Bay Area carpet and flooring company Conklin Bros. (opens in new tab) has existed in one form or another for nearly a century and a half, starting with a mule-drawn wagon and weathering the 1906 earthquake and a constant cycle of economic booms and busts.

An employee for the past 35 years, JoAnn Edson, can’t remember business ever being as slow as it is now.

“We’re struggling,” she said. “We’re just trying to stay open and stay afloat.”

Before Covid, Conklin Bros. bustled with flooring orders for local offices, hotels and hospital systems. Now, the firm has “very few salespeople and very few calls,” she said.

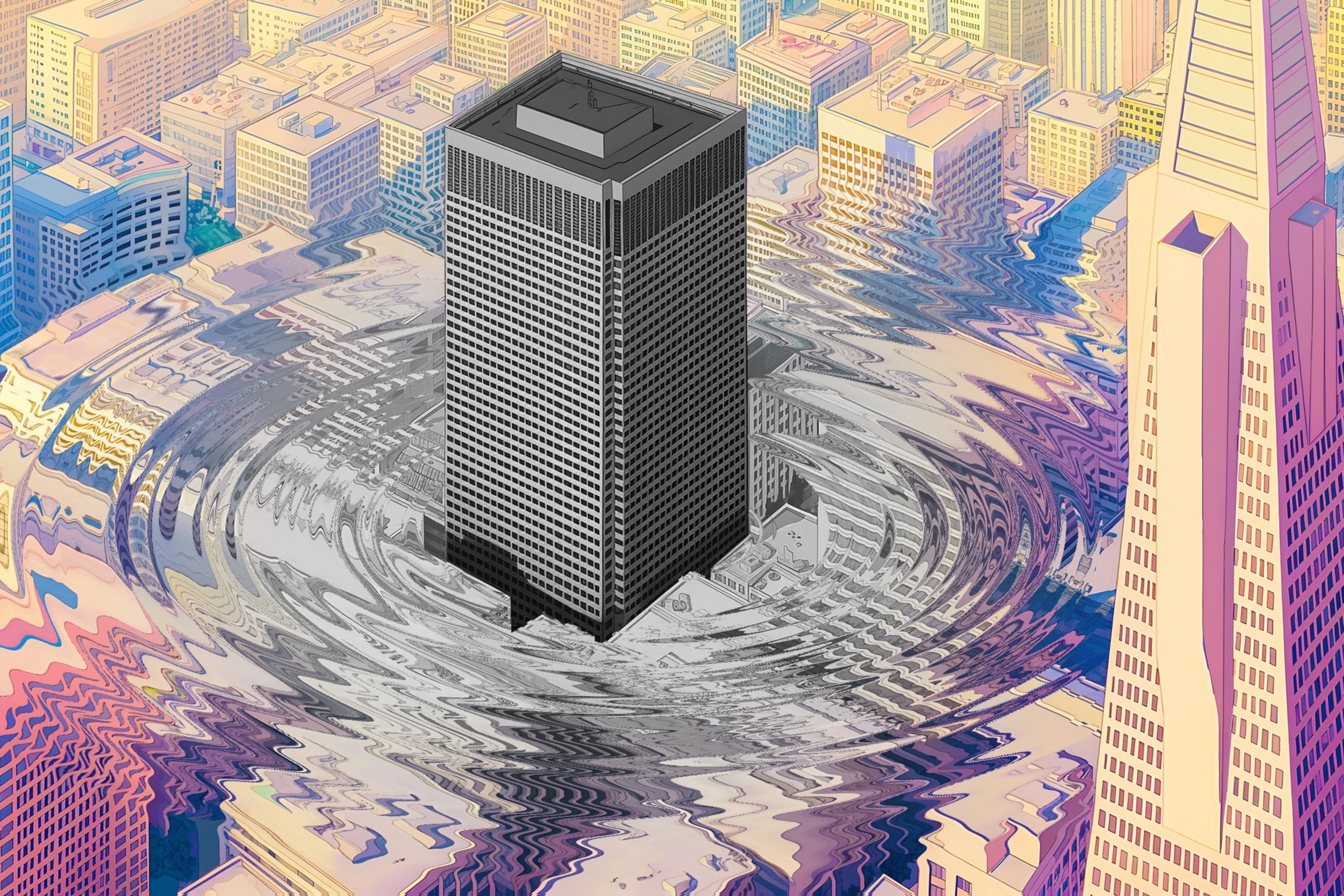

A major culprit is remote work and the growing proportion of empty or nearly empty office buildings that dot downtown. That stagnation — measured in record-high vacancy rates north of 36% — is not just a drag on the city budget but has rippled out like shockwaves, imperiling the once-thriving network of businesses that serve and support office workers.

The situation is improving, elected officials insist, citing return-to-office mandates and the AI boom. But these arguments are little comfort to the companies that are struggling to adapt to what appears to be a permanently changed world (opens in new tab). From furniture installers to plant whisperers, businesses face a choice: wait for an uncertain return to familiar circumstances or pivot to new opportunities.

Warding off ‘desolate’ spaces

Before the pandemic, Indoor Greenery (opens in new tab) had a “99.9% renewal rate,” according to owner Rita Nossardi Stern, as the firm seeded offices with bushy dracaenas or braided-trunk ficus trees.

But the sudden shift to remote work threw that statistic to the wind as companies ditched their offices and had no need for new plants once their contracts ran their course.

“How are we doing? Well, we are persevering,” she said with a sigh. “As an entrepreneur, you need to be able to take adversity and ride with it.”

Christian Figueroa from another plant provider, The Wright Gardener (opens in new tab), echoed Stern. At the start of the pandemic, about half of the company’s staff took voluntary layoffs, as a quarter of its commercial clients dropped off. A handful of employees were “essential workers” who kept plants alive at a time when few people entered office buildings.

Business has since crept back up, though Figueroa has noticed some changes: Fresh flowers on front desks are out (they’re expensive and need frequent replacement), while orchids and moss walls are in (elegant but lower effort).

The few companies utilizing their offices are packing in more greenery, too. Figueroa theorizes that plants offer ready-made vibrancy in an era of lower office attendance.

“We have fewer offices, but the offices that are up and running are actually buying more plants,” he said. “People don’t want to feel like they’re going into a desolate space.”

Among the carrots companies are providing to get employees back into the office are literal carrots — along with sandwiches, soups and tacos, said Sean Li, CEO of CaterCow (opens in new tab), which makes it easier to order food for workers.

After business crashed at the beginning of the pandemic, CaterCow’s bookings in the Bay Area have recovered, though they’re smaller and growing more slowly than in the company’s other markets, like New York and Washington, D.C., where office usage has returned at higher rates (opens in new tab) than in San Francisco.

The Bay Area’s already slow recovery is further impeded by venture capital’s tightened pursestrings, Li added.

“The economic downturn impacts SF disproportionately, because companies in SF are a lot more funded by VC than in other parts of the country,” he said. “Especially at the beginning of the year, we had seen a lot of cuts.”

Redesigning work from work

Jillian Northrup, founder of BWC Architects, (opens in new tab) said she has seen the firm shift toward residential projects as commercial work has withered. Most of its corporate clients are now small companies, while the large players — like Google, which has previously hired BWC to fabricate bespoke office pieces — have stopped calling.

“I’m not surprised, because all I hear about are layoffs,” Northrup said. “It doesn’t really sit well with employees when you lay off a bunch of your staff and then renovate your space.”

Another office designer, One Workplace (opens in new tab), has found a grim niche within the office space apocalypse: helping companies get rid of their furniture and infrastructure so they can move out efficiently. Vice president Dave Bryant used the euphemism “decommissioning space” to explain One Workplace’s cleanup services.

The company’s traditional design business has dipped, so it has also pivoted to providing consulting services and facilitating tech upgrades like higher-quality headsets and better conference room setups, “because that’s what people are looking for right now,” Bryant said.

One type of office furniture actually in higher demand? Phone booths, where workers can take calls in relative privacy, without worrying about distracting chatter or anyone sneaking a look at their screen — in other words, furniture that creates the work-from-home experience at the office.

One provider, Room (opens in new tab), is seeing 50% more customers and units sold than it did in 2019. Payroll services company Gusto, a Room client in SF, recently ordered seven booths to accommodate employees coming in on so-called anchor days.

Before Gusto received the new furniture, there were “literal lines of people waiting for booths or taking calls on the sidewalk or hijacking conference rooms or squatting in the lactation rooms to have some privacy,” said facilities manager JP Espino.

One of the big benefits of furniture like phone booths is that it can be schlepped in and out without major construction.

Bigger build-outs have plummeted in the city, where the value of permitted work for office alterations and repairs sank to $432.9 million in 2023 from a peak of $1.5 billion in 2019, according to the Examiner (opens in new tab).

That has burned construction businesses, heavy equipment providers and installers like Conklin Bros., whose business has slowed to a trickle.

“We’re just sitting here waiting for it to pick up,” Edson said. “I pray to God it does.”