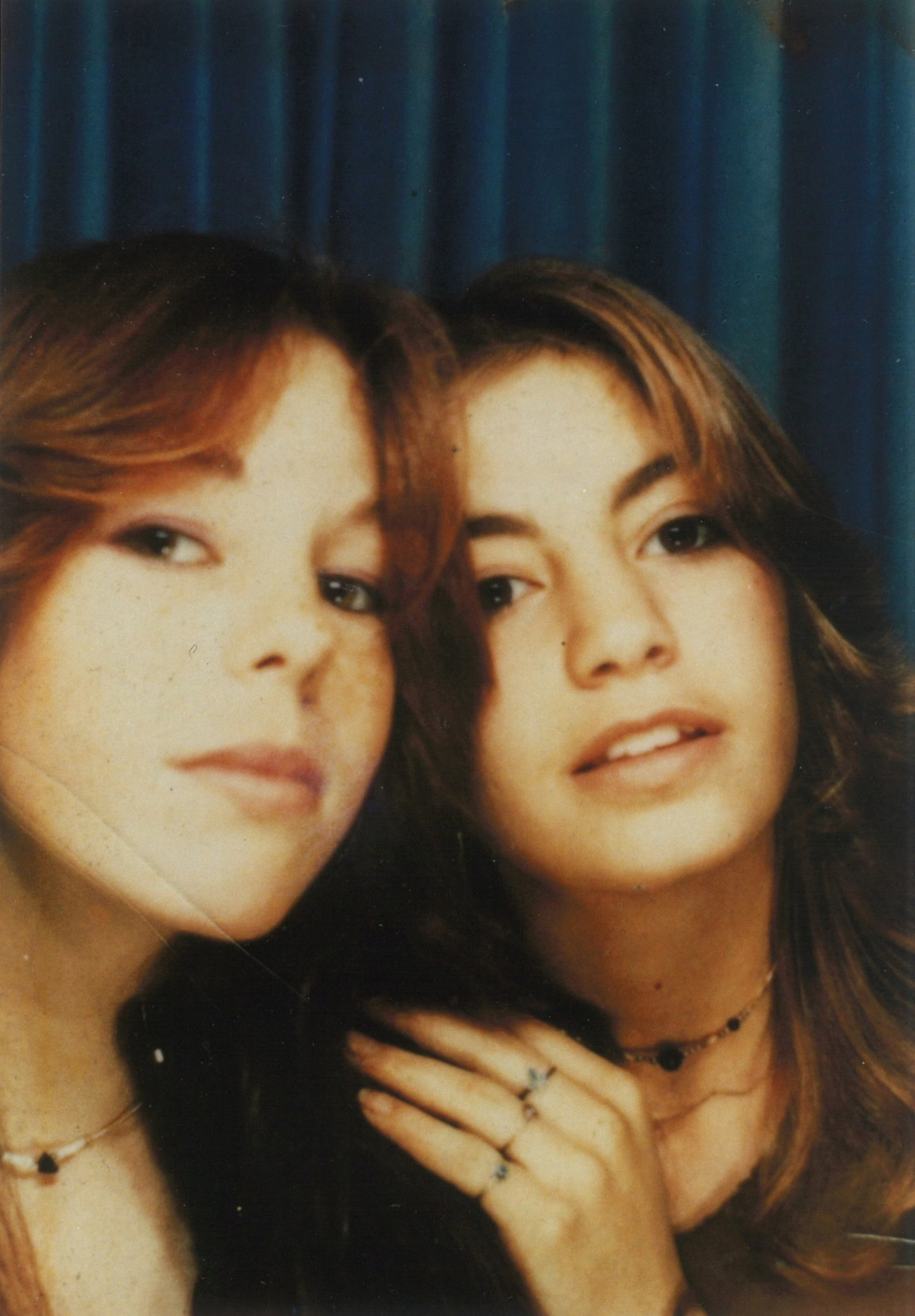

In her first week at Herbert Hoover Middle School, an 11-year-old Rachel Kushner made a friend who asked her to accompany her downtown to help find her sister. The two took the N Judah to Market Street to see the classmate’s sister working as a prostitute.

It was 1979, and Kushner, who had just moved from sleepy Eugene, Ore., hadn’t been in her new Inner Sunset home for two months yet. “I was free because my parents never had any rules,” said Kushner, one of contemporary fiction’s most acclaimed authors. “I learned the bus system very quickly.”

Now a resident of Echo Park in Los Angeles, Kushner, 56, returned to the Inner Sunset last week, taking The Standard on a two-hour walk through her old neighborhood. As she took in the changed scenery, she reflected on the rough and rowdy streets of San Francisco in the 1980s, the Tenderloin as a spiritual locus, and her critically acclaimed (opens in new tab) new novel, “Creation Lake.”

Yet it is her often complicated relationship with San Francisco — like the love for an absent parent — that has shaped much of her work. Her youthful adventures and misadventures in 1980s San Francisco continue to crop up in her novels, even those set far from the cookie-cutter grid of the Sunset, and capture the emotional disillusionment that only an expat can feel.

“It’s hard to explain to people what it was like growing up in San Francisco, and I actually seldom try,” she told me. “It was a fun place to be a teenager but very dark in a lot of ways, and a lot of my friends have a policy of never talking about it because if you mention it to people, they just think you’re making it up, and they don’t believe you.”

I met her on what felt like the city’s first fall day. We had decaf coffee at Art’s Cafe on Irving and 9th Avenue, because 2 p.m. is too late for Kushner to take caffeine — and because Art’s is “one of the places here that’s been here since we moved here,” she reminisced.

As we walked, I heard the real stories behind anecdotes Kushner has immortalized in her books over the years. She told me about the time, at age 12, that she took acid and PCP at Ocean Beach, stopping at the 7-Eleven on 46th and Judah to buy a Butterfinger. “I took a bite of it, and it just turned to sand in my mouth,” she said. “It was the most unpleasant drug experience, and so I just gave it to the character.”

Said character is Romy Hall, the 29-year-old protagonist from Kushner’s 2018 novel “The Mars Room.” Hall narrates portions of the book while serving two life sentences at a California prison, ruminating on her childhood in a brutal San Francisco.

As Kushner spoke of taking off her shoes at Fisherman’s Wharf to beg for money from tourists, I was reminded of her book, “The Hard Crowd: Essays 2000–2020,” a series of vignettes and reflections from her life growing up in San Francisco.

A master of capturing the in-between moments of a person’s life, Kushner’s most visceral scenes come during car and bus rides, in moments of intense contemplation, and when a narrative switches from one character’s perspective to another’s, whether by email or by sewage pipe.

Inspired by a childhood spent transferring on Muni, her ability to breathe life into these small, liminal moments is perhaps most apparent in her fourth and most recent novel, “Creation Lake,” a spy novel and thriller published by Scribner in September, which has been shortlisted for the Booker Prize and longlisted for the National Book Award.

Kushner moved to 8th and Irving when she was a preteen with her parents and older brother, driving down from Oregon in a 1958 Volvo 544. Kushner’s parents were academics, and although they participated in Eugene’s growing but relatively subdued hippie movement, what awaited them in San Francisco was something much larger, darker, and out of control.

“My parents were in this hippie world (opens in new tab), as in they went to parties with people on mushrooms and stuff like that, but not like a kind of Tenderloin-type hard scene,” Kushner said amidst the melting butter and frying eggs of Art’s. “Eugene was extreme townie culture, and everybody was getting into hard drugs. It just sort of seemed like you get into the teenage years and there’s not a whole lot to do besides push boundaries. As it turns out, San Francisco is kind of like that, too.”

“I never lived in a San Francisco that wasn’t always in some conversation with what’s going on in the Tenderloin.”

Author Rachel Kushner

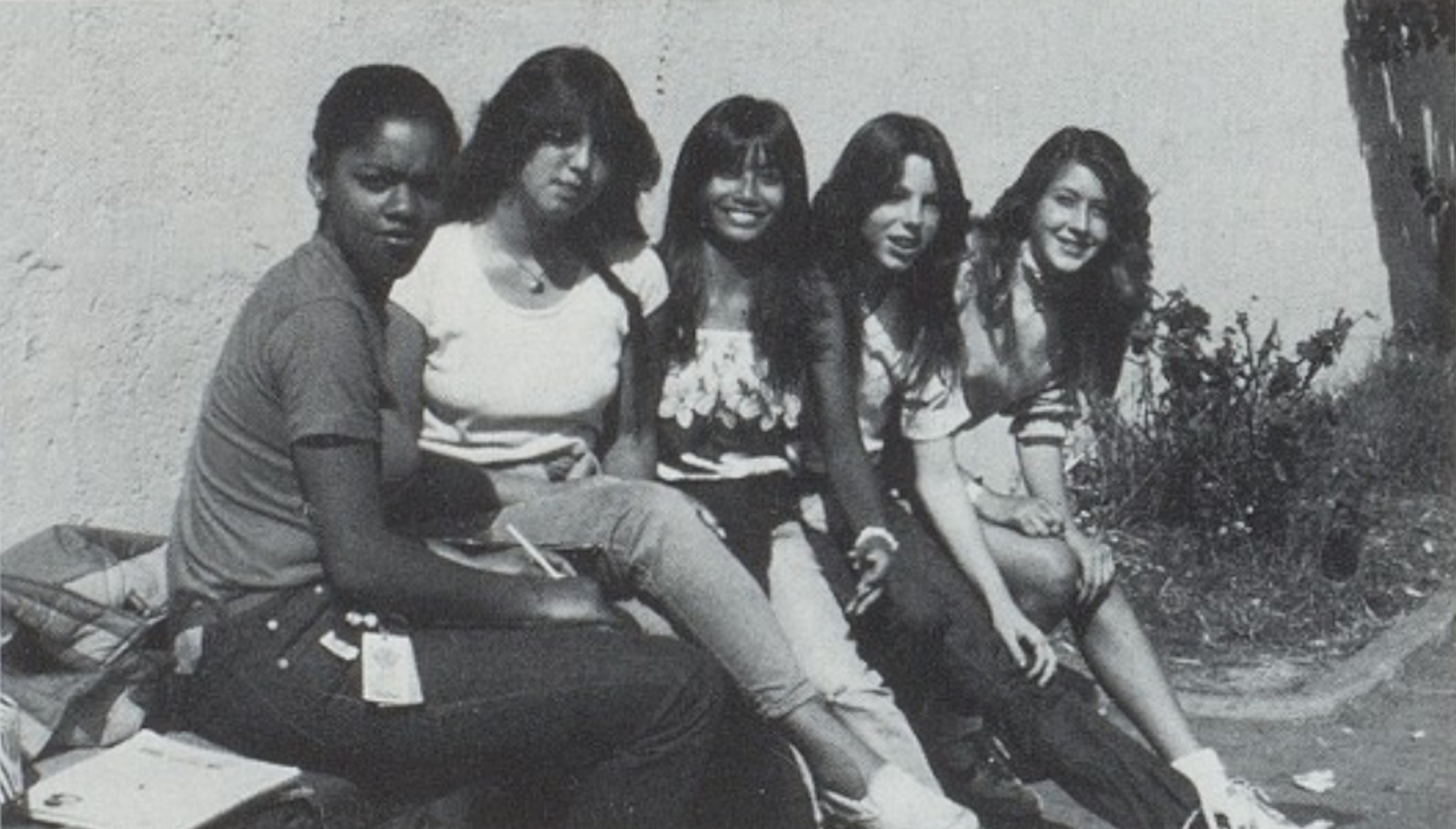

An urban latchkey kid, Kushner was free to explore San Francisco as she wished. At 11 years old, the Muni map was her compass. Her playground was the Civic Center and the Tenderloin. She’d take Muni to the Strand Theater to see movie matinees, sometimes with old men sleeping in the next row over. She played Fascination at arcades with friends who later ended up in single-room occupancy hotels.

“The Tenderloin was shocking, but then I was also almost immediately drawn to it,” she told me. “I never lived in a San Francisco that wasn’t always in some conversation with what’s going on in the Tenderloin.”

In her essay “The Hard Crowd (opens in new tab),” Kushner talks about getting caught stealing jewelry from the Emporium-Capwell on Market Street and having her photo taken by a female police officer with a Polaroid camera.

“As she waved the photo dry, I caught a glimpse and vainly thought that, for once, I looked pretty good. It’s always like that,” Kushner writes. “You get full access to the bad and embarrassing photos, while the flattering one is out of reach. Who knows what happened to the photo, and my whole ‘dossier.’ Banned for life. But the Emporium-Capwell is gone. I have outlived it!”

An Irish neighborhood

In the 1980s, the Inner Sunset was slowly, stubbornly transitioning from a hub for working-class Irish families to an enclave of Asian immigrants. This is, in part, the Sunset Kushner remembers — a stronghold of Irish conservatism, steel-toed boots, and keggers that often devolved into brawls.

“I was from a different milieu, but they were still the luminaries of the neighborhood,” she said of Irish families like the McGoldricks and the O’Boyles, who still inhabit her old memories of the neighborhood. “There’s this long, deep history of sorting things out in a bare-knuckled way,” she continued, as we walked along Irving Street toward her old house on 8th Avenue. “I sort of think you have to be from the Sunset to even understand it, much less criticize it, but I’m still coming to think about the dynamics that made it what it was.”

In Kushner’s memories of her adolescence, most of the homes in the Inner Sunset didn’t have colorful paint jobs, and there was none of the lush foliage that now lines Irving thanks to a city tree-planting grant in 2008. Kushner doesn’t resent these changes or indulge any impulse to nostalgize the way the neighborhood used to be.

“I’m not into that kind of thing,” she said. “The idea that one should give others the impression that the moment has passed and that they themselves participated in the moment — this is a misunderstanding of reality.” Kushner paused to eye up an Edwardian apartment on 8th Avenue where her friend grew up. “This got a lot fancier.”

As we made our way back toward Irving, Kushner stopped to look at a wide-collared 1980s leather jacket that had been discarded on the ground. In blistering red ink, its vintage tag reads “Schott.”

“That’s kind of a cool jacket,” she said, picking it up and wiping the dirt off. “Try it on,” she implored. “It could be a memento from this afternoon.”

I tried it on, and the fit was perfect, as if Kushner has conjured this leather memento straight from the back of a 1980s Haight Street greaser — or from her breakout 2013 novel about motorcycle racers, “The Flamethrowers.”

“You look rad!” she said, and for a moment, as the fog moved over the sun, casting a momentary sepia filter over the neighborhood, it felt like we were in Kushner’s — or maybe Romy Hall’s — Sunset. One filled with “WPODS,” which she tells me stands for “white punks on dope,” a reference to the 1977 song by The Tubes. “It was just barren,” she said of this block back in childhood. “This was the teenage world of 9th and Judah. But my friends said, ‘If you don’t [write about this,] it will never be in a novel.’”

As we stood in front of her childhood apartment and Kushner regaled me with stories of climbing over rooftops to steal trim from a neighbor’s pot plants, a woman watering flowers out front eyed us. It is Kushner’s childhood landlord, Carol.

Shocked, Kushner took her sunglasses off to tell the woman how young she looked and asked if the wisteria in the backyard was still alive.

“It died,” Carol responded. “But we’re trying to replace it with a new one.”

Despite the added foliage, new paint jobs, and disappearance of a handful of Irish bars along Irving, the Sunset has largely been immune to the physical and cultural changes that have permanently altered other neighborhoods.

“Maybe it has to do with the weather or its humbleness, but it has been remarkably preserved. It’s not Pacific Heights,” Kushner says. “I am deeply loyal to the Sunset. My spirit is invested in this place, and I can still locate myself — I am a Sunset girl.”

Having skipped seventh grade, Kushner was accepted into Lowell High School but left after one year for Washington High School, missing her friends. At 16, she enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, to study political economy.

In the end, Kushner spent just six childhood years in San Francisco, and yet, this period informed so much of who she is and what she writes about. Even in the espionage-packed “Creation Lake,” much of which takes place in southern France, there are moments that seem to be imbued with a sense of Kushner’s childhood in the city — stealing for cheap thrills, loathing a landscape the rest of the world insists is beautiful, and characters who don’t play by the rules and look sardonically at those who do.

“It wasn’t very fun being a teenager here,” she said. “It was stressful and there was just a lot of violence. Now, I feel incredibly proud to be from here. It makes me who I am.”