This week, with little forewarning, more than 70,000 State Farm policyholders in California were unceremoniously informed that their insurance policies would not be renewed.

Via a thin boilerplate letter, the state’s largest insurer gave little in the way of details to some 30,000 residential customers and 42,000 commercial apartment policyholders. But the announcement was met with shock and dismay by industry observers and customers.

“It’s confounding, it’s frustrating and it feels really outrageous, honestly,” said Amy Bach, the executive director of United Policyholders, a San Francisco-based nonprofit that advocates for insurance consumers. “We’re in a place where, unfortunately, consumers don’t have other options, and what it feels like is they are ratcheting up the pressure.”

The timing of the announcement—an escalation from the company’s decision last May to cease writing new policies for customers in California—is particularly striking. It comes the week after State Farm raised home insurance rates for its customers by 20% and after California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara introduced new policies (opens in new tab) around “catastrophic modeling” the industry has long clamored for.

These allow insurers to use forward-looking modeling around wildfire risk and climate change to price policies instead of solely using past trends. Although the move by Lara was hailed by the industry, companies stopped short of committing to returning to the state.

“This decision was not made lightly and only after careful analysis of State Farm General’s financial health, which continues to be impacted by inflation, catastrophe exposure, reinsurance costs, and the limitations of working within decades-old insurance regulations,” State Farm, wrote in its announcement, which noted the impacted customers represented just over 2% of their total policies.

State Farm isn’t alone in attempting to reduce its financial risk in California. A string of major companies, including Farmers Insurance, Allstate and Traveler’s, have cut their business in the state or dropped out entirely.

Rex Frazier, president of the Personal Insurance Federation of California, a trade association of the state’s major insurers, defended State Farm’s decision as a matter of fiscal responsibility.

“This is a big deal, as the market leader [State Farm] feels the responsibility to stay open when others can’t,” Frazier said, adding the decision’s timing was just coincidental. “They did until they couldn’t. They kept writing when others didn’t until clearly they ran out of runway.”

In a letter sent to the Department of Insurance (opens in new tab) explaining its nonrenewal decision, State Farm wrote that its surplus of capital to pay for claims has declined by 68%, from $4.1 billion in 2016 to $1.3 billion in 2023. Furthermore, because of its deteriorating solvency, the company wrote it is required to file an action plan to restore its financial condition by April 15.

California’s Department of Insurance did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the nonrenewal.

Harvey Rosenfield, founder of the nonprofit Consumer Watchdog and author of Prop. 103, which governs the state’s insurance market, said he views the nonrenewal as a negotiating tactic to win more concessions from state officials.

“Basically, the insurance companies are putting a gun to the head of the people of California … and the commissioner is giving into the ransom,” Rosenfield said.

‘A ticking time bomb’

Most insurance industry experts agree that rates have not been able to rise fully in response to the increasing risk of disaster due to climate change.

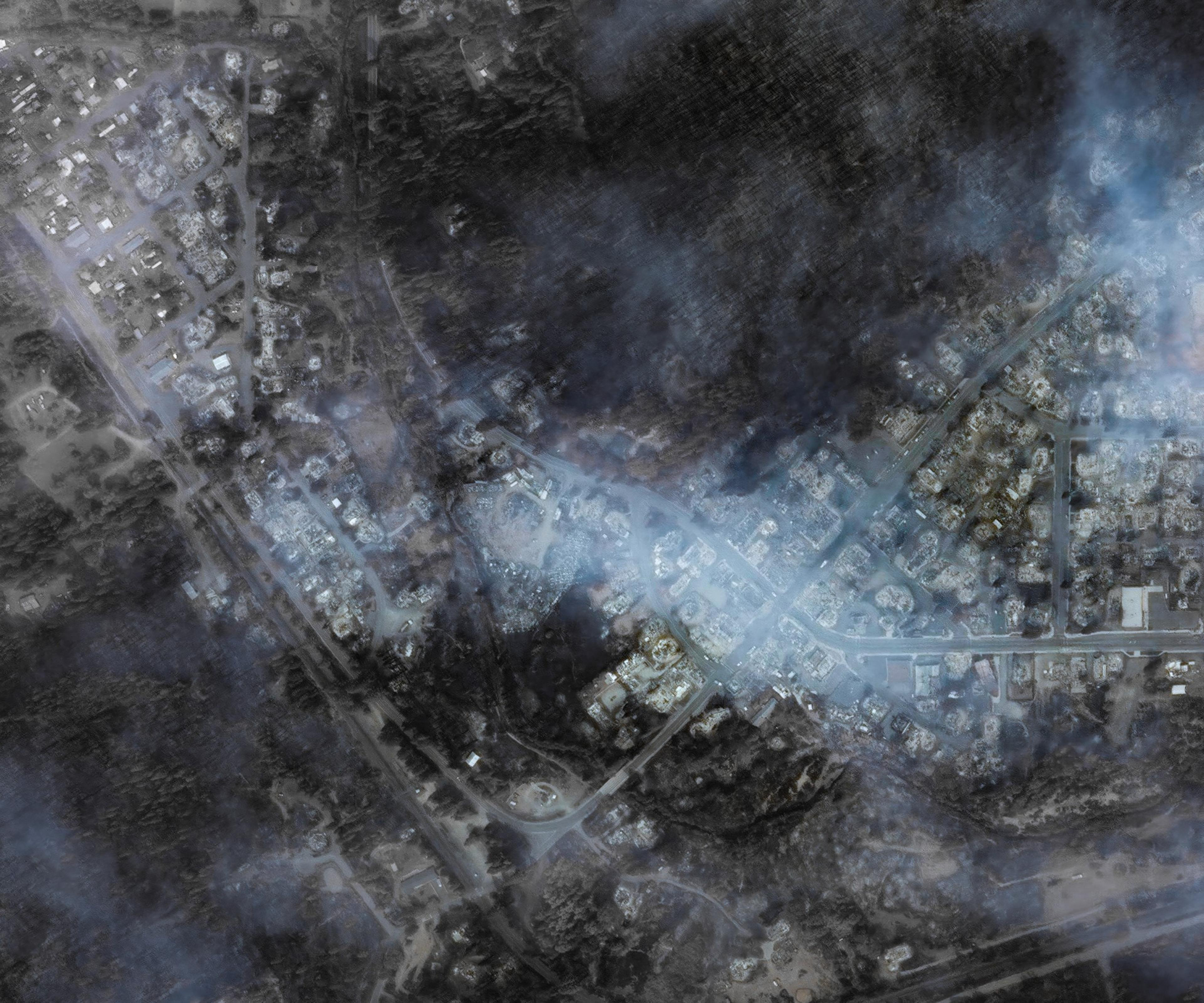

Buffeted by rising construction costs and wary of the risk of catastrophe in the form of another major wildfire season that could mean billions in claims, the state’s largest insurers have decided to pull back, drying up large portions of the insurance market.

This trend line will have the ultimate impact of pushing more people onto the California FAIR Plan, the so-called insurer of last resort. The FAIR Plan is a program funded by insurance companies meant to provide basic fire insurance for those who can’t access it in the private markets.

But that last resort has increasingly become the only option for homeowners amid broader chaos in the state’s insurance market—and that safety net is starting to tatter. In 2023, the number of FAIR Plan policies increased 22% to 350,000. Applications for coverage have gone from a few dozen daily to now more than 1,000. And FAIR Plan’s risk exposure has risen more than six-fold from $50 billion in 2018 to $311 billion in 2023.

“It’s a ticking time bomb,” Michael D’Arelli, executive director of the American Agents Alliance, an insurance agents’ association, said at a March 13 Assembly hearing (opens in new tab). “Things need to change because, statistically, we are going to have a major event and meltdown. The numbers don’t lie.”

Victoria Roach, the president of the FAIR Plan, said that a widespread fire or disaster event would require going back to the insurance companies for a major assessment charge to help cover the costs of claims.

“It’s a gamble. We are one event away from a large assessment,” Roach said. “There’s no other way to say it because we don’t have the money on hand and we have a lot of exposure out there.”

The reinsurance roadblock

A major sticking point with private insurers weighing whether to continue doing business in California is the issue of passing through reinsurance costs to policyholders.

Essentially, reinsurance refers to policies taken out by insurance companies themselves to guard against the potential for unexpectedly high claims and to balance out their risk.

The problem is that the cost of reinsurance has dramatically risen in recent years due to increasing global conflict and black swan events like the pandemic.

Currently, in California, reinsurance costs are prohibited from being included in company calculations around premiums. But other states like Florida and North Carolina allow insurers to pass through the costs.

Consumer advocates argue that changing this rule would mean massive premium increases, but Frazier, the insurance trade association head, said it is a necessary step to allow insurers to resume writing new policies and ease the stress on the FAIR plan.

“If we don’t have a mechanism for insurers to afford their reinsurance costs, they’re going to serve fewer customers,” Frazier said. “Nobody wants higher prices, but if the global reinsurance market goes crazy, what do we do? Ignore it?”

Lara, the state insurance commissioner, is expected to unveil new policies around the use of reinsurance in premium costs, but they have yet to be announced.

In the meantime, Los Angeles Congressman Adam Schiff, the frontrunner for the state’s open U.S. Senate seat, has introduced federal legislation establishing a federal reinsurance program that would require participating companies to offer policies that cover all natural disasters.

Karl Susman, president of the Susman Insurance Agency in Los Angeles and an insurance market expert, said that officials can balance consumer protection with the actions necessary to stabilize the market. But, he added, speed is of the essence.

“At the end of the day, all of this still could be fixed and can be fixed and will be fixed,” Susman said. “But if there’s a major event in the meantime, we are in deep doo-doo.”