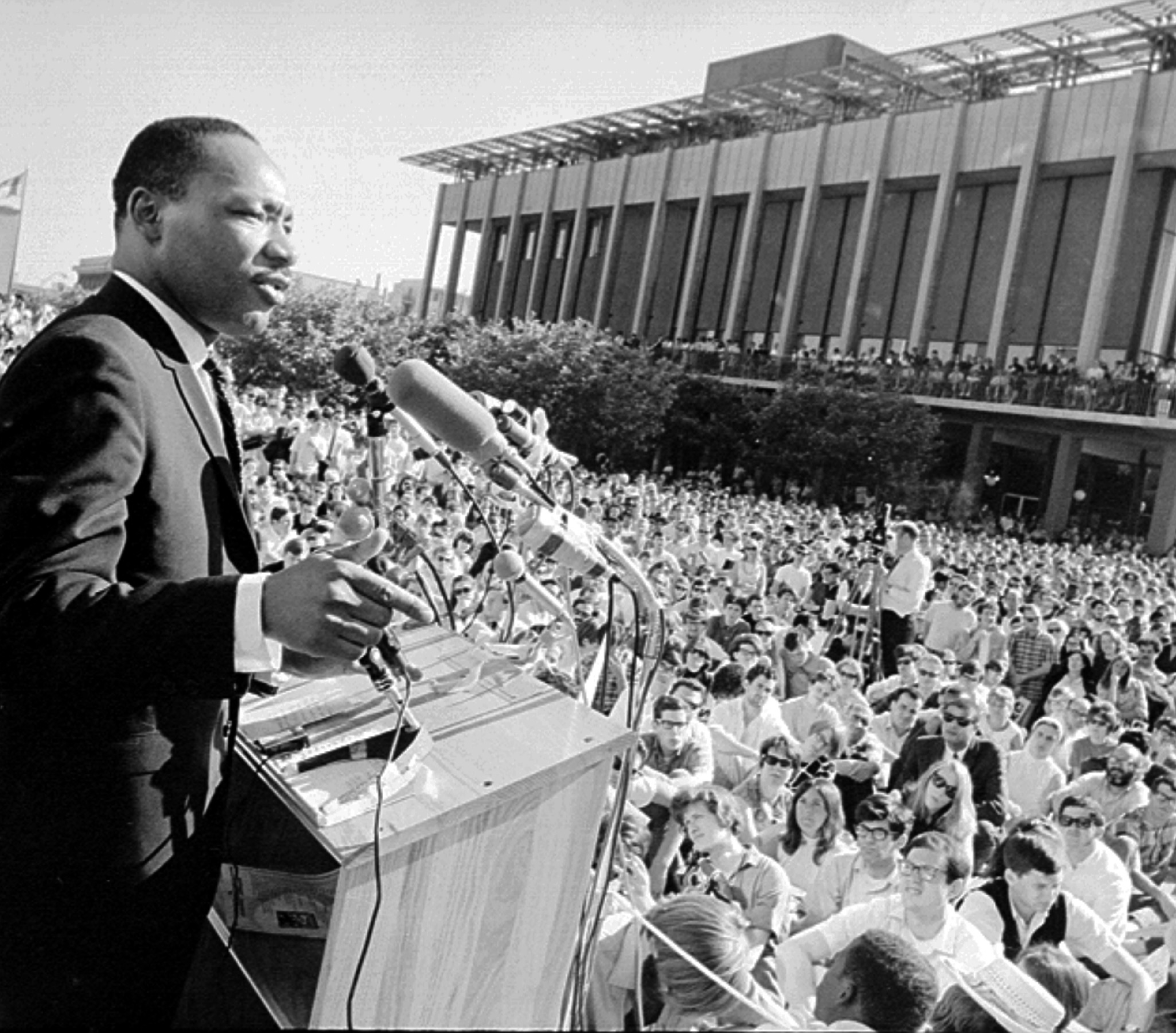

The broad steps leading to Sproul Hall at UC Berkeley, where Martin Luther King Jr. and Mario Savio once exhorted young students seeking justice, are currently covered by tents, occupied by students furious about Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza.

It is a festive atmosphere, with students sitting and talking, working on their laptops and grazing from a table loaded with donated food. Students from Jewish Voice for Peace held a Passover seder one night last week. There are daily teach-ins calling attention to the war, and the U.S.’s role in it. Muslim women wear headscarves, and Jewish men don watermelon kippahs—an agricultural symbol of the Palestinian cause. Many of the protesters have patterned keffiyehs around their shoulders. Others sport political T-shirts, including a group of recently fired Google workers who showed up to offer support, wearing black shirts denouncing the company’s Project Nimbus contract with Israel.

What there isn’t on the Savio Steps is violence, or police action. There is tension at UC Berkeley, but it is nothing compared to the turmoil roiling campuses from USC to Columbia University to Ohio State, where frenzied scenes of police arresting protesters and taking down tents are increasingly common.

Why has a tense but steady calm held at Berkeley—a famous cauldron of protest and uncalm—while a sometimes-violent uproar has overtaken so many other universities across the U.S.?

The answer, in part, may lay in the University’s decision to stand pat, and let the encampment remain where it sits, at the entrance of the 45,000-student campus. The hands-off approach reflects the lessons Cal administrators learned after they mishandled a 2011 protest.

On Nov. 9 of that year, hundreds of students linked arms in front of the Savio Steps to defend a small tent encampment set up by students to support the Occupy movement. UC Berkeley police declared an unlawful assembly, and when students didn’t disperse, police shoved truncheons into protesters’ stomachs to push them back. The chancellor at the time later apologized for how the police handled the situation.

That led to the school’s current non-escalation strategy. The university allows protests if they don’t block doorways or thoroughfares or disrupt teaching, learning or research, said Dan Mogulof, an assistant vice chancellor of communications and public affairs. University policies prescribe intervening only if an assembly becomes violent or poses a clear and present danger of violence.

But while the atmosphere at Berkeley is placid at the moment, there are signs, literally, that the center may not hold. The UC Berkeley Divest Coalition, the encampment organizers, says it represents 7,000 students. However, signs near the encampment make it clear that supporters of Israel are not welcome. At a Monday rally, protesters chanted, “Say it loud, say it clear, we don’t want no Zionists here.” Someone scrawled “anti Zion(ist) Zone,” in chalk on Sproul Plaza.

The Berkeley organizers say they will stay on Savio Steps until the university acknowledges there is a genocide happening in Gaza, agrees to divest from companies that do business in Israel and closes its student program there, among other demands.

“We’re willing to risk suspension,” said Malak Afaneh, a third-year law student, co-president of Law Students for Justice in Palestine and a Palestinian American who believes a Palestinian state should replace the country of Israel. “We’re willing to risk expulsion; we’re willing to risk arrest. We’re willing to risk anything to stand here until we achieve our demands for divestment.”

“This is a different kind of protest”

The October attack on Israel, in which Hamas militants murdered 1,200 people and took 240 hostages, and Israel’s subsequent retaliation against Hamas in Gaza, which has led to starvation, mass death and the decimation of cities, has roiled UC Berkeley like no other issue in the last 20 years.

“This is a different kind of protest,” said Mogulof. “Past protests, whether against the Vietnam War, during the Free Speech Movement, or anti-apartheid, didn’t divide the campus community. We didn’t have a situation of student on student, faculty member on faculty member.”

“The climate on campus is difficult,” said Ethan Katz, an associate professor of history and the faculty director for the Center for Jewish Studies. “It’s the most difficult we’ve seen in a long time.”

Some of the tension stems from how pro-Palestinian protesters frame the war in Gaza. They don’t just blame Israel’s right-wing government but the philosophy of Zionism and, by extension, Jews who support Israel as a homeland. This strategy was conceived in 1993 in a cafe on Durant Avenue just steps from Sproul Plaza. About ten Muslim and Palestinian students, including Hatem Bazian, who is now a lecturer at Cal and who spoke recently at the encampment, opposed the recently signed Oslo Accords that set a path for Palestinian self-governance (but not a new state).

The group set out to redefine the conflict by arguing Israel was an apartheid state and that the Palestinians who had left or been expelled during the 1948 war had a right to return to their homes, Bazian has said. Students for Justice in Palestine grew out of that meeting, and it is now among the most prominent pro-Palestine advocacy groups in America.

But the idea that individual Jews who support Israel can be held accountable for the war in Gaza is a hazardous one. And it has led to at least one attack on Jewish students that UC Berkeley police are investigating as a hate crime.

On Feb. 26, Ran Bar-Yoshafat, a former member of the Israeli Defense Forces, was scheduled to speak at Zellerbach Playhouse. Bears for Palestine, a student group, urged its followers on Instagram to shut the event down, writing that Bar-Yoshafat, who fought in Gaza, “has Palestinian blood on his hands.” About 200 pro-Palestinian protesters marched through campus and swarmed the entrance to the hall. They chanted and banged on the glass, breaking a door and frightening those inside. At least one protester got inside, spat on a Jewish student, and allegedly said, “You dirty Jew.” Police canceled the event and rushed the speaker and organizers out a basement door. No arrests have been made yet. Bar-Yoshafat spoke without incident a few weeks later.

This was the most high-profile anti-Jewish attack on campus, but there have been other difficult moments for Jewish students. For weeks, pro-Palestinian students stretched banners or yellow police tape across the main section of Sather Gate, impeding but not blocking a major thoroughfare on campus. They broadcast recordings of bombs dropping and people screaming. Some protesters told Jewish students they had “blood on their hands.”

After Ron Hassner, a political science professor, held a sleep-in in his office for almost two weeks to protest what he saw as the administration’s insufficient protection of Jewish students, the university posted observers at Sather Gate. The atmosphere, and reports that Israeli flags were ripped from the hands of at least two Jewish students, prompted the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce to launch an investigation (opens in new tab) into how the university is responding to antisemitism incidents and other issues.

On the other side, some Muslim students who support Palestine and denounce Zionism have been doxxed, or had their personal information put on the web and social media. Canary Mission, a right-wing organization that exposes personal information on individuals that they brand as hating the U.S. and Jews, has lengthy entries on at least 16 UC Berkeley students, including one on Afaneh, one of the people who promoted a 2022 law school resolution banning Zionist speakers.

She achieved national attention in recent weeks when a video of a confrontation she had on April 12 with Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean of the law school, and his wife, law professor Catherine Fisk, went viral. Earlier that week, Law Students for Justice in Palestine posted a flyer depicting a caricature of Chemerinsky holding a bloody knife and fork with blood around his mouth. The image invoked the trope of blood libel, a Middle Ages myth that Jews killed Christian children to extract their blood for Passover matzos.

During a private dinner at Chemerinsky’s house in Oakland to celebrate the graduation of third-year students, Afaneh, stood up with a microphone she had brought to the dinner and started to speak. Afaneh only said a few words about Ramadan before Chemerinsky and Fisk asked her to stop. When she didn’t, Fisk tried to grab the microphone from Afaneh, prompting the student to talk about UC’s role in funding weapon manufacturers. The dean wrote about the incident this week in the Atlantic, under the headline “No One Has the Right To Protest in My Home (opens in new tab).”

Meanwhile, concerned about Islamophobia, the Associated Students of the University of California, the student governing body, adopted a measure recently condemning “all acts of discrimination, harassment, or intimidation against Palestinian students or any student based on their nationality or political beliefs.”

Business as usual at the Free Speech Café

While the protests grab headlines, most of the 60,000 people who are on campus every day seem unaffected. Recently, members of the Armenian Students Association set up a tent in front of Doe Library to call attention to the 1915 massacre, when Ottomans killed and starved 1.5 million Armenians. A stream of visitors stopped to purchase gata, a popular Armenian pastry.

Tatev, 20, a senior, who asked that her last name not be used, said the group set up far away from the pro-Palestinian encampment on purpose. They were concerned that students would confuse the two genocides if they were publicized side by side.

“A lot of Armenians are sympathetic to the Palestinian cause and vice versa,” she said. “We know what it’s like to be the only ones rallying for their cause.”

At the nearby Free Speech Movement Café, whose entrance is bordered by exhibits of that day’s front pages from around the world, it was business as usual. People stood in line to order coffee and food. Almost all of the tables were occupied. One third-year student reading on her iPad said she hadn’t participated in any protests. She and her friends are not political, but she was glad the encampment was happening as it reinforced Cal’s reputation as a bastion for free speech, she said.

A staff member eating lunch under the campus’s 307-foot-tall landmark, the Campanile, had a more cynical view. Asking that his name not be used, he predicted that none of the demands of the pro-Palestinian protesters would be met. There are so many demonstrations on campus each year that the university is inured to them. The administration doesn’t listen to students, he said. They listen to donors.

Can protesters maintain this uneasy peace? What happens at semester’s end, when organizers promise the encampment will persist, despite an exodus of students? Like a shadow of the war itself, the ultimate resolution at Berkeley, and on campuses across the country, is entirely unclear.

Correction: This story was updated with the proper spelling of Berkeley Law student Malak Afaneh’s name.