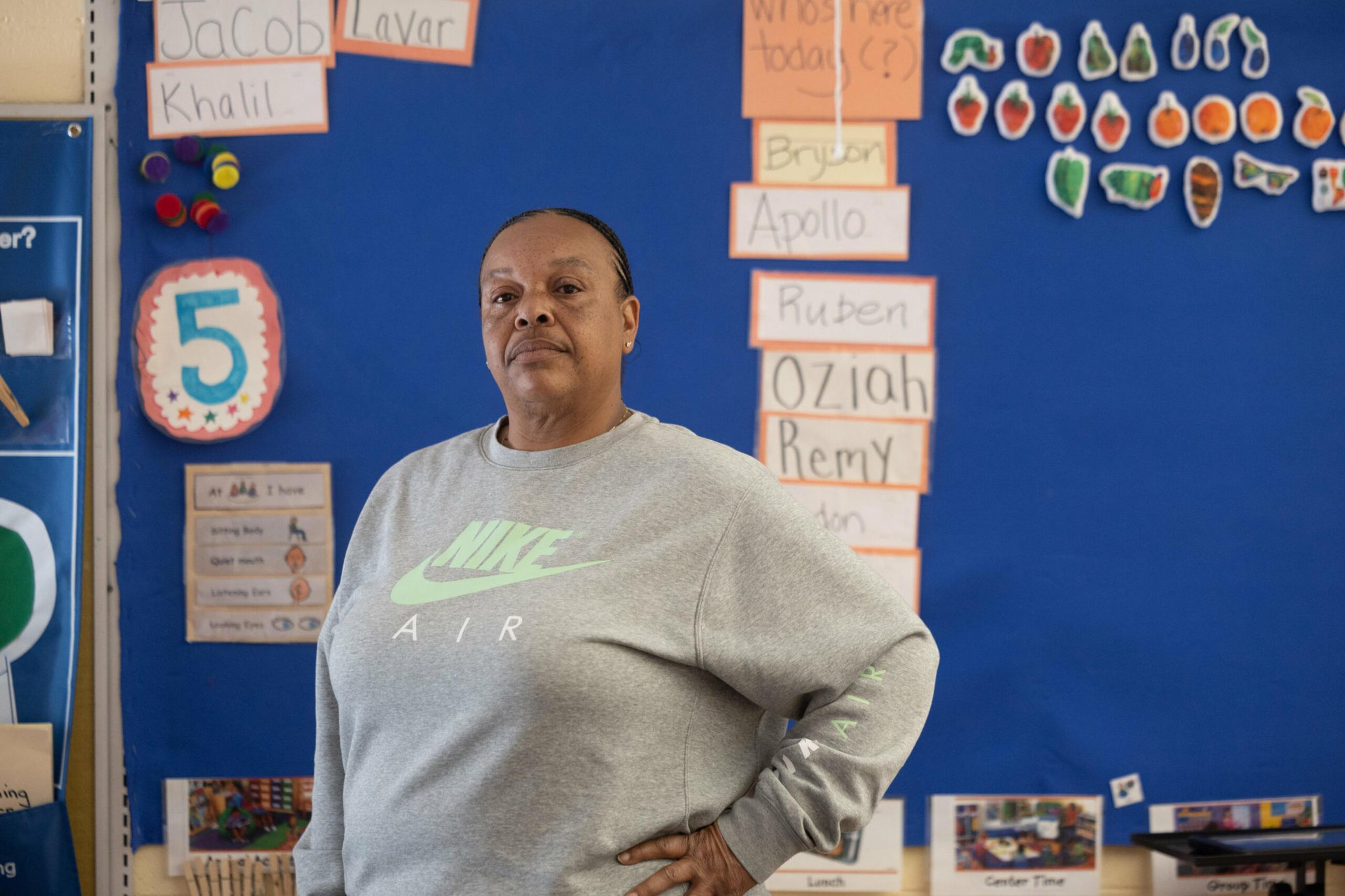

Roslyn Mardis has four jobs—or five, if you count the food truck she helps her son run.

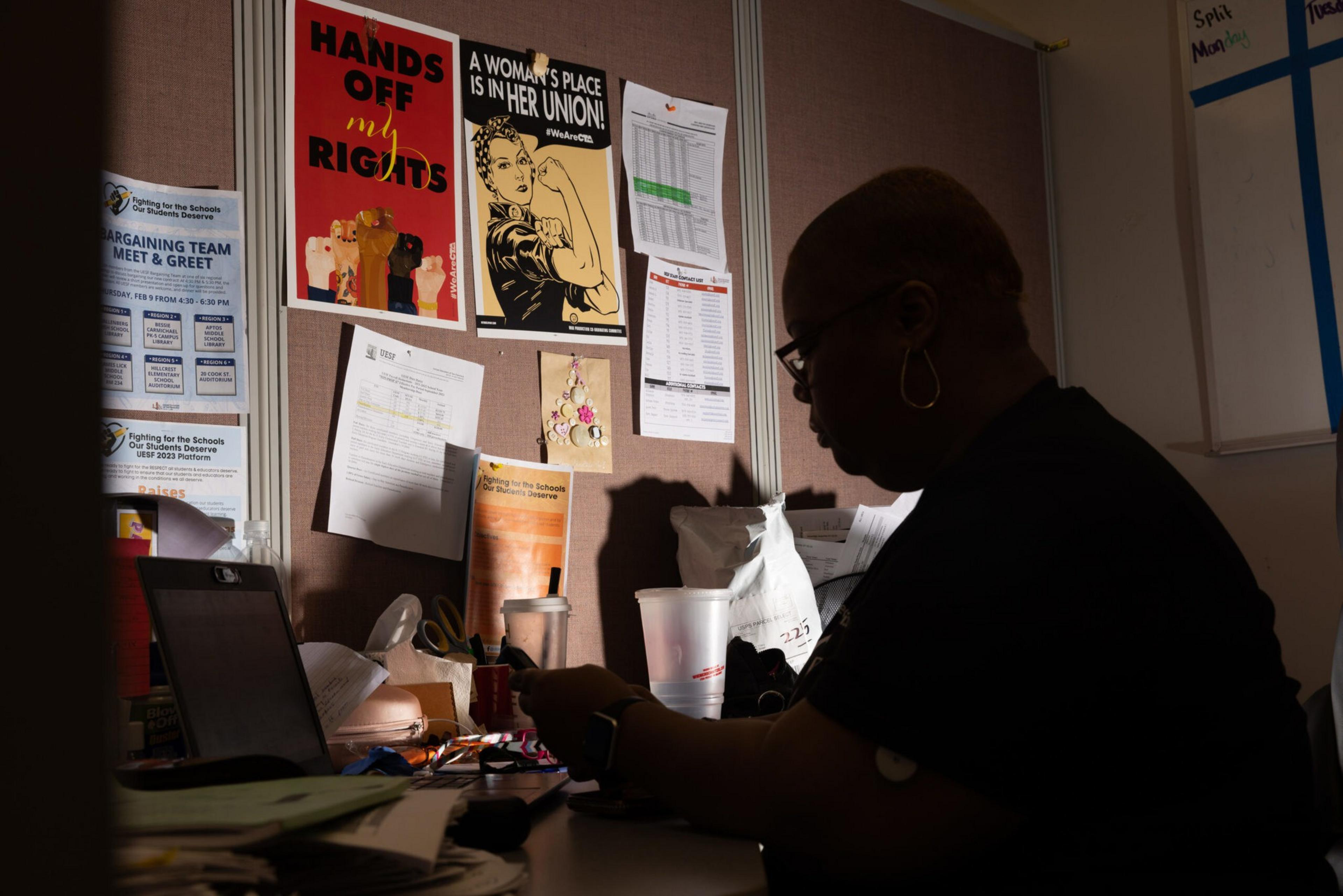

In addition to serving as a special education paraeducator in the morning and an afterschool paraeducator at a different school in the afternoon, Mardis works odd jobs on the side and occasionally plays the role of an accountant, due to the San Francisco Unified School District’s payroll saga.

The Bayview native has had to tack on additional gigs as the cost of living goes up and wages fail to keep pace. It’s hardly uncommon for paraeducators, who assist teachers, like Mardis to have second or third jobs.

And while Mardis loves being a paraeducator, it’s getting harder to get by with rampant inflation, rising energy prices and the cost of her son attending City College of San Francisco. Since she joined the school district in 2009, her hourly wage went from about $13 an hour to roughly $23 an hour.

“We are here for the kids. We love being able to shape their little lives,” Mardis told The Standard. “I can’t stay [in San Francisco] somehow off of love. I can’t pay PG&E with love. I can’t feed my son with love.”

As the school district prepares to negotiate its first full new labor agreement with the United Educators of San Francisco since 2017, the issue of paraeducator pay has emerged front-and-center. In September, the two agreed to an immediate 6% raise retroactive to the start of the year to address wage issues amid a record teacher shortage.

While paraeducators are not credentialed like their classroom teacher counterparts, they are trained to work as aides to provide individualized attention to children in a variety of settings. They are in special education classrooms, working to implement individualized learning plans, intervening in chronic absences, addressing behavioral issues, assisting English language learners, serving as liaisons to families and more.

“SFUSD values the fundamental role of paraeducators in supporting school communities,” district spokesperson Laura Dudnick said in a statement. “As a school district in one of the most expensive cities in the country, we are dedicated to doing everything we can to attract and retain qualified staff, including paraeducators.”

‘We’re the Invisible Workers’

There are about 200 paraeducator vacancies in the district, according to SF’s teachers union. Starting pay is currently $18.70 an hour, which will be mere cents above the city’s new minimum wage that starts in July—and paraeducators aren’t given full hours.

Without the ability to attract paraeducators and fully staff schools, the class environment can get dangerous. Alex Schmaus, a paraeducator who works with special education students, has had to receive medical care for a head wound caused by a student—and says they aren’t the only ones at their school to experience head traumas.

“You need to have adults to make sure the classroom is safe,” Schmaus said. “So that you’re able to give all the students the attention they need […] and get those needs met before behaviors escalate.”

Schmaus, whose mother and grandfather were teachers, estimates that their income would need to double to make a living wage. After rent and food, they essentially have no money left over.

Floating holidays are not enough to account for all of the school holidays, when paraeducators will often use PTO to keep the paycheck stable. Finding a summer job for 10 weeks can be tricky, as employers don’t want to lose a worker so quickly.

It’s not just about the wages, paraeducators like Schmaus say. It’s also about lack of respect, seen in the way they take on extra work outside their hours like getting students off the bus and investing in quality professional development time.

“When they give you marching orders, you have to march,” Mardis said. “As a para, what can you say? We’re there to make it happen.”

When asked why paraeducators may not be as valued, the teachers union’s Vice President for Paraeducators Teanna Tillery said background work is “easy to overlook.”

“We’re the invisible workers,” said Tillery, a paraeducator who works in attendance intervention and dropout prevention. “Sometimes, people don’t really pay attention to those who are quietly doing the work.”

Like a chunk of her fellow paraeducators, Tillery is also a San Francisco native who graduated from public schools. Many find their way to aiding classrooms accidentally, such as going from volunteering in their childrens’ schools to taking on paid positions.

Mardis worked in retail until it wasn’t feasible as a single mother and needed the same schedule as her son, then in kindergarten, to save on child care.

But to stay in the city, Tillery took on summer camps “until my body couldn’t take it anymore,” Instacart runs and other jobs that became available. Some fellow paraeducators work at grocery stores, while others have their own businesses like Mardis does.

After 14 years, Mardis is reconsidering whether to stay in the school district, depending on how the new agreement comes out.

“We’re all at school sites feeling the disasters of not having fully staffed schools,” said the union’s President Cassondra Curiel. “Bringing paraeducator pay all the way to what it should be has to go with respect.”

Without a significant pay raise, Curiel added, it will be harder to go into the next school year with new and existing teachers to properly staff schools.

“Then it sounds like a commitment to the deterioration and degrading scenario they have right now,” she said.