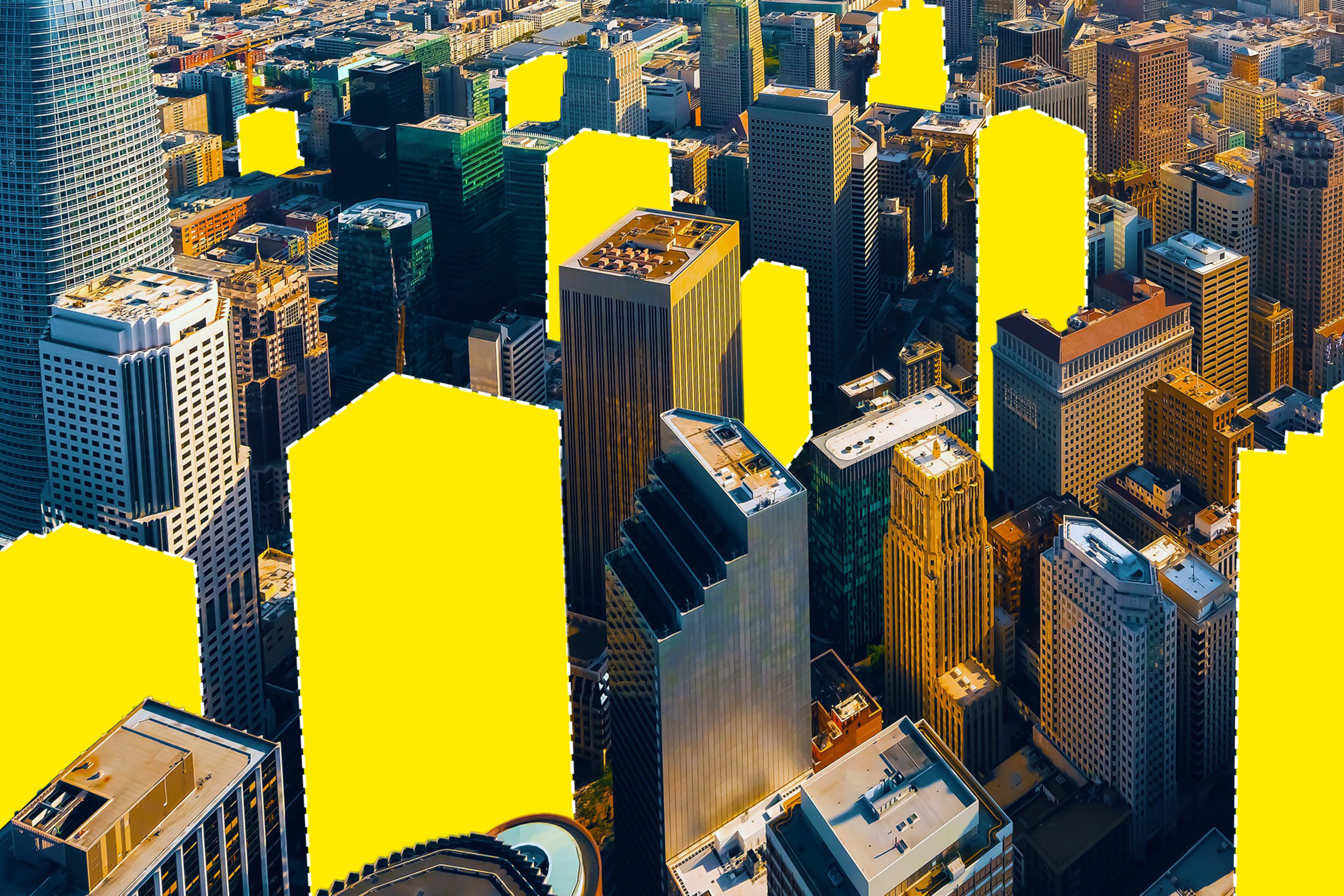

In the 2010s, blue-chip tech firms like Uber, Airbnb, Dropbox, Meta and Salesforce spent hundreds of millions of dollars opening glamorous, amenity-filled offices in downtown San Francisco, spurring a building boom that altered the city’s skyline.

After a global pandemic and a wholesale shift to hybrid work, those same firms have retreated en masse—leaving the city’s now hollowed-out downtown to pay the price.

By the end of 2019, the 20 biggest tech employers had leased more than 16 million square feet of space, nearly a quarter of the city’s total office stock. Now, those same companies are holding onto only 8.3 million square feet, according to data from real estate firm CBRE.

“Tech companies were the most important as it was related to growth, but they’re also the most responsible for the downsizing as well,” said Colin Yasukochi, executive director of CBRE’s Tech Insights Center.

What drove the city’s previous real estate boom has now busted. And there’s still no clear answer on what comes next.

‘Everyone is splitting’

Even with the recent pickup in office leasing from nascent industries like artificial intelligence and climate tech, the scale of Big Tech’s pullback dwarfs the total leasing activity over the past two years.

“We’ve just gone from being at the most amazing frat party to now the police have arrived and everyone is splitting,” said a veteran San Francisco tech office broker who asked to be anonymous to preserve existing client relationships.

A few key examples: Last January, Meta listed all 34 floors, or 435,000 square feet, of its office space at the glitzy 181 Fremont skyscraper for sublease after announcing mass layoffs tied to cost-cutting efforts. A company spokesperson confirmed Meta kept one office location in the city at 250 Howard St., where it still leases all of the office space at the 43-floor tower.

Uber followed Mark Zuckerberg’s lead and put a portion of its massive Mission Bay headquarters campus up for grabs months later, with two buildings eventually snapped up by OpenAI last October.

The city’s largest private employer, Salesforce, said in a recent securities filing that it now owns or leases less than 45% of office space it had from the year prior—about 900,000 square feet, down from 1.6 million, as of last January. “Our offices remain a critical part of our culture here in San Francisco, our global headquarters, and around the world,” a Salesforce spokesperson said in a statement.

Data from Avison Young shows that, among the top 20 tech companies in San Francisco based on office space in 2019, at least four have completely eliminated their office footprint, with one company reducing its space by over 730,000 square feet. Another company, which still has offices in the city, reduced its space by more than 1 million square feet. Overall, 80% of these companies have decreased the amount of office space they use in the city.

Before the pandemic, Big Tech occupied the best spaces while paying top-tier rents, real estate experts said. Derek Daniels, regional research director for Colliers, said the combination of low interest rates and the explosion of cloud computing, social media and other technologies drove the previous boom.

“With expectations of continued growth in funding and headcount, some were even committing to proposed [but unbuilt] sites,” Daniels said.

Now, the dynamic has been completely flipped and companies in the market for San Francisco office space do not lack options. Colliers estimates that nearly 30% of offices are currently vacant. Other firms tag the number as high as 36%.

Put in physical terms, some 30 million square feet remain empty. As a visual aid, that’s the equivalent of more than 500 football fields of space or more than 20 Salesforce Towers.

The slowdown doesn’t appear to be reversing quickly. Revised data from the state Employment Development Department last month showed that the tech industry is still in the midst of shedding jobs after an already painful year defined by layoffs.

Waiting for the reset

Since most office buildings are tied to a commercial loan, distressed landlords not collecting steady rent checks have either had to walk away from properties or sell at a steep discount. Only once that cycle is completed—and pre-pandemic rates flushed out—can rent costs finally be reset, experts say.

Take the 22-story office building at 350 California St. as a model. In September, San Francisco real estate developers SKS Partners and the Swig Company partnered to purchase the property for around $61 million, roughly 75% off the price it went for in 2020.

With a lower cost burden, the new landlords were able to ink two new office tenants that likely wouldn’t have been able to afford the location previously. In January, nonprofit developer Bridge Housing nabbed the entire 16th floor, while climate innovation coworking company 9Zero took the fourth floor days after.

Similarly, the City and County of San Francisco announced it was exiting its lease from 1155 Market St. last month in favor of a discounted deal and newer digs down the street at 1455 Market St., the former home of Uber and Block.

Whereas the last run on real estate was driven by unicorn startups and Silicon Valley giants, the biggest office leases so far this year are from less-flashy companies taking advantage of lower rents to accommodate their growing headcounts.

Dutch payment processing company Adyen snapped up Pinterest’s entire building at 505 Brannan St. in February, while HR automation software company Rippling just leased nine floors at 430 California St., once entirely occupied by WeWork.

Meanwhile, with the larger tech industry in retreat, all eyes are fixed upon AI to take the torch. Real estate sources said last week OpenAI is still shopping for more office space despite recently expanding its footprint.

JLL Senior Analyst Chris Pham said while the focus has been on the large-language model AI companies, the potential for growth in the next few years will come from those who build applications on top of those models, likening them to “the next Uber and Facebook.”

Citing PricewaterhouseCoopers estimates, Pham’s team estimates that AI companies will lease up to 12 million square feet in San Francisco by 2030.

But it’s best to keep expectations tempered, others say. AI is still a part of a larger industry going through an existential realignment.

“The current tech turnaround will take a few years to broaden into a much larger growth cycle,” Yasukochi of CBRE said. “Tech still has the highest growth potential for San Francisco since financial and legal have been declining in employment for decades.”