When Alfred Peet moved to San Francisco in 1955, two scents predominated the waterfront: fish and coffee. The fish might have been delicious, but the coffee was swill.

“I came to the richest country in the world, so why are they drinking the lousiest coffee?” Peet said (opens in new tab) of the ubiquitous Hills Brothers (opens in new tab) and Folgers coffee (opens in new tab) brands, then based in the city.

His discontent became our win, since the Dutch immigrant went on to create Peet’s Coffee.

Founded in Berkeley in 1966, the brand, which bills itself as “The Original Craft Coffee,” has been credited with revolutionizing the way Americans consume coffee, and for good reason—all three founders of Starbucks learned the trade from Peet.

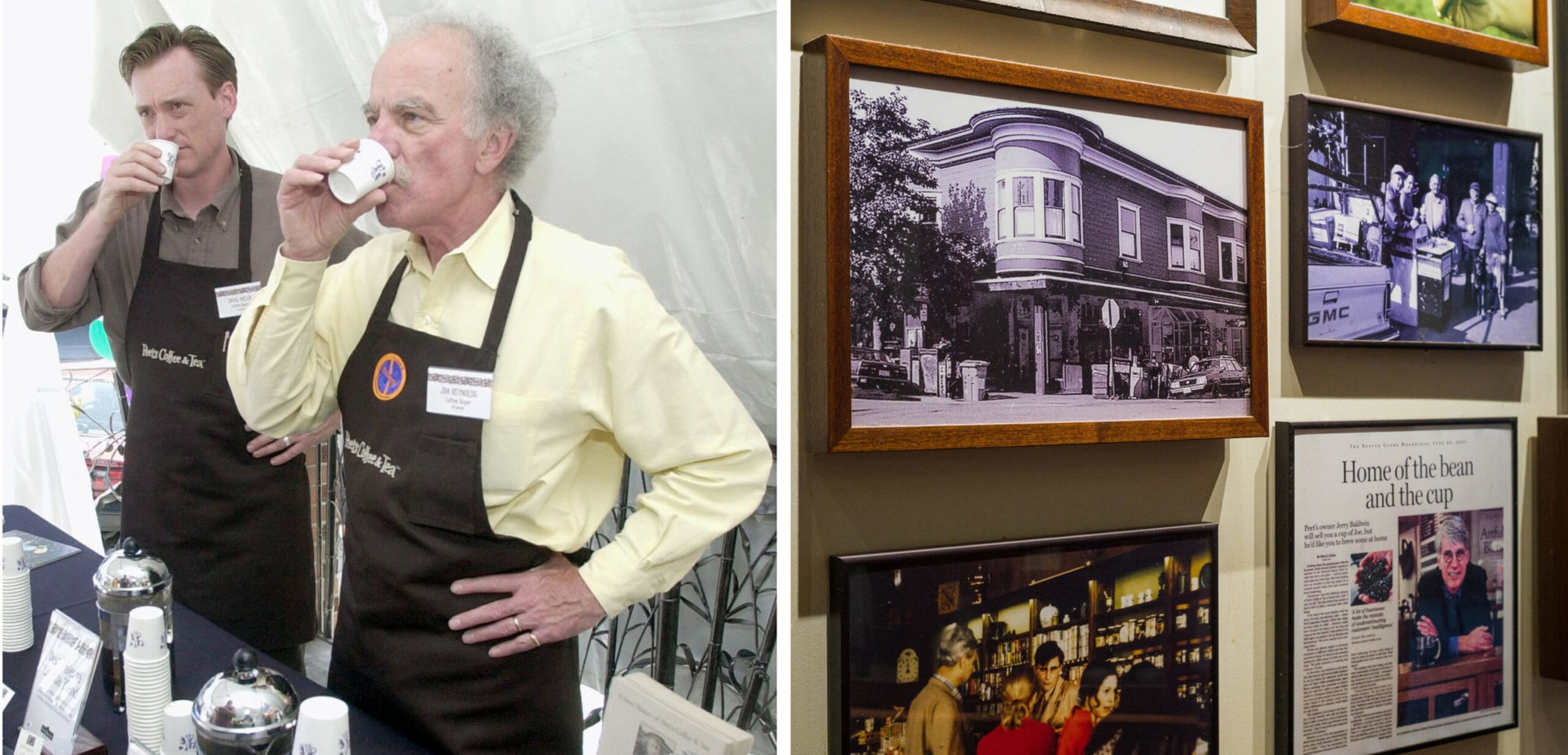

For the first year and a half of its existence, Starbucks bought beans directly from Peet’s to sell in its Seattle store, according to James Reynolds, former coffee roastmaster at Starbucks and coffee roastmaster emeritus of Peet’s.

“We had copied Peet’s. The whole place was modeled after what Alfred had done,” Starbucks founder Jerry Baldwin told Jasper Houtman, the author of The Coffee Visionary: The Life & Legacy of Alfred Peet.

Peet’s has since swelled to become part of the world’s largest publicly traded coffee company (opens in new tab), JDE Peet’s (opens in new tab), having acquired Mighty Leaf, Stumptown and Intelligentsia Coffee in the U.S. before being purchased by JDE.

It’s now launching its first ever to-go concept at the Peet’s location on Montgomery Street, where the store will be designed specifically around mobile orders—a far cry from the sip-and-linger vibe of a neighborhood cafe.

“It’s a result of consumer’s shifting habits, especially in San Francisco,” said Lorna Bush, a public relations representative for Peet’s, who noted the redesigned space would allow employees to focus exclusively on making drinks instead of tending to a cafe.

But would Alfred Peet, the venerated coffee guru who once had the uninitiated sitting at his feet (literally) for instruction and urged roasters to “listen to the beans,” approve of a sprawling brand with a to-go approach? The historical record suggests he might be just as disappointed by his namesake company’s expansive reach as he was with the watery coffee he first encountered upon moving to the Bay Area.

“The bigger a company grows and the more products it offers,” Peet told the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad, “the higher the chance that the quality of the product declines.”

The Singular Vision of Alfred Peet

Despite Peet’s global reach—with cafes from Shanghai to Dubai—for some, the brand holds on to its local vibe within the coffee conglomerate of which it is part.

“There’s a kind of a loyalty to Peet’s in the Bay Area that goes beyond its international reach,” said Kenneth Davids, editor-in-chief of Coffee Review, who noted that savvy young coffee connoisseurs still think of Peet’s as a cut above other craft java.

The company has also had an incredible consistency, with only three roastmasters in its entire 57-year history: Alfred Peet, James Reynolds and Doug Welsh, the last of whom started as a customer, then became a barista and worked his way up the corporate ladder to senior vice president and roastmaster (opens in new tab).

“One day, I found myself on the other side of the counter with an apron on,” Welsh said of his start at the company.

Despite the fact that Starbucks was initially modeled after Peet’s, the two companies have different company cultures, according to Reynolds. The Starbucks empire was built upon savvy marketing designed to make customers feel they are part of an elite club, while people fall in love with Peet’s because of its perceived authenticity.

You can see the distinction playing out by comparing the first Starbucks location in Seattle—which is constantly thronged with tourists taking selfies and buying commemorative mugs—to the original Peet’s, which is still in operation at the intersection of Vine and Walnut in Berkeley. It’s a regular café, where you can grab a cup, relax at an open table and check out the small museum in the back. Some of the location’s original customers still frequent the spot to this day.

Mark Pendergrast, author of Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World, reveres Alfred Peet’s contribution to roasted beans so much he dedicated his book to him, calling him a “coffee curmudgeon supreme.”

“Peet hated that,” Pendergrast said of the dedication. “But I meant it as a compliment.”

It was Peet’s exacting approach that allowed him to lay the foundation for what eventually would become a coffee empire, expanding from the Vine Street location in Berkeley to its more than 300 locations across the country today. The company opened its first international location (opens in new tab) in 2017 in Shanghai—10 years after Alfred Peet’s death—and now operates over 100 locations in China (opens in new tab) with products specific to that market, like “Coconut Snow Mocha” and “Wild Lemon.”

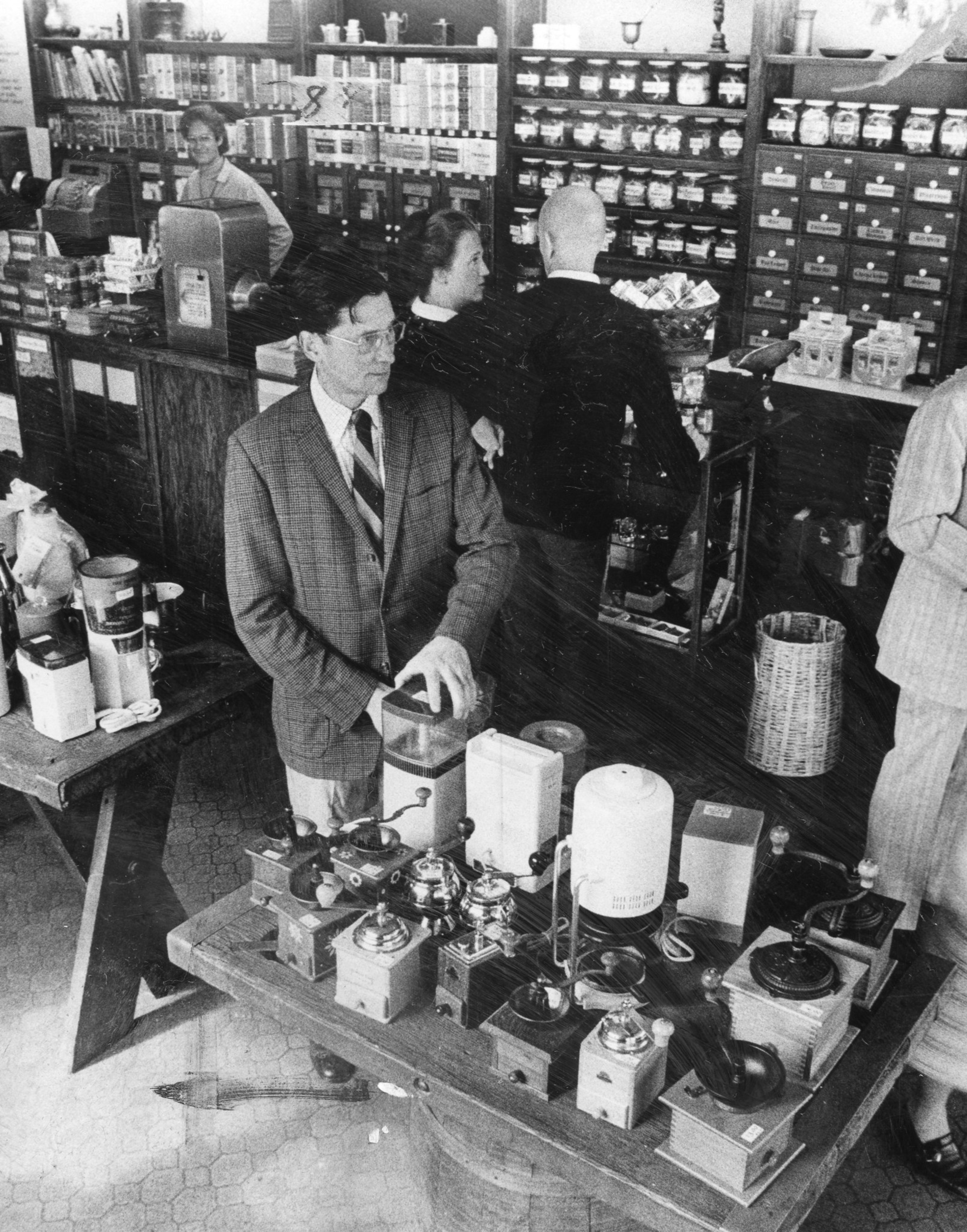

Dark roasted coffee was practically nonexistent in the Bay Area in the late 1960s. But Peet, who came from a coffee family in his native Alkmaar in the Netherlands and studied coffee roasting in Indonesia, created a mecca for home coffee consumption at his Vine Street location, with brass bins of fresh roasted beans in the front and a leather-aproned coffee roaster in the back.

A coffee perfectionist, Peet had little patience for those who did not take coffee as seriously as he did. “If he felt you weren’t genuinely interested in coffee, he would freeze you out,” said Davids, who knew Peet well.

When Peet’s opened in Berkeley, the store at first sold only whole beans for the consumer to brew at home. Pendergrast describes the scene of the cult-like roastery: “In the middle of a sentence, Peet would announce, ‘I have a roast!’ and rush over to let the rich brown beans tumble out. At this dramatic moment, all conversation stopped. For Peet and his customers, coffee was a religion.”

Even though Peet’s is far from the first craft roastery in the Bay Area—that designation would go to the 1935 Graffeo Coffee in North Beach (opens in new tab) (still roasting today) or the 1899 Freed, Teller & Freed (opens in new tab)—it was the one that hooked people on dark roasted coffee. The store also benefited from its location. Within a year, the famed Cheese Board cheese shop opened nearby and other foodie businesses soon followed: the Produce Center, Pig-by-the-Tail charcuterie and Cocolat chocolate shop.

“We sold a tremendous amount of coffee beans, and the lines were unbelievable, especially during the holidays,” Reynolds said. “Even on a daily basis, there were usually about a dozen people waiting in line to buy coffee beans.”

The café exuded an aura of cool and, much to Peet’s dismay, was frequented by Berkeley hippies and beatniks. Dedicated Peet’s customers were called “Peetniks,” a name still used today for the company’s reward program (as well as newly hired employees).

“Peet thought the hippies were gross-looking and needed to shower,” Pendergrast said.

The Dutch coffee roaster’s spirit lives on—or you could even say haunts—the business today.

“Everything reminds me of him,” Welsh said, and proceeded to tell a story in which Peet admonished him for not smelling the beans directly after grinding. “He was giving me the Mr. Peet glare, which was not an easy thing to endure.”

It follows a pattern of Peet’s often perfectionist demands, which gave him the reputation as challenging—even scary.

One self-described Peetnik, Peter K., has been frequenting the Vine Street location several times a week since 1969, when he was in his mid-30s. He remembers paying only 40 cents for a cup of coffee and also when there used to be seating outside the café. He also remembers the discerning nature of Alfred Peet himself.

“Peet was working behind the counter, and this veteran woman barista did something to displease him, and he scolded her in front of everyone, all the customers,” he said. “I just thought how terrible it was. And that’s been my lasting memory of him.”

Craft Gone Corporate

According to Pendergrast, Peet’s is well positioned within the coffee industry. He views its merger with the Dutch coffee brand Douwe Egberts and its expansion into China as promising signs for the Peet’s brand. Coffee consumption itself continues to climb—2% per year, according to Welsh—which gives Peet’s a baked-in advantage to source new customers.

Yet the coffee industry itself faces numerous stressors, from which Peet’s is not immune. Coffee rust disease (opens in new tab), coffee (opens in new tab) berry borer beetles (opens in new tab) and climate change have presented big challenges in recent years—to say nothing of the pandemic.

JDE Peet’s stock is down 33% in the past five years (opens in new tab) and Peet’s has shut at least one SF location recently. Is it a sign that the coffee behemoth has grown too big for its to-go tumbler, or are these just normal fluctuations one would expect to see during turbulent economic times?

“Trying to get the mix right in Downtown San Francisco is complicated,” Mary O’Connell, communications director of Peet’s, said of outlets closing. She noted that customers’ habits are changing, and more people are buying coffee to brew at home. According to O’Connell, store closures have not resulted in the termination of their employees, who have been shifted to other locations.

The drop in stock could also be prompting what feels like a furious scramble to keep up with trends and consumer demands, whether it’s the to-go location on Montgomery Street or the addition of boba-inspired “jelly drinks” to the menu.

The company has also had worker complaints, first with a group of baristas protesting the reopening (opens in new tab) of locations during the pandemic and a (successful) push for unionization at the North Davis location (opens in new tab).

Alyx Land, shift lead at a Peet’s location in Davis, has seen some troubling patterns as Peet’s becomes more corporate, such as increased work expectations for less pay.

“We’ve tried everything, but it was only getting worse,” said Land, who has worked at the Peet’s location for five years. “We realized the only possible way to get change was to unionize.”

Land spearheaded a unionization movement, and workers at the store voted 14-1 in favor of joining the Service Employees International Union in January. They described an environment with a high turnover rate, frequent manager changes and reduced training—all to maximize profit at every possible turn.

It has led some to draw comparisons (opens in new tab) between Peet’s and its younger sibling, Starbucks. Critics have said that an emphasis on speed, productivity and profit margins has tempered the personal feel with corporatization.

“I really love what I do,” Land said, citing the active nature of their job and the craft of latte art. “That’s why I want to stay and fight for change.”

Yet not everyone feels the way Land does. At a San Francisco branch of Peet’s at Brannan and Eighth streets, a barista pointed out the excellent benefits of the company.

“At 21 hours a week, we get full medical, dental, vision benefits,” an employee at the store recently said. “I don’t know of any other coffee company that does that.” The barista said she has worked at the cafe for two years—what she says is the average for employees at that store.

Despite Peet’s morphing into a sprawling corporate entity, one feature synonymous with the brand has held true, even for Land: quality.

“It’s genuinely good coffee,” Land said. “And that keeps me loyal.”

Reynolds’s favorite blend remains the Guatemala Antigua blend, which is still available today. “Peet’s has been buying that coffee for 40 years from the same farm, and it’s the best quality coffee from Guatemala.”

If Peet’s (with its dark roasting) begat Starbucks and Starbucks (with its milky espresso drinks) begat a type of coffee retailing that’s imitated throughout the world, the “third wave” of specialty coffee emphasizes light roasts with less milk and more emphasis on the source, according to Davids.

But even when you’re trying out new things—like the boba-inspired drinks Peet’s recently added to its menu in an attempt to lure the Gen Z crowd—you still have to keep the regulars happy.

“It’s kind of a delicate balancing act that both Peet’s and Starbucks have to do,” Davids said. “But Peet’s approached it in a much more sensitive and thoughtful way.”

Nevertheless, the company’s attempts to woo younger customers can at times seem to stray too far off course.

“The jelly drinks don’t make sense,” Land said of the recent additions to the menu (opens in new tab), noting that Peet’s is not a boba shop. “Plus, they’re a pain in the ass to make.”

The attempt to meet customers where they are—whether it’s with boba or a to-go shop—may meet market demands, but is it consistent with the vision of the founding roastmaster, whose spirit lingers everywhere?

“I believe in Peet’s values,” Land said. “I just don’t believe they follow their own values, and it’s gotten more and more complicated as time has gone on.”

Yet many craft practices are still in play at Peet’s, even with the company’s growth. Every coffee the business sells—from China to the United Arab Emirates—is selected and tasted in the cupping room in Emeryville, which is named in honor of roastmaster emeritus James Reynolds.

Watching Welsh “break the cup” by dipping a tasting spoon into a slurry of coffee grinds and proceed to inhale and slurp demonstrates his commitment to quality, one that calls to mind Alfred Peet’s spirit.

“Coffee is alive and has a personality,” Welsh said.

Correction: Doug Welsh is senior vice president and roastmaster at Peet’s.