Tennessee effectively banned public performances of drag (opens in new tab), making it the latest state to get swept up in a moral panic over queer visibility in America. The backlash, which has singled out trans and gender-nonconforming people, appears to be a reaction against the gains LGBTQ+ people have made (opens in new tab) over the past few decades.

Restrictions on how people could present in public are nothing new, however. They date back well over a century and a half, to a moral panic after the Gold Rush. And progressive, free-spirited San Francisco was actually the first city in America to ban cross-dressing.

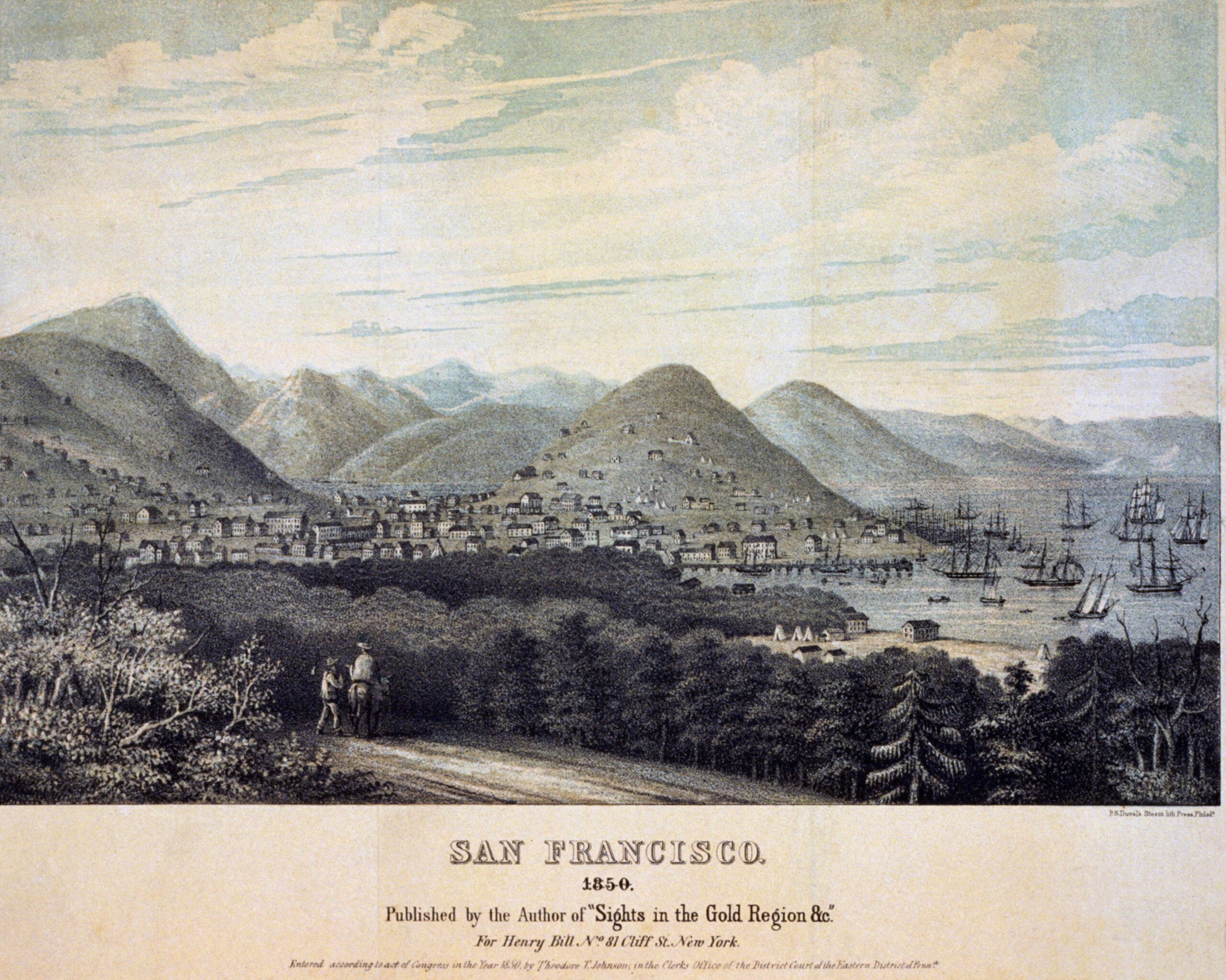

It’s partly because cross-dressing men were a part of the city’s culture from the very beginning. In the early 1850s, San Francisco was a boomtown filled with unmarried young men, almost all of them recent arrivals striving to make their fortune. Amid that gender imbalance, dances and balls where half the men dressed in drag—some for comic effect, others aiming for what RuPaul would call “realness”—were perfectly ordinary social events.

In their book Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco, Clare Sears writes that the figure of the cross-dressing miner (opens in new tab) was anything but taboo. Such men were celebrated for decades afterward as a symbol of California’s rugged early history. Unquestionably, some of them were what we would now call gay or trans—identities that didn’t exist then—but much of it was essentially frat boy-ish high spirits, or bros being bros.

The lawless Barbary Coast, with its violent bars, gambling houses and brothels, sprang up to serve these same men. Some female sex workers dressed in men’s clothing to move freely through male-dominated spaces. The Gold Rush ended yet San Francisco continued to grow, and its initial gender imbalance evened out.

Those young men started families, and cross-dressing became identified with licentiousness and the vices of the port. As San Francisco grew respectable, gender nonconformity in public became seen as a nuisance—another unpleasant element of city life, like the odor of slaughterhouses or sewage in the streets.

Sears writes that sensationalist journalism of the time made it appear that gamblers and sex workers ran the city, threatening San Francisco’s reputation as an economic hub where law and order prevailed. A backlash quickly developed, with crackdowns on public indecency and houses of ill repute—largely those run by Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. In 1863, the Board of Supervisors prohibited the act of wearing “dress not belonging to his or her sex.” By 1900, dozens of cities followed.

As with Tennessee today, San Francisco back then was concerned with gender expression in public, not in private—targeting people whose gender identity did not match with the sex they were assigned at birth, and leaving silly stag parties alone. Municipal arrest records from before 1906 were destroyed in the earthquake and fire, but newspaper accounts reveal that at least 100 people were arrested and fined for violating propriety.

Punishment didn’t just take place through the criminal justice system. Tabloids that ran stories detailing “problem bodies” seemed to denounce the scourge of cross-dressing. But they were simultaneously stoking the public’s voyeuristic and growing appetite for carnival freak shows. Meanwhile, “vice tours” of Chinatown’s dens of iniquity were meant to scare kids straight. It was all very Victorian: Images of untreated sexually transmitted infections were a form of moral education, but a woman in pants was an outrage.

It lasted this way, more or less, for about 100 years. In 1961, Jose Sarria, a female impersonator at the Black Cat (opens in new tab), became the first openly LGBTQ+ person to run for office. Sarria, who routinely wore a button that said “I Am a Boy” to evade arrest for dressing in drag with the “intent to deceive,” did not win a seat on the same Board of Supervisors that had banned cross-dressing a century before. But he staged a 1964 ball at which he crowned himself the Empress of San Francisco as a counterpart to the beloved 19th century eccentric Emperor Norton (opens in new tab), effectively connecting himself to the very period when the city was a pioneer in suppressing queerness.

The organization that Sarria founded, the Imperial Court, still produces drag balls today (opens in new tab). But it wasn’t until 1974 that San Francisco formally repealed its ban (opens in new tab) on non-normative gender expression. As with so much else about American life—from The Gap to bans on plastic bags—the backlash against queer people living their lives in public began right here.