Twenty-eight-year-old Alex Lee is well aware of how much of an outsider he is in Sacramento.

Four years ago, he was elected, in a shocking victory, to the state Assembly with a barren resume that included only one full-time job. At the time, the Bernie Sanders-endorsed socialist still lived at home with his mom and made a lot of noise being the first openly bisexual state legislator in state history. Fairly or not, it was easy to write him off as well-intentioned but intensely naive.

“People just assume that because I’m young that I know nothing,” he said in a recent interview at his district office in Milpitas, a suburb just north of San Jose.

On his Instagram page (opens in new tab), Lee proudly lists “Zoomer” as a descriptor alongside “progressive” and “NUMTOT,” an in-joke referring to a social media page (opens in new tab) for urban planning and transit nerds. He’s also one of only five renters in the entire state Legislature. Those labels might draw eye rolls from his colleagues and detractors, but Lee views his youthful exuberance as a weapon.

“There just aren’t many people out there with unorthodox ideas approaching them with sincerity,” Lee said.

One of those ideas is his newest signature bill, which he views as critical in addressing the state’s worsening housing crisis.

Known as AB 2881, the proposal represents arguably California’s most ambitious attempt to boost its housing supply in recent memory. If passed, the state would create a public agency to develop housing directly paid for by taxpayers.

Lee calls this evolution of public housing “social housing” since rents, or in some cases, proceeds from home sales, would be funneled back into the agency for further activity. Instead of exclusively focusing on low-income households, the objective would be to create vibrant mixed-income communities.

It’s a radical shift from what Californians are used to. And in perhaps the most surprising development in a short political career already full of them, Lee’s scheme is not getting laughed out the room, but gaining major traction with his fellow lawmakers.

Social housing’s evangelist

Lee was sworn into the state Assembly in December 2020 on the floor of Sacramento’s Golden One Center, masked, with no guests and socially distanced from his colleagues. The dust from a polarizing presidential election had yet to settle and California was still in the throes of a strict lockdown.

But Lee was inspired when he saw the ability of state and federal officials to implement decisive programs in response to the pandemic, such as an increased child tax credit, mass eviction protections, stimulus checks and widespread Covid testing sites.

When faced with crises like the growing issue of housing unaffordability and homelessness, Lee argues there is often more alignment politically for government intervention as a solution than people realize. Business groups, for example, might clamor separately for subsidies or tax breaks.

“People think progressivism is about yelling about your views, but it’s truly about inclusion and welcoming more people,” Lee said. “To do that, you have to constantly work on persuasion.”

He added, “Some of my critics might say I only care about socialism because it is popular, but boy, do I have something to tell them: These ideas are by and large not popular, and we have to fight like hell just to make them mainstream.”

To hear Lee tell it, fixing the state’s housing crisis involves a three-legged approach. In YIMBY circles, it’s known as the “3 P’s” which stand for: protecting existing and vulnerable residents; preserving the stock of affordable homes; and producing enough new ones to satisfy demand.

Lee’s social housing bill would first create a statewide agency called the California Housing Authority to act as a public real estate developer. The Legislature would then have to scrounge for funds in the state’s fluctuating, multibillion dollar budget to provide stable funding.

Lee said tackling the housing crisis requires hitting all three elements simultaneously. AB 2584, his bill to ban corporate landlords from owning single-family homes to rent them out, for example, was meant to preserve existing housing supply.

“We’re seeing firsthand today the market is working the way it intended,” Lee said. “There’s this notion in the American mind that we can have this laissez-faire market that will take care of all of our needs, but that has never been true in this country.”

His office in Sacramento has become something of a shrine to social housing. The first image visitors see upon entering is a picture of the Lindley, a new mixed-income apartment complex spearheaded by the public housing agency (opens in new tab) in Montgomery County, Maryland.

Spread out on the coffee table are home sales brochures from Vienna, which Lee says he uses to remind people that “real estate agents still have jobs” in cities where the government is a major residential landlord.

Lee went to the Austrian capital last year with a delegation of U.S. lawmakers to study how different foreign governments approach social housing. Vienna has become something of a beacon for pro-social housing types, with 60% of residents living in city-owned flats or cooperative apartments.

Another one of his most prized possessions is a miniature model of the Pinnacle@Duxton in Singapore gifted to him after he returned from overseas—seven connected towers that make up the world’s tallest public residential buildings, complete with sky bridges and rooftop gardens.

If a left-wing government in Vienna and a right-wing one in Singapore could provide housing as a public good, then the U.S. government has no excuse, Lee argues.

“If we can’t do what they did a century ago under worse conditions, what American exceptionalism do we have?” he said.

Baring battle scars

Lee is confident and fast-talking in person. Even though he is brimming with an inventory of policy ideas, he often prefaces his arguments with a hint of self-deprecation, a bit of a defense mechanism to avoid being labeled the hotshot know-it-all.

“The lows were really low,” Lee said. “I hate politics sometimes. It can be ridiculous. But I guess that comes with any workplace.”

Now well into his second term—where he remains the youngest politician at the Capitol—Lee has something his colleagues can appreciate beyond just his precociousness: battle scars.

“I admire that Alex is so persistent,” said state Sen. Scott Wiener, who has endured more than his fair share of threats and vitriol for his identity and policy positions. “In this line of work, you get knocked down a lot, so I salute him for always getting back up and going at it again.”

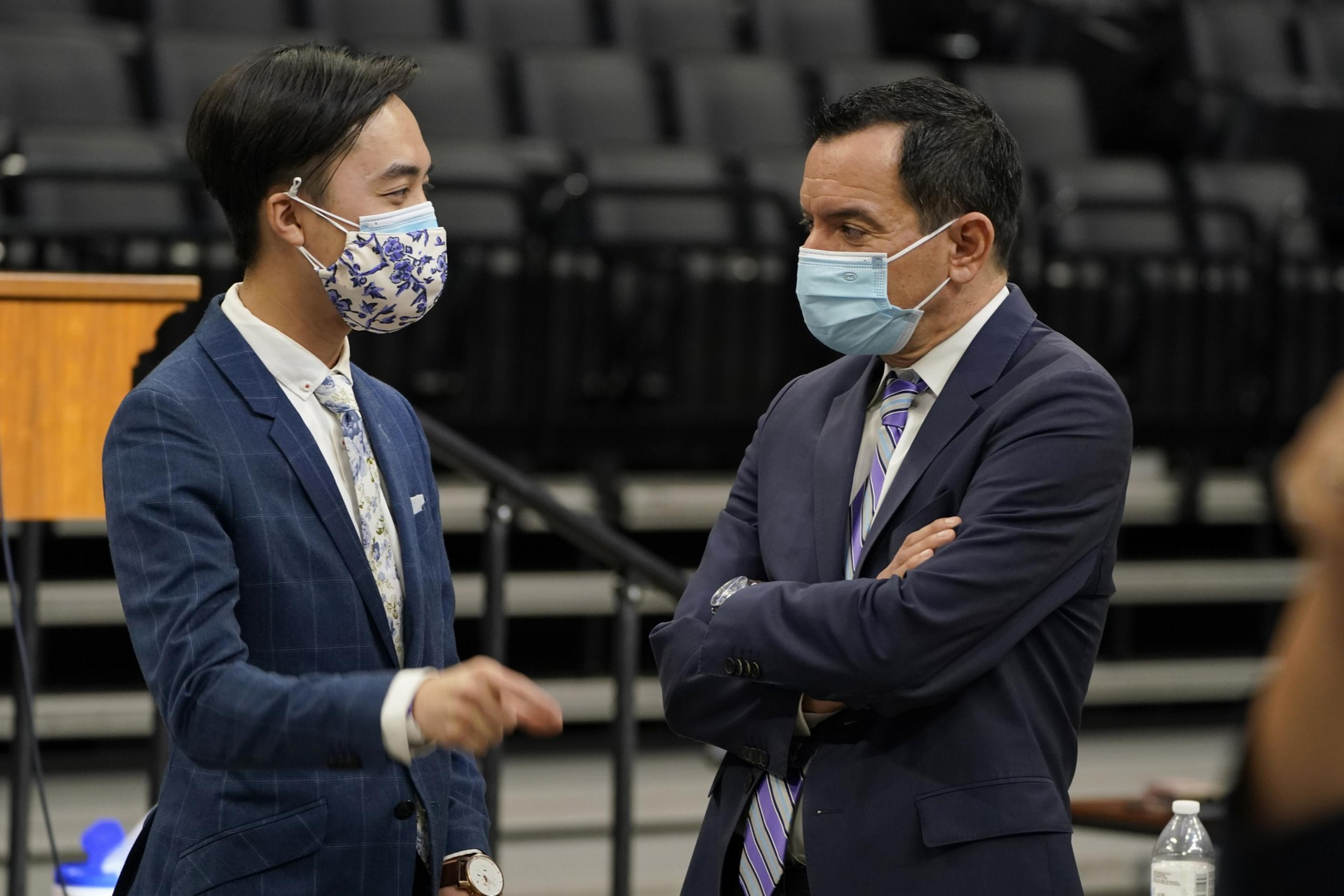

Even though they are 25 years apart in age and working in different chambers, both men have made housing the cornerstone of their agendas. Lee said it’s an issue that continues to cut across all class and ethnic lines in his district. Making it his top priority, he notes, propelled him to his electoral victory and, later, reelection despite his lack of experience.

Whereas Wiener’s camp has largely fixated on amending the existing system of zoning and permitting, Lee has chosen to revive a dormant concept of public housing that fell out of favor in American politics decades ago.

Lee believes that the government should use public funds to take on an active role as a real estate developer to build more homes where the private market falls short. He views the current moment as a prime example where high costs and interest rates have essentially frozen development across the state.

Unlike the country’s previous public housing efforts, which primarily focused on low-income households, AB 2881, would create a statewide development agency to directly build new homes across all income levels.

The idea isn’t to eliminate or block private development, but rather, create an alternative source of housing supply that is not beholden to the boom-or-bust cycles of the private sector, Lee said.

It’s his fourth attempt to pass the policy. In 2021, his first social housing bill never saw the light of day. Another version made it out of the Assembly a year later, but stalled out in the Senate. Then came Assembly Bill 309, which managed to pass (opens in new tab) through both houses (opens in new tab) of the Legislature before being vetoed (opens in new tab) by Gov. Gavin Newsom late last year.

“Big things usually take 5 to 10 years to try, but I was able to do it in two, which I’m really impressed with myself,” Lee said with a sly smile.

The final hurdle

More and more of his colleagues are warming to Lee’s ideas of social housing, as evidenced by his bill’s passage last year. Wiener, for his part, said he supported both of Lee’s previous bills and would vote for this current one, if it makes it back to the Senate.

Assemblymember Luz Rivas, who has represented the eastern part of Los Angeles County since 2018, said the evolution of his social housing bill is a representation of Lee’s journey as a lawmaker thus far.

“I have watched Alex shift his ideas, which many of my colleagues dismissed because they were unfamiliar or too aspirational, into viable policy,” Rivas told The Standard. “He has developed relationships with legislators and leaders regardless of whether they share his ideological views.”

But all roads lead back to the governor’s desk. In his veto last year, Newsom cited concerns about costs and the potential repeating of efforts already put in place by existing affordable housing policies. Lee said he’s still sorting out the best way to win over the state’s top executive.

“The governor and his crew are interesting people,” Lee said, coyly, about his conversations with Newsom’s office. But he added the governor was practical and pragmatic when discussing housing crisis solutions.

In a place where business or political interest groups can steer policy, Lee said the majority of his ideas come from “the crazy mind of Alex Lee.” He relishes carrying the progressive torch. After winning reelection, Lee was named chair of the Assembly’s progressive caucus and Environmental Safety and Toxic Materials Committee.

He also makes no secret that he idolizes both Bernie Sanders (who endorsed him in both elections) and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, whose autographed business card is framed and prominently displayed in his office.

The pair have placed social housing at the center of their latest Green New Deal proposal (opens in new tab).

When the “low lows” of politics have him feeling down, Lee, who wants to serve out the entirety of his potential term until 2032, said he draws inspiration from someone like AOC, who deals with greater and louder opposition than he does.

“I still do get imposter syndrome from time to time,” Lee said. “But I’ve been in enough rooms now where people older than me have no problem saying things super misinformed. I have to remind myself that if I’m going to go through the trouble of educating myself, that I should be taking up that space.”

Correction: This piece has been updated with the number of times Alex Lee has tried to pass a social housing bill.