In a city known for its ballooning price tags on everything from real estate to retail, the Mechanics’ Institute (opens in new tab), a literary oasis in the heart of Downtown, might be the very best deal in town.

For a mere $120 a year—$10 a month—members get access to a lending library, workspace with WiFi and a calendar filled with a range of five to 15 events each week, many of which have free food and drink.

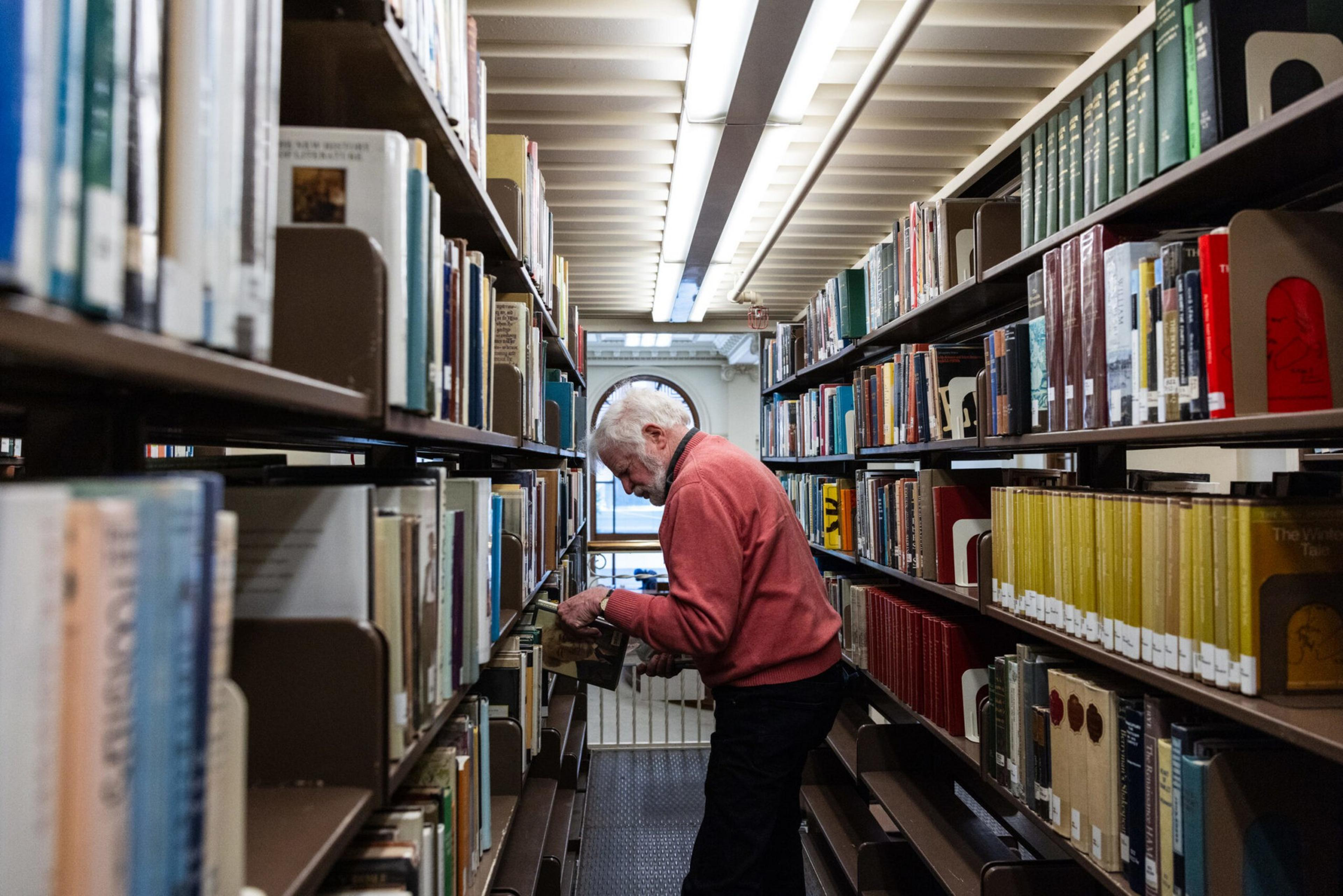

“It’s way cheaper than any coworking space,” said freelance software developer Keegan Leary, who has been a member of the institute for two years. He likes walking the stacks and breaking up his work-from-home routine by being around other people.

“It’s a hidden gem,” Leary said. “I love the old-timey feel.”

Rudi Miller agreed. On a recent Wednesday, the former New Yorker and University of California Berkeley law student was trying out the space for the first time—but she already knew she was going to join.

“Other coworking spaces are too loud and too expensive,” she said. “I like the quiet here, and the events look fun.”

Yet despite the appeal, most people don’t even know the Mechanics’ Institute exists—or exactly what it is.

On a recent public tour—which happen every Wednesday at noon—of the historic nine-story building, more than half hadn’t known it existed, despite living in San Francisco their entire lives, according to Alyssa Stone, senior director of programs and community engagement.

“We are a hidden-hidden gem,” Stone said.

The treasure behind the doors at 57 Post St. is about much more than affordability, though. And while the concept of a members-only library might seem exclusive, it’s baked into the more than a century-and-a-half-old mission of the Mechanics’ Institute to be accessible to all.

Open to All, Always

When the Mechanics’ Institute opened in 1854, a mechanic wasn’t someone with their head under the hood of a car.

“The word mechanic in the 19th century was used very generally to describe people who made things,” said Taryn Edwards, a former librarian at the institute who worked there for over 15 years. “You could be a butcher, a baker, a candlestick maker and be considered a mechanic.”

Founded in the Tax Assessor’s Office in the city of San Francisco because it was a nonreligious, apolitical space, the Mechanics’ Institute was meant to be an institution of learning and training.

“From our earliest years, there have been no barriers to joining,” Stone said. “Anyone could become a member, regardless of immigration, race, ethnicity, gender, age, financial background, familial background. Even from our earliest days, women were always welcome.”

It was unusual at the time, when many clubs and memberships—like the Bohemian Club, the Olympic Club and the Family Club—were open only to men and remain so today (the San Francisco Italian American Club is also exclusive to men).

The organization was part of a larger social movement, a response to the Industrial Revolution, which aimed to improve the livelihood and rights of the working class. There were some 800 Mechanics’ Institutes in England alone in 1854, the year the San Francisco branch was founded.

Run as independent entities, there were handbooks available at the time with instructions on how to set up your own Mechanics’ Institute.

Typically the institutes had three components: a library, a lecture hall and a game room—for the San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute, that game has always been chess. While many such institutes have since shut down or been transformed into entities with different names, our own Gold Rush-era branch is going strong, despite going through numerous upheavals—including being burned to the ground.

“Our mission is to serve writers, chess players, readers, thinkers, the curious, film lovers,” Stone said. “We’re here for people’s interests and to be able to provide them with information.”

A Hidden Bounty

The people who do know about the Mechanics’ Institute duck in to take photos of its spiral staircase—what very well might be the most Instagrammed set of stairs in all of San Francisco.

The undulating staircase is the tallest in the nation, according to Stone, and it was fabricated on the East Coast before the building’s opening in 1910 and then shipped around Cape Horn to be assembled at the library.

“The staircase is very, very popular stuff on our tours,” Stone said.

The metal grate on the spiral staircase has an image that repeats throughout the institute: a key that symbolizes the unlocking of knowledge. What looks like a square-shaped lollipop, the motif is repeated on tile floors and hanging lamps.

The institute’s knowledge to be unlocked is not only in books but also in recreation—namely, chess. The building houses the oldest (opens in new tab) continuously operating chess club in the nation. When Vinay Bhat achieved grandmaster status in 2008, he was the youngest person ever to hold the title—and he learned to play chess at the Mechanics’ Institute.

Bhat recently returned to the institute for the release of his book, How I Became a Chess Grandmaster, which is filled with pictures of him playing chess at the Mechanics’ Institute.

The event also included the “Summer Blitz” tournament; the room was packed with chess players, including two grandmasters.

Other jewels of the institute include an 1853 survey map of San Francisco that survived the fire of 1906. It’s one of only a handful to exist in the world, and it now hangs on the second floor.

“The only reason it survived is because it was in a safe,” Stone said. “Everything else around it was destroyed.”

The building also has offices for rent (opens in new tab). Literary magazine Zyzzyva (opens in new tab) has its offices there, along with several lawyers and doctors, and an organization called the International Wizard of Oz Club (opens in new tab).

“I can’t imagine a better place to have an office,” Stone said. “These beautiful high ceilings with huge windows that look out across the city.”

The More Things Change

Given that the organization has been through its fair share of struggles in its century-and-a-half history, the Mechanics’ Institute may have a lesson for us—and for Downtown San Francisco.

A climate of fear took over Downtown San Francisco in 1856, after the murder of the publisher James King of William, who was killed by James Casey, a member of the Board of Supervisors. The killing resulted in the formation of the second Vigilance Committee in San Francisco.

“This was no joke; people moved out of the city because of this,” Edwards said. “Namely Mechanics’ Institute President Roderick Matheson, who was concerned about raising his kids in such a violent environment.”

In what could have been a story ripped from today, Matheson moved out of town—to Healdsburg.

The fire after the 1906 Great Earthquake burned the original institute to the ground, but the library came back bigger and better, in part by buying materials the city would need—like books on engineering and masonry—for the massive rebuilding effort.

“That is how we pulled ourselves up by our bootstraps,” Edwards said. “With the aim of helping the city with the rebuilding effort.”

During the Great Influenza of 1918, the institute closed for only couple of days—our present-day pandemic was much more catastrophic. World War II was another difficult time in the institute’s history.

“There were limits on nighttime activities because of fear over air raids,” Edwards said, and staff and clientele were drafted to fight in the war.

With big-name retailers pulling out of Downtown, acres of empty office space and deteriorating safety conditions Downtown, will the Mechanics’ Institute—located just a stone’s throw from the Montgomery Street BART Station—be able to survive this latest downturn? It’s hard not to wonder, especially in light of the recent departure of the organization’s CEO. But just like San Francisco’s phoenix rising from the dust, the organization has been through boom-and-bust cycles before.

“We are here to serve the community,” Stone said when asked about the organization’s future. “And we will continue to serve the community.”