The Keller fire had the potential for a wildland rager-turned-urban-conflagration of the kind that leveled two Los Angeles communities over the last week.

On Oct. 17, a red flag warning blanketed the East Bay hills as wind gusts reached 45 miles per hour and humidity dropped. The Oakland Fire Department pre-positioned teams and engines to react.

The next day, when a spark took hold in a slip of rugged terrain of oily eucalyptus duff and low scrub between dense home developments, the firefighters were ready. They doused the hillside with hoses, and hand crews dug in. By the time it was mopped up, the Keller fire had damaged two homes and scorched 15 acres — a blip in California fire history.

Oakland’s fire chief was blunt: “We dodged a bullet.”

For decades, the Oakland hills held the grim distinction of being the site of the state’s deadliest wildfire. The 1991 Tunnel firestorm killed 25 people, injured 150, and destroyed 3,280 single-family homes and apartment units.

The difference in recent Bay Area fire seasons has been in the planning — but also in the luck.

California’s fire season isn’t truly year-round, but it is increasingly as chaotic as our climate-changed weather patterns. In 2022 and 2023, wet winters knocked back fire seasons in the northern half of the state, while the southern half has remained locked in an escalating drought — and has suffered the resulting firestorms.

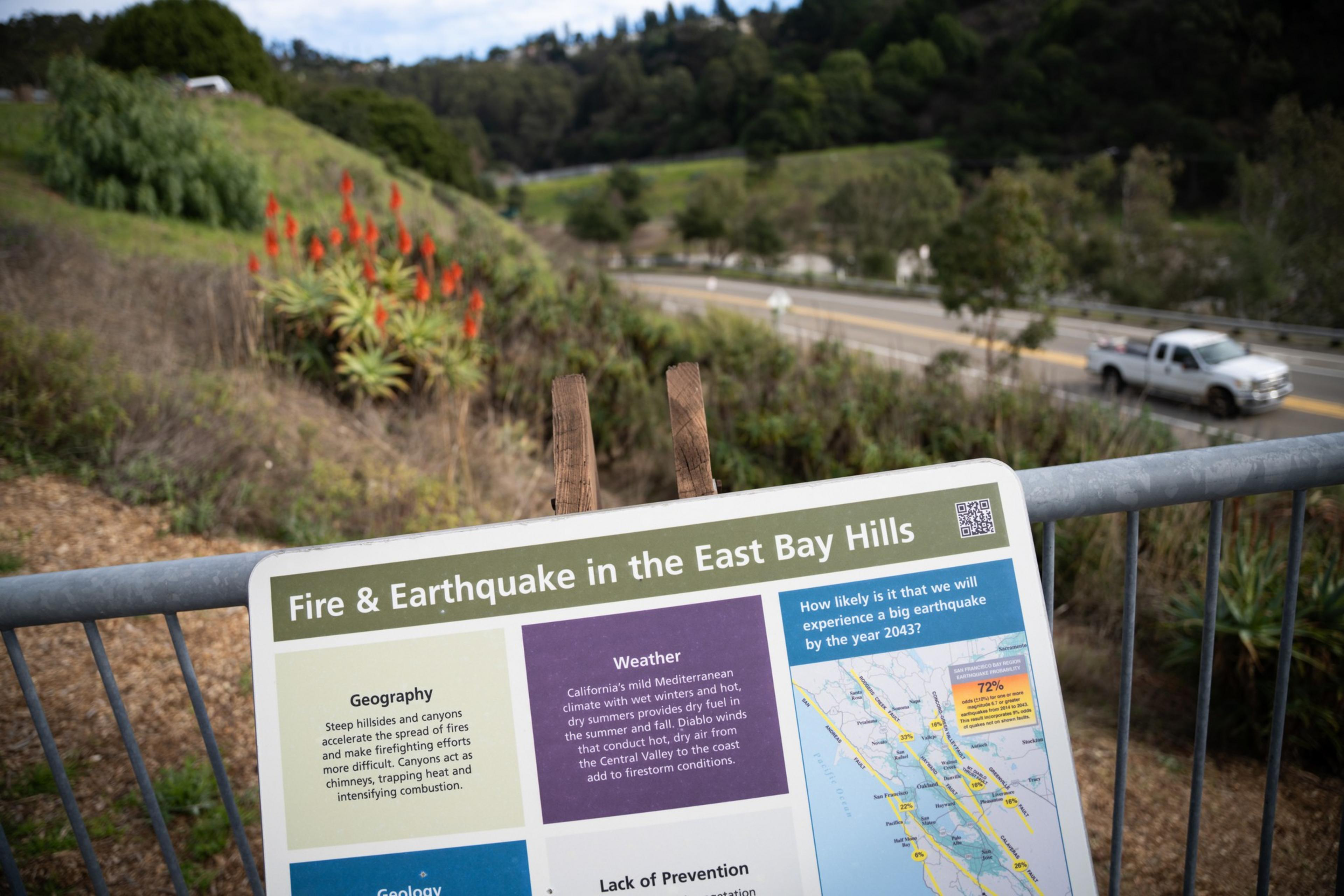

But that precipitation has also filled the hills across the Bay Area with dense new growth, exacerbating decades of mounting fire debt on a landscape that hasn’t burned in years. The Cal Fire hazard map paints a wide red line across the entirety of the East Bay hills, and residents have the insurance nonrenewals to prove it.

As 100-mile-per-hour gusts were flinging embers across the Pacific Palisades and Altadena over the last week, the East Bay experienced its own high winds — but the ensuing snapped power lines failed to ignite hillsides that were green rather than brown. Some day, however, when the wind and the humidity and the spark line up just wrong, our luck will run out. Nature has just bought us a little more time to prepare.

“We could easily be in a situation that L.A. was in earlier this week,” said Michael Wara, director of the climate and energy policy program at Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment and a wildfire policy specialist. “We’ve been there before. We could be there again.”

‘It’s not a wildland fire’

Pyrogeographer Zeke Lunder (opens in new tab) looks at the California fire history map like a psychic with a crystal ball, able to see the past and the future at the same time, in overlapping, transparent Technicolor. Lunder has been performing this mystic science for decades as a fire mapping and land-use specialist.

“What’s striking is, you come in here” — he zoomed over the footprint of the Tunnel fire — “you can’t really tell that happened, right?” Lunder said. “Like, everything’s been rebuilt. But no new roads have been built.”

It was those slim, winding, and dead-end roads that were responsible for at least some of the Tunnel fire’s death toll, as people were trapped in their cars while attempting to escape.

Lunder pulled the view closer to the southern end of the historic fire perimeter, revealing dense blocks of multi-story homes set on steep terrain.

“And then what we see now, like with Palisades, is that when this burns, it’s the houses that are burning house to house,” he said. “It’s not the brush. It’s not a wildland fire.”

From 2017 to 2021, California experienced six of the 10 most destructive wildfires in its history. Those disasters inspired reforms and investments: There are better warning systems, more flame-spotting cameras in the wildlands, and a host of safety-oriented apps. Perhaps most critically, regulators demanded new safety measures from investor-owned power companies that were found guilty of causing deadly fires.

“There are some parts of the code that I think we may have cracked,” Wara said from his home in Mill Valley, with its view of dense woodland hillsides. “I sleep much better at night in PG&E service territory than I did after November of 2017 because of the things the company has done.”

Those include distribution system upgrades and vegetation clearing, an investment of $2.5 billion approved by the California Public Utility Commission, and a policy of public safety power shutoffs in high wind events — tacit admission that the grid as it stands is a firestarter. PG&E shut off power to portions of six Bay Area counties during the October red flag event as the Keller fire burned.

The state spends hundreds of millions of dollars each year on vegetation management, clearing fuel breaks and reducing green, brushy risk for, in the best case, fire containment and, in the worst, safe evacuation. In 2023, more than a million acres were “treated,” but that total doesn’t differentiate between trees near roadsides and communities and those out in the wildland.

The Keller fire was a reminder of that ever-present fuel risk, but also of how far Oakland has come in its disaster response to protect lives as well as homes. The 1991 Tunnel fire in north Oakland was made far worse by a lack of cooperation between municipal and regional response agencies — no one used the same radio channels or the same hydrant hook-ups. Now communications and equipment are standardized, and trained community members even maintain their own radio network.

Doug Mosher, vice chair of the Oakland Firesafe Council, is one of those well-prepared volunteers. “The threat has always been here, but it’s just gotten worse each year,” he said. “Climate change, more people living up here, more vegetation.”

And more flammable types of it. Before the hills were developed by European settlers, they were open oak savannas, grasslands dotted with low-slung trees alongside dense redwood forest stands. After the logging industry extracted those stands, people built homes on the cleared land and planted incendiary and nonnative eucalyptus, juniper, and acacia.

In May, the city approved a vegetation management plan that would cover more than 1,400 acres of property and 300 miles of roadside. And in November, hills residents agreed to a parcel tax that will provide an additional $3 million in funding for that work, along with education, enhanced patrols during red flag events, and annual inspections of 26,000 properties. But Oakland’s budget crisis has set the city back on its heels.

Days before the L.A. fires broke out, Oakland temporarily closed two stations in its high hazard area, including one just south of the Tunnel fire footprint.

“I think closing fire stations is an absolutely reckless plan,” said newly elected City Councilmember and longtime firefighter Zac Unger. “I do not think that is a risk that our city should bear.”

But much of the risk remains beyond the city’s power.

“Wind, dry weather, and lack of rain — these are things that we cannot control,” said Oakland Fire Department public information officer Michael Hunt. “And those factors are really the biggest generator of the devastating events that we’ve seen.”

‘Why did that home burn and this one didn’t?’

A few miles north, architect and Diablo Firesafe Council board president Sheryl Drinkwater sees opportunity in the Berkeley hills. But she also sees danger. “The romanticized image of Berkeley is the shingled house with the wisteria trellis attached,” she said, tightening her scarf against the gusting wind. “And if you’re going to live here, you really shouldn’t have that.”

Drinkwater is one of a small contingent of community wildfire mitigation specialists trained in home hardening, or building retrofits meant to protect structures from fire. When she became a safety assessor for state emergency services, she thought she was preparing for the Big One — as in earthquake. “Then I get deployed in 2017 to Sonoma. That blew me away,” she said. “My thesis statement ever since then has been, why did that home burn and this one didn’t?”

Drinkwater circled the wood-shingled home of Susan Nunes, pointing out its ember-ready retrofits: enclosed eaves; gravel instead of mulch circling the house (“I think it looks nice, not everyone does”); fire-resistant fiberglass mesh designed for utility poles encasing the base of the structure (“she’s a guinea pig for this new product”). Every intervention could stop an ember from taking hold — which is how an estimated 90% of homes burn in wildfires.

As she spoke, Colin Arnold, the Berkeley Fire Department’s wildland urban interface lead, pulled his truck over on the narrow road. He’d just come from a meeting with the City Council about expanding enforcement on the hedges and climbing ivy around 8,000 hills homes. The Fire Department wouldn’t let the L.A. crisis go to waste. “We have an engaged and invested public right now,” he told Drinkwater. “We’ll be really strategic with what’s coming next.”

Berkeley hasn’t seen a significant fire since a 1923 conflagration consumed more than 600 homes north of the UC campus; they were swiftly rebuilt in place. But the city has taken a uniquely proactive approach to potential peril, even recommending (opens in new tab) that residents leave during red flag warnings, before any fire has started, to avoid jamming the hillside hairpins.

In 2022, residents launched Berkeley’s first Firewise community, a neighborhood organization backed by the National Fire Protection Association, with disaster preparation at its core. Since then, nine more have formed.

Positive peer pressure is key to community fire preparedness. In a place where roof shingles may become firebrands, and ivy-covered wood fences can act as fuses, what your neighbors do matters.

Headwater Economics (opens in new tab) estimates that retrofitting a home to withstand embers costs between $2,000 and $15,000. But research after the Camp fire that leveled Paradise in the Sierra Nevada foothills found that one of the greatest indicators of whether a home burned was whether another home burned within 59 feet — a luxury of defensible space that most here simply don’t have. Many of the homes in the Berkeley hills are just a few feet apart.

Preparing for the kind of home-to-home urban conflagration that wiped through much of Altadena and the Pacific Palisades requires more extensive, expensive retrofits that may not be compatible with the aesthetic Berkeley residents prefer. “This is kind of a big balance,” Drinkwater said, gesturing at historic homes that blend into the trees.

But what happens in the hills has ramifications for everyone who lives below them.

She stopped to take in the vista at Greenwood Common, a landmarked enclave of modern bungalows. She looked west as the wind whipped past, across the flats of Berkeley where she lives, down to the water and the crisp San Francisco skyline.

“After seeing what happened in Altadena –” she paused. “That’s rare. But if you think of ember cast, the science says that can be a mile. And it’s only two miles from here to the bay.”