Robert Troke was biking full speed through Nob Hill when the passenger in a parked car flung her door open in front of him.

“All I did was scream,” Troke said.

With no time to react, he slammed into the open door. He flew forward, smashing his head into the window.

Troke walked away from the crash with a damaged bike and a sore neck, shoulder and chest. For many who have gone through a similar experience, the outcome has been far worse.

Dooring—when a vehicle driver or passenger causes a collision by suddenly opening their door into the path of a cyclist—is one of the top causes of biker injuries in San Francisco. According to city logs (opens in new tab), doorings were the second-most common cause of bicyclist-motor-vehicle crashes that resulted in an injury from January 2014 through March 2024. At 416 incidents, that represented 10% of the more than 4,230 bicyclist-motor-vehicle injury crashes during that time period. (The top cause of injury crashes was drivers making an unsafe turn or prohibited lane change, which resulted in 651 incidents.)

Doorings can be fatal.

In 2019, Tess Rothstein was killed by a box truck in SoMa after reportedly swerving to dodge an opening car door (opens in new tab). The next year, a man died just outside Golden Gate Park after a person in a parked car opened their door, hitting the cyclist and throwing him into oncoming traffic (opens in new tab).

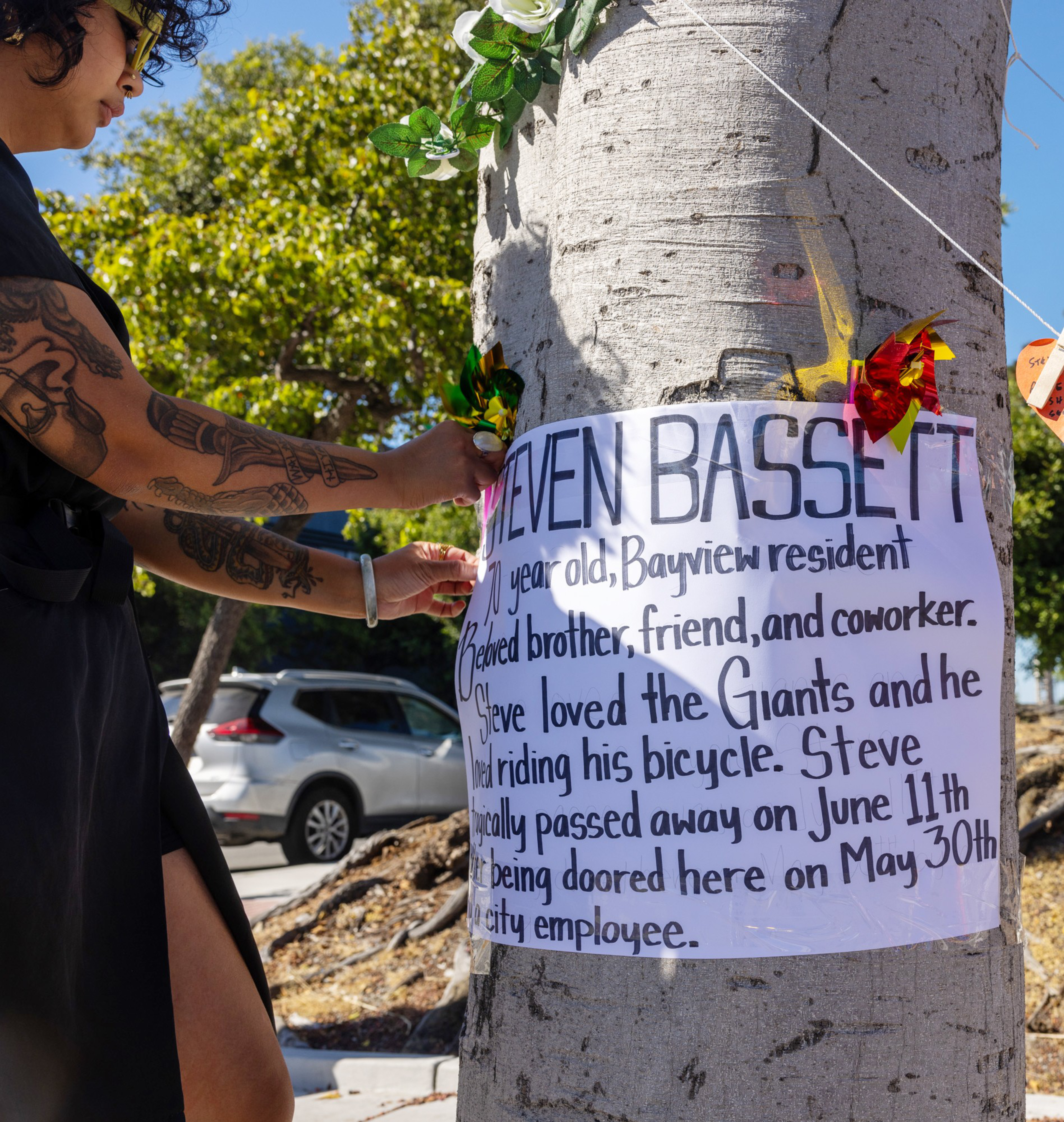

And earlier this year, there was another high-profile fatality. In May, longtime cyclist Steven Bassett died after colliding with the driver-side mirror of a San Francisco Public Utilities Commision F350 pickup truck, according to the agency’s collision report on the incident. (The SFMTA report (opens in new tab) on the incident said that the cyclist struck the open car door.)

Bassett’s death happened at a complex moment in San Francisco’s yearslong push to make cycling in the city safer. On one hand, the city has made a dramatic investment in bike infrastructure in recent years. Between 2020 and 2024, the city nearly doubled its miles of protected bikeways, recently reaching 52 miles (opens in new tab).

Likely as a result, street conditions are getting safer. San Francisco’s traffic crash data shows that the number of doorings has dropped dramatically in recent years. From 2014 to 2019, San Francisco officials logged an average of 55 dooring injuries each year. From 2020 to 2023, that number was down by more than half, to 22.

The reduction in doorings coincided with an overall improvement in cyclist safety citywide; the annual average number of bicyclist-motor-vehicle traffic crashes decreased by 31% between the years leading up to 2020 and the years since.

But while many San Franciscans have begun to glimpse the bikers’ paradise advocates have dreamed of for years, others remain in neighborhoods that have not yet seen the bike lane renaissance. That leaves cyclists hugging the side of the road, which allows them to avoid traffic but puts them in striking range of car doors.

That’s the case in much of the Bayview, where the Bassett crash happened.

Bassett was riding north from his Bayview home at Quesada Avenue and Third Street to the downtown law firm where he worked on the morning he collided with the city truck, according to a friend of the cyclist.

Biking north-south has long been fraught in the Bayview.

“Few San Francisco neighborhoods have such constrained route options without dedicated space provided to bikes,” SFMTA officials wrote in its 2020 transportation plan for the Bayview (opens in new tab).

Many of the conditions described in that 2020 report remain in place today. The city’s designated north-south bike route through the Bayview is still Third Street (opens in new tab), which is a bustling thoroughfare that doesn’t have a dedicated bike lane. While the neighborhood’s transportation plan does call for some investment in bicycle infrastructure, it’s far short of the reformation that has taken place in some San Francisco neighborhoods, like SoMa, which now have a connected network of protected bike lanes.

SFMTA has purposefully moved slower to implement transportation changes in the Bayview than other neighborhoods, according to the agency’s director, Jeffrey Tumlin. That’s because the historically Black neighborhood has a history of government imposing decisions upon residents rather than working with them collaboratively. The department aims to change that trend, but bringing in community feedback takes time.

“You can only go at the pace of agreement,” Tumlin said.

San Francisco’s history of displacement has made agreement on bike infrastructure more difficult to reach. The city’s early attempts at bike share programs came to symbolize gentrification (opens in new tab), as people perceived the program as aiming to service young professionals rather than longtime locals. In 2018, when the SFMTA sought feedback on its transportation plans for the Bayview, the A. Philip Randolph Institute, a nonprofit organization that advocates for racial equality, told the agency that residents saw the bike lane proposals as targeted at newcomers to the neighborhood.

“Bike lanes make people think of gentrification and they don’t like it,” the institute told SFMTA (opens in new tab).

Despite those concerns, the SFMTA’s 2020 Bayview transportation plan (opens in new tab) did propose nine bike network projects, though the major bike lanes skirted around the edge of the neighborhood. That means that today, bicyclists traveling north-south in the neighborhood either have to face treacherous Third Street or wind their way through side streets that have less traffic but still do not have the protection of a dedicated bike lane.

“You always have to be super aware when you’re a cyclist, but I think even more so when you’re biking in the Bayview, just because there’s fewer safe ways to get around,” said Barbara Tassa, a Bayview resident and cyclist who founded the East Side Bike and Scooter Alliance.

That’s reflected in city crash data, which shows that cyclist injuries in the Bayview have largely stayed steady in recent years, even as crash rates declined dramatically in other neighborhoods.

From 2014 to 2019, the Bayview ranked No. 10 among San Francisco neighborhoods for average annual bicyclist-motor-vehicle injury crashes, totalling 16 per year. Even though the Bayview’s annual crash rate dropped to 14 from 2020 to 2023, its injury ranking climbed to No. 6 as the Western Addition, Mission Bay and Castro all saw larger declines in crashes.

In addition to drawing attention to biking conditions in the Bayview, Bassett’s death has also sparked renewed calls to address doorings citywide.

In an interview after the incident, San Francisco Bicycle Coalition Executive Director Christopher White called for the SFMTA to end its reliance on unprotected bike lanes, which place cyclists between traffic and parked cars, directly in the path of opening doors, and prioritize installing protected lanes.

Given the involvement of a San Francisco Public Utilities Commission employee in Bassett’s dooring, White also wants city agencies to begin teaching a technique called the Dutch Reach (opens in new tab). Using the Dutch Reach, a vehicle driver uses the right hand instead of the left to open the door. This forces the driver to swivel in their seat as they grab the handle, providing a better view of the area behind the car and any cyclists coming up from behind.

Currently, the official California Department of Motor Vehicles driver’s handbook (opens in new tab) does not teach the Dutch Reach. The SFPUC already requires all of its employees to attend a driver safety training that instructs them to open their driver-side door with their right hand and in June, the commission added the “reverse hand reach” instruction to two defensive driving trainings, according to agency spokesperson Nancy Crowley.

Crowley previously told The Standard that the agency was fully cooperating with police investigators, though she declined to share any further information about the worker involved in the incident, citing employee confidentiality. On June 28, an SFPD spokesperson said the incident remained an open investigation, though the department has not responded to more recent requests for updates on the case.

While it is a violation of state law (opens in new tab) to interfere with the movement of traffic by opening a vehicle door, two San Francisco attorneys specializing in bicycle law told The Standard that dooring incidents rarely result in criminal charges. Instead, dooring cases are far more likely to get resolved through civil lawsuits.

Earlier this month, about two dozen people held a vigil for Bassett at the corner of Newhall Street and Fairfax Avenue, where his dooring took place. As a steady stream of cars flowed in and out of the nextdoor Bayview plaza, speakers remembered the 70-year-old Bassett as a passionate Giants fan who loved jazz music and biked virtually everywhere.

“It’s just so tragic,” one speaker said. “I’m hoping we can make our streets safer for everyone.”