While sunbathing with her toes out on an unseasonably warm Dolores Park afternoon, self-professed Birkenstock lover Morgan Keys said there were few things that embodied San Francisco style more than the pair of German shoes.

“The most San Francisco thing I see is when someone’s wearing a puffy jacket and Birkenstocks with socks,” Keys said. “That’s just so SF to me.”

The brand—which has its U.S. headquarters in Novato, 30 miles north of San Francisco—has become shorthand for timeless California cool, the socks-with-sandals debate notwithstanding.

Founded as a family business in 1774 by German cobbler Johann Adam Birkenstock, the company went public on the New York Stock Exchange this month. Early valuations of the business placed the company at more than $9 billion, and it currently has a roughly $7.2 billion market capitalization after its first weeks of trading.

It’s one of the highest valuations ever for a shoe company, according to Beth Goldstein, a footwear analyst with the Circana Analyst Group. And as a public company, Birkenstock will have to answer to shareholders, who will certainly want to sell more shoes. That may run up against one of the company’s greatest strengths: its deliberate expansion.

“They have been very thoughtful with their distribution and very careful and very protective of the brand,” Goldstein said.

Birkenstock has seen a compound annual growth rate of 20% (opens in new tab) since 2014, in large part by maintaining a loyal customer base while expanding its appeal to younger generations by mingling “granola” vibes with high fashion.

But can a brand built on authenticity survive as a public company without compromising its principles and appeal? Other titans of casual fashion that have deep California roots—Levi’s and the Gap—offer model and cautionary tales, respectively.

“It’s almost this battle, this tension, between success and trying to maintain what made the brand so popular in the first place,” said Melissa Leventon, a fashion history professor at the California College of the Arts.

Ugly Cute

Sixty years before the rise of influencers, limited drops and signature collabs came Margot Fraser. The German American dressmaker brought the brand’s Madrid sandal to the United States in 1966, where it found a foothold in the Marin County health food scene.

Locals may know the iconic Birkenstock building off Highway 101 with its eye-catching white peaked roof. But that site has been empty since 2020, when the company moved into bigger digs a mile away shortly before the business sold to a private equity firm backed by luxury retailer LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton.

The brand’s dedicated store in Larkspur in Marin County—one of only four such brick-and-mortar outlets in the country—is just two miles from where the brand made its first appearance in the United States. In the nearly six decades since, the shoes continue to come back in fashion for young and old, crunchy and fashionista.

“They transcend time in terms of style,” said Birkenstock wearer Keys.

Footwear typically falls into one of two categories in the market—function or fashion—but Birkenstock has straddled the two, according to GlobalData retail analyst Neil Saunders.

“It occupies a very, very odd position,” Saunders said.

This idiosyncrasy has proven to be an advantage. Even as sales in the overall footwear market have flattened over the past year, Birkenstock remains an exception.

The company has vastly expanded its footwear collection over the years from a single “fitness” sandal—the Madrid—to include more than 800 models today, selling not only the traditional sandals but boots, sneakers and even a professional line for health care and hospitality workers.

Yet even with the proliferation of options, the company hasn’t flooded the market with shoes. Boston clogs and Barbie-inspired designs are consistently sold out, and Birkenstock footwear is hardly ever put on sale, according to retail analysts.

“They’ve resisted the urge to go gangbusters and put product out there, which can lead to over-inventory and discounting,” Goldstein said.

Product protection—epitomized by denim king Levi’s, which aggressively roots out imitators—has helped Birkenstock keep its cachet. Contrast this with the Gap, whose casual basics proliferated in discount bins with the expansion of malls in the 1990s.

Celebrity appeal has helped. Fashion icons—ranging from Kate Moss to Barbie star Margot Robbie—have worn them. A pair of Steve Jobs’ worn-out sandals recently fetched (opens in new tab) over $200,000 at auction, 100 times their 2016 sales price.

“It’s amazing how the wearer can change the context for the way something is worn,” said fashion historian Leventon. “It’s been transformed into something cool because cool people have done it.”

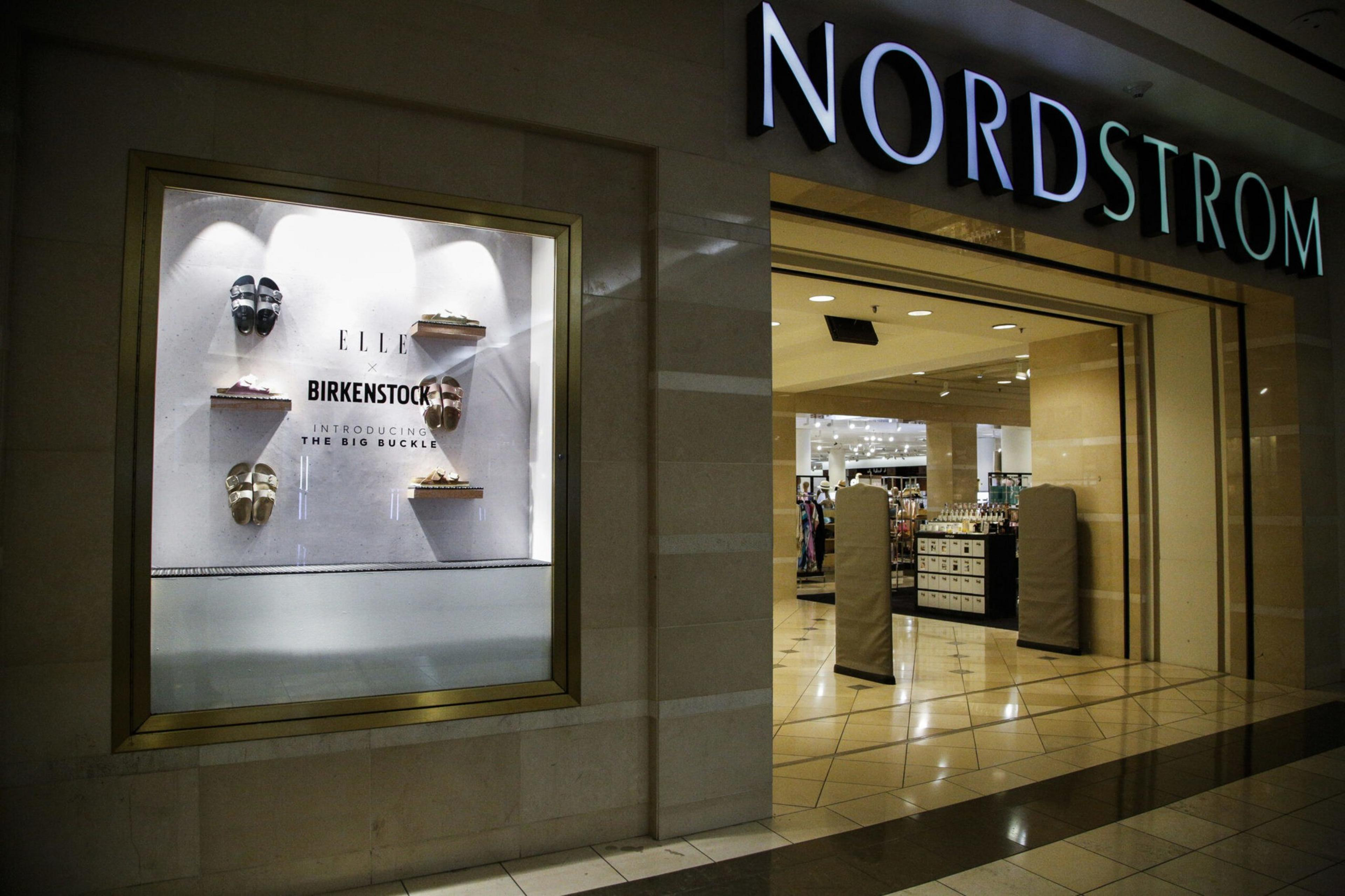

The company has leaned into the celeb street cred, inking collabs (opens in new tab) with high-end fashion designers like Valentino, Manolo Blahnik and Dior. Even Sarah Jessica Parker—whose Sex and the City character was the most discerning of shoe snobs—has been spotted (opens in new tab) wearing Birkenstocks.

Birkenstock’s partnership with streetwear brand Stüssy was what prompted San Franciscan Christian Ornelas to take the plunge on a black pair of Boston clogs.

“They had a specific colorway I wanted,” Ornelas said, noting many of his friends wear Birkenstocks.

While Levi’s has wielded such high-profile collaborations successfully—from Justin Timberlake to Emma Chamberlain—Gap’s failed collaboration with Yeezy (Kanye West) demonstrates the perils (opens in new tab) of choosing the wrong partner.

Birkenstock’s couture collabs are surprising since the company built its reputation on the opposite of fashion: In the Barbie movie, the Arizona sandal represents the real world. “Ugly cute” is how TikTokkers—who lifted the Boston clog to new heights of popularity with their influence—describe the shoes.

Retail analysts said younger shoppers appreciate gender-neutral designs that are practical and grounded.

“They’re like little potatoes,” said TikTokker Emilie Kiser, whose video about Birkenstock’s Boston clogs garnered nearly 8,000 likes. The virality of TikTok posts (opens in new tab) about the style led to a surge in sales, and the most popular color—taupe—remains sold out (opens in new tab) in stores and online.

The Souls of Birkenstocks

Do shoes have souls?

Birkenstock believes so—located in the sole of its trademark sandals. The company made only footbeds for over 200 years and did not sell a pair of shoes until 1963, when it put a single-strap “fitness” sandal on the market called the Madrid.

“It all started with the development of the sole,” Leventon said. “That was the heart of Birkenstock.”

The secret of the sole is the material—cork—which is breathable, naturally antibacterial and environmentally friendly. After wine bottle corks are punched out from the cork oak’s bark, the remnants are broken down into granules Birkenstock uses for its custom insoles.

The trees regenerate their outer layer every nine years, a process that inspired Birkenstock to develop a skin care line (opens in new tab) with cork oak extract because of what it claims are the material’s natural anti-aging properties.

The cork takes on the footprint of the wearer, making Birkenstocks unique to the individual. Birkenstock enthusiast Keys recalled a wedding party where everyone slid off their shoes—the majority of them Arizona sandals—to walk on the beach.

“At the end of the night, I put on what I thought were my shoes,” said Keys. “They were the same size and color, but I could just tell they weren’t mine.”

Jessica Floyd and her partner, Danny Conrad, used to make fun of Birkenstocks as unfashionable but have since converted—they’re now so devoted they visited the brand’s outlet store in Germany.

“Now, everyone wears them,” Floyd said.

Conrad loves that the shoes last forever and have traveled with him everywhere.

The shoe’s durability is something retailers over the years have complained about, telling Birkenstock USA founder Margot Fraser they could sell a lot more pairs if they wore out faster.

“Luckily, neither I nor Mr. Birkenstock gave in to that temptation,” Fraser wrote in her business memoir.

California Dreamin’

Fraser made it her mission to distribute Birkenstock sandals in America after discovering them on a trip to Germany in 1966. Shoe stores—and even podiatrists’ offices—turned Fraser down, leading her to sell them in a health food store in San Rafael.

As ground zero for the hippie movement, Northern California was the perfect place for Fraser to introduce the shoes to an American audience.

“It’s the perfect location because it’s where it all started,” Larkspur store manager Carlos Haro said. “It caters to the original fans.”

Haro said customers come in to shop with battered pairs of 30- and 40-year-old Birkenstocks. Shopper Antuanette Holder said she’s been wearing the brand for 35 years—her entire adult life—and now her kids wear them, too.

Yet, can a brand relying on grassroots appeal transition to a corporate juggernaut?

A less-than-spectacular market debut may have some people doubtful. As a multibillion-dollar company, it risks positioning itself as something it’s not.

“They priced this thing at four to five times sales for a business that has zero technology,” said Thomas Hayes, chairman at Great Hill Capital LLC.

It’s an open question if Birkenstock can stay in fashion without selling out.

A new rash (opens in new tab) of viral TikToks are unloading with hot—and negative—takes on the Boston clog, demonstrating the fickleness of influencers.

Only time will tell the destiny of the famed footwear, but Fraser’s words as she looks back on her improbable business rise seem prophetic.

“My experiences in the war taught me that you can never really own anything,” she wrote. “Everything in life is only on loan. With that lesson, I survived the joys and sorrows of my Birkenstock adventure.”