On the evening of Dec. 1, a man with pure fentanyl in his system and a blood alcohol content almost four times the legal limit suffered a heart attack on the corner of Van Ness Avenue and Market Street, blocks from San Francisco City Hall. He fell to the ground and never got back up.

I know this because that man was my cousin. Out of respect for him and his daughter — a college student and a remarkable young woman — I won’t reveal his full name. He was known to all as Buddy. He may have been on that sidewalk for three minutes or three hours before someone called 911. He had no wallet and no identification, only rings, necklaces, a bottle of artificial tears, and a receipt from a Mexican restaurant. Paramedics performed CPR but, unable to revive him, transported him to CPMC Van Ness. He was later transferred to CPMC Mission Bernal, where he remained for five days, an unresponsive John Doe kept alive on a ventilator.

A CT scan taken at the first hospital revealed “diffuse attenuation of gray-white differentiation suspicious of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy,” or irrecoverable brain damage stemming from a lack of oxygen after a heart attack.

Attempting to identify him, the staff went so far as to translate his Chinese ideogram tattoo: his daughter’s name. Eventually, a staffer from the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner arrived to fingerprint him, and that’s how our family learned what had happened.

Buddy was boyishly handsome, with jug ears and a faint resemblance to a young Mark Hamill. He had an infectious, hiccup-y laugh that made you want to laugh with him.

There are signs that the city’s overdose crisis is beginning to turn around, with preliminary data showing 633 fatalities in 2024, versus 810 the year prior (opens in new tab). But stories like Buddy’s remain common to the point of abstraction. Looking back on my cousin’s years-long decline and how hard the people who cared tried to save him, I think about the countless San Francisco families that have fought on behalf of loved ones gripped by addiction. It’s horrible to watch a talented, successful person succumb to their demons. But even in the darkest days, there may be moments of grace.

A week before Christmas, 15 days after he collapsed in the commercial heart of San Francisco, Buddy died. I was there to hold his hand.

The long decline

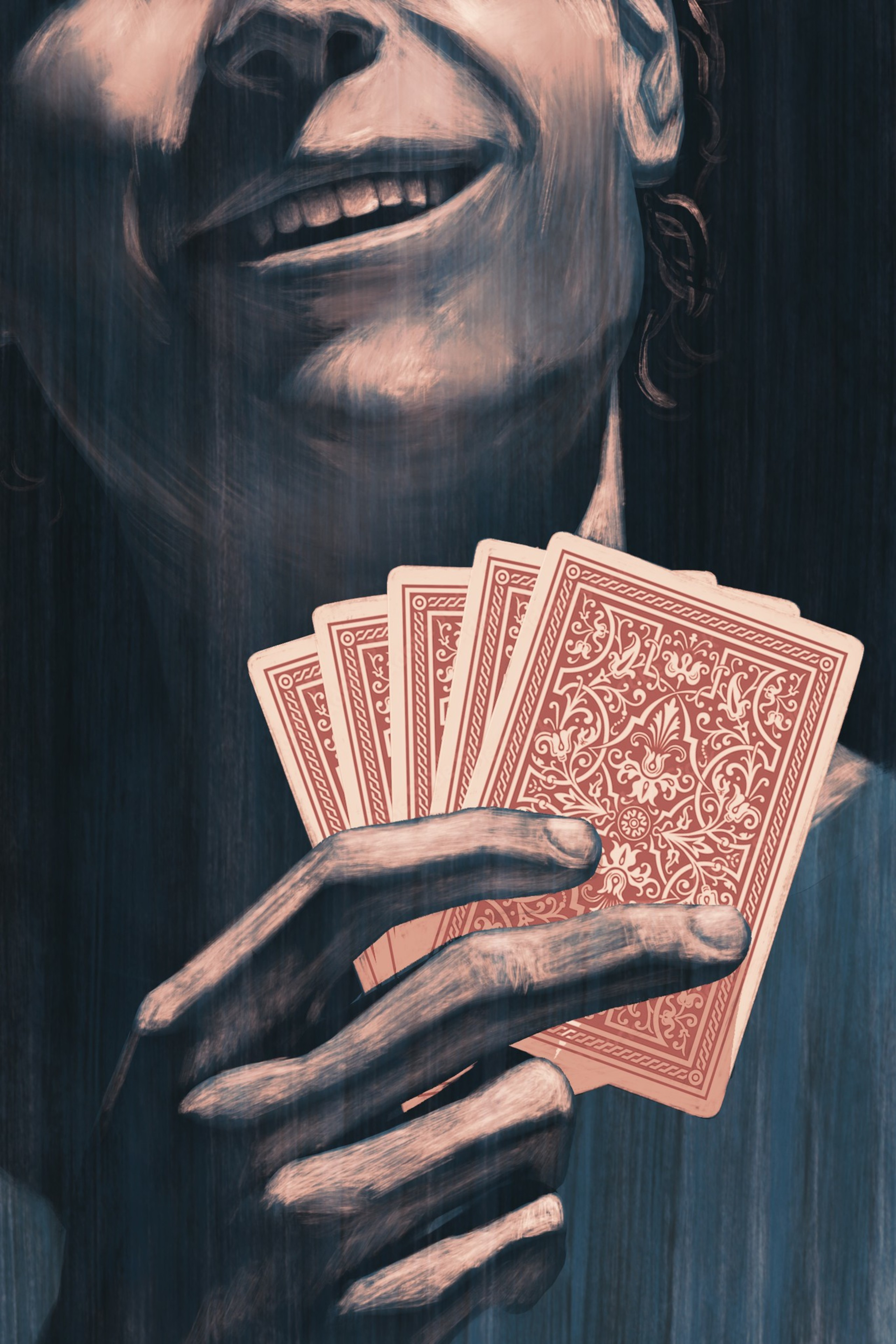

Some of my earliest memories of Buddy involve trying to impress him. He was one of two gay people I knew as a teenager, and the only outspoken atheist. Thirteen years my senior, he was witty and brilliant, although his humor could be caustic. We saw him several times a year because his only sibling, my cousin Barbara, lived with us after their mother died. Buddy was boyishly handsome, with jug ears and a faint resemblance to a young Mark Hamill. He had an infectious, hiccup-y laugh that made you want to laugh with him. Our extended Irish-Catholic clan uses even the most casual get-together as a pretext to drink and play cards all night, and he won every game of hearts.

A programmer, Buddy moved to San Francisco in the early ’90s and did well enough to buy an Edwardian on Noe Street in the Castro. That’s where I stayed when I visited California for the first time at age 19. By the time I moved here seven years later, he’d separated from his partner, and hairline fractures were appearing in his life. Like a bankruptcy, Buddy’s downward trajectory occurred slowly, then all at once. His behavior became erratic during the 2010s, and his programming jobs dried up, so he drove for Uber. Then he lost his car. Rather than list all the struggles, I’ll say only this: It was the meth.

The drug is distressingly common among San Francisco’s gay community. And if you’ve watched someone you love fall into meth psychosis, you know how it goes. If you haven’t, I can tell you that it’s insidious, characterized by paranoia and mood swings. Meth offers a seductive (and false) clarity of vision, insight into a hidden world behind this one. Online communities of meth users persuade themselves they’re victims of “gang-stalking,” (opens in new tab) a vast, 24/7 conspiracy of actors out to destroy them. Try to reason with someone in the grips of this psychosis, and they’re likely to believe you’re a part of it, too.

Buddy’s case was especially frightening. Here was my own flesh and blood, an Ivy League graduate, sledgehammering walls to locate unseen surveillance devices. I did my best to listen to his explanations, but even an innocent question could set him off. In 2020, weeks before the pandemic hit, Barbara and my father flew to San Francisco, and we attempted a family intervention. It went about as badly as it could have. Buddy rejected every offer of help, often explosively.

He lost his job. He lost his home. And he cut me off, along with almost everyone else. At some point, meth opened the door to fentanyl. We knew that, sooner or later, we’d get The Call.

I never heard from Buddy again. After Barbara died of cancer last February, I made a good-faith effort to find him and let him know she was gone. I may have biked past him once in the Tenderloin, but after that, the next time I saw him, he was brain-dead in a hospital. I’m haunted by the way he and his sister came into this world less than a year apart and left it less than a year apart, Irish twins in death as in birth.

The silver lining

It was Buddy’s ex who got The Call. They’d separated almost 20 years before, but the gears of bureaucracy grind slowly. The ex called me and our other cousin, Michael — the third queer member of the family to make a life in the Bay Area — and together, we heard the grim prognosis from a doctor whose tone of voice said it all. No, there was no hope of recovery. Yes, this happens all the time.

But there was a sliver of solace in my cousin’s death: Buddy was a registered organ donor. A representative of Donor Network West (opens in new tab), the foundation that oversees organ donations and transplants in Northern California and Nevada, informed us that, substance use aside, Buddy seemed a strong candidate for successful recovery. Patients on life support are stable, and his body was able to detoxify. Although a prolonged period on a ventilator likely ruled out the use of his lungs, we learned that he had the potential to save several lives and restore sight to the blind. For my family, this news counted as a gift.

It’s horrible to watch a talented, successful person succumb to their demons. But even in the darkest days, there may be moments of grace.

Organ donation is rare. Even among individuals who check the box on their driver’s license and die in a hospital, everything has to go exactly right. Essentially, patients must expire within 90 minutes once the ventilator is removed. Successful organ recovery, we learned, occurs less than 1% of the time (opens in new tab).

Due to medical privacy concerns, I don’t know any recipients’ names, but I was overjoyed to find out that a 43-year-old woman got one of Buddy’s kidneys, a 54-year-old woman got the other, and a 40-year-old man received the liver — all in California. Donor Network West facilitates correspondence between families (opens in new tab), so I extended my best wishes to all three anonymous recipients, and I hope to hear back and learn their stories. I can only imagine what a happy holiday season they must have had.

As expected, the lungs went to medical researchers. Buddy’s eyes, though, were not recovered. As is the case with blood, sexually active gay men are forbidden from donating certain tissues, even if they test negative for HIV and hepatitis C. The seeming caprice of “liver, yes; cornea, no” left me confounded.

I will never uncover the full circumstances of my cousin’s death or be able to piece together his last years, but I learned from the medical team that Buddy had been living in an SRO in the Tenderloin. A few weeks ago, I went there to let the kindhearted staff know he wouldn’t be returning. I found a hospitable environment — threadbare, maybe, but more dorm than prison. No one there seemed to know Buddy well, but I was assured his room was always clean. Walking out, I burst into sobs, crushed that a human life could be summed up in such a politely unmemorable way.

I returned a few weeks later to gather anything that felt sentimental, filling two bankers boxes with T-shirts and tchotchkes. Sitting on a Captain America throw rug and searching in vain for Buddy’s missing wallet, I thought about how he may have been trying to turn his life around, and about all the desperate people who come to San Francisco in search of family members who’ve succumbed to addiction (opens in new tab). Sometimes, they help them in time. Often, they don’t. But all these people have stories, and too often, they remain untold.

Jan. 29 is Buddy’s birthday. He would have turned 57. His suffering is over, and the silver lining for our family is that while he was unable to save himself, he was able to save others. Whoever out there holds a piece of my cousin, I’m so glad you’re alive.