“Abandon All Hope Ye Who Enter Here” reads a neon sign in an eerily inviting cursive at the Misalignment Museum (opens in new tab) in San Francisco’s Mission District.

Descending the staircase below where the glowing script hovers against a lush backdrop of plastic fauna, a visitor can’t help but wonder if the message is an ironic invitation to explore or a warning on the future of artificial intelligence—the subject and star of this art pop-up on Guerrero Street.

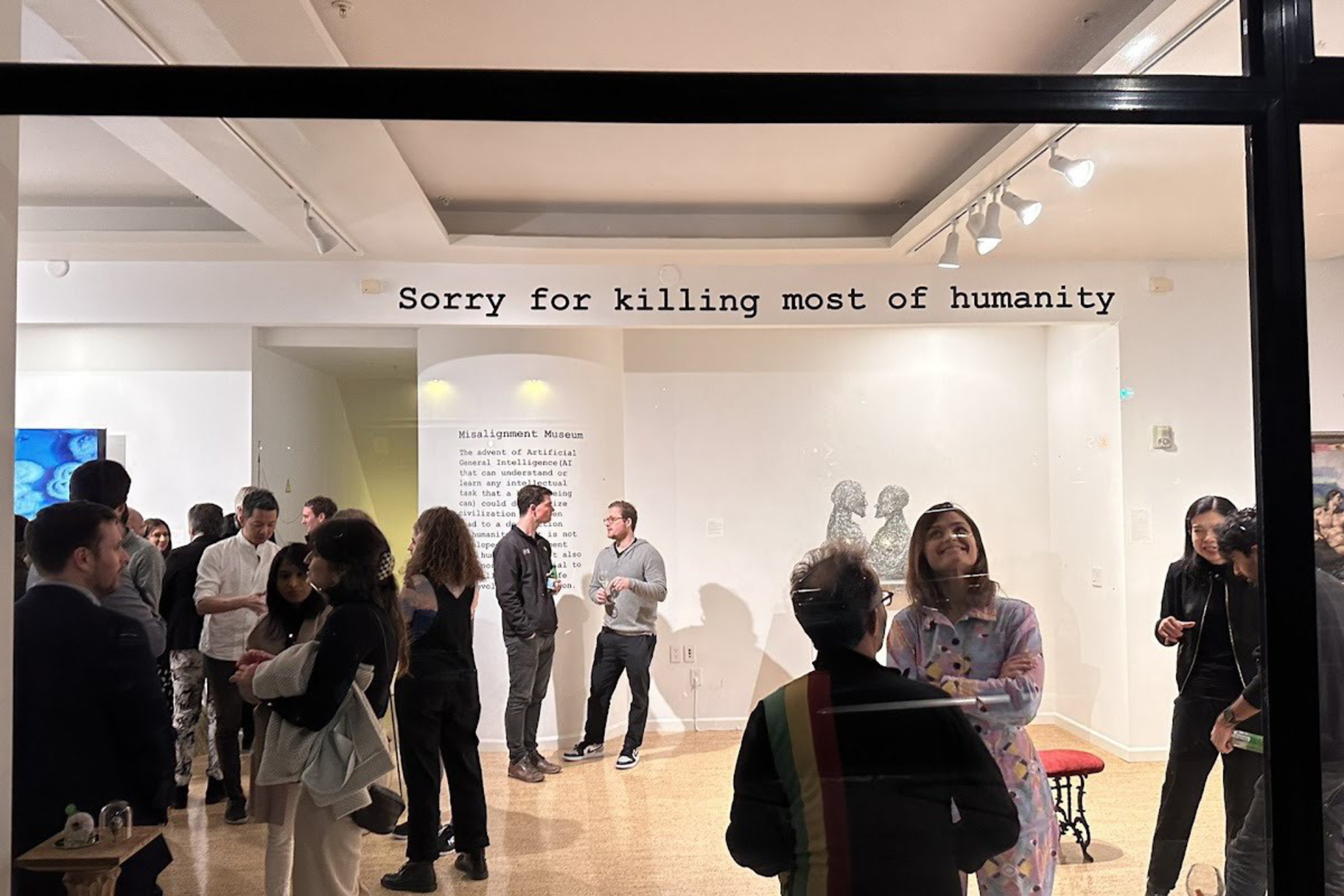

The temporary museum made a media splash this spring with its apocalyptic premise (opens in new tab) and imagines a world in which AI has practically exterminated the human race. The fantastical art pieces and fictive artifacts within it are a kind of apologia, a way of saying sorry to the humans that technology’s ruthless takeover hasn’t yet left for dead. There’s even a wall that reads, “Sorry for killing most of humanity.”

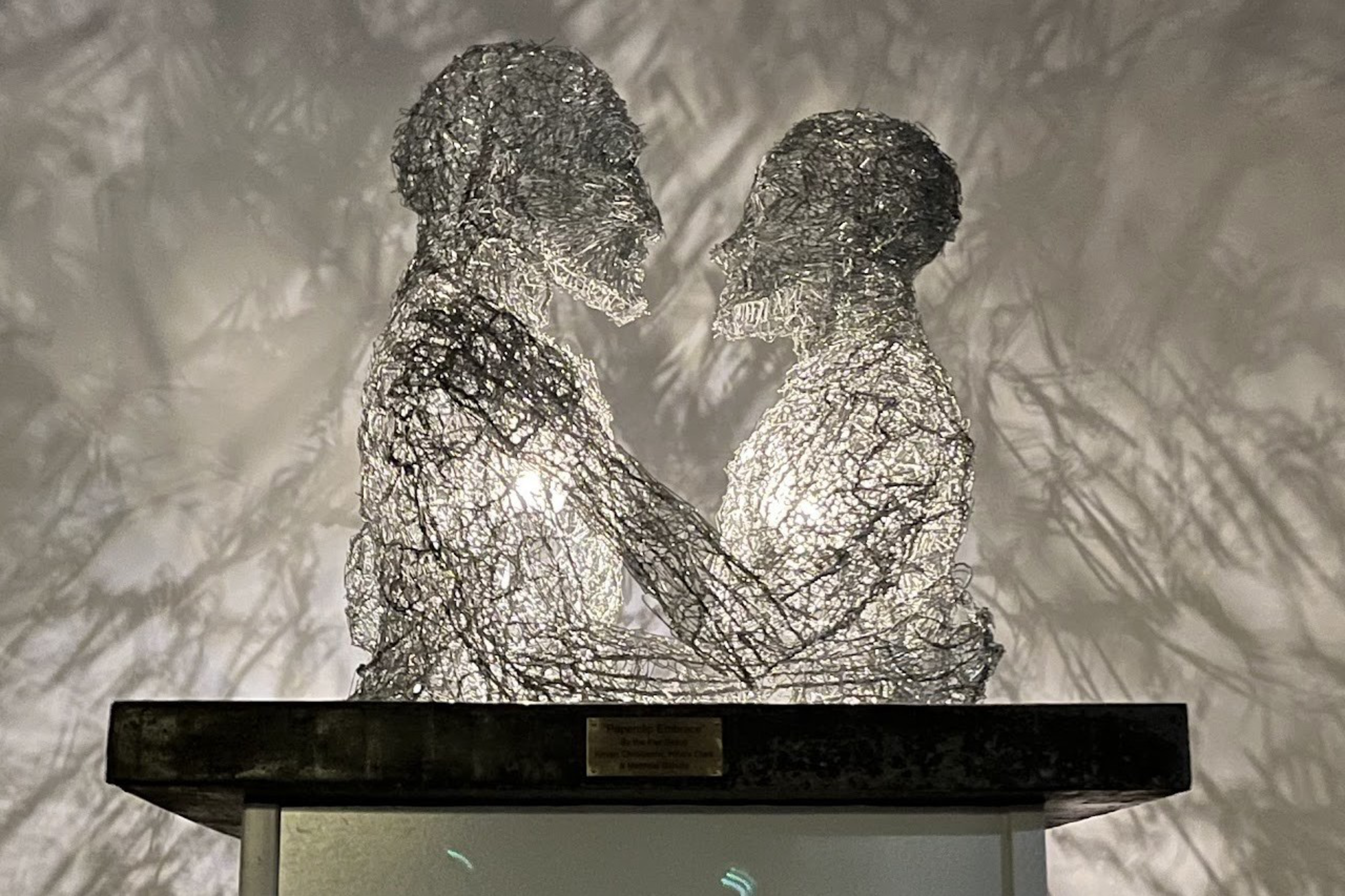

Yet even amid these signs of death and destruction, there’s beauty and whimsy. A glow, like a heart lit on fire, emerges from the chests of a paper-clip sculpture of two human figures embracing, and a player piano makes music to the growth of luminescent microorganisms projected on a television screen—leaving one to wonder if maybe AI is not a nail in the coffin of mankind after all.

The potential promise and perils of AI are among the weighty matters museums across the country are wrestling with as ChatGPT charges forward (opens in new tab), text-to-image generators raise legal and ethical questions on artistic authorship and ownership, and record labels scramble to get AI-powered deep fake songs pulled from streaming music services.

Some U.S. cultural institutions have tackled the technology head-on. They use whimsical art to prod patrons into a state of contemplation or engage visitors with immersive performances and interactive installations. Although the medium and messaging may vary, contextualizing the rise of AI is key.

Good or Evil? You Decide

While the jumping-off point for the Misalignment Museum is dark and dystopian, founder and curator Audrey Kim says the space isn’t simply playing out an AI doom loop. Rather, Kim hopes to educate visitors about the positive and negative powers of AI, so that visitors can consider the technology on their own terms—without having to sort through complicated and endless tweet threads.

“Our goal is to mostly create a space for people to really be able to reflect on the tech itself,” said Kim, an ex-Googler and former Cruise employee. “I also want to create a space where we’re not saying everything is ‘doomsy,’ because I think there’s a lot of really potential good for AI.”

Case in point, a dashboard that displays the number of humans who have died of cancer since AI cured the disease in the museum’s imagined future: The number is zero.

A pack of autonomous Roomba vacuums capped by broomsticks, or “broombas,” roving about the basement illustrate AI’s foibles. On the one hand, they recall the enchanted brooms that Mickey Mouse loses control (opens in new tab) of in Fantasia. On the other, their madcap dances across the room border on absurdist theater—their innocent bumps into human visitors are more funny than sinister.

“I think that humor creates more of a palatability to talk about this topic,” Kim said. “I think it’s easier to inspire and motivate people with joyful, fun things, [rather] than ‘You’re gonna die.’”

The Museum of AI (opens in new tab), a bootstrapped series of pop-up performances and AI salons that plans to come to the Bay Area this year, also uses humor to demystify the technology.

In one immersive experience, participants enter a traditional museum-i-fied lobby where they can look at tongue-in-cheek objects such as “ANNA,” a “retired” early AI chip that never reached the mass market and now “lives quietly in comfort and style” perched on a miniature white couch. Another fantastical flight of AI fancy is a “bloodshot-eyed moth” encased in glass that nods to the first insect that pioneering computer scientists like Grace Hopper uncovered in their machines (opens in new tab) and refers to so-called computer bugs “vexing humans ever since.”

“Everything we do is either a little unconventional or pretty weird,” explained Tracy Allison Altman, the founder and executive director of the Museum of AI. “We always try for funny whenever we can. It’s supposed to be a way of introducing AI to people without scaring them, so we don’t do killer robots.”

Altman hopes to show that AI is neither good nor bad, nor sentient, but simply a string of man-made code riddled with human flaws.

“I like to say it’s not a bad robot or a good robot,” Altman said. “It’s just a robot.”

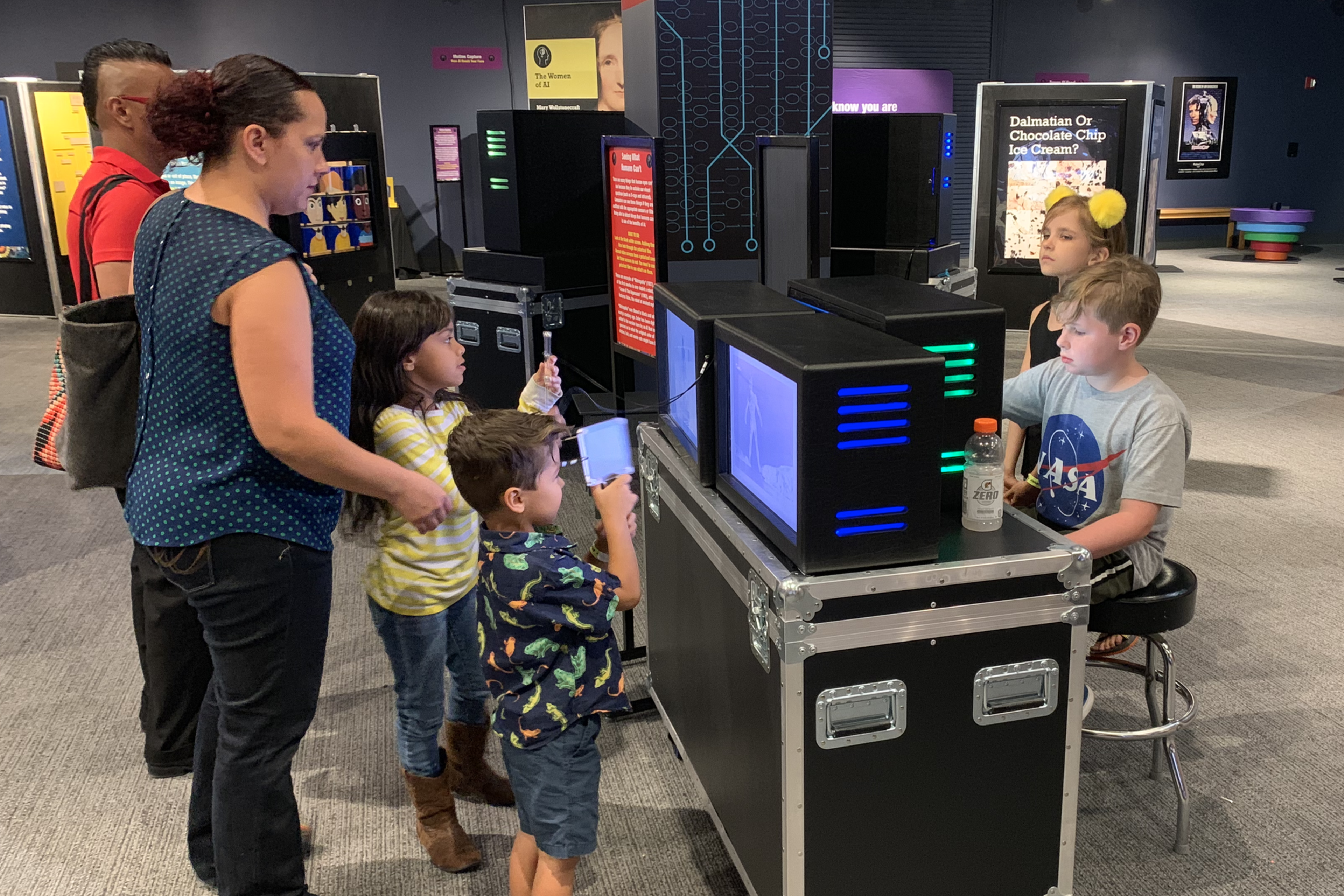

Other exhibitions, like the traveling exhibition Artificial Intelligence: Your Mind & The Machine (opens in new tab), which comes to Redding, California, in September, cast a more realistic and less fanciful eye on the technology. Conceived by author and technologist HP Newquist, the exhibition covers the history of machine learning while comparing how humans and machines process information through illusions, videos, puzzles, board games and interactive stations.

While Your Mind & The Machine also covers how AI pops up in everything from classic sci-fi books to popular movies, Newquist says that the intention of the exhibition is to show the present capabilities of AI and how it already appears in our everyday lives—in commonplace applications such as Netflix or Google Maps.

“To a lot of people, [AI] means everything from the Terminator to RoboCop to R2-D2,” Newquist said. “What we’re trying to do for the general public is make it both real and relevant. We want people to understand generally what AI can and cannot do.”

But the exhibition also goes into the potential dangers of widespread surveillance and misinformation on society and asks visitors to contemplate a number of potential outcomes for AI in the future.

“Is AI used for good? Is AI used for bad? Is AI something that we completely ignore […] or is it something that becomes so powerful that we become subservient to it?” Newquist asked, summarizing the exhibition’s parting panels.

Ultimately, he hopes that the exhibition helps visitors think critically about AI and confront it face-to-face because he believes time to evaluate the technology is rapidly escaping us.

“The train has left the station,” Newquist said of AI. “It doesn’t mean it’s reached full speed and that we can’t jump on the caboose and get back on to it. But it has started moving. And we can’t sit around thinking, ‘Well, we’ve got time.’”

The Future of AI in Art Museums

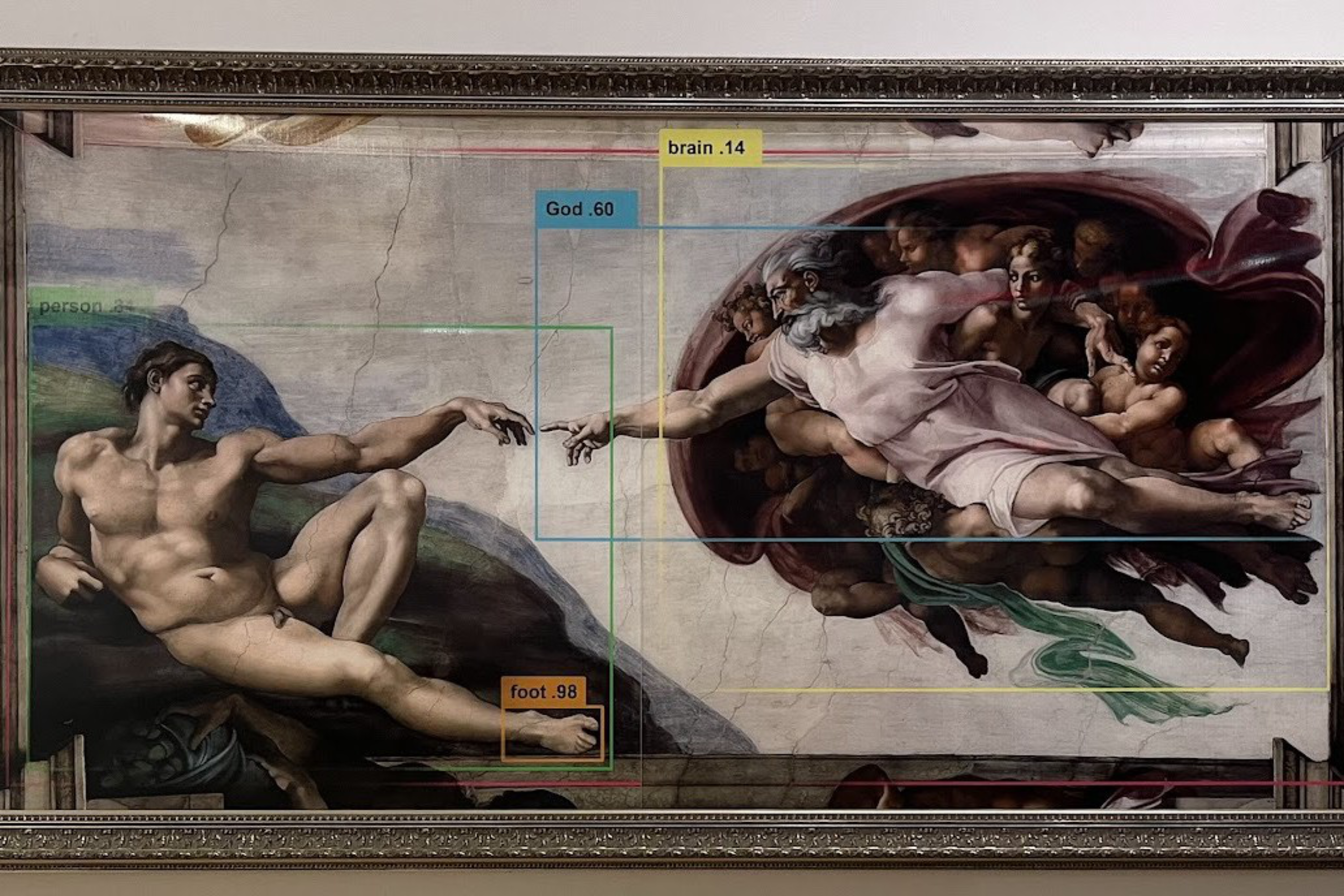

For technologists at the intersection of art and the digital worlds, artificial intelligence offers exciting creative possibilities but also challenging legal, ethical and curatorial questions about authorship, acquisition, ownership, provenance and authenticity. These and more were the focal point of a recent panel discussion at Art Market San Francisco on the impact of AI on creators (opens in new tab).

Moderator Niki Selken is a former creative director of Gray Area (opens in new tab), a cultural incubator in the Mission that integrates art and technology. She observed that image copyright questions (opens in new tab) and uncertainties over the ownership of large language models are currently confounding curators and museums alike.

“If you’re a curator selling to people or if you’re a museum curator, there’s a lot of unknowns in terms of the legal ramifications of model usage that are still being ironed out,” Selken told The Standard. “Until the laws are proven one way or the other, I think it is literally a gray area about who owns these works.”

Gray Area artistic and executive director Barry Threw echoes Selken’s concerns.

“Some of the old legal tools we used to think about authorship are being stretched by this technology,” Threw said.

Aside from tackling legal issues and reevaluating their curatorial practices, he believes that cultural institutions will have to step up their educational game and support of artists creatively and economically.

“It’s up to us to really make sure that we’ve thought through how creators can make a living in our society and how we value them,” Threw said. “How do we ensure a future that’s regenerative and livable for everyone?”

‘The Early Stages of a Quantum Shift’

The role of cultural institutions in a world where AI now roams relatively free was one of many questions at Museums of Tomorrow (opens in new tab), a recent symposium on museums and digital technologies at Stanford University. Hosted by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and Cantor Arts Center, the program brought together museum leaders, artists and academics from around the world to discuss how tech, such as AI, could shape cultural institutions in the very near future.

Everything from an analog catalog of swatches transformed into an online library to interactive screens where visitors can download metadata from collections were presented as examples of how museums could employ cutting-edge technology. At the same time, legal questions of licensing and image copyrights bubbled up from the audience. The conclusion was that museums—traditionally centers of cultural authority—are at an inflection point for contending with digital technologies.

“How do the public, creators, cultural workers like us, distinguish modern technologies from magic?” asked Seb Chan, the CEO and director of Melbourne’s Australian Centre for the Moving Image. “Whilst we may be in the early stages of a quantum shift, there are multiple presents. There are also multiple futures. We have a choice in this.”

While AI’s gray areas may raise legal, ethical and economic concerns, Tom Campbell, director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, does not think museums will go the way of the dodo but remain a forum for critical engagement with art—whether made by a computer or not.

While Campbell said that his organization, which oversees the city’s two fine art museums—the de Young and Legion of Honor—does not currently have a formalized policy for acquiring AI-generated artwork, he noted that NFTs and AI artwork are eligible for the de Young Open this year. Further, he anticipates that current acquisition and citation processes for the museums won’t change radically with the proliferation of AI.

“I think we will be especially alive to these issues of ethics and copyright,” Campbell said. “But I imagine they would be not dissimilar to the protocols we follow now.”

While he thinks that AI could be a powerful tool for how museums search databases and conduct research, he believes that AI will have the most impact on visitor behavior—with AI unlocking more access points and sources of information for patrons to pull up on their digital devices.

“Now, I think more and more we have a blended world where museums continue to do their best to provide thoughtful commentary. But at the same time, visitors can access alternate points of view through handheld devices,” Campbell observed. “I imagine that is a process that will only expand.”

While economists worry that AI could eliminate millions of jobs (opens in new tab), Campbell is not worried about the staying power of the museum.

“For the vast majority of museums, the role is to physically bring people face-to-face with physical objects,” Campbell said. “We are humans. We are not chatbots. And while chatbots may enhance our experience, they will never replace that primary experience of being a human in a space with objects that may be beautiful or challenging or upsetting, but that are fundamentally addressing us as humans.”