Thirty miles west of San Francisco, along the windswept crags of the Farallon Islands, a plump, slate-gray seabird has found an unusual home: a ceramic nest designed by a renowned Bay Area sculptor.

The nest, one of more than 100 that line Southeast Farallon Island, is the work of Nathan Lynch, a West Marin-based artist and professor who chairs the California College of the Arts ceramics program. Lynch worked with environmental nonprofit Oikonos Ecosystem Knowledge to create the puffy little igloo-shaped nests, each brushed with eggshell-white glaze before being fired at 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit in Lynch’s massive walk-in kiln. Some have divots for air and covers to combat the sun; others look like rigatoni or snail shells in order to mimic the shape of a natural burrow. All are built to last hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

“If you think about the oldest shared pots in the world, they last forever, effectively,” said Lynch (opens in new tab), who has designed and sculpted ceramic nests since 2009. “If, for example, there’s a big wave and they fall in the ocean, they’re not falling in as trash; they’ll just become habitat for another sea creature.”

Lynch has built nests for eight species of seabirds on eight islands, including the Channel Islands and Maui and Oahu in Hawaii. The pods have proved to stay cooler, last longer and look prettier than the wooden boxes researchers have used as human-made bird nests for decades.

Now, with the West Coast buffeted by intense heat waves and El Niño’s ocean warming effects driving seabirds to feed far from their natural habitats, the need for hand-crafted nests is growing. Lynch’s work is soon to expand to Alcatraz Island, where the artist just secured a contract to produce 20 nests that will line the shores.

Ceramic nests in a warming world

Scientists at the Farallones have used wooden nests to study the Cassin’s auklet since 1971. Providing the homes allows scientists to study the behavioral patterns of individual birds, from mating to feeding, and this research has led to policy and management changes. The artificial nests also increase bird habitats increasingly threatened by predation and the effects of climate change.

Originally constructing around 400 nests from plywood, the research team on the island, Point Blue Conservation Science, has been on the hunt for alternatives that can mitigate rising temperatures. According to more than 50 years of data gathered by Point Blue, air and water temperatures off the Northern California coast have spiked to a point that they can kill birds or drive them from their nests, where they are at risk of being eaten by predators.

Though the problem is more acute in Southern California and Hawaii, Bay Area biologists say it takes just one day in the mid to high 60s for heat stroke to kill a seabird.

“On some of these really extremely hot days on the Farallones, in those wooden boxes, those birds were just cooking,” said Meredith Elliott, a scientist for Point Blue. “It’s like a hot car,” echoed Lidia D’Amico, a biologist for the National Park Service who stewards and studies seabirds at Alcatraz.

The birds get so hot in their nest boxes that they are forced to abandon them at midday, said Elliott, “which is not great, because the island is covered with Western gulls that love to eat Cassin’s auklet.”

Scientists have applied a variety of materials to nest building over the last 50 years: cement, concrete, plastic and, now, clay.

In what was likely the first ornithological research article (opens in new tab) co-authored by a sculptor, “Use of Ceramic Nests in a Warming World” concluded in 2023 that clay not only keeps birds cooler through thermoregulation but benefits the environment, since the nests are made of organic material and lack the chemicals found in plywood, such as glue and formaldehyde. Additionally, ceramic nests can withstand being trampled by sea lions and other large animals.

The idea of working with artists to create nests that mitigate the effects of climate change started with Michelle Hester, executive director of Oikonos Ecosystem Knowledge. She was already a fan of Lynch’s work when she approached him to design and fabricate a series of ceramic nests for rhinoceros auklets on Año Nuevo Island.

“We chose ceramics because we wanted to be intentional about materials and design,” she said. “One of the beautiful, esthetically powerful things about ceramics is that it has been around for thousands of years.”

‘Scientists are a lot like artists’

In addition to chairing CCA’s ceramics program, Lynch has shown his work at San Francisco galleries, interior design firms (opens in new tab), artist residencies and museums. When The Standard reached him by phone last week, he was in Long Beach building a life-size ceramic bathtub (opens in new tab).

Playful yet sardonic, Lynch’s work (opens in new tab) ranges from billowing, amorphous blobs to awkward water fountains (opens in new tab), cartoonish podiums and sagging soap boxes. His sculptures and performance art often flirt with functionality and engagement and use absurdity or humor to explore the follies of American exceptionalism, environmentalism and Bay Area politics.

Courses he has taught have included a study of varieties of mud in the San Francisco Bay and how they could be used for ceramics.

“It’s a demonstration of real-world application that’s not pottery and it’s not sculpture,” Lynch said of his unique courses. “My goal as chair of ceramics was to demonstrate as many different avenues of opportunity for [students] as possible. We’re in wetsuits on an island in the Pacific Ocean in a ceramics class, and I feel like that’s pretty good.”

The labor necessary to create the nests, which can take hours for a single model, has led Lynch to seek out a more practical way to produce them at scale.

“There’s more interest from the scientific community than we can keep up with,” he said. “Scientists are a lot like artists in terms of their budgets, and we’re trying to offer something more sustainable than plastic and wood.”

Various approaches have been taken to address the supply issue. In 2010 and 2015, Lynch recruited a class of CCA students to fabricate more than 100 nests for the rhinoceros and Cassin’s auklets at Año Nuevo Island and the Farallones. Last fall, four students in CCA’s business design course proposed finding a small factory in Mexico that could cut costs; Oikonos is exploring this option. But the most promising solution came from Kansas City, Kan., artist Andy Brayman and his studio The Matter Factory (opens in new tab).

“He’s kind of a mad scientist of the ceramics world in terms of how to produce things at scale,” said Lynch. “But he’s still just one guy with an office.”

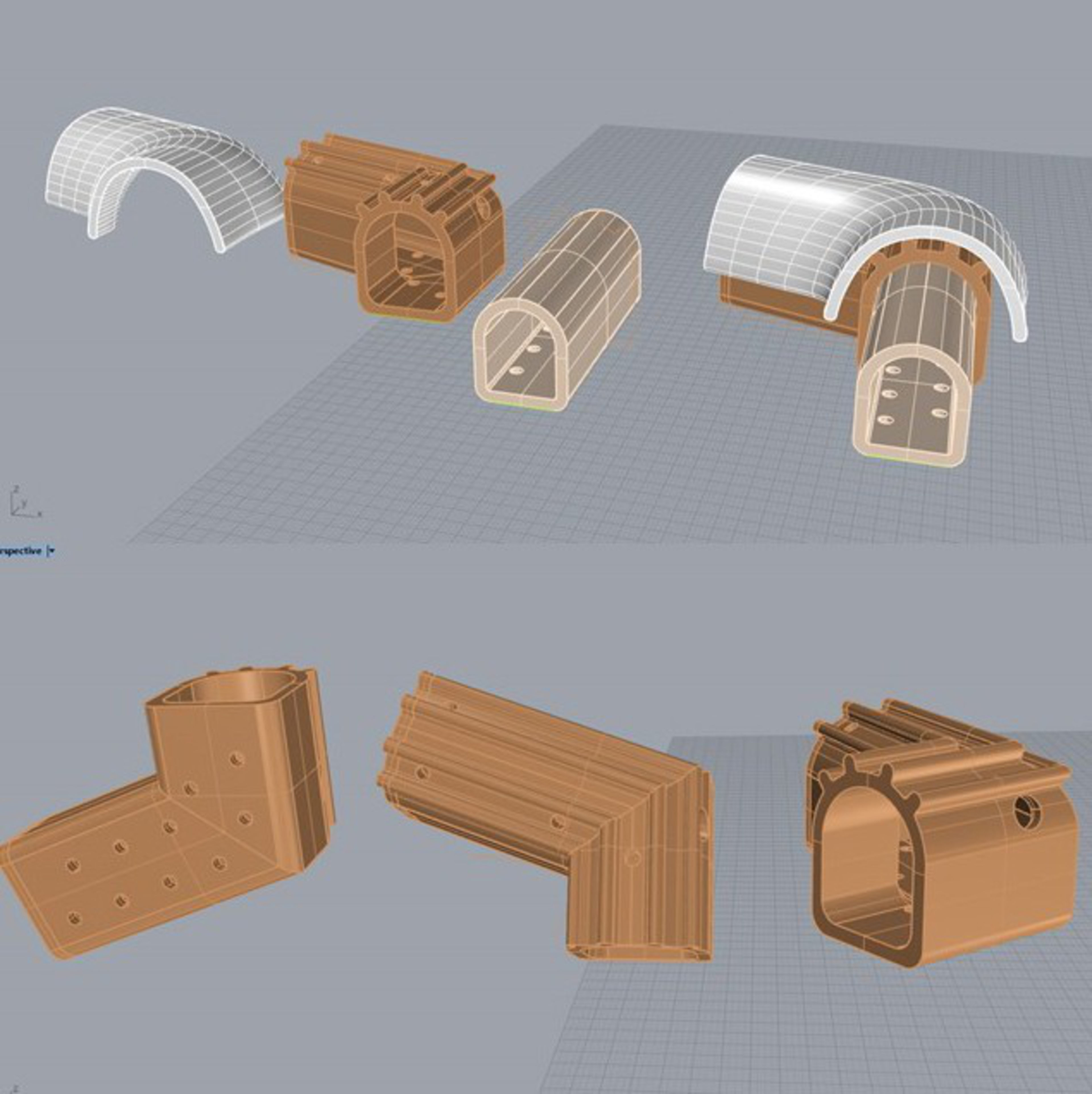

Brayman’s ceramics studio specializes in extruding highly detailed ceramics through large-scale robotics and intensive software. It sounds complicated, but Brayman likens it to a “Play-Doh extruder from childhood.”

“You put clay in, and then you have the profile of the piece that you’re going to extrude, and then you smush clay through it at this incredibly strong process that forms the shape,” he explained.

While Oikonos and Lynch look for the right factory in Mexico to produce their nests, Brayman’s process has become the standard and will be used for the 20 nests to be placed on Alcatraz Island.

A bird bastion re-emerges

Before Alcatraz was home to famous prisoners, including the Birdman (opens in new tab), the island harbored generations of fowl. When Spanish explorer Juan Manuel de Ayala mapped the San Francisco Bay in 1775, he named the island “La Isla de los Alcatraces,” which translates roughly to “Island of the Seabirds.”

Alcatraz was later developed as a military fortress. In the 1850s, the U.S. Army dynamited the perimeter and formed its distinct jagged cliffs, a transformation that prompted a mass exodus of seabirds that would last more than 100 years. When the federal penitentiary closed in 1963, the birds began to return en masse, and today the island is home to more than 5,000 nesting birds. Among them are pigeon guillemots, which were thrilled to find a rich vein of drain pipes and crevices along the perimeter, courtesy of the dynamite from 100 years prior.

In the 1990s, Point Blue arrived at Alcatraz to study the seabirds, introducing the wooden boxes to monitor the pigeon guillemots’ nesting habits as they continue to evolve on an island forever changed by mankind.

Last week, D’Amico secured about $4,700 in funding to start production of the first 10 ceramic nests, which will be installed before March, when the pigeon guillemots make their way back to the island to breed as a part of their annual migration from British Columbia and Alaska.

“The pigeon guillemots will love them,” she said. “They were nesting here long before this island was a cell house or a military base.”

With hundreds of wooden boxes yet to be replaced on islands in California and Hawaii, Lynch and Oikonos continue to search for funds and a larger, more affordable production method for their bespoke ceramic nests. As temperatures rise and wildlife disappears at a rapid clip, the artist and the scientists feel they’re in a race against time.

“There are more seabird clients that are waiting,” said Lynch, “but we just can’t keep up.”