In the dog days of summer, while many California state legislators were vacationing or raising campaign money during the monthlong recess, Scott Wiener was convening secret meetings. The state senator and a close-knit crew of housing wonks were hatching a plan to make an 11th-hour amendment to one of his bills—one that would surely raise the hackles of some of his fiercest critics.

During his seven years in the Legislature, no elected official in California has proposed more ambitious policies to streamline housing construction than Wiener.

Those efforts have made him loved by YIMBYs, the boisterous “Yes In My Backyard” movement that believes developing both market-rate and affordable housing will reduce costs and demand. But some of those same laws have made Wiener equally loathed by NIMBYs, a less-defined group whose reputation for saying “Not In My Backyard” is rooted in retaining the character of neighborhoods, often leading to accusations of opposing new developments under the pretext of environmental concerns.

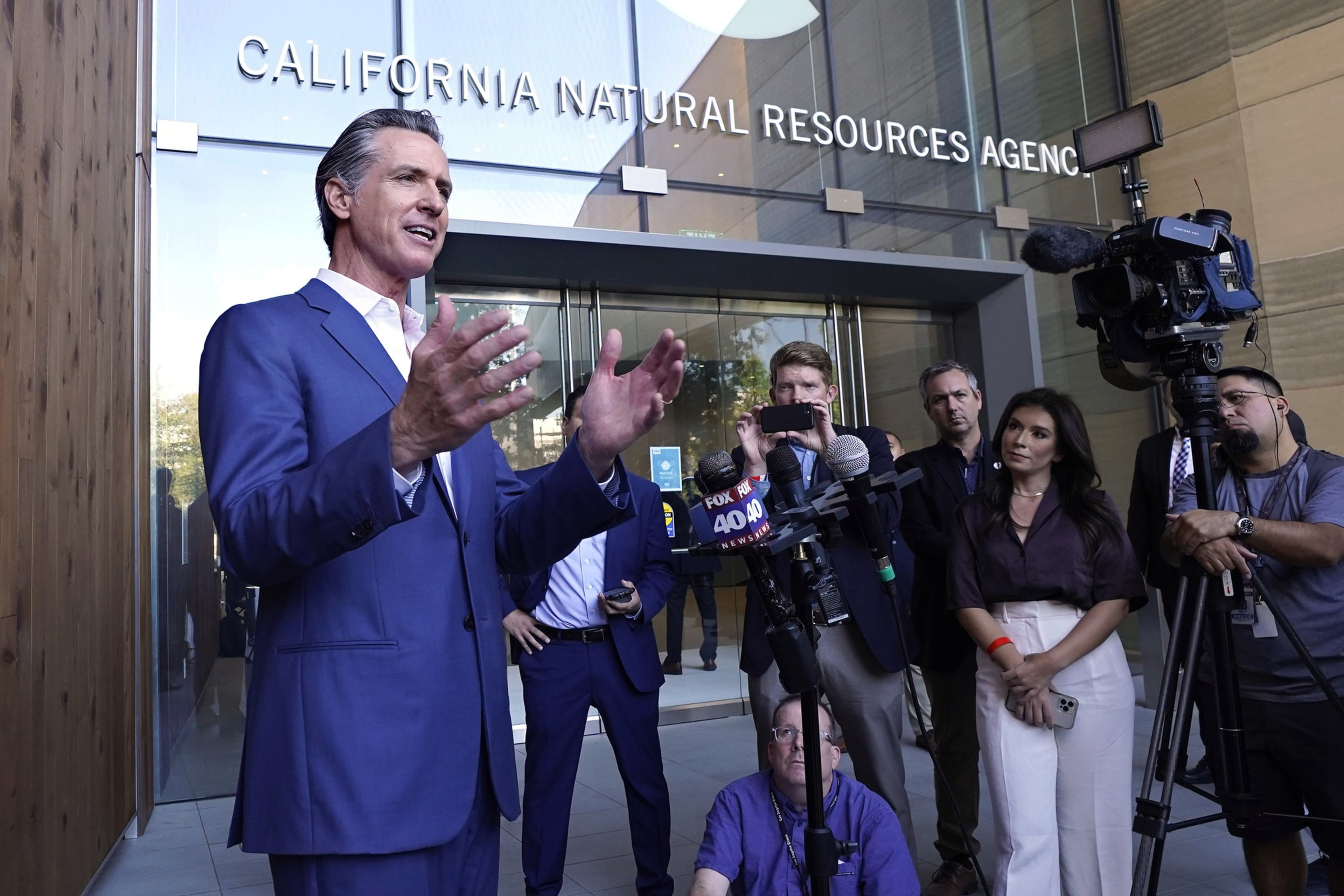

Wiener made his confidantes swear an oath to secrecy in the early August confabs. Any leaks ahead of a final hearing in the California Assembly’s Appropriations Committee would give opponents of his housing bill time to lobby against its passage before making veto pleas to Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“I wasn’t sure, you know, how different people would react,” Wiener told The Standard.

READ MORE: San Francisco Moderate Democrats Want a Clean Sweep of Local Party

As a former San Francisco supervisor, Wiener has had a front-row seat in observing how local control has left housing proposals in the city to languish. The squeeze of high rents and home prices has created a crisis that bleeds over into many of the city’s other issues, in particular homelessness.

Seeing an opportunity to flip San Francisco’s housing inaction on its head, Wiener introduced a late amendment to his bill SB 423 and winced in expectation of impact. The amendment subjects San Francisco to extra state oversight that could eliminate local control next year. But then something strange happened: nothing. No swarm of angry letters and phone calls. No coordinated campaign to lobby the governor.

“At first, we were weirded out,” said Erik Mebust, a spokesperson for Wiener. “Like, is there something we don’t know about? Is there some kind of secret plan here? And that has not materialized. And that is puzzling.”

The silence from NIMBYs before and after Newsom signed SB 423 into law last Wednesday has been deafening, but the reality is now washing over Wiener and his supporters. A decade into the movement, the YIMBYs have outflanked their opponents and taken the upper hand in California’s housing war.

“The tide has been turning for a while,” Wiener said. “It continues to turn.”

Planting the Seeds

Even by California standards, San Francisco has a unique position as a housing pariah. Under the city’s Housing Element, a plan adopted earlier this year, the city is on the hook to allow for 82,000 new housing units by the end of 2031.

However, San Francisco has approved just 1,743 new units for construction this year, according to the city’s Planning Department. The city’s current state-set targets for new construction, known as Regional Housing Needs Allocation goals (opens in new tab)—broken down across four income levels from very low to above moderate—suggest the annual number of approved units needs to be around 10,000.

One reason for this is San Francisco reportedly has the lengthiest building permit process in the state at 627 days (opens in new tab)—roughly 400 days longer than Oakland and 300 days more than Berkeley.

“We’re so many thousands of units behind in housing production that we have to continuously, systematically attack this problem,” said Laura Foote, executive director at YIMBY Action.

Wiener’s prodigious work in this realm included three housing bills (opens in new tab) signed into law this year, including permit exemptions for churches and nonprofit colleges and the creation of a new tax-financing district to replace San Francisco homes lost to “urban renewal.”

“Over the last six, seven years, we have started to build a new structure and a new approach for housing, planting a lot of seeds,” Wiener said. “And I think over time, those seeds will grow and ultimately blossom.”

The amendment Wiener and his cohorts drew up for SB 423—a bill he crafted to reinforce SB 35, landmark housing legislation that has created more than 3,000 units of housing in the city—singles out San Francisco for an annual review of its housing permit goals if it is found to have fallen short. Come 2024, that is all but guaranteed to be the case.

The consequences of SB 423 being signed into law could be massive.

By next summer, a half-century’s worth of planning rules and regulations—splattered together with the unintentional precision of a Jackson Pollock painting—are expected to be pushed aside if housing proposals meet the city’s basic requirements.

“What it does is it removes politics from housing approvals,” said Todd David, a longtime political associate of Wiener’s and one of the leaders of a tech-funded political group called Abundant SF.

As a result, all housing proposals in the city will likely begin receiving a ministerial approval process, meaning any proposal that meets city planning requirements would not be subject to CEQA, the state’s environmental review, or other local objections before receiving a permit within 180 days.

Meanwhile, all other California cities will remain subject to a review every four years for their housing goals.

“This has the potential to dramatically shift how development is reviewed and approved in San Francisco,” said Dan Sider, chief of staff for the city’s Planning Department. “The key word is ‘potential,’ and there is a lot of conversation about how real this may or may not be.”

Wiener said his legislative maneuver was inspired by dwindling housing production numbers and continuing CEQA roadblocks. San Francisco’s inability to approve and build housing—partly because anyone from the public can object, launching lengthy community outreach and input—has made it the only city in California to undergo an unprecedented review by the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

The findings from this review—already finalized but yet to be released, Wiener said—was sparked by the Board of Supervisors’ controversial decision in 2021 to shoot down plans for a 500-unit tower to replace a parking lot on Stevenson Street. One of the more maddening arguments against the project was that the building would cast shadows on neighboring Mint Plaza.

Wiener, Mayor London Breed and many others in San Francisco howled over the board’s decision. But the YIMBYs weren’t done taking their lumps.

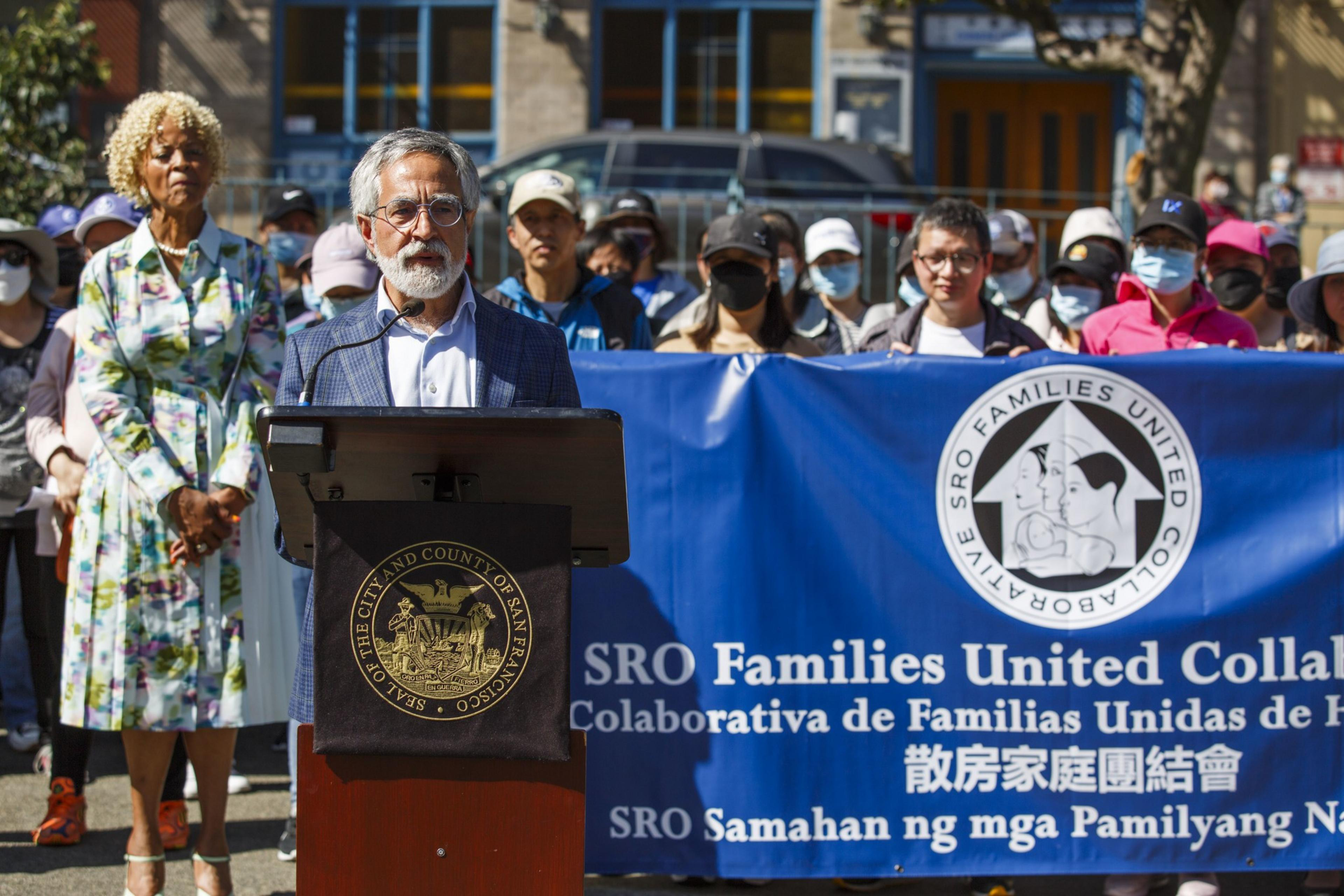

Last November, San Francisco voters shot down Proposition D, which would have sped up approvals for affordable housing projects and market-rate proposals that include affordable housing. And then this summer, supervisors offered a remix of the Stevenson Street decision by shooting down a 10-townhome project in Chinatown. One key reason: shadows.

If You Permit, Will They Come?

Aaron Peskin, president of the Board of Supervisors, has often been cast as the city’s preeminent NIMBY, a designation that makes him bristle. On Friday, he dismissed the war between YIMBYs and NIMBYs as “a self-serving narrative” and suggested the victory cries over SB 423 are overblown.

“Apparently nobody opposed them,” Peskin said. “They’re trying to create an opposition that you can’t find.”

Wiener and YIMBYs, a movement that started in 2014 when activist Sonja Trauss started suing cities that ignored state housing laws, would absolutely dispute that assessment. Peskin’s outspoken role on the Board of Supervisors in voting down Stevenson Street and the townhome project on Washington Street in Chinatown are just the latest examples she points to in the supervisor’s feisty two-decade political career.

“Aaron Peskin, as the president of the Board of Supervisors and as a supervisor for years and years, he extorted developers or he blocked housing,” David said. “Now [with SB 423], that dynamic is gone.”

Peskin called David’s assessment “crazy” and noted that housing issues in San Francisco are complicated, especially when considering issues of environmental justice and equity.

“We don’t want to make the mistakes that redevelopment made decades ago that ripped apart neighborhoods full of lower-income individuals and communities of color,” Peskin said, noting he is working on two housing bonds for 2024. “I’m not accusing [YIMBYs] of not caring about vulnerable communities, but you also have an obligation to look at these things.”

SB 423 is expected to kick-start the city’s permit approval process next year once state officials acknowledge the city is not meeting its housing permit goals and discretionary reviews are scrapped. But receiving a permit to build and having the pieces in place to break ground are two entirely different things.

“You can never think of it as one bill is going to fix all your problems,” Foote said. “This bill is going to fix many problems, and it will uncover other problems.”

Even the most ardent supporters of Wiener’s bills acknowledge that high interest rates will present significant barriers to developers. Planning officials also noted that SB 423’s requirement to hire skilled and trained union workers for the construction could also be a financial impediment.

Oz Erickson, chairman of Emerald Fund, a San Francisco development firm that has built more than 3,000 housing units in addition to commercial projects, agreed that interest rates will be something to monitor. But he seemed unconcerned about construction costs tied to union laborers.

“I’m not aware of any major project in San Francisco that hasn’t been done without skilled-and-trained,” Erickson said. “All of our projects rely on skilled-and-trained. It’s very important—in other areas [of California] it may not be, but it is in San Francisco.”

Perhaps the biggest issue still to be resolved in San Francisco is zoning, especially on the west side of the city where single-family homes dominate much of the Sunset. However, thanks to SB 330, a 2019 bill authored by East Bay state Sen. Nancy Skinner, it is illegal in California to modify zoning requirements to make it harder to build.

“Three giant things that need to be done to address affordability and displacement via our housing shortage are zoning reform, funding and streamlining the approval process,” David said. “SB 423 took care of streamlining the approval process.”

Annie Fryman, a former Wiener staffer who helped write SB 35 and now works on housing for the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association, better known as SPUR, credited SB 423’s passage to a sustained effort by YIMBYs.

“I’m glad YIMBYs were patient and stayed focused on the goal: Make dense housing easier and faster to build in places that need it,” Fryman said. “Activism is successful when you achieve enough system changes to make yourself irrelevant. And for so long, our activism has been focused on pushing the system we have. I think, finally, all that pressure has cracked something open.”