The most important phone call of London Breed’s career went to voicemail. So did the next call. And the next.

San Francisco police had already been dispatched to Breed’s apartment in the middle of the night when she finally picked up the phone and got an inkling of just how drastically her life was about to change. Earlier in the evening of Dec. 11, 2017, Mayor Ed Lee had suffered a heart attack while grocery shopping. As president of the Board of Supervisors, Breed was first in line to the throne.

She arrived at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital in an ashen state, according to one of the many city officials who stood vigil that night. Doctors were struggling to keep Lee alive, but word was spreading that he would be severely incapacitated even if he survived. Breed joined the mayor’s chief of staff, Jason Elliott, and another advisor in a conference room as they waited for news. At 1:11 a.m, Lee’s heart took its last beat.

“I told her: ‘You’re the mayor now,’” Elliott recalled. “And that was the beginning.”

Breed showed grace under pressure in the role of acting mayor and rallied the city in the days to come. But in short order, Breed’s colleagues would turn against her, forcing her to mount a historic campaign to become San Francisco’s first elected Black woman mayor. She was propelled into office by a diverse but moderate-leaning coalition of voters, garnering strong support from women and people of color as well as real estate and business interests. But the honeymoon would be brief.

Breed’s handling of Covid was widely praised, but the vulnerabilities of a local economy disproportionately dependent on tech would soon be exposed. For years, San Francisco’s tax coffers had been bursting at the seams, but a debt was coming due amid a new era of remote work. All the while, the widening gulf between haves and have-nots coupled with hopeless bureaucratic stonewalling had exacerbated issues around housing, homelessness, drug addiction and property crime.

Five and a half years after Lee’s death, Breed now stands at the helm of a city in turmoil.

San Francisco’s reputation as a bastion of innovation and liberalism has given way to narratives about wasted potential and American rot. The city is on pace for a record-setting 800 drug overdose deaths this year; tents, discarded needles, artless graffiti, psychotic breakdowns and sidewalk scat are common even in some affluent neighborhoods. Property crime is rampant, and—despite a dip in the market—the idea of owning a home in the city remains a pipe dream for most as median home prices hover at around $1.3 million.

Major retailers such as Whole Foods, Nordstrom and Old Navy have decided to shutter their flagship stores. Remote work has emptied out almost a third of San Francisco’s office space, contributing to a $780 million budget deficit and leaving Downtown skyscrapers to sit like ghost towns with panoramic views of the bay.

More than three-quarters of San Franciscans believe the city is on the wrong track, a recent poll showed, and Breed’s approval numbers are plunging.

Breed’s tough talk on crime and blame game with “lefty” political opponents is wearing thin. Frustrated residents are questioning her vision for the city and turning a critical eye to her performance. Meanwhile, potential challengers are kicking the tires on campaigns to defeat her in 2024.

Over six months, The Standard interviewed more than 50 people close to Breed, from friends and neighbors in the Western Addition housing project where she grew up to associates and colleagues in City Hall. The portrait that emerged from these conversations is that of a sharp-tongued but sincere leader. Breed is charming, intuitive, community-driven and wickedly funny, a people person just as capable of connecting with minimum-wage street ambassadors as high-society power brokers.

However, behind closed doors, some of Breed’s strongest traits cut both ways. The 48-year-old mayor’s bluntness can complicate collaboration. Breed doesn’t micromanage, but some say she over-delegates leadership to overwhelmed department heads and staff who are running on fumes. Supporters praise her willingness to try new strategies to confront the generational crises plaguing San Francisco, though they admit the implementation can be scattershot.

The mission of being mayor is deeply personal for Breed. Unlike most of the city’s politicians, her life was profoundly shaped by many of the same ills now roiling San Francisco: poverty, addiction, crime, mental illness and housing and economic instability.

“You grow up a certain way, and you remember it like it was yesterday,” Breed said in an early June interview with The Standard. “The fact that I even graduated from high school and ended up in college and graduated from college—for me, it’s a big deal. And it also makes me live like I have nothing to lose.”

A ballot measure passed last year pushed the mayor’s race to 2024, extending the tightrope Breed must traverse to reelection. To secure a second term and become the longest-serving San Francisco mayor in almost a century, Breed will need to solve—or at least alleviate—the problems of a broken city that have been decades in the making.

This is far from the only time Breed has faced extreme pressure. But even some of her most ardent supporters are uncertain if she’s capable of answering the call.

“Is there a feeling of vulnerability?” asked one of the mayor’s closest allies, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “One hundred percent, yes.”

Chapter I: ‘You Can’t Mess With Her’

“The reason she doesn’t go into that is because it’s not just her story. It’s her mother’s story. It’s her family’s story.”

— Sheryl Davis, executive director of the San Francisco Human Rights Commission

The mayor is fiercely protective about telling her family’s story—in part due to the tragedies she endured, but also because she herself doesn’t have all the answers.

Breed’s mother was absent much of her childhood and their relationship is complicated. The mayor does not know the identity of her father. She recently took a DNA test and learned she is half Jewish, a discovery she revealed privately to a group traveling with her on a Sister City trip to Haifa, Israel (opens in new tab), in May.

“I don’t want to talk about my family in a way that throws them under the bus,” Breed told The Standard in the second of two sit-down interviews for this story. “The fact is, I don’t know my biological father, and I’ve recently made a discovery that I have not made public in any way.”

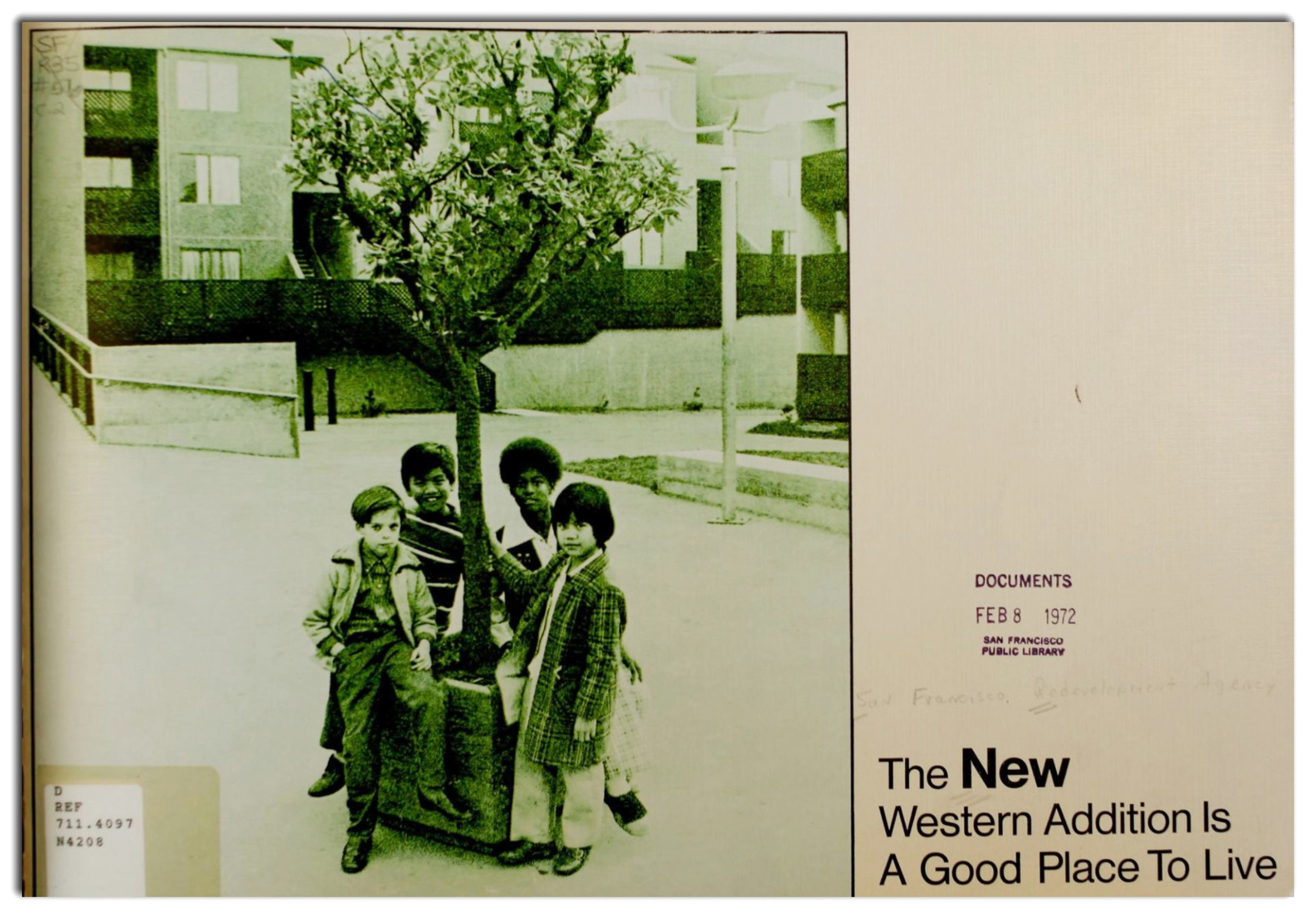

Breed was born at Kaiser Hospital in San Francisco on Aug. 11, 1974, and spent her earliest years living with her grandmother, siblings and two aunts in a cramped apartment in Plaza East, one of the city’s toughest public housing projects and the epicenter of a murderous turf war between rival gangs.

“If you were not Black or didn’t live there, you could not come to these projects,” Breed said. “You had to say a name. There was a name that had to be used—otherwise, you couldn’t walk through there at all. You would get robbed. You would get beat up, everything.”

At 12 years old, Breed saw the corpse of a person who had been shot in the head. In her 20s, one of her brothers took part in a deadly robbery and was sentenced to prison. In 2006, Breed lost a younger sister to a drug overdose, and one of her cousins was killed by police. Over the years, officers were routinely called to help with one of Breed’s aunts, who suffered from mental illness and explosive fits of rage.

The kindness shown by these officers, including a cop whom Breed’s aunt lovingly nicknamed “Beefcakes,” shaped the mayor’s nuanced views on policing. As a supervisor, Breed called for a federal investigation into the police killing of Mario Woods (opens in new tab); as mayor, she has advocated for a crackdown on people using drugs on the streets, expanding police surveillance tools and hiring more officers.

“Folks don’t realize that, by and large, Black people are pretty conservative when it comes to what public safety looks like,” said Sheryl Davis, the head of the city’s Human Rights Commission. “They’re not always against the police. They just don’t want the police to be brutalizing them.”

Breed’s grandmother, Comelia Brown, was a Baptist faithful to the good book. Miss Brown—as she was known throughout the neighborhood—served as the family rock, the guiding light and the hammer that forged Breed into the person she is today.

“She was a church lady,” said Rev. Arnold Townsend, who was present at Breed’s baptism and helped officiate the funerals of the mayor’s grandmother and sister. “And in the Black community, that means a certain thing—very, very stern and can be quite severe when necessary.”

Under her grandmother’s watch, Breed and her siblings were required to cook and clean, make their beds and go to school, or get out of the house. Miss Brown handed out whoopings and flushed her grandson’s drugs down the toilet. She scolded Breed when she felt embarrassed about buying groceries with food stamps, telling her granddaughter to hold her head high and focus on survival until the next step.

“Miss Brown was everybody’s mother and everybody’s grandmother in the community,” said Shawn Richard, a neighbor of Breed’s in Plaza East and the city’s first Black cannabis dispensary owner. “We respected that, and [Breed] was raised with values. You know, they had to go to church on Sundays, and the rest of us would go to church with them because Miss Brown demanded that.”

These roots—and a community that saw something in Breed, insulated her and raised her like their own—kept her grounded.

“It was always like, ‘No, you can’t mess with her,’” Breed said about neighbors looking after her. “People in this community, when there was someone with potential, this community was very protective.”

Chapter II: ‘A Raw Ball of Talent’

“My political life had always been about seeking first-round draft choices. London, in that case, was a first-round draft choice. Period.”

— Willie Brown, former mayor of San Francisco

From an early age, Breed caught the attention of mentors, including Gloria Davis, a political activist who championed low-income students of color, and Minyon McGriff, an administrator for the Family School, a Western Addition nonprofit that assists impoverished families.

Breed was rough around the edges but showed promise, excelling in school, playing in the band and participating in student government. She also had an innate ability to connect with people.

“She has jokes. She’s funny,” Richard said. “Her second career would have been a professional comedian.”

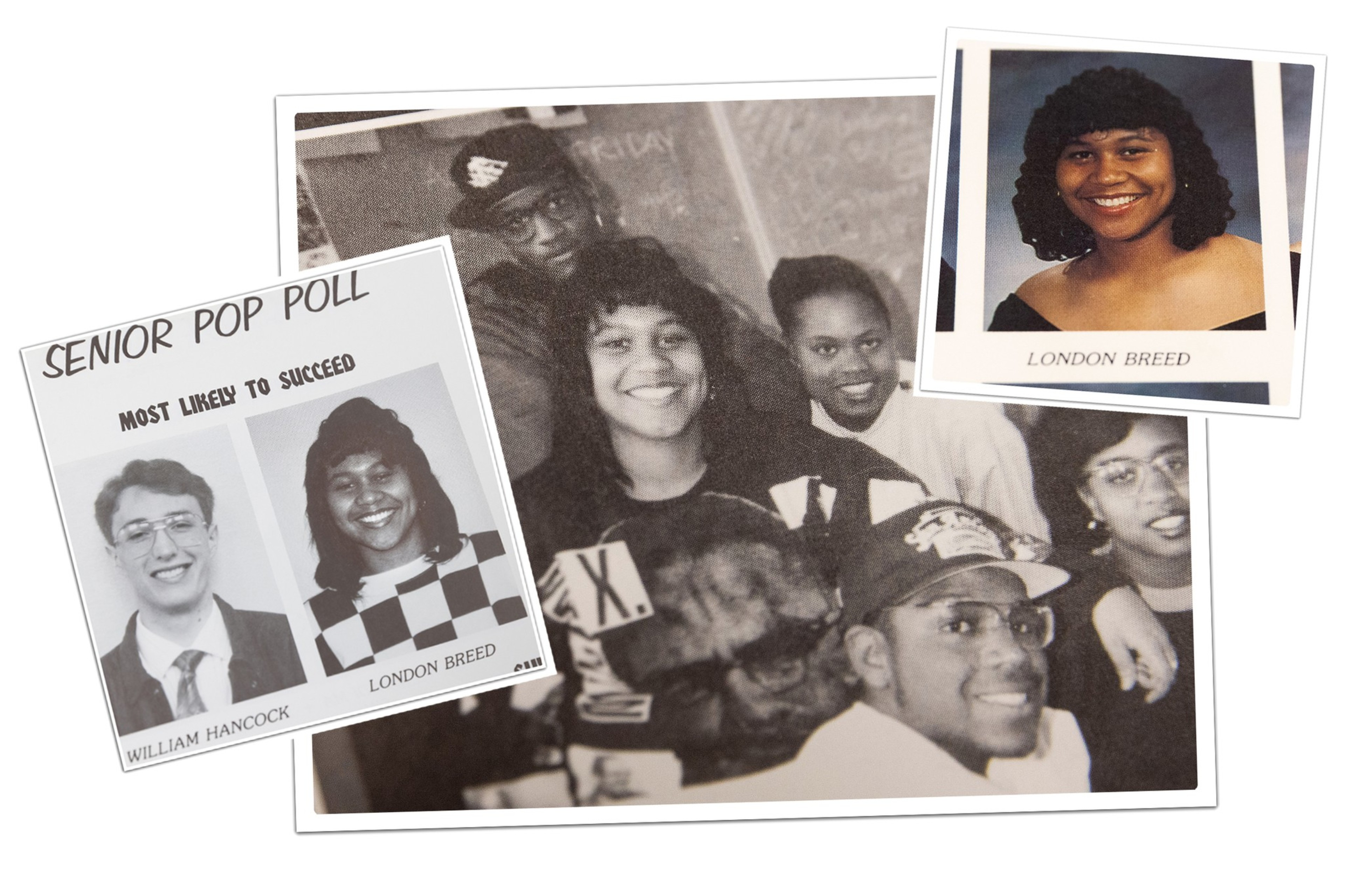

At Galileo High, Breed served as the girls’ vice president of her senior class and was voted “most likely to succeed,” graduating with honors in 1992. One of her after-school haunts was Marcus Books on Fillmore Street—the oldest Black bookstore in the country (opens in new tab) until its closure in 2014—but Breed wasn’t just a bookworm.

“I stayed out late and got in trouble,” she said with a laugh. “But I didn’t do anything that crossed the line.”

She considered attending Spelman College, a historic Black women’s college in Atlanta, but chose to enroll at the University of California, Davis to stay close to her ailing grandmother, who had dementia in her later years. Breed initially majored in chemistry but switched to political science after two summer internships at the Lawrence Livermore National Lab.

“I would never imagine her being a scientist, to be honest,” said Bettie Grinnell, a secretary at Galileo High for the last 50 years. “I mean, she just seemed to have too much energy and people skills for that.”

While still in college, Breed worked on Willie Brown’s 1995 campaign for mayor, helping the former speaker of the California Assembly—no relation to her grandmother—edge out incumbent Frank Jordan. She later interned in the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Neighborhood Services, getting her first taste for power by giving marching orders to departments under the authority of the Mayor’s Office, such as when a pothole needed fixing.

Breed babysat and cleaned houses throughout her time at UC Davis. She planned to head back to San Francisco after college but hadn’t yet mapped out a career.

“I just didn’t want to be poor,” Breed said about her ambitions after college. “And I felt frustrated that my grandmother had to struggle so much.”

In 1999, two years after Breed graduated from UC Davis—whose business school now teaches a leadership course on her life and career—Brown helped place her in a job with the Treasure Island Development Authority.

“I was interviewing some assistants, and a young London Breed came bounding through the door with that 1,000-watt smile,” said Annemarie Conroy, a former San Francisco supervisor who now works as a federal attorney. “She was a raw ball of talent.”

Breed was soon promoted to secretary of the Treasure Island authority, which helped her form stronger connections at City Hall. In 2002, as Brown was in his second term as mayor, he orchestrated Breed’s takeover of the African American Art and Culture Complex, a nonprofit in the Western Addition.

With no expectation of seeking elected office again, Brown shifted some of his leftover campaign money to the nonprofit to give Breed a running start. By all accounts, she took the baton and never looked back.

Over the next decade, Breed not only rescued the African American Art and Culture Complex—renovating the facility and establishing a pipeline of funding from City Hall—but she also came up with numerous programs to keep kids busy and safe. She paid teenagers so they wouldn’t resort to street crimes—an idea that would later be replicated at City Hall (opens in new tab) during Breed’s time as mayor—and one summer, she forced the boys to learn how to ballroom dance.

It’s hardly an exaggeration to say Breed can’t walk more than two blocks in San Francisco without bumping into someone she knows.

“All these people were instrumental in giving her the support she needed from a bureaucratic space,” Sheryl Davis said. “But she knew the community.”

Chapter III: ‘They Don’t Fucking Control Me’

“Willie Brown didn’t wipe my ass when I was a baby — my grandmother took care of me. … I don’t do what no motherfucking body tells me to do.”

— London Breed, mayor

By the beginning of 2012, Breed felt her time had arrived to make the leap into political office. She had paid her dues, serving on the Redevelopment Agency commission and receiving an appointment from then-Mayor Gavin Newsom to serve on the Fire Commission. She’d also gone back to school to earn a master’s degree in public administration from the University of San Francisco.

But when it came time for Lee to appoint a replacement on the Board of Supervisors for Ross Mirkarimi, who had been elected sheriff, he bypassed Breed for Christina Olague, the preferred choice of Chinatown organizer Rose Pak. Breed was incredulous and decided to run anyway, emphasizing her decade-plus in the community fighting the demolition of public housing, mentoring young people and working with police to improve public safety.

Even though Willie Brown did not endorse her, some of his close associates donated to Breed’s campaign. Chatter about Breed was growing louder: She was “Willie’s girl.”

San Francisco voters grew tired of the machine politics that proliferated during Brown’s tenure and embraced multiple changes to weaken the city’s “strong mayor” system, adopting district races for supervisor, public campaign financing and supervisorial appointments for commissions. By the 2012 supervisors race, any hint that Brown—eight years removed from office—might still be pulling strings from afar was met with fierce resistance.

Following a candidate forum at the Harvey Milk Democratic Club, a local reporter asked Breed about her support from Brown’s friends. She hit back.

“You think I give a fuck about a Willie Brown at the end of the day when it comes to my community and the shit that people like Rose Pak and Willie Brown continue to do and try to control things,” Breed said in the now-infamous interview (opens in new tab). “They don’t fucking control me.”

Afterward, Sen. Dianne Feinstein—who, like Breed, unexpectedly became the city’s top official in 1978 after the assassinations of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk (opens in new tab)—yanked her endorsement. Breed called Brown’s spokesperson, thinking she had just flushed her candidacy down the drain.

“I laughed my ass off,” Brown said when recalling Breed’s statements. “But I knew she was going to have to live with it. And that’s a great punishment!”

If anything, Breed’s words solidified her reputation as a brash public figure who wasn’t for sale. Three months later, Breed trounced Olague and six other candidates to take the District 5 supervisor seat.

“I think the best part of that was she grew and she matured,” said John Konstin Sr., a close friend of Breed’s and the owner of John’s Grill. “She realized what politics is all about, and she came out a champion.”

Breed retained her street-fighter edge as a supervisor—she notably took a three-year break from Twitter (opens in new tab) after butting heads with cyclists and critical constituents who dared to step into her replies—but by 2015, she had won the trust of her colleagues and was elected president of the Board of Supervisors.

That trust would not last.

Chapter IV: Knives Out

“I hate to say it. I wish it weren’t so, but those white men are so enthusiastically supporting your candidacy, London Breed.”

— Hillary Ronen, District 9 supervisor

Seven weeks after Lee’s death, the Board of Supervisors held a vote on Jan. 23, 2018, to determine who should serve as interim mayor until a special election in the summer.

Many expected Breed’s confirmation to be a formality. During her time as a supervisor, Breed had proven to be an effective voice for her community, such as when she successfully argued for neighborhood residents to receive preference on federally funded public housing (opens in new tab). She had served as board president for nearly three years before Lee’s death elevated her to acting mayor.

Supervisor Hillary Ronen, a white progressive representing the Mission, had other plans.

During the board’s discussion, Ronen delivered a theatrical speech and suggested Breed was under the control of venture capitalist Ron Conway and other “white, rich men, billionaires” who were supporting her. Breed was forced to leave the board chambers as her colleagues deliberated. By the time she returned, seven supervisors had voted to appoint Mark Farrell—a rich, white man representing the Marina, and a venture capitalist no less—with no acknowledgment of the irony in Ronen’s tearful performance.

Boos rained down from members of the Black community sitting in the gallery and the meeting was forced to recess amid shouts.

“I think this is what probably bothers me the most about some elected leaders,” Breed said. “They want to talk about diversity. They want to talk about poor people. They want to talk about the challenges that people are facing and all these needs. And they have never lived like I’ve lived.”

Breed knuckled up after the public embarrassment, reframing the snub into a powerful talking point on what happens when a Black woman challenges the status quo. In several months, she built a campaign for mayor that brought together a moderate coalition to defeat two opponents, former Supervisor Jane Kim and Mark Leno, a former supervisor and state legislator.

“It was in that moment—that grace under fire, that strength that she showed [during the board vote], that got her elected mayor,” said Conor Johnston, a former Breed staffer.

Breed has carved out a lane as a centrist in the city’s overwhelmingly liberal political landscape, backing business interests while taking up the mantle of social justice causes. She also talks tough on the need to prosecute drug dealers, place users in treatment or behind bars and force people with severe mental illness into conservatorships.

It’s a balancing act, and the mayor bristles at accusations about not caring for low-income communities of color, especially from white progressives like Ronen and Supervisor Dean Preston, one of the wealthiest members of the Board of Supervisors. Preston, who did not respond to a request for comment for this story, has been a frequent Breed critic after challenging and losing to her in a 2016 supervisor race.

“I wish [Preston] would spend more time focusing on taking care of the residents of his district who are constantly frustrated over various situations, so they turn to me and have no relationship with their supervisor,” Breed said. “It’s sad.”

Chapter V: What Would Beyoncé Do?

“They used a term which always bothered me, which was the ‘city family.’ On the one hand, the notion of a family is supportive of one another, which is part of what they meant. On another hand, it was also like the mob.”

— Aaron Peskin, District 3 supervisor

The mayor gained international acclaim early in the pandemic when she shut down San Francisco before any other city in the United States. Breed’s announcement showed cunning—she jumped in front of other Bay Area counties and stole the spotlight. There was no way in hell the mayor was going to let a bunch of lab coats be the face of the most consequential public health order in a century.

A placard on Breed’s desk asks: “What would Beyoncé do?”

The city’s ban on public gatherings and a swift rollout of testing and vaccinations made it a positive outlier: San Francisco’s rate of Covid deaths is among the lowest of any major city. Aside from a maskless slip-up at the Black Cat jazz club—where Breed unrepentantly enjoyed the timeless sounds of Tony! Toni! Toné! (opens in new tab)—the mayor scored high marks for her handling of the pandemic. And in a little serendipity, the all-consuming focus on the pandemic distracted from a festering scandal.

On Valentine’s Day 2020, a month before the Covid shutdown, Breed wrote a blog post (opens in new tab) in which she admitted to a long-ago romantic relationship with the head of the city’s Department of Public Works, Mohammed Nuru, who had been arrested a month earlier by the FBI for a long-running scheme of bribes and kickbacks. The relationship had ended two decades prior, she wrote, but their friendship had continued over the years.

Nuru had covered thousands of dollars in car bills, Breed wrote. The top-paid mayor in the country—earning an annual salary above $350,000—never reported the 2019 expenses as a gift, she said, because she considered Nuru a longtime friend.

He later received a prison sentence of seven years and the city’s Ethics Commission levied a fine on Breed (opens in new tab). The scandal made the mayor more guarded, a close associate said.

“When you come through life and your political career, where you’re kind of let down or betrayed by a lot of people throughout, it’s hard to trust people,” a former staffer in the Mayor’s Office said. “You’re going to be careful about who you let into your inner circle.”

Though Breed is down-to-earth and gets out of the office—she still rides Muni, grabs drinks and dinner with friends, strolls around street fairs and takes in shows at Cobb’s Comedy Club—she’s also protective of her personal life. Over the last year, Breed has been photographed at events with Dustin Sharpe, a hip-hop artist (opens in new tab) originally from South Africa. Sources close to the mayor confirmed they are in a relationship.

Asked whether the two are an item, Breed demurred. “Now you gotta get into my personal business,” she said with a smirk, declining to talk about Sharpe or her opinion of his music.

Chapter VI: A Sister’s Love

“Nobody could mess with me, because I was Sonny Boy’s sister, you know?”

— London Breed, mayor

Napoleon Brown was a hustler in the Western Addition and a member of the Outta Control Posse, a gang that ran the Plaza East projects, which was known as the O.C. for short. Nicknamed “Sunnyboy,” Brown eventually went from slanging drugs to doing them himself.

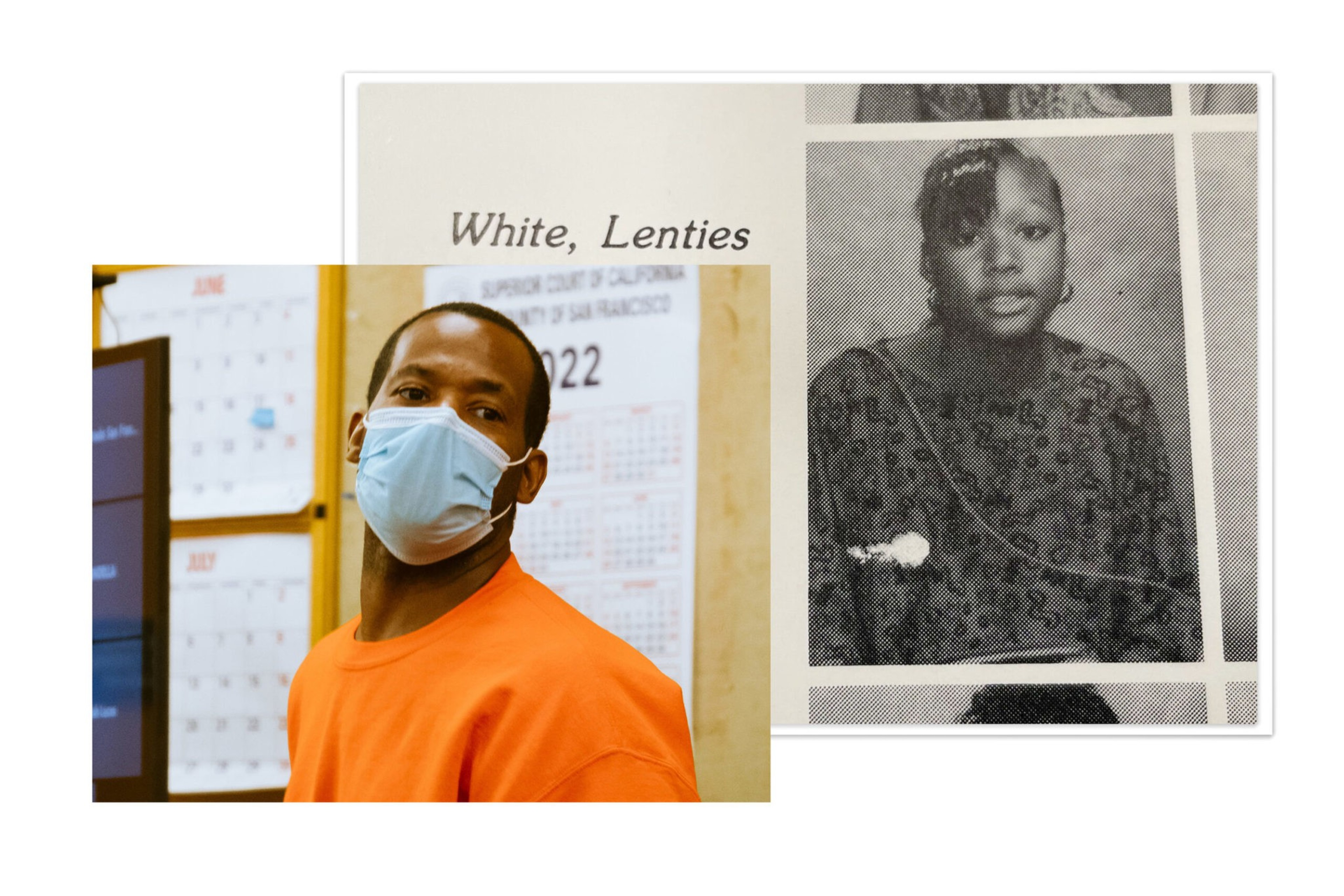

In June 2000, Brown was accused of orchestrating a robbery of a Johnny Rockets diner in the Marina. Lenties White, a 25-year-old mother of two who had attended the same high school as Breed, drove the getaway car. For reasons that still remain in dispute, White got out of the vehicle on the Golden Gate Bridge and was struck by a drunk driver.

It’s unclear if Brown forced White out of the vehicle, but police on the scene said White used her dying breaths to identify her killer with the initials of his nickname: S.B.

Breed and others testified that Brown never went by these initials, but prosecutors secured a murder conviction that has kept him behind bars for more than two decades. A second trial and negotiations with prosecutors eventually reduced Brown’s conviction to manslaughter.

In her first year as mayor, Breed used her official title as mayor in a letter asking then-Gov. Jerry Brown to grant her brother an early release from prison. The city’s Ethics Commission found this action to be an abuse of power, also dinging her for the unreported gifts Nuru gave her and a separate campaign violation. Breed agreed to pay almost $23,000 in fines, ranking among the city’s highest ethics penalties in recent history.

The mayor continues to push for her brother’s release, and a change in state law has set up a much-anticipated resentencing hearing next month. It’s possible Brown could be freed this year.

Breed, testifying in the original case, told prosecutors she saw her brother sleeping on her grandmother’s couch around midnight, which was roughly the same time as the robbery. For White’s mother, Sandra McNeil, the potential alibi raised questions about whether the mayor might have committed perjury in an attempt to help her brother.

McNeil told The Standard she believes the mayor lied but has no animosity toward her. The families know each other well, having lived close to each other in the Western Addition. But the idea of Breed’s brother walking free back in the neighborhood doesn’t sit right.

“Being around somebody who killed my daughter? No, I don’t want to walk the same streets as him,” McNeil said.

And yet there are no hard feelings for McNeil, who said her Bayview beauty salon received funding through the mayor’s Dream Keeper Initiative, a historic investment in the city’s Black community. The program received $120 million in funding to start and Breed annualized $60 million in city funds to go to nonprofits and small businesses.

“She’s done her job,” McNeil said. “I would vote for her again.”

Chapter VII: ‘We Have To Get Out of Our Own Way’

“I felt like she was ready to help lead our city and stood by her. But, ultimately, she hasn’t risen to the moment and the crisis.”

— Ahsha Safaí, District 11 supervisor

In early November 2021, a group of immigrant families in the Tenderloin—the epicenter of the city’s drug trade—led a march to City Hall to demand the mayor take action on rising violence in the neighborhood. A few weeks later, a flash mob of vandals stormed luxury retailers in Union Square, ransacking more than $1 million in goods. Cable news networks ran around-the-clock coverage showing San Francisco’s brazen crime spree.

Finding herself squarely in the hot seat, Breed was fed up and had no intention of hiding it. The week before Christmas, the mayor held a fiery press conference, declaring an emergency in the Tenderloin and saying it was time to put an end to “all the bullshit that has destroyed our city.”

Breed announced plans for a drug treatment referral center in the Tenderloin, but the rollout was ramshackle. Journalists were barred from entering the center, which helped city officials conceal the fact that a shortage of shelter beds and client services had turned the Tenderloin Linkage Center into a de facto “safe” drug consumption site. The international press ran wild with stories about a city-funded facility that allowed addicts to “shoot up, pass out and scatter their needles” (opens in new tab) before turning people loose to die on the streets.

“Once she announced her Tenderloin Linkage Center emergency declaration, we sat there and spent multiple meetings talking about what the plan was,” said Supervisor Ahsha Safaí, the first major candidate to declare he’s running against Breed in next year’s election. “Ultimately, we never got those answers. It transitioned into a place that I think became a magnet for crime and drug use and drug-dealing.”

The mayor’s handling of the pandemic revealed what the city can accomplish when elected officials and public agencies work together in one direction. That same sense of urgency and discipline has yet to materialize in the city’s drug crisis.

Breed’s appointment of Brooke Jenkins as district attorney last summer, following the recall of progressive prosecutor Chesa Boudin, finally got the Mayor’s Office, police and the city’s criminal justice system on the same page in aggressively charging drug dealers and even arresting users—although the Board of Supervisors remains divided on the strategy. This month, the mayor announced plans for a command center to coordinate state and federal law enforcement resources to make a dent in the drug markets, but it’s too soon to say whether those efforts will be successful.

“We’ve been in a state in San Francisco where there has been political paralysis,” Jenkins said. “[Supervisors] have been obstinate every time something is attempted by the mayor.”

Across the political spectrum, there is broad agreement that San Francisco’s many crises weren’t created overnight. The city’s infamously sprawling bureaucracy, which includes dozens of departments along with 130 commissions and advisory bodies (opens in new tab), would be difficult for any executive to wrangle. San Francisco’s byzantine rules and planning codes, long tinkered with through ordinances and ballot measures, complicate everything from building homes and paying taxes to starting new businesses.

“We have to get out of our own way,” Breed said. “It’s like the death of a thousand cuts.”

Chapter VIII: Nothing To Lose

“I’m a fighter, and I’m a beast when it comes to trying to get what I want.”

— London Breed, mayor

The mayor’s closest allies say Breed’s sole focus has always been about San Francisco and her interest in ascending the political ladder to statewide office or Congress has lessened, leaving her legacy dependent on winning a second term.

But many of these same supporters have raised the question of whether any mayor could effectively lead San Francisco under the current circumstances.

To achieve her goals and cut through the Gordian knot of red tape, bureaucracy and political gamesmanship, Breed told The Standard she needs an expansion of powers. She noted the emergency authorizations she had during the pandemic, which allowed her to bypass certain processes and helped her administration decrease unsheltered homelessness in the city by 15% (opens in new tab).

“No matter who the mayor is, they will not be as effective as the public wants to see any mayor be without the ability and flexibility to make hard decisions,” Breed said.

Breed has limits on her ability to hire most department heads, as commissions often submit candidates for her approval; supervisors can also reject the mayor’s commission appointments. The constant tug-of-war between Breed and the board over the city’s commissions—some of which have real power over policy—came to a head last year when a police commissioner outed the mayor’s practice of having her appointees submit undated resignation letters.

It appears likely the mayor and her supporters will put forward a ballot measure next year to reform the City Charter and strengthen the powers of her office. But if Breed’s popularity continues to fall, the idea of handing her more power could be a tough sell with voters.

“If we’re going to hold the mayor accountable—as we always should, no matter who the mayor is—we damn well better give her the ability to actually run an executive branch,” said state Sen. Scott Wiener.

Breed’s progressive adversaries on the Board of Supervisors, who until this year had a rock-solid majority on most votes, have scoffed at the idea that the mayor doesn’t have the tools to succeed.

Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who serves as board president and is rumored to be considering a run for mayor, said the problems lie more with Breed’s temperament and inability to compromise. Multiple elected officials said the mayor consistently begins one-on-one meetings by berating them for extended periods.

“Look, in real life, people don’t like to be shit on and belittled and humiliated,” said Peskin, who unleashed his own alcohol-fueled tirades (opens in new tab) on city staff before going to rehab. “Politics is the art of the possible, which means rather than doing this ‘us versus them,’ reach across the aisle.’”

The mayor disputed Peskin’s account of not working collaboratively.

“Even if I get loud in a meeting, I’m not yelling at you—I’m talking to you,” she said. “I get emotional. I get excited. You know, my personality is such that sometimes people who are not Black people don’t take it the right way. But it’s not for lack of trying to collaborate to deliver for the people.”

Breed’s broader goals appear to be in sync with what a majority of San Franciscans want: a clean, safe, vibrant city. The lack of a truly threatening challenger has many political observers thinking Breed will secure a second term despite her low poll numbers.

“It’s very hard for me to imagine London not easily winning reelection,” said Jane Kim, who took over the Working Families political party after her 2018 mayoral defeat.

The coming months will prove pivotal in whether voters remain patient enough to give Breed another term.

More high-profile businesses fleeing the city would rattle confidence in the mayor and her new economic development chief, Sarah Dennis-Phillips. Breed enlisted the California Highway Patrol and California National Guard to help fight the drug crisis, and residents expect visible progress on drugs and crime—and fast. Pressure will likely reach its peak by November, when President Joe Biden and other heads of state will descend upon the city for the closely watched Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation leaders’ summit.

Just one or two high-profile screw-ups could validate the murmurs of doubt about Breed.

While the mayor’s strongest supporters outside of City Hall continue to back her in public, multiple sources told The Standard that there is no guarantee they will throw their weight behind her reelection in 2024.

“We’re going to see what happens with the city between now and [the election], who decides to run,” said Sachin Agarwal, co-founder of the political group GrowSF, which spent more than $850,000 last year on ballot measures while supporting moderate supervisor candidates. “We’re going to pick the right person for the job.”

On a sunny afternoon last month, a crowd gathered at United Nations Plaza to hear the mayor defend her efforts to tackle the deadly drug overdose crisis. Breed ticked off the programs, services and money San Francisco has thrown at its problems, and she admitted it isn’t enough. She admitted her best might not be enough.

“I am doing this job without fear of losing it because, at the end of the day, when you know what it feels like to grow up in chaos, you want nothing more than change,” Breed said. “Some people are going to like it, and some people aren’t, and that’s just what it is. Because I’m putting everything on the line to change what we need to do.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to note that Mayor London Breed inappropriately used her official title in a personal letter to the governor seeking her brother’s release from prison.