Tucked away in a private event space on the second floor of the swank Epic Steak restaurant on the Embarcadero, a who’s-who of elected officials and union heads in San Francisco gathered last week for a party thrown by a government lobbying firm.

State Attorney General Rob Bonta, a likely candidate for California governor in 2026, mingled with guests who included top union reps for city firefighters, janitors and carpenters, along with District Attorney Brooke Jenkins and San Francisco Supervisors Shamann Walton and Ahsha Safaí. Former Mayor Willie Brown delivered remarks in his official role as San Francisco’s roastmaster general, and Daniel Lurie, a wealthy nonprofit founder who is running for mayor, also showed up to glad-hand.

But one person was conspicuously absent: Mayor London Breed.

While she was invited, the mayor’s appearance could have made for some awkward conversations—contracts for nearly three dozen public employee unions, not including police and firefighters, will expire this summer. Multiple labor leaders at the party said a nasty fight is brewing in San Francisco. The city is staring down a projected $800 million deficit over the next two years, meaning vacant jobs will be eliminated, contracts could be cut and services will likely diminish. Adding to the degree of difficulty in negotiations, a court ruling in 2023 has potentially opened the door for city workers to strike for the first time in more than four decades.

The fallout could have devastating consequences for Breed, who is seeking a second full term. Polling shows her positions align with the priorities of most residents, but her approval ratings have been dismal and the field of challengers could soon grow.

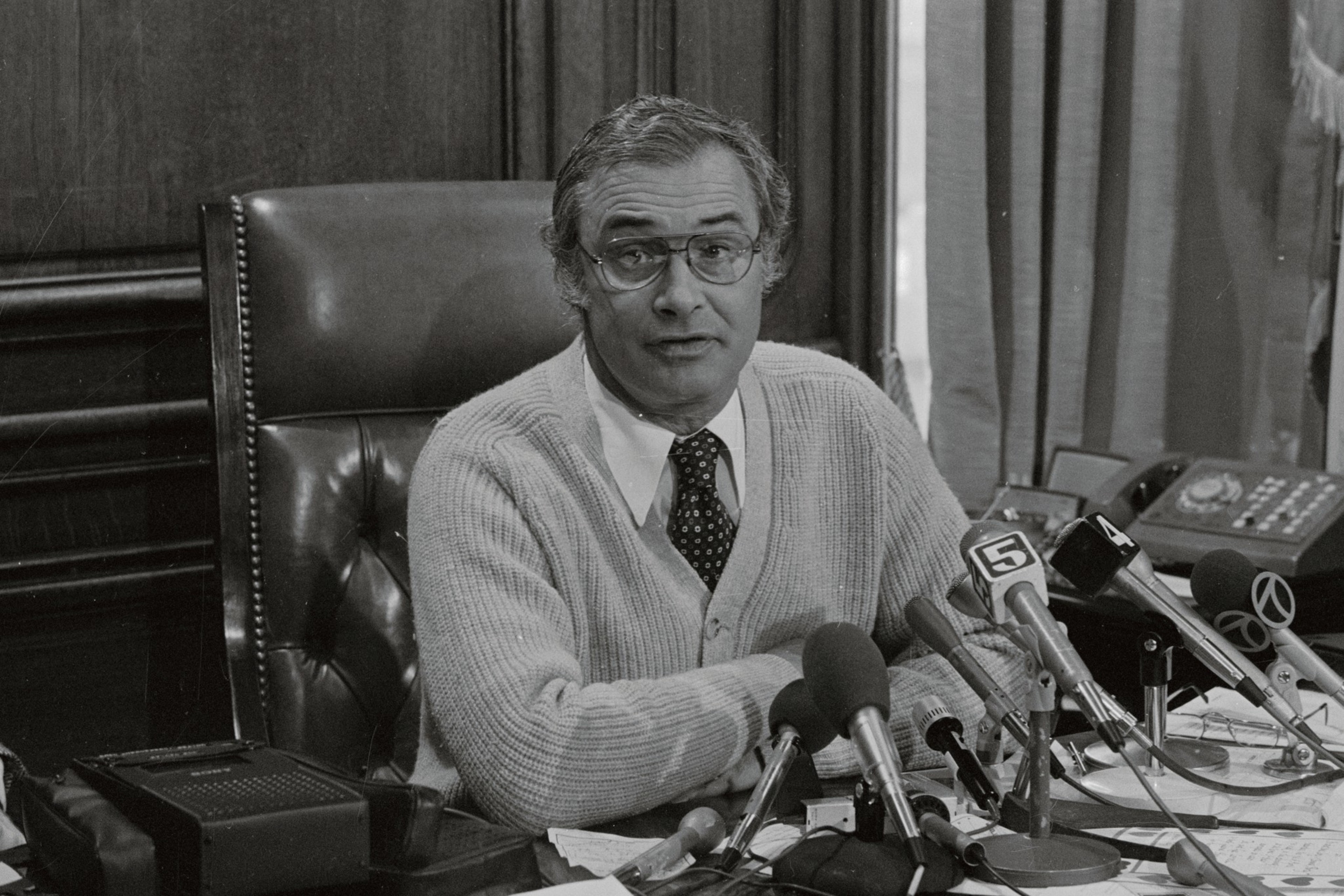

The last public employee strike in San Francisco was in 1976 (opens in new tab). It lasted 39 days, with nearly 1,800 workers walking off the job to picket the zoo and airport. Buses and streetcars halted, and 250,000 daily riders were left stranded. A similar scenario would potentially infuriate lukewarm Breed supporters as well as residents who normally sit on the political sidelines.

“I think any year that labor is negotiating their contracts, the mayor is in a tough place, whether it’s an election year or not,” said Maggie Muir, Breed’s political consultant. “Yeah, it’s a tough year, we’re facing deficits and she has to make tough decisions.”

Breed was supposed to face reelection in November 2023, but she has found herself in this sticky wicket thanks to Supervisor Dean Preston, a political nemesis of the mayor’s. In 2022, Preston put forward Proposition H, a ballot measure to move the mayor’s race to even years to coincide with presidential elections.

Preston suggested the shift in elections, which gave Breed an extra year in office, would encourage greater voter turnout, as the city sees about 80% of registered voters show up in national election years. In 2019, when Breed was elected mayor after winning a special election a year prior, turnout was less than 42%.

Staff in the Mayor’s Office said they never would have agreed to a two-year labor contract for 30,000-plus city workers in the summer of 2022—ending in a 10% wage increase spread over three years—if they had known the mayor would be renegotiating just months ahead of a 2024 reelection fight.

Preston, who stands on the progressive side of the aisle compared with Breed’s more moderate Democrat positions, swatted away any suggestion that Prop. H was motivated with labor negotiations in mind. He instead took aim at one of the mayor’s 2024 ballot measures, Prop. C, which would waive taxes to convert commercial buildings to residential use.

“While the mayor is bending over backwards to punish the poor and give tax breaks to billionaires, like with her absurd Prop. C tax giveaway on the March ballot, I’ll continue to stand with working people,” Preston said in a text message. “Whether or not it’s convenient for her to negotiate labor contracts during an election year is not my concern.”

Multiple political observers told The Standard that Breed will need to walk a fine line in how her office handles the public messaging on labor negotiations, as unions have strong support (opens in new tab) here and nationally, while the mayor’s approval ratings have plummeted coming out of the pandemic.

“Let’s just be clear: I have numbers on labor, and this is a labor town,” said Jim Ross, a local political consultant who has worked on races at every level of government. “People in San Francisco support labor, period.”

Breed won a special election in the summer of 2018—six months after the death of Mayor Ed Lee—with the help of a diverse coalition of voters. But a broad consensus of support from labor is not seen as likely in this coming year’s election, which could open a door for a more progressive challenger. In 2018, Breed benefited from strong support from the firefighters union, but more than half of the nearly $900,000 in spending was funneled to the union’s political committee by tech and real estate interests, according to campaign records.

Ross suggested Breed could “shoot the moon” in a high-risk strategy that blames the current deficit on wage increases for unions, attempting to sway public opinion to her side in the event of a work stoppage.

“The problem is she doesn’t have a lot of political capital, or a lot of goodwill, built up with voters in San Francisco that would be useful in the case of a big fight with labor,” Ross said.

David Latterman, a longtime political analyst in San Francisco, countered that unions will also need to be smart in not overplaying their hand. International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers Local 21, which represents city engineers and many mid-level managers, sent letters to its members telling them to save money in the event of a strike this summer, and Service Employees International Union Local 1021, San Francisco’s largest union with roughly 16,000 city workers, has been similarly alerting its members of a potential work stoppage.

“People vote on the services that immediately affect them day to day,” Latterman said. “Everyone says they’re pro-labor until their pothole doesn’t get fixed. The question is, ‘How aggressive is the mayor going to be making this case?’ I don’t think the mayor has the deftness or her team has the guts to go that direction.”

The City Attorney’s Office appealed a ruling last summer by the state’s Public Employees Relations Board (opens in new tab), which found that San Francisco’s ban on public employee strikes—passed through ballot measures as a result of the work stoppages in the 1970s—was unconstitutional. This has left the question of whether city workers can legally go on strike in limbo.

“The City Attorney’s Office supports labor rights, but we have a duty to defend City laws, especially those passed by the voters,” said Jen Kwart, a spokesperson for the City Attorney’s Office. “We defend the voters’ policy choices unless there are no plausible legal arguments to defend them, and in this case, we must defend the will of the voters.”

This isn’t the only monumental difference in how unions and city officials see the battle lines.

Bianca Polovina, the president of IFPTE Local 21, said that the city should be taking a harder look at how it outsources work to nonprofits and private companies, rather than eliminating vacant positions. The city currently has more than 3,700 job openings, and one path Breed is taking to tighten the fiscal belt is eliminating positions.

“We’re focused on addressing the understaffing crisis, which is debilitating our public services, and also reining in wasteful spending on private contractors,” Polovina said. “What is different and unique about 2024 is that we have more information than we’ve ever had about why the public services that we provide are integrally tied to the biggest issues facing San Francisco.”

Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who serves as president of the Board of Supervisors and is rumored to become a potential challenger to Breed, suggested that the mayor boxed herself into her current predicament by passing a record budget last summer when deficit projections were already bleak.

“They entered last year’s budget thinking that they didn’t need to make any consolidations, any adjustments, any cuts,” Peskin said. “It was a mistake then; it’s a mistake now. It just means that the magnitude of the hill they have to climb is exponentially larger.”

Safaí, a supervisor for the Excelsior who has cast himself as the labor candidate in the mayor’s race, said the current budget crunch was foreseeable, as federal relief money from the pandemic would no longer be available and vacancies in Downtown commercial towers led to dwindling tax revenue.

“Instead of tackling the hard issues last year and leading, the mayor chose to put them off until this year when our financial outlook is worse,” Safaí said. “The mayor should be engaging with labor herself, directly and leading the discussions to come to a resolution instead of complaining about the hand she has been dealt.”

The Mayor’s Office began labor negotiations on Dec. 27, and those talks are expected to heat up starting next week. Labor unions are holding a rally in front of City Hall on Wednesday to lay out their demands and drum up support for city workers.

While residents may be sympathetic to their concerns, many in San Francisco also believe the city is headed down the wrong track, and there needs to be a greater, if not more efficient, investment of city funds to improve services. As many people contacted for this story noted, a union endorsement will not weigh as heavily as how residents feel about the state of the city.

“I think it’s still a union town, but at the same time, voters aren’t looking to see which unions are supporting which candidates,” Muir said. “I think they’re looking at the candidates’ policies that they support. Right now, that’s really focused on public safety and addressing the drug crisis on the streets.”

All of that is true, but a work stoppage would not only stall progress but also roll back any gains made over the last year. The only thing holding the line, in that case, would be picketing workers.