Twenty-six candidates running for office in San Francisco in March won’t be able to use their preferred Chinese names on the city’s bilingual ballots, officials have decided.

The Department of Elections told The Standard that 26 candidates, most of whom are not ethnically Chinese, failed to provide adequate documentation to prove that they were either born with the name or have been using the name for at least two years—as required by state law.

The 2019 law, which San Francisco recently decided to follow, was intended to prevent candidates from choosing deceptive or grandiose names that might confuse voters or give the candidates an unfair advantage.

Candidates who had their proposed Chinese names rejected “will be given a transliteration based on their English name,” the department said.

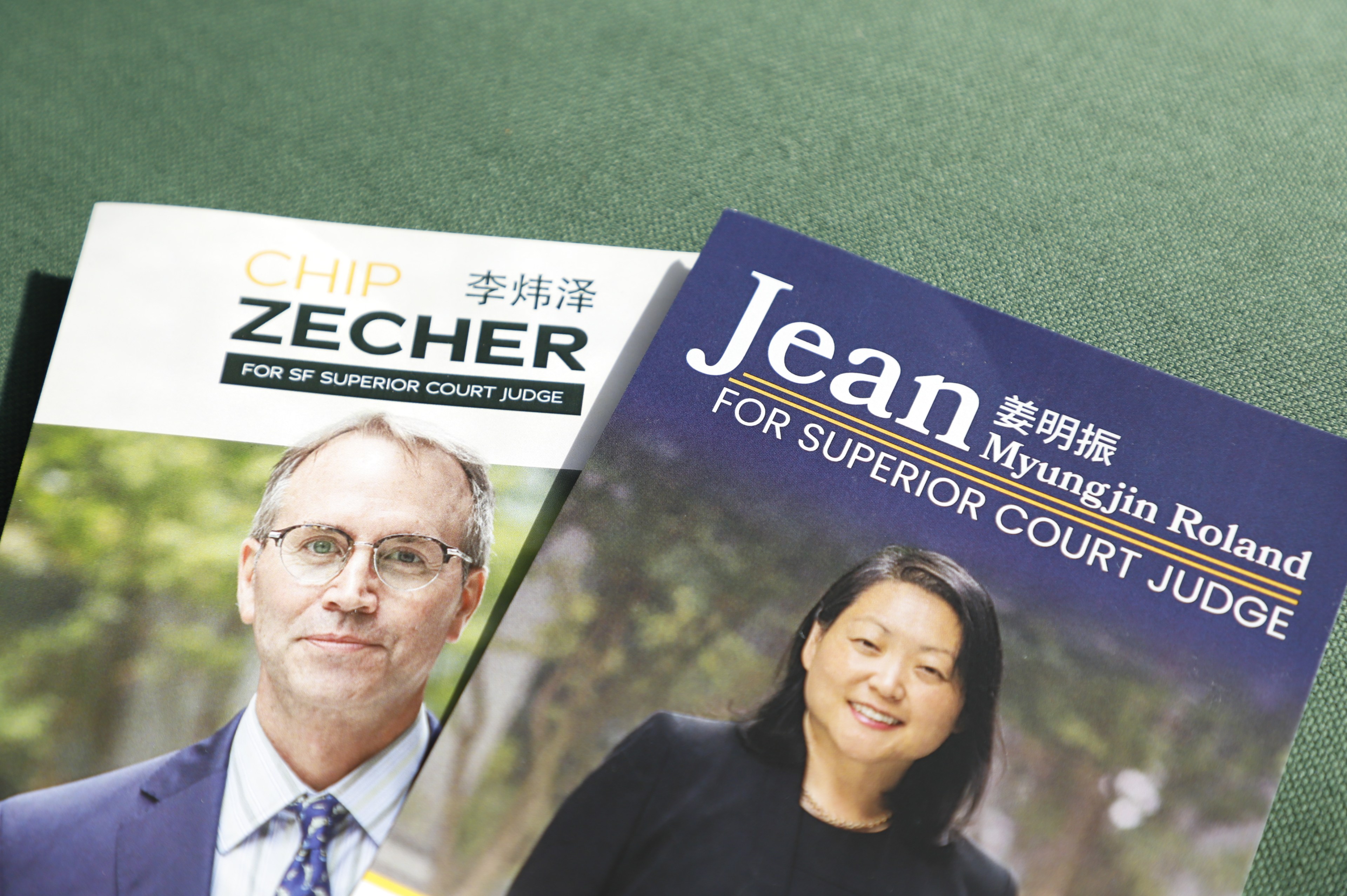

Among them are sitting Superior Court Judge Michael Begert and his opponent, Albert “Chip” Zecher, state Senate candidate Yvette Corkrean, and more than a dozen candidates running for the Democratic and Republican county committees.

The rejections are the latest development in an ongoing political controversy after the city’s election officials fully adopted the state law.

Why Do Chinese Names Matter?

Because of San Francisco’s large Chinese-speaking population, local ballots are bilingual in Chinese and English. Political candidates have developed a tradition of seeking “authentic” Chinese names, usually a two- or three-character name, rather than a long, wordy transliteration-based name with a separation dot assigned by the elections department. Such names can sound awkward to native Chinese speakers.

For campaign and name recognition reasons, candidates who have an official Chinese name will be mentioned accordingly in Chinese-language media. Without one, Chinese-language media often use different transliteration-based names, which can lead to confusion.

For example, San Francisco Police Chief Bill Scott, who’s not running for office and does not have an official Chinese name, is called by different Chinese names in three local Chinese newspapers—Sing Tao uses 施革, World Journal uses 史考特, and China Press uses 斯科特. The names are phonetically close to “Scott” in English but with different Chinese characters.

However, for political candidates, inconsistent Chinese names can harm their name recognition.

Mayoral candidate Daniel Lurie, making his first foray into politics, recently named himself 羅瑞德, and the name is printed on campaign materials and widely publicized in the Chinese media. But if he can’t prove that he was born with the name or has been using it for two years, he will likely be assigned a five-character transliterated name, 丹尼爾·露里.

Lurie’s chosen Chinese name means “auspicious” (瑞) and “virtue” (德), while the transliterated version name doesn’t have any meaning. It’s just an approximate pronunciation of his name in English: “DAN-knee-er LOO-lee.”

Lurie told The Standard that he’s aware of the issue and his team is looking into it as they may need to change their campaign strategy in the Chinese community.

“It’s my sincere hope that the Department of Elections sets a policy that serves the interest of the Chinese community, even if that presents a challenge for my campaign,” Lurie said in a statement. “It just means I have to work harder to make sure the Chinese community knows what I stand for, irrespective of the name provided to me by the city.”

Lurie’s declared opponents, Mayor London Breed and Supervisor Ahsha Safai, as well as potential entrants Supervisor Aaron Peskin and former Mayor Mark Farrell—all have chosen Chinese names as they have well-established political careers and can easily prove they have used their Chinese names for two years.

Hurting American-Born Chinese

Authored by state Assemblyman Evan Low, the law, AB 57, mandates that candidates use transliteration-based names unless they can prove that they were born with a character-based name or have been using such an “authentic” style Chinese name for at least two years.

San Francisco previously had rules that slightly differ from Low’s legislation, but city officials have since determined that the state law overrides local law.

American-born Chinese candidates have been among those most affected by the change. Initially, San Francisco’s Department of Elections released a list of 34 candidates with their Chinese names challenged, meaning they needed to provide additional evidence to fulfill the requirement. About half a dozen were people of Chinese descent.

Unlike those born in Chinese-speaking regions with Chinese-language birth certificates, American-born Chinese candidates were outraged as they were scrambling to find evidence of their Chinese identity.

After some candidates threatened a protest outside of the elections department, officials loosened up the rules a little bit, allowing family statements, under the penalty of perjury, to prove that the candidate was given that name early on, even if not on an official document.

Low’s office expressed concerns about the state law hurting American-born Chinese candidates and said it would look into the issue to “correct the injustice.”

Cultural Appropriation Controversy

Even though the state law was passed in 2019, San Francisco wasn’t following it until Supervisor Connie Chan sent an official inquiry to the elections department in October, urging the agency to explain why the city hadn’t implemented the law.

The inquiry, an action supported unanimously by the Board of Supervisors, prompted the elections department to get into compliance with state law.

However, Chan, an outspoken progressive leader and the only Chinese American supervisor on the board, faced a backlash after the move began affecting American-born Chinese.

In an interview Thursday, Chan said the recent drama has provided an opportunity for the Chinese community to think deeply about what Chinese ethnicity means and for non-Chinese to think about whether their chosen Chinese names amount to “cultural appropriation.”

“For those who are using Chinese names, they will have to justify and explain why they have this privilege of using Chinese names,” Chan said.

Ironically, Chan gave Supervisor Matt Dorsey, a white man, his Chinese name. She explained that Dorsey, a longtime local public relations expert and city hall staffer, has a long track record of working with the Chinese community, so he asked for a Chinese name long before he ran for office. Many non-Chinese city employees who work closely with the Chinese community also have Chinese names.

Chan also criticized some American-born Chinese for not being proud of their Chinese heritage until they jumped into politics and struggled to establish their Chinese identity.

“If our name and our ethnicity is so important, we need to find ways to honor it, and there will be evidence [to prove it],” she said.