San Francisco’s public school staff just started their third school year with a faulty payroll system, and the district is still slogging through a backlog of 3,000 issues (opens in new tab).

Last month, almost 1,000 public school employees received their paychecks days late (opens in new tab).

For employees of the San Francisco Unified School District, a mundane-sounding glitch in a payroll system that went live in January 2022 brought real-world consequences, including canceled insurance benefits during health emergencies, tax-filing nightmares and delayed retirement contributions. Some school district staff even had to borrow money to pay their rent.

The district has spent more than $40 million on the system—called EMPowerSF, configured using software by SAP America—and says progress has been made. But the leader of the United Educators of San Francisco union wants the district to pull the plug.

“This system’s gotta go,” said the union’s president, Cassondra Curiel. “There’s only so long you can squeeze a round peg in a square hole.”

The district adopted EMPowerSF with high hopes for replacing an antiquated, 17-year-old system that was paper-heavy and tracked its $1 billion budget on Google Sheets (opens in new tab). It contracted with SAP America in 2018 and, later, its subsidiary, SAP Public Services.

The school district selected SAP, even though problems linked to the company’s payroll software had made headlines in other jurisdictions. The best-known instance came in 2016 when the software company settled with the California State Controller’s Office (opens in new tab) for $59 million after an exchange of lawsuits.

So why did San Francisco school officials still choose SAP? And will they pull the plug, too?

‘I Don’t See It Getting Better’

Although it’s the namesake behind the SAP Center, home to the National Hockey League’s San Jose Sharks, German-founded SAP—originally called System Analysis Program Development—is hardly an instantly recognizable corporation like, say, Oracle or AT&T. In the world of California government, SAP is rather infamous.

The company’s connections to payroll snafus are extensive. In 2005, Los Angeles Community College District officials called a troubled transition to a SAP-powered system (opens in new tab) “horrific” after reports of missing pay. Two years later, a new $95 million payroll system held up by SAP software left thousands of Los Angeles Unified School District employees without checks (opens in new tab). That episode took about a year to stabilize, and SAP remains in use there today.

In 2010, Marin County stopped (opens in new tab) a $30 million SAP project, leading to a legal battle with the implementation contractor (opens in new tab), Deloitte. The same year, the State Controller’s Office hired SAP for what was then billed as the largest payroll modernization project in the country. In 2013, it ended its $90 million contract with the software company after the project’s pilot stage became overwhelmed with errors.

The ordeal was so colossal that it was the subject of a 2013 California Legislature report (opens in new tab), which highlighted lapses in due diligence and disagreements about contractual responsibilities. The settlement stemming from another legal battle, which granted $59 million to the state with no admission of fault for either party, came one year before San Francisco school officials sought contractors for a new payroll system in 2017.

“Every time SAP is implemented, it seems to fail,” said Bilal Mahmood, an entrepreneur and 2022 Assembly District 17 candidate who analyzed San Francisco’s implementation errors (opens in new tab). “The legacy companies—the SAPs, the Oracles—they know how to navigate the government procurement process.”

As the 2013 state report shows, the Controller’s Office ordeal led to questions about how well software like SAP’s can work for public entities with numerous departments and labor agreements. But a payroll transition’s success also comes down to preparation and management.

“SAP has a long and successful track record of partnering with thousands of public sector organizations including the San Francisco Unified School District,” the company said in a statement. “We are fully committed to ensuring our customers realize the value of their digital investments, and in this case more specifically, the long term sustainability and success of the SFUSD.”

The decision-making process is somewhat opaque. A public records request conducted by The Standard did not yield any documentation indicating how the district came to pick SAP out of a pile of software companies from the 2017 public contract proposal process. It is unclear how many bids were made, which was the cheapest or whether SAP had addressed recent issues with transitions.

A district spokesperson did not respond to questions regarding EMPowerSF’s origins and future.

The district’s Service Employees International Union chapter, whose president has called the new system “the worst thing to come to the district,” is similarly in the dark, despite repeated questions about why the school district chose this particular system. And though union leaders acknowledge that the decision to bring in expensive consultants—now costing over $15 million—has greatly improved the situation, they don’t see a great future for workers when it comes to EMPowerSF.

“I don’t have any faith this program is going to get any better,” said Antonae Robertson, the chapter’s vice president. “I don’t see it getting worse, but I don’t see it getting better.”

Many technical aspects of the contracts were written to the district’s disadvantage, according to a Standard analysis. For example, Infosys, the information technology firm that was hired to put the software into action, did not have a contractual responsibility to remedy issues with the system. The district was also responsible for migrating data between the old system and the new.

Mahmood stressed that he has great empathy for government entities changing payroll systems, as software must be customized to account for all their intricacies. The problem compounds for districts like San Francisco that reported gaps in documentation needed to plug into the payroll system, he added.

After combing through the district’s contracts, Omid Ghamami, a procurement consulting expert who reviewed the paperwork at the request of The Standard, highlighted another red flag: that the district switched from one major payroll provider to another rather than modernizing the preexisting PeopleSoft system by Oracle.

“I would suspect they blamed these issues on the system rather than their own procedures,” Ghamami said. “When they switched to another system, they got a rude awakening. The worst thing they could do is let history repeat itself.”

Keep or Ditch?

Under Superintendent Matt Wayne, who began his post in July 2022, the district has simplified and addressed many issues with district operations identified as the major causes of its payroll misery. Several key vacancies in business services, technology and human resources departments continue to be filled as the caseload is increasingly tamed.

“We’re in a very different place than we were a year ago,” Wayne said at the Aug. 8 board meeting. “[There’s] a lot of work to do, but there has been progress. You have my continued commitment to make this work for us because we need to focus, as I said, on our [academic] goals—which is what we’re really here for.”

Since 2018, the district has spent at least $43 million across seven contractors to launch the system and clean up the mess, according to a Standard analysis of related records. Of that, SAP accounted for $5.9 million (opens in new tab).

In addition, the district hired another consultant for $2.6 million to stabilize its business operations (opens in new tab), including payroll, through July 2024.

How much longer until EMPowerSF works for the district remains to be seen. The smart move in 2017 would have been to upgrade PeopleSoft, Ghamami said. The smart move now, he added, would probably be to stick with SAP, due to the district’s sunk costs.

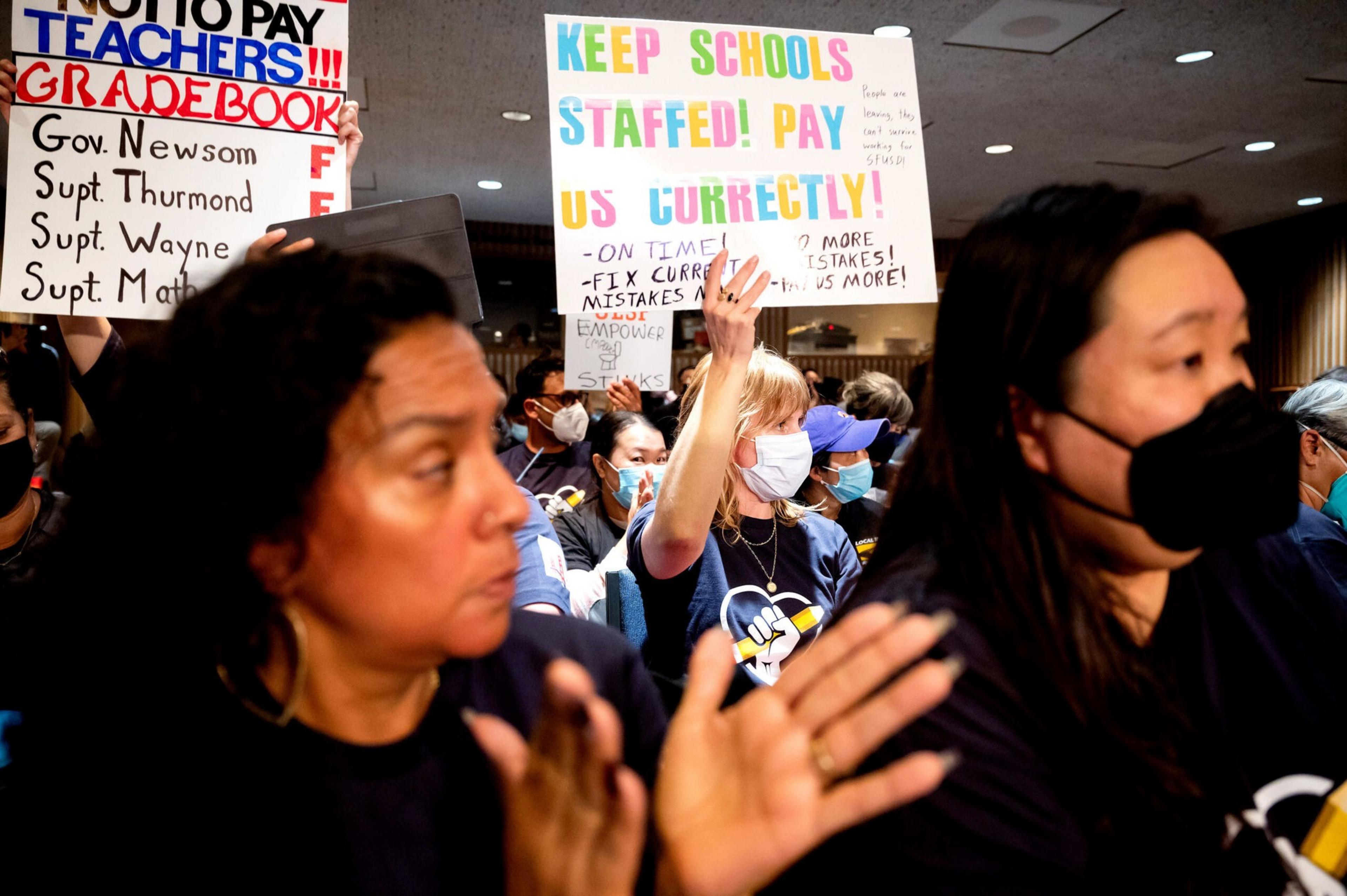

Curiel, the educators’ union president, however, has seen enough. The union staged a takeover of district offices in March 2022 to secure agreements for timely replacement checks and interest for delayed payments, but it’s unclear when the district will be in a place to tally all that up.

Meanwhile, workers still have a tough time understanding their paychecks and what may have gone wrong. An official union complaint is working its way through a state system.

Frank Lara, the union’s vice president, has fielded complaint after complaint from members. This year, he watched his own help ticket move painfully slowly through the system while he was charged an extra $850 a month for health care his family did not receive.

“It just gets lost,” Lara told The Standard. “There’s some key system issues that may not be solvable.”