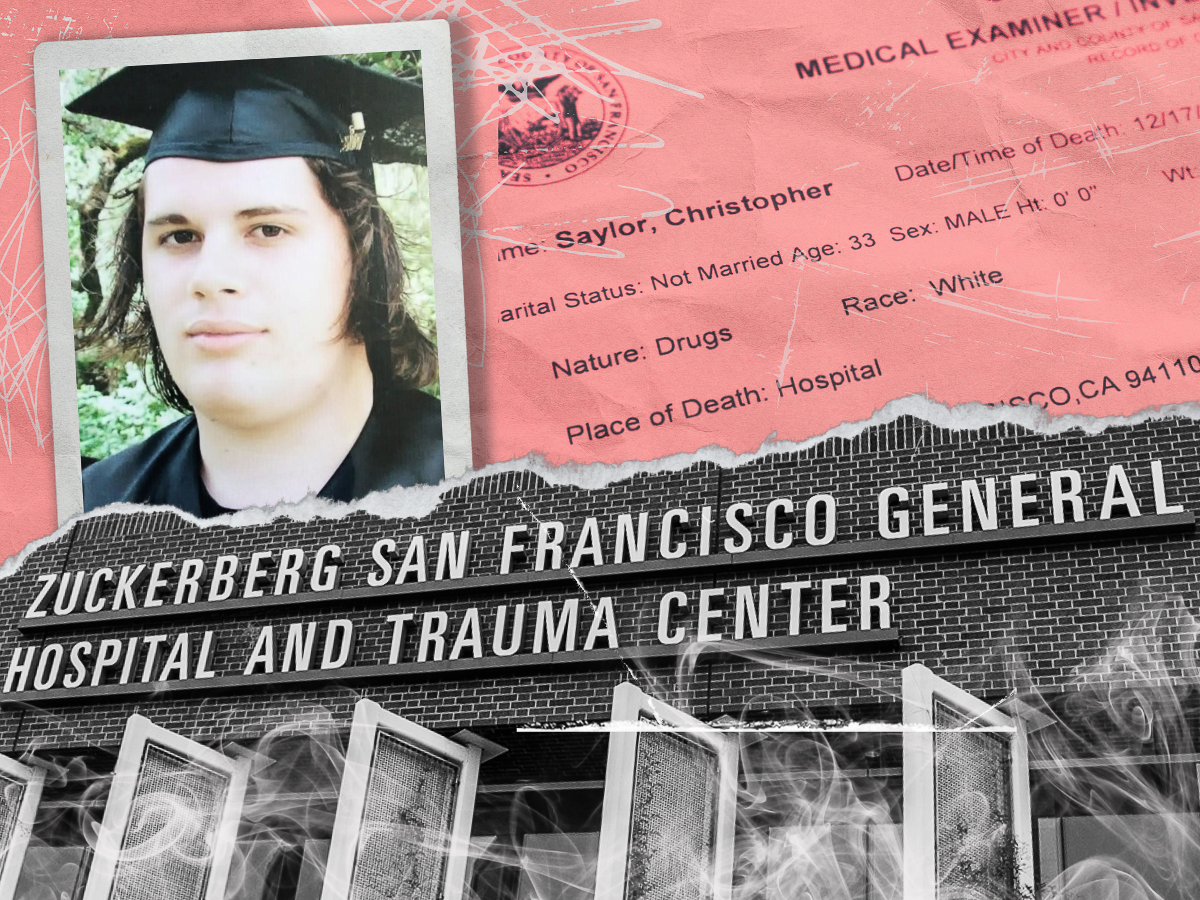

In the days before her quadriplegic son Christopher Saylor died, Barbara Scholes remembers telling staff at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital to confiscate his drugs.

She even told them where the 33-year-old hid his stash, she recalls. He was mostly paralyzed from the neck down after a bike accident in 2020 and kept his drugs in a little red box that hung around his neck.

Nurses first found Chris high on fentanyl in the hospital the day before his death. But he “refused a search of his belongings,” and staff continued prescribing him oxycodone, a highly addictive opioid, according to a death report obtained by The Standard.

At around 4:30 a.m. on the day of his death, Dec. 17, 2022, a nurse found him lying next to a lighter, a burnt piece of tin foil, a straw and “white powder.” Again, he “refused all care unless it was to provide fentanyl,” and the nurse left the room.

Just 30 minutes later, nurses found him dead from an overdose.

When his mom arrived at the hospital that day, the nurses gave her Chris’ belongings; among them was his little red box—with a lump of fentanyl still inside, she said.

“What a freaking joke,” Scholes told The Standard, holding back tears. “They gave me his possessions, and there was the red box. I opened it up, and sure enough, there it was.”

Scholes said she believes if the hospital had confiscated those drugs, her son may still be alive.

“You don’t check them for drugs when they’re known drug users?” she said. “That’s pretty stupid.”

Drug-free zone?

Scholes’ concerns about her son’s death echo those of nurses at the hospital, who have decried drug use inside San Francisco General Hospital, which they say endangers their lives and jobs.

Nurses worry that incidents like Chris’ death put their medical licenses in jeopardy. Last March, a nurse was hospitalized after coming into contact with drug smoke inside a hospital bathroom, suffering an apparent panic attack.

“We don’t have the mechanisms in place to remove drugs from people,” said Heather Bollinger, an emergency room nurse at the hospital. “If this was your family member and they were in the hospital, you would be like, ‘Why are you allowing them to do this?’”

But the answer to the issue isn’t straightforward, Bollinger said. Confiscating drugs from a patient suffering from addiction and mental illness can sow distrust in the medical system, leading patients to refuse care while languishing on the city’s streets.

Hospital administrators contend that drug use is prohibited on hospital grounds and that it has a rigorous safety program in place. However, nurses say they lack the guidance to carry out the prohibition policy.

The hospital said drug users are given the option to dispose of their substances, but did not elaborate further when pressed to answer questions about whether staffers can seize illicit drugs from patients.

That said, Bollinger believes there are gaps in the city’s health care system that make it difficult to treat patients with severe addiction. She’s often unable to locate detox beds for patients when they’re discharged, she said.

“We have an ideology that we really want to support, but we don’t have the resources in place to make it successful,” Bollinger said. “Now we have a patient who can’t get what they need, and we have a nurse who’s at risk.”

San Francisco General Hospital told The Standard that its policy on substance use and prevention “is being strengthened.” The hospital said it thoroughly investigated Chris’ death but didn’t contact state or federal authorities because it wasn’t necessary.

‘How did he light the lighter?’

The circumstances of Chris’ death, which have only now come to light through public records obtained by The Standard, are raising questions for his family about why the hospital didn’t take his drugs away.

Scholes said she considered taking legal action after his death but couldn’t afford a lawyer.

Meanwhile, his father, Richard Saylor, had other questions.

“He had no use of his hands; how did he light the lighter?” Richard said. “Somebody had to have lit it for him.”

Chris had a long history of substance abuse that became worse once he was indefinitely hospitalized inside Laguna Honda Hospital following his accident, Scholes said.

“The doctor told him he had zero chance to walk ever again, so they stopped doing therapy,” Scholes said. “They dashed the dude’s hope.”

Federal regulators almost pulled funding from Laguna Honda Hospital after two people overdosed there in 2021. A Laguna Honda spokesperson said the use, possession, and distribution of substances are strictly prohibited.

Scholes said that while he was a patient at Laguna Honda, Chris found a way to use the side of his thumb and his mouth to spark a lighter. She said he could move his arms but his hands were permanently balled into fists.

The day before he died, Chris told staff at San Francisco General Hospital that a “visitor” had brought him fentanyl. Scholes suspects this visitor was likely a drug dealer.

She remembers her son, known affectionately by his friends as “Crazy Chris,” for his sense of humor and his generosity. Richard said his memorial service was flooded with people.

“He was always funny, joking around. Always trying to help,” she said. “Then he started using drugs, and my God.”