Jermaine Joseph, a city employee for the Port of San Francisco, was doing his maintenance rounds at Crane Cove Park on a sunny morning in May 2022 when he spotted something unusual: nearly 50 abandoned pieces of art arranged on a cement bench.

“It was really strategically set out in a nice pattern,” he said. “And looking at the frames and the paper, you could tell someone put a lot of time into them.”

Joseph knew the artworks had not been there for long—no morning dew had collected on them. But there was no evidence of an owner anywhere on-site.

A port employee for 17 years and a general laborer supervisor, Joseph was used to encountering all kinds of refuse left near the shoreline. He wondered if he should load the art onto the dumpster, but something stopped him: This felt different. He alerted his colleagues, Arianna Cunha and Tim Felton, who happened to be along with him that day to inspect a sprinkler system.

“This wasn’t something that was in a cardboard box,” said Cunha, an administrative analyst for special projects for the port. Many of the pieces were framed, and those that weren’t had small stones placed upon them so they wouldn’t blow away in the bay breeze.

Cunha had been walking around the pieces with Felton for about five minutes when they noticed the next clue—the majority of the artworks had the same signature on them, and some had dates, ranging from 1920 to 1941. They decided to pack up the pieces and take them back to their offices at Pier 50 for a deeper look.

“We sat there for a good amount of time, but there was nobody,” Cunha said. “We all looked at each other—this is so random, right?”

The global search begins

Cunha and her colleagues laid out the artworks in the conference room to inspect the pieces more closely. Thirty-eight of the 48 pieces—which included drawings, prints and paintings crafted with an obviously skilled hand—had variations of the name Ary Arcadie Lochakov.

“That’s when we got invested in this story,” Cunha said.

A piece signed 1935 by Russian Jewish artist Ary Arcadie Lochakov is pictured at the Port of San Francisco Maintenance Shed D in San Francisco. | Source: Jason Henry for The Standard

Cunha called the San Francisco Police Department and confirmed there had been no recent reports of stolen or missing art. There was also no surveillance video of the area to give a clue of who might have abandoned it there.

From the scant details she could find online (opens in new tab), Cunha learned that Lochakov was a Jewish artist who was active in the interwar period in Paris. She began contacting Jewish museums and cultural institutes that might be able to fill in the picture of who the artist was and how so much of his work had miraculously appeared on a park bench in San Francisco.

Cunha pieced together scraps of information from organizations like Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem and the Museum of Jewish History and Art in Paris. She authenticated the artworks as Lochakov’s by comparing them to prints of the artist held by the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum in Northern Israel. She learned about his one known painting from art specialists Nadine Nieszawer and Pascale Samuel.

And bit by bit, a picture of one man’s eventful, and ultimately tragic, life emerged.

Officer, artist, martyr

Ary Arcadie Lochakov was born to a progressive, artistic Jewish family in 1892 in Bessarabia in the former Russian Empire, where his father ran a photography studio. He served in World War I as an officer in the Russian Army and moved to Paris to pursue an art career.

His works were entered into prestigious shows like the Salon d’Automne—a renowned Parisian art fair (opens in new tab) that established the reputations of world-class artists like Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse. Under the Nazi occupation of Paris during World War II, Lochakov was forced into hiding in a Jewish ghetto. He died from malnutrition on Oct. 5, 1941.

Once she had cobbled together the broad strokes of the artist’s life, Cunha knew the port workers had lucked upon something historically—and perhaps financially—significant.

“I realized this can’t just stay in our conference room anymore,” she said. “We need to make sure this goes somewhere.”

She approached the port’s executive director, Elaine Forbes, with her findings. Her boss agreed: The artworks needed to be in a safe place where they could be researched and viewed by the public, not in the port’s storage shed. Cunha reached out again to the Israeli and French art experts—but this time in search of a forever home for the pieces.

Yet she still didn’t have an answer to her biggest question—how did nearly 40 works of art by a long-dead artist with no known immediate family end up halfway across the world?

The traces of Lochakov—and the trail—might have disappeared entirely had it not been for one man: Hersh Fenster.

‘The big question mark’

A Yiddish author and journalist from Galicia who settled in Paris, Hersh Fenster made a promise to a young group of artists in Paris during World War II. If he were to survive the war, he’d do everything he could to tell the story of the Jewish members of the School of Paris, a revolving group of artists who gathered in Europe’s art capital in the first half of the twentieth century. In addition to revered artists like Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Marc Chagall, the group included many little-known artists who, like Lochakov, had fled persecution in their native countries to pursue careers in the human-rights haven of Paris.

Fenster kept his promise, and in 1951, he published a book in Yiddish titled Our Martyred Artists, telling the story of 84 School of Paris artists, most from Eastern Europe and Russia, who perished in the Holocaust. Unlike Chagall, who wrote the preface to Fenster’s book, Lochakov and the other perished Jewish artists did not have the time or luck to become famous.

Fenster died in 1964, and years later his daughter entrusted his archives and research to Nadine Nieszawer, an art dealer who herself studied the artists known as the “Lost Shtetl of Montparnasse.” The gift helped Nieszawer recognize her purpose in life—to carry on the legacy of Fenster and her own father, an art dealer who specialized in the lost Jewish artists from the Paris School. She has since written a book (opens in new tab) about the artists and continues to authenticate, evaluate and collect their artworks.

“It’s a treasure,” Nieszawer said of the discovery at Crane Cove Park. “There is only one other work previously known by Lochakov.”

That work, a painting her Parisian grandparents had purchased directly from the artist, is now owned by the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris. It is a depiction of Lochakov’s best friend David Knout, a key figure in the Jewish Resistance. Mysteriously, just before the San Francisco Port’s Cunha contacted Nieszawer about their finding, she had received a letter asking her to photograph a painting—the one by Lochakov.

“It was very odd,” she said.

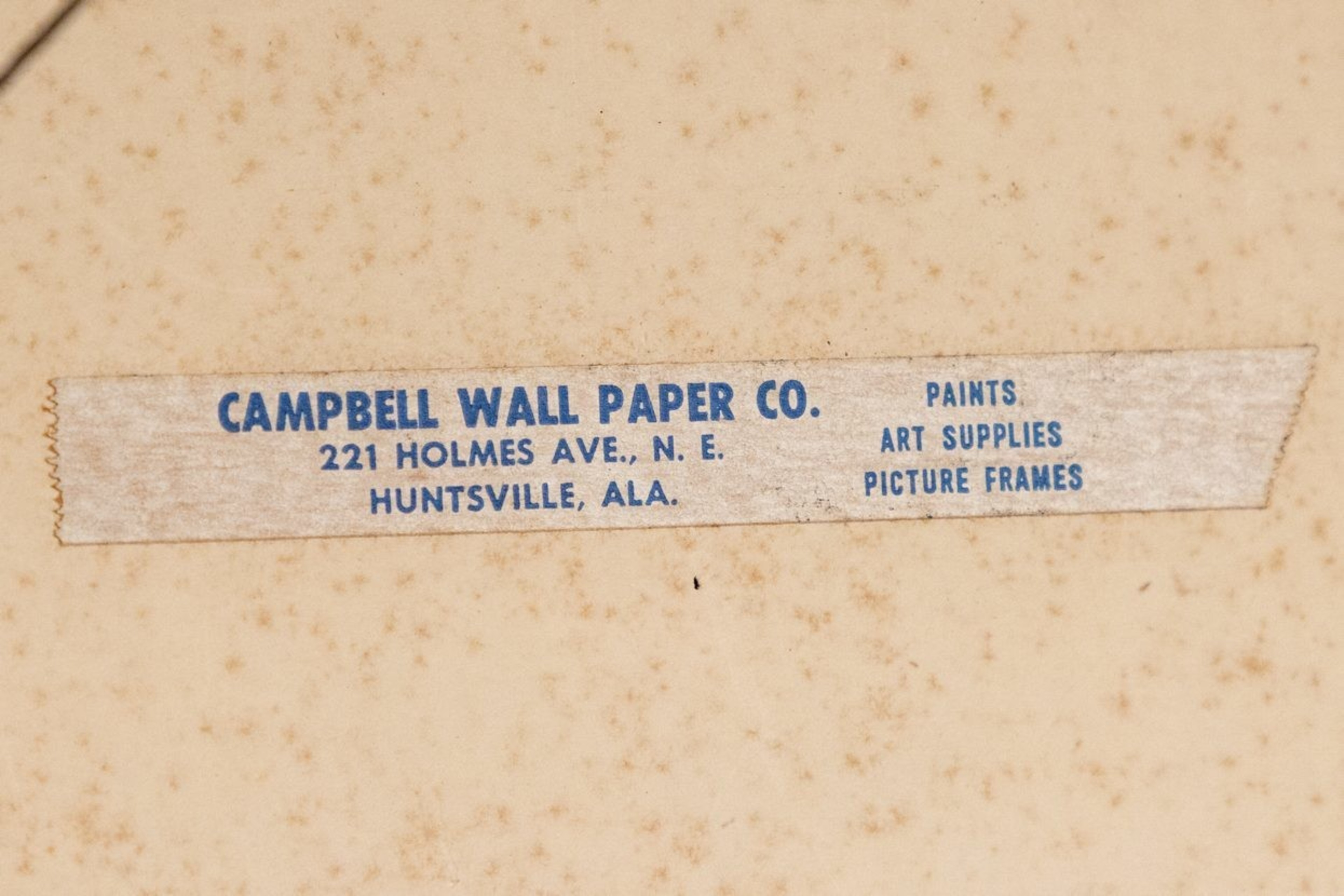

Odder still is the lack of any clear explanation of how the paintings arrived in such pristine condition in a San Francisco park more than 80 years after their creator’s death. The only clues of a chain of custody come from the frames, some of which hail from the Campbell Wall Paper Co. in Huntsville, Alabama.

Some of the works by the artist Ary Arcadie Lochakov were framed in Huntsville, Alabama, as evidenced on the back of an artwork. | Source: Jason Henry for The Standard

Perhaps a friend or confidant of Lochakov’s transported the works to California via the American South. Or perhaps there are more nefarious links. The Nazis made no secret of their love of art, or their penchant for ransacking the wealth of nations. Could an American descendent of the Nazi occupiers of Paris have ended up with a stockpile of Jewish art? Had that person dumped the paintings there in order to avoid any association with their provenance?

The questions have no end.

A legacy lost and found

For Pascale Samuel, a curator at the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris, the appearance of Lochakov’s works in San Francisco is one of the greatest art mysteries she’s encountered.

“He didn’t have a wife, any children, a family,” she said. “No one after his disappearance concerned themselves with his work.”

The discovery of Lochakov’s work, the experts say, is not significant because of its market value—Lochakov’s one previously known painting was bought at auction by the Museum of Jewish Art and History for $27,633. Earlier this week, another work by the artist surfaced (opens in new tab) at a French auction house, priced at 1,800 Euros.

But the real value of the discovery may not be monetary—it is the restoring of a long-lost memory, Samuel said. Unlike artists such as Soutine, who left a large artistic footprint behind (opens in new tab), Lochakov’s legacy had been almost completely erased. It’s re-emergence is, in some ways, incalculable.

“He should have lived another 20 years and made a lot more art,” Samuel said. “But Nazism and the Holocaust stopped that.”

Even with all her expertise on the Jewish martyred artists, Samuel can’t fathom how Lochakov’s works ended up there on that sunny May morning in Crane Cove Park.

“We don’t know what happened to Lochakov’s studio after his death,” she said. “Was it pillaged, stolen from? It’s a hypothesis.”

But what Samuel knows for certain is the incredible nature of the most unexpected art discovery of her decadeslong career.

“I was doing a conference on disappeared artists, and among the three I highlighted at the end was Lochakov,” she said. “And the next day, I get the message from Arianna at the end of the world, in San Francisco.”

Gallery of 11 photos

the slideshow

Both Nieszawer and Samuel spoke about the uncanny timing of Cunha’s messages to them, missives that made the whole situation feel fated. For Cunha, Felton and Joseph, the discovery of the artwork also became a stack of what-ifs, a nesting doll of near-misses with oblivion.

What if the city worker Joseph had tossed the pieces straight onto the dumpster truck? What if Cunha hadn’t put the time in to research the artist’s significance? What if Nieszawer hadn’t inherited her own Lochakov, or decided to continue Fenster’s work?

In the meantime, a resolution quietly passed in the city of San Francisco on Jan. 19, 2024, allowing for the transfer of Lochakov’s works to the Museum of Art and History of Judaism in Paris, the largest museum of its kind in France. Located in the historic Jewish neighborhood of Le Marais, the museum’s permanent collection includes works by Chagall, medieval gravestones and the only surviving Ashkenazi ark from the 15th century. It is a place where Lochakov can be studied and appreciated.

Port staff intends to display Lochakov’s artwork at the port—exactly when and where has not yet been decided—before it makes its voyage to France. In the meantime, Cunha continues to collect new information about the artist and his rediscovery. Perhaps you, dear reader, also have a clue to pass along.

“It’s not that we don’t know or are never going to know,” she said of the Lochakov art mystery, “but it’s divulging as we go.”

Lochakov’s body of work could have been lost. But the spirit of him is out there somewhere, making sure he’s not forgotten.

“Maybe it’s the ghost of the artist who sent us a sign,” Samuel said.