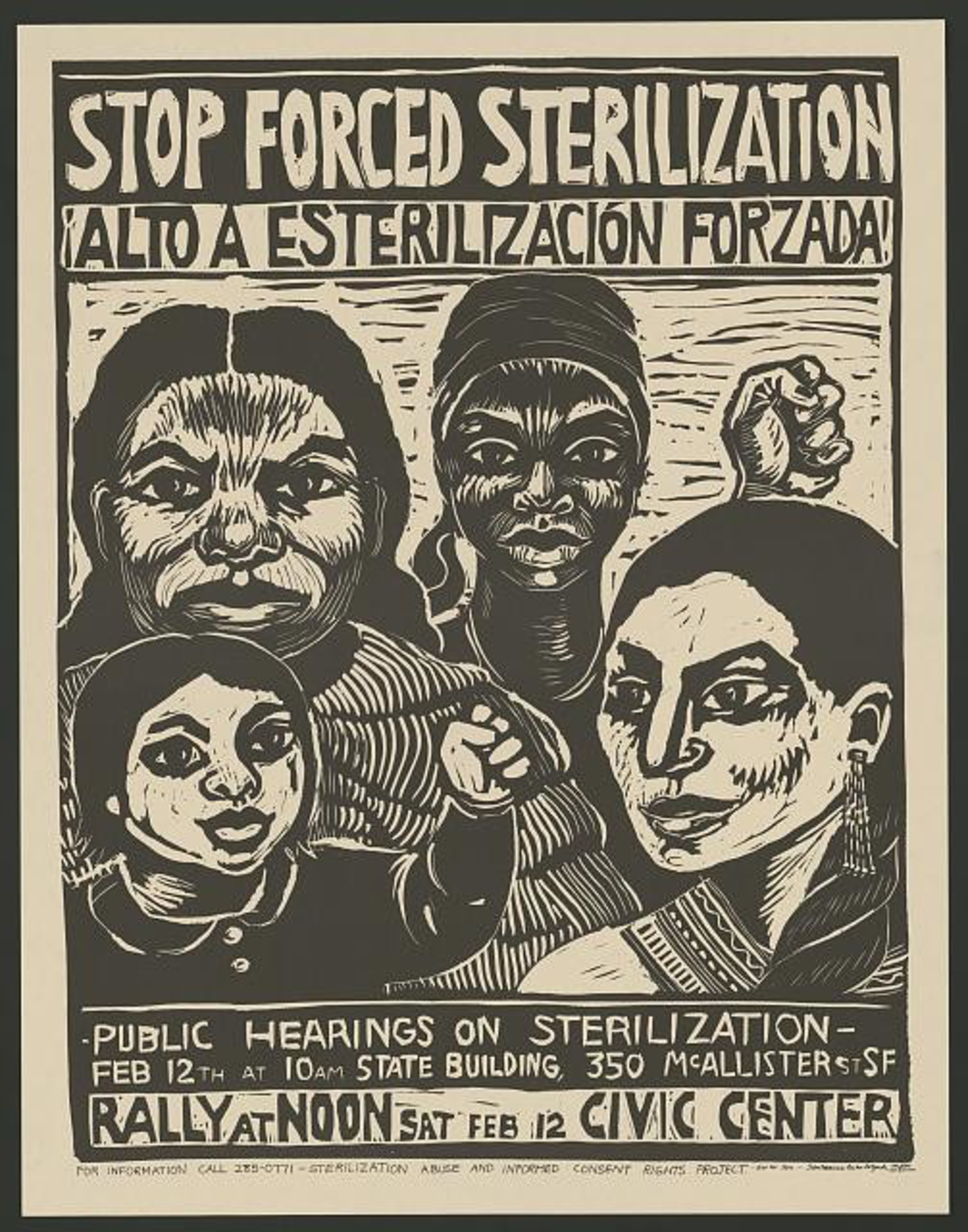

A Criminal Act

Even though California repealed its laws authorizing sterilization in 1979, the practice continued illegally, most often in prison settings. Many of the survivors eligible for California’s compensation law come from this demographic. Many did not realize they were sterilized until they tried to have children of their own.

“Different prison doctors seemed to think it was a good idea, and justified it on paper with physical issues, in particular for women,” said Diana Block from the California Coalition for Women Prisoners (opens in new tab). Block noted that her use of “women” is a catchall that includes trans and gender-nonconforming people.

Most prisoner sterilizations happened at two facilities: Valley State Prison for Women (which is no longer only for women) and the now-closed Central California Women’s Facility. Block estimates that as many as 1,200 prisoners were illegally sterilized.

The formerly incarcerated often do not spark much sympathy—especially from politicians, who are loath to be seen as being “soft on crime.” However, the suffering that has arisen in the wake of this policy has been so great that the government had no choice but to address the issue.

“The idea of compensating prisoners for harm has not been on anyone’s agenda,” Block said. “But people see how egregious this harm is.”

While Block champions the new law to compensate sterilization victims, she said that locating survivors has proven challenging.

“They can’t find them,” Block said. CCWP is holding a Feb. 2 event (opens in new tab) to draw attention to the subject and hopefully locate more survivors. Only 3 victims so far have been compensated under the law, according to Dron.

There have also been hiccups along the way. Insufficient outreach and a victim compensation board that’s not trained to look for this type of survivor, for example, have been roadblocks. A prisoner could have been convinced to be sterilized by a state agency that said it was the only way to cure their pain from whatever illness they were experiencing, further complicating the search for survivors.

“It’s better late than never,” Block said of the compensation law. “But it’s already too late for the people who were sterilized,” since they can’t have children.

The roots of forced sterilization’s connection to the criminal justice system stretches back to at least the 1930s. Many of the young girls sent to Sonoma for procedures went through the California juvenile court system, according to Stern.

“They would be brought in because of all these biases,” Stern said. “Class biases, racial biases and ableist biases.”

Having a boyfriend, being sexually abused or being labeled “promiscuous” could all lead to recommendations for a 16-year-old girl to be sterilized, according to Stern. Young people could have been sterilized at 15 or even younger in the 1940s, Dron said.

“San Francisco was a very important hub in channeling young people deemed unfit to state institutions,” Stern said. “There was almost a direct line.”

But while sterilization often impacted the vulnerable the most—the poor, those with mental health diagnoses, people of color and the incarcerated—even the wealthy and privileged could become convinced to recommend it for their own children (opens in new tab).

These Roots Go Deep

In Sonoma County, you can take money out of the Luther Burbank Savings and see a show at the Luther Burbank Center for the Arts. You can send your kids to Luther Burbank High School and play at Luther Burbank Park. The famed horticulturalist has been commemorated on stamps, baseball trading cards—even a stained glass window at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral.

Many would say that the inventor of the russet potato and the Santa Rosa plum deserves this kind of adoration. Yet what’s not included in these tributes is that even Burbank was pulled into the eugenics movement.

“He had a really romanticized vision of interracial mixing,” Stern said. “His idea was not unlike the Mexican idea of the Cosmic Race (opens in new tab).”

Burbank attempted to apply his learnings of agricultural cultivation to humans, writing the book The Training of the Human Plant.

“A little dose of this and a little dose of that would end up producing this superior racial hybrid,” Stern said. “He viewed California as the ideal laboratory for the creation of humans with this hybrid vigor.”

David Starr Jordan, head of the Committee on Eugenics and first president of Stanford University, made Burbank an honorary member of the association at the committee’s first meeting.

Yet Jane Smith, author of The Garden of Invention: Luther Burbank and the Breeding of Plants, underscores the “honorary” in the title. “He was not there at the meeting,” Smith said. “And Luther Burbank might have been friends with David Starr Jordan, but he was also friends with Helen Keller and the author of Autobiography of a Yogi, Paramahansa Yogananda.

“He would have been opposed to ideas of eugenics,” Smith said. “He wanted to look for the outlier, nurture it and create a good environment.”

Smith sees Burbank’s association with the eugenics movement as tied to Jordan’s attempt to build his own influence and reputation—and to tap into the grant pipeline that the famed horticulturalist had established. Burbank was a true celebrity in his time, with hundreds of people going to his gate to glimpse him and ask for photographs.

“The desire to have a little Luther Burbank rub off on your institution is very strong,” Smith said. “Which is why the eugenicists want to claim him.”

Even if Burbank’s connection to eugenics was tenuous, it speaks to a general thrust within the movement—the connection to nature. Some of the most prominent eugenicists envisioned a pure, glorious environment that was exemplified by California’s natural beauty.

“The redwood trees themselves were venerated by the eugenicists in the early 20th century, who thought the redwood trees were the pinnacle of natural beauty,” Stern said.

Current-day organizations ranging from the Commonwealth Club (opens in new tab) to Stanford University (opens in new tab) and Save the Redwoods League (opens in new tab) have had to reckon with this dark element of their pasts (opens in new tab).

“They thought they understood which species should be protected and which should be controlled and eradicated,” Stern said.

The eugenics movement was a part of mainstream California society. There was a eugenic section at the Commonwealth Club of California (opens in new tab), and a “human betterment” exhibit at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (opens in new tab) in 1915. Everyone from former President Theodore Roosevelt to Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger championed (opens in new tab) the benefits of eugenics.

“It’s the conservative in conservation,” Smith said.

Today’s Threat

The noble desire for self-improvement—so idealized in American society—has the potential to bleed into something much darker.

It’s not a threat that has gone away.

“Eugenics is very much with us today,” said Stern, who points to the public health discourse around Covid that she believes has demeaned people with autoimmune conditions or disabilities as expendable.

“The pandemic has exacerbated this question of whose life and health is valued and whose is not,” Stern said.

Stern also understands eugenics within the larger arc of California history, starting with the Spanish conquistadors who “had their own ideas of racial hierarchy,” followed by the Mexican period, Manifest Destiny and white settler colonialism.

“It all paved the way for what became this very extensive eugenics movement in California, which was really at the forefront of eugenics in the whole world,” Stern said.

Stern also sees a connection between eugenics history and the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision (opens in new tab) overturning Roe v. Wade. “It’s a long thread of reproductive oppression that goes back to Indigenous genocide as well as the full reproductive oppression associated with slavery.”

Dron, for her part, agreed. “How offensive it is to not allow people to exercise self-determination of reproductive desires?” she said.

“You devalue women, you devalue their children,” said Swarr, who has the personal experience of sterilization’s impact. “What’s going on today really bothers me because I see there’s a parallel, and I was hoping my grandchildren wouldn’t have to go through any of that.

“We’re so close to that again,” Swarr added. “The mood in the country is so right there.”