Tin Nguyen used to have two roommates. Now, he has thousands.

Both floors of his San Rafael home hum with large saltwater tanks, each filled with hundreds of coral specimens, along with angelfish and clownfish and other species that swim around Nguyen’s homegrown colonies.

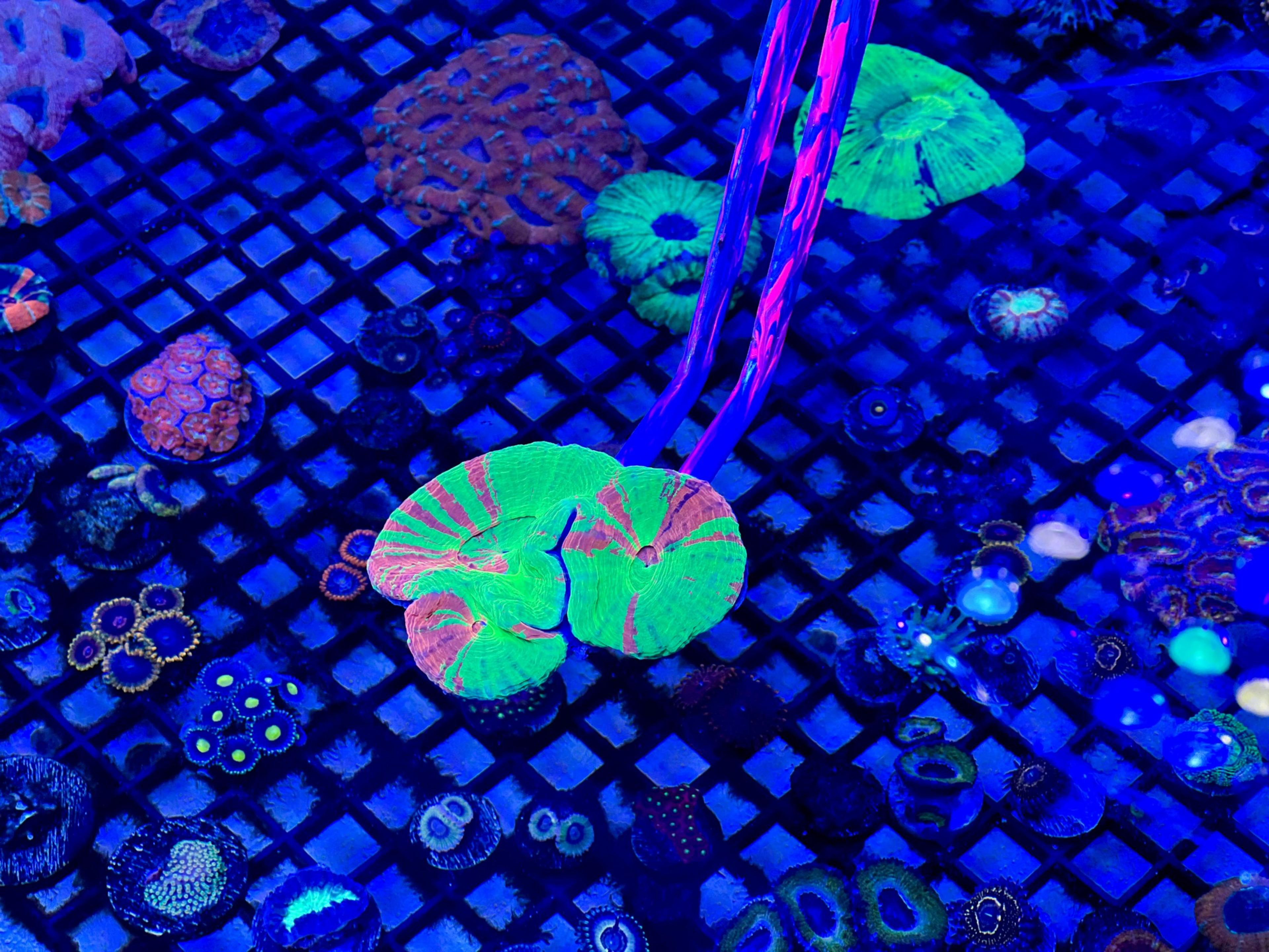

There are two tanks in the dining room, two bigger ones in the living room, another three in a spare bedroom upstairs and one in the bathroom—so when he turns on the blacklights, the house feels like a collection of neon underwater raves. Beyond all the marine invertebrates is one other mammal: a gregarious pitbull-Chihuahua mix named Phoebe, who doesn’t seem to mind the ultraviolet glow.

A self-described “reefer” and lifelong Marin resident, Nguyen has been interested in the life aquatic since he took home his first goldfish in a plastic bag from an elementary school fair. He owns a computer repair shop elsewhere in San Rafael, but over the last 15 years, coral farming has gradually overtaken his life. Now he’s on the cusp of making this increasingly lucrative side hustle his main gig, selling tens of thousands of dollars worth of homegrown reefs at various coral-fanatic conferences and trade shows around the country.

When he spoke with The Standard earlier this month, Nguyen had just returned from Reefapalooza, a two-day expo in Orlando (opens in new tab) that bills itself as America’s largest saltwater aquarium show and where he sold $22,000 worth of coral—his most ever.

“This is the Holy Grail,” he said, pointing out a specimen of hulk torch, an anemone-like beauty with rounded tentacles that glow the color of bananas and would administer a mild sting to anyone who touched it. “Everybody wants a yellow coral, which is the most rare. This is like the Holy Grail of Holy Grails, because it’s extra-yellow and extra-long.”

It’s about 8 years old, although Nguyen has only owned it for the last four months. The cost? A tidy $1,300. “That’s actually a deal, because it has two heads on it,” he said, referring to the distinct colonies growing side-by-side. “Normally, one head goes for $1,000.”

That’s nowhere near the highest price that corals command, either. “Bounce mushrooms were the hottest item in the hobby a couple years ago,” Nguyen said. “You see little bubbles on them. And the bigger the bubble, the better. Some of them can reach 10 grand—not because of its age or anything, just its color variation.”

‘It’s magical water’

For hobbyists like Ngyugen, the propagation of coral is an attempt to harness nature while the oceanic world is going in the opposite direction. Worldwide, coral reefs are losing their colors as carbon dioxide emissions cause the ocean to become hotter and more acidic, leading to a phenomenon called “bleaching.” (Bleaching doesn’t necessarily mean the coral is dead, just that it’s expelled the zooplankton that provide both nutrients and those distinct hues.) Reefers’ home tanks, then, are almost like little versions of Noah’s Ark, keeping their specimens healthy and bright—although instead of rounding them up in twos, they buy and sell them in great numbers.

According to Matt Wandell, husbandry operations project manager at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, some institutions in Florida or around the Caribbean replant farmed coral to help repopulate bleached or dead reefs. California’s aquariums, not so much.

“We don’t keep any corals that are endangered or even threatened,” Wandell said. “It’s mostly for visitors to think about conservation. … We have an open system of seawater, so it means we’re constantly bringing water in. And it’s magical water.”

That magical water yields some mesmerizing results. Whether shaped like a torch, a fan, a blob or a brain, corals are clusters of genetically identical animals that secrete calcium carbonate exoskeletons, which are what form a coral reef, and reproduce both sexually and asexually. They grow off the skeletons of their predecessors and use the phases of the moon to release their reproductive cells into the ocean—the romantic goths of the tropics, in other words.

Most of the 50 or so species Nguyen farms come from Indonesia or Australia. They often have fanciful names that call to mind theatrically costumed wrestlers (raja rampage chalice) or novelty cocktails that dare you to drink them (Bali green slimer).

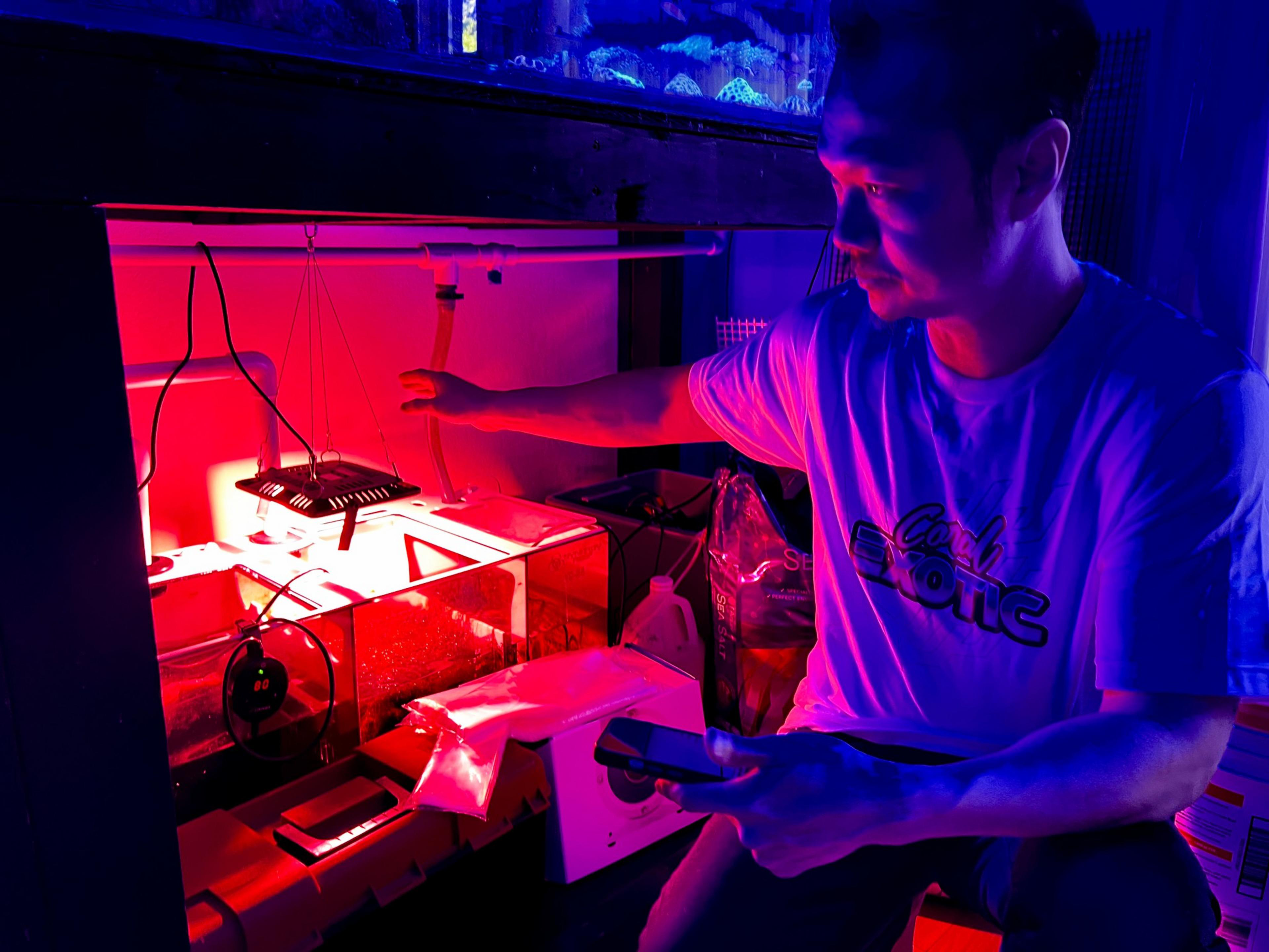

Most collectors favor large sizes and bright colors, while many reefers also look for species that grow quickly and happily. Not unlike fussy pandas that struggle to breed in captivity, coral gets stressed easily. The chemistry of Nguyen’s home ecosystems is largely automated, his equipment testing for pH, phosphates, nitrates, iodine levels and other factors.

Most maintenance can be tweaked on his phone, and the rest he leaves up to nature. Take the sea urchin that lives in one tank. Right now, it’s sequestered in a basket, like a combative hockey player in the penalty box.

“I put them in to eat the algae, but he started eating the coral,” Nguyen said. “So I had to isolate him. When the algae grows back, I’ll bring him out. It’s like a Roomba.”

According to friend and fellow reefer Trish Legleva, Nguyen has a reputation for calm. “He’s known as an ‘acan’ guy,” she said, referring to Acanthastrea, a genus that looks like dried apricots. “A lot of people don’t have patience for it.”

Nguyen identifies more as a “scoly” guy, referring to the mushroom-like Scolymia. Until recently, they were only collected in the wild because no one could figure out how to grow them. “The hobby is advancing science,” he said. “Hobbyists, we know more overall than marine biologists.”

Wandell says that growing corals at home is a “fantastic way of doing things,” in spite of the learning curve and technical challenges. “They’ll start with something the size of a dime and grow it into this massive colony the size of a coffee table,” he said.

All for more beauty

Most of what Nguyen buys, sells and trades is local. Three times a year, he goes to the Silicon Valley Coral Farmers Market (opens in new tab) in Santa Clara (the most recent gathering was this past weekend). Driving with styrofoam boxes full of delicate coral isn’t particularly cumbersome; flying is another matter entirely. Nguyen has to hand-pack every coral fragment (“frag”) in its own individual bag with a protective cup so it doesn’t get knocked around too hard, then place that in his luggage.

It took him six hours to pack for Orlando, and he has to time the process so that he finishes at exactly the moment when he leaves for the airport. Then there’s the weight restrictions. Packing five bags that each weigh no more than 50 pounds is as tricky as it is expensive. So he flew to Florida with Leglava and another reefer friend, putting bags in their names.

The conferences are lucrative, but they’re also where reefers share their hard-earned wisdom. Nguyen only recently learned the mechanics of a new reefing method called “moonshining,” where growers achieve peak performance by obsessively fiddling with every single element in their water chemistry, even if it requires waking up in the middle of the night to add a droplet of this or that reagent.

“If coral’s not that happy, it’ll get pale or get dark. But when it’s happy, you know it,” Nguyen said. “They reward you with brighter colors and more beauty. More beauty: I think that’s what everybody’s chasing.”