Welcome to The Looker, a column about design and style from San Francisco Standard editor-at-large Erin Feher.

“This house is basically the artist grant I never got,” says Michael Jang of the three-story Edwardian in the Inner Richmond that he snagged in the late 1970s for less than the price of a current midsize sedan.

Jang, 73, is having the biggest moment of his long career. His work is in SFMOMA. A PBS documentary (opens in new tab) about his life and career premieres in May. A garage sale (opens in new tab) of his prints and archives on Friday is expected to be the hottest art party in town. He’s become a bona fide art star.

Yet everything about Jang’s present success feels inexplicably tied to split-second decisions he made 50 years ago: Slipping through the back door of the celeb-mobbed Beverly Hilton with a camera around his neck; snapping hundreds of spontaneous, instinctual shots with his Leica; shoving all his chips into this sliver of San Francisco real estate while fresh out of college.

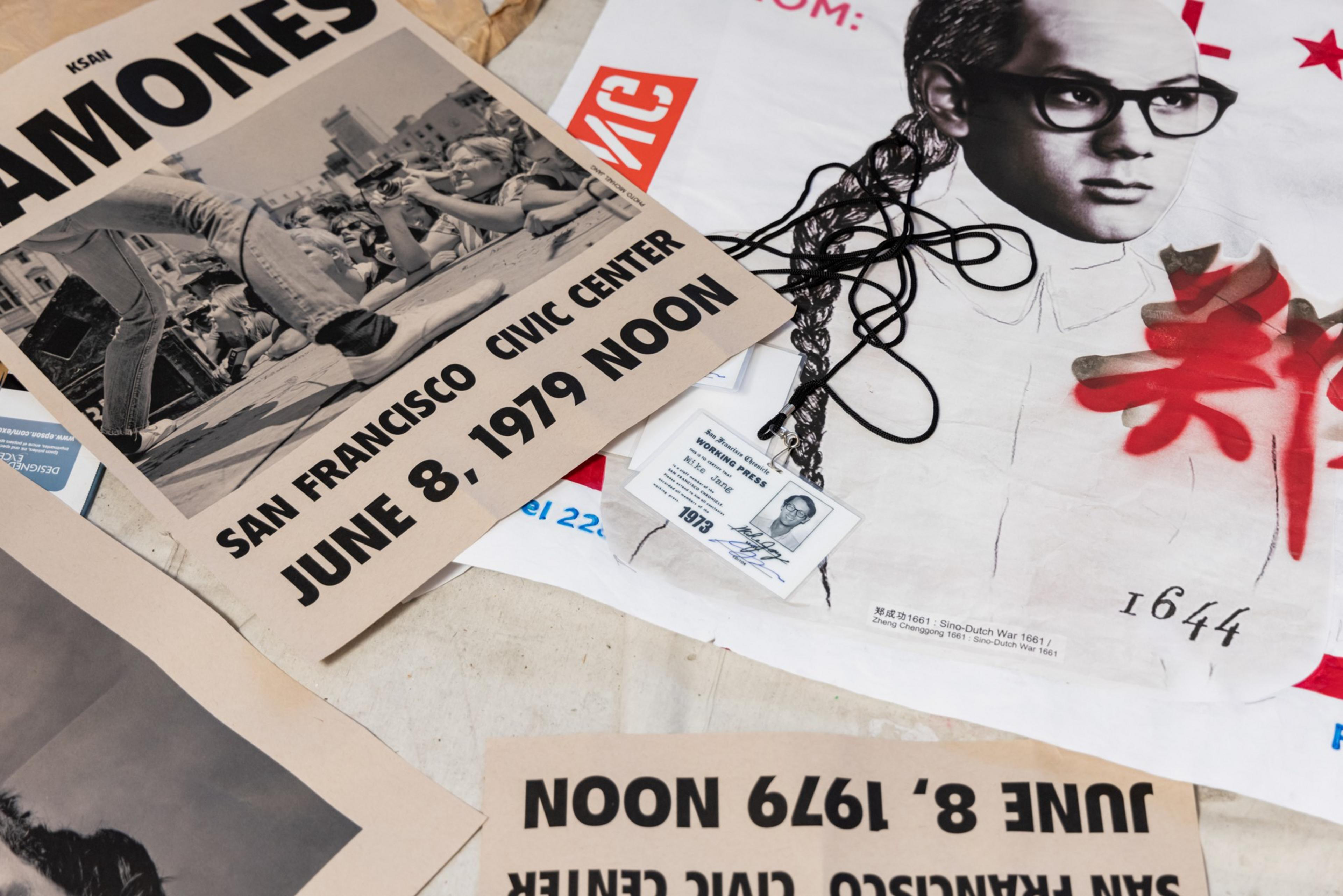

The house has been one of the few constants through nearly five decades of evolution for the artist, functioning as family home, studio, gallery, salon, and archive. Jang raised his two kids here, and before the street-facing double parlor became his studio, it served its typical purpose as a sunny sitting and dining room. Today, its walls are obscured by plywood wheat-pasted with his distinctive black-and-white images. A worktable sits covered with a massive photo collage in progress, freshly sliced paper ringlets hanging off the top and piled on the floor.

Jang spent years studying and practicing fine art photography, graduating with an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1977, but success did not come quickly. He spent most of his working years shooting bar mitzvahs and weddings or taking freelance assignments for local news outlets. His negatives and prints numbered in the thousands and were stored in boxes in the home.

During the Covid lockdowns he started Xeroxing old family photos and pasting them on boarded-up storefronts around San Francisco. For Jang, it was something to do to counter the hostility of the time. As a wave of hate against Asians was spreading across the country, the intimate images of his goofy, smiling, cooking, golfing Chinese American family plastered across the shuttered city stood as a powerful visual response.

People noticed. And took pictures. And posted them. They stalked the city for his next installation like they were searching for buried treasure. Galleries and museums — a few that had never called him back when he was a 20-something hustling for shows with a stack of gelatin prints — began reaching out. SFMOMA commissioned a piece that he had pasted on a boarded-up Goodwill on Geary Street. Jang just kept working, heading out a couple of times a week with a ladder and a brush to paste up new work.

Gallery of 11 photos

the slideshow

“Wouldn’t you rather see the work in the wild than in a zoo?” he asks.

The image-plastered walls throughout Jang’s house have the same impact as his street works. The unexpected juxtaposition of vintage family snapshots and punk-band b-roll images blown to life-size and hastily pasted up gives his 113-year old Edwardian kitchen the same artistic frisson as a shuttered market in Chinatown.

The exterior offers a hint at who resides within: The front door is adorned with a large metal “J,” plucked off the swimming-pool gate from his childhood home in Marysville in Gold Country. Stepping inside, one doesn’t know where to look. To the right is Jang’s studio, an explosion of creative chaos. Straight ahead is an entryway tableau of vintage school lockers against a distressed wall, topped with a sizable fedora collection. To the left is a blood-red stairwell, the walls collaged in Xeroxed copies of Jang’s images and sheets of roughly torn butcher paper, overlaid with stenciled and spray-painted letters, including one of the artist’s calling cards: “Post No Jangs.”

But Jang isn’t the only artist at work here. His longtime partner, the painter and jeweler Alix Blüh, who owns the shop Modern Relics a few blocks away, curated the hallway. Since Blüh moved into the home in 2009, it has become a creative collaboration.

When she first saw the home, Blüh was struck by how Jang had stripped the wallpaper to reveal a glue-streaked look. He’d liked it so much he’d had the walls sealed in their purgatorial state.

“When I first came into this house, and I saw that wall and then the Mark Ryden …” says Blüh, referring to a painting by the pop surrealist in the entryway. “I’m like, oh, I’m in love with this guy. He is just brilliant. I love his taste.”

The feeling was mutual. Jang points out a collection of Blüh’s framed paintings in the bedroom. She handpainted the walls with a mix of stencils and abstract texture. But the subtle, smoky surfaces are a foil to the room’s major moment: Mere feet from the foot of the bed is a wall papered with a 12-by-12-foot portrait of a middle-age Robin Williams, so large that his nose is the same size as the dresser. It’s an iconic shot by Jang, one that for many months adorned the boarded up backside of the Balboa Theater in the Outer Richmond.

“I’m probably the only person in the world that has a massive Robin Williams in her bedroom watching her sleep,” says Blüh.

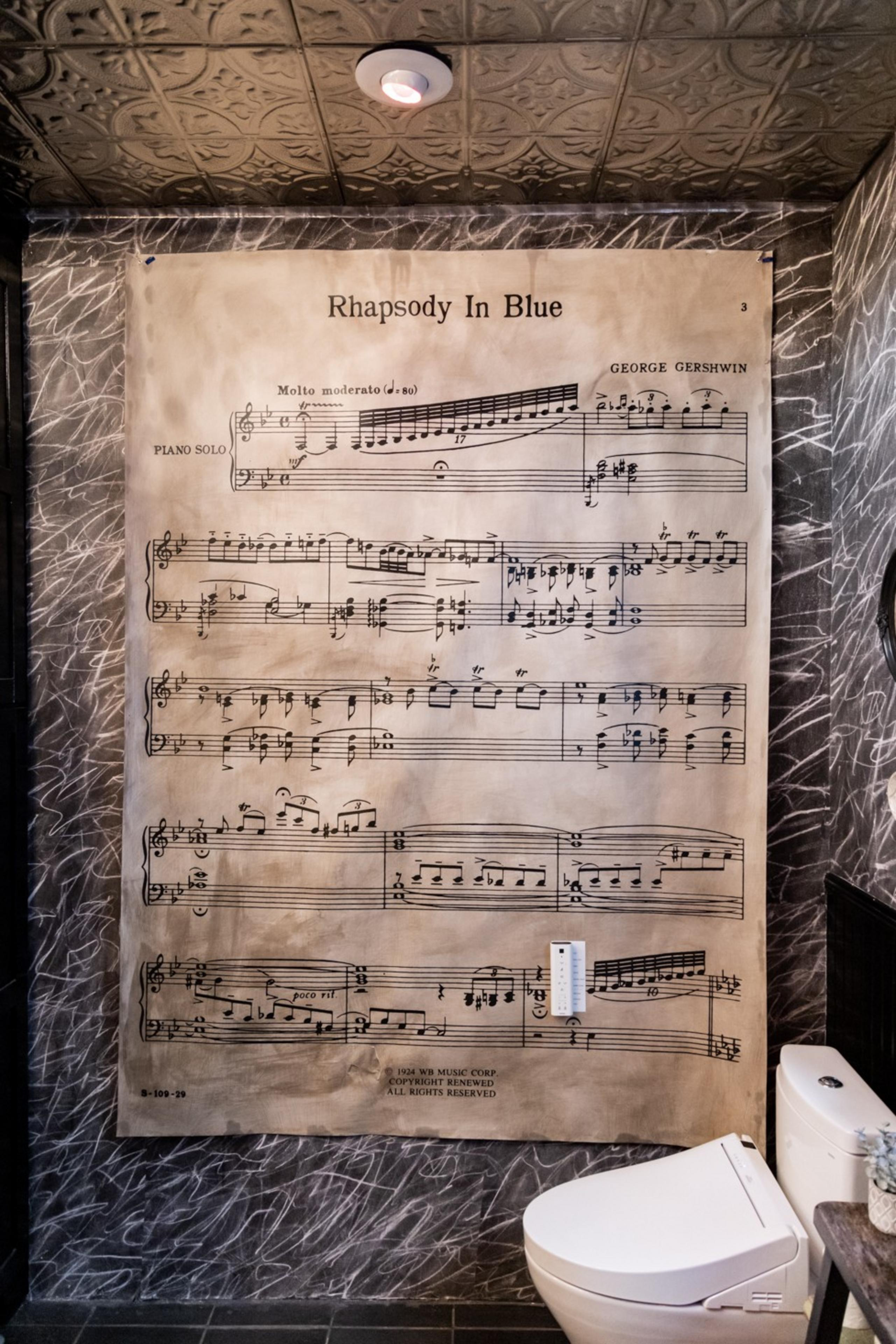

She’s probably also the only one who bathes in front of a giant page of sheet music for George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” and an untitled Cy Twombly painting, reimagined as wallpaper. Twombly’s chalk-like scribbles reach up to meet the pressed tin ceiling, all of it DIY-ed by Jang and Blüh.

“We kind of mushed it there. It’s not perfect, that’s for sure,” Jang says of the “weird epoxy” method he used to install the ceiling. If anyone has perfected imperfection, it’s Jang and Blüh, whose punk-rock ethos remains strong.

In the kitchen, the Ramones are regular dinner guests. Behind the dining table is a colossal black-and-white shot captured by Jang in 1979 when the band played a free outdoor show at the Civic Center. The image is spray-painted over with red serpentine scribbles by artist Barry McGee, who was hanging out at the house a few weeks back.

Pots dangle from a repurposed bike wheel above the stove, and Jang painted his best Basquiat impression on the black kitchen cabinets. The floors, formerly linoleum, are a mottled gray concrete, and Jang’s favorite spot is the cloudy smudge in front of the kitchen sink. “It’s where we stand the most, so it’s all worn down. It took a long time to get there, but now that it did, it’s fabulous.”

The same could be said for Jang’s career.

Nowadays at SFMOMA, his 60-foot mural greets visitors to the blockbuster “Get in the Game: Sports, Art, Culture” exhibition, and last weekend fans waited in a line that snaked throughout the atrium to see the documentary “Who is Michael Jang?” at the museum’s theater. In late December, Jang drew a packed house to American Zoetrope Studios in North Beach when he showed up to sign the edition of the Zoetrope: All-Story magazine he guest designed. And over the past month, archivists from the Smithsonian have been visiting his Richmond home, taking stock. The institution wants to house Jang’s archives.

“It’s kind of a funny feeling,” he says. “Everyone says, ‘Oh, Michael, you deserve it.’ But I’m still the guy who kind of toiled, if not just existed, as an unknown for what felt like forever.”

Last summer Jang rereleased a 7-inch vinyl from the Tymes 5, the 1960s garage band with which he played guitar. Despite the group’s negligible musical skills (“the band is out of tune, the vocals are overblown, the tempo-challenged drums sound like cardboard boxes. It’s great!” went one review (opens in new tab)) the record sold like crazy at the 2024 SF Art Book Fair (opens in new tab). It seems that Jang’s past, repackaged, is exactly what people want right now. At his pop-up “garage sale” (opens in new tab)Friday evening from 6-9pm at Analog Gallery in the Mission, old works of all types will be sold at yard-sale prices.

“There is no great plan. You don’t overthink it. You just work,” says Jang. “You can’t do this with the intention of the museum calling. You just do it for fun. Do it your own way, and just see what happens.”