On a cold, windy Saturday in the Castro, models in leather bibs and velvety shorts emerged from MAG Galleries to brave the elements on an improvised runway (the sidewalk). The clothes, from emerging fashion brand J.Ehren, had been made from materials collected from the city’s sometimes filthy streets. It was literally trash. Beautiful trash.

“It’s a direct commentary on consumption and the flaws in our modern existence,” said the line’s 22-year-old founder and designer, Joey Ehrenberg. “It’s a protest against our own destruction, and it’s about taking action to shift our course, one piece of trash at a time.”

Ehrenberg is not alone in protesting the crimes of fast fashion. In the face of high production costs, a cadre of young designers is turning to trash, scrap, and deadstock for inspiration. The fact that this trash fashion originates in San Francisco is not random. It’s a function of local designers’ deep commitment to sustainability and their lack of mainstream fashion cred: When everyone claims (opens in new tab)your city’s style sucks, what do you have to lose?

The J.ehren show, which had to run twice to accommodate high demand, was part of “Garbage Age Fashion and Art,” an exhibition by artist collective Piles of San Francisco (opens in new tab), whose name is a nod to both the plush, looping fibers that stick out of fabric and to heaps of refuse.

“Not having access to the usual materials made upcycling an instinctive choice for me,” said Ehrenberg, who grew up in South Carolina where his father worked at a printing roll company and his mother worked in an eyeglass store. He always had a limited budget for fashion creations. For the showcase, he used discarded upholstery, “ice-dyed” tapestry materials, and scrap leather sourced from city streets by fellow Piles Collective member Liz Cahill.

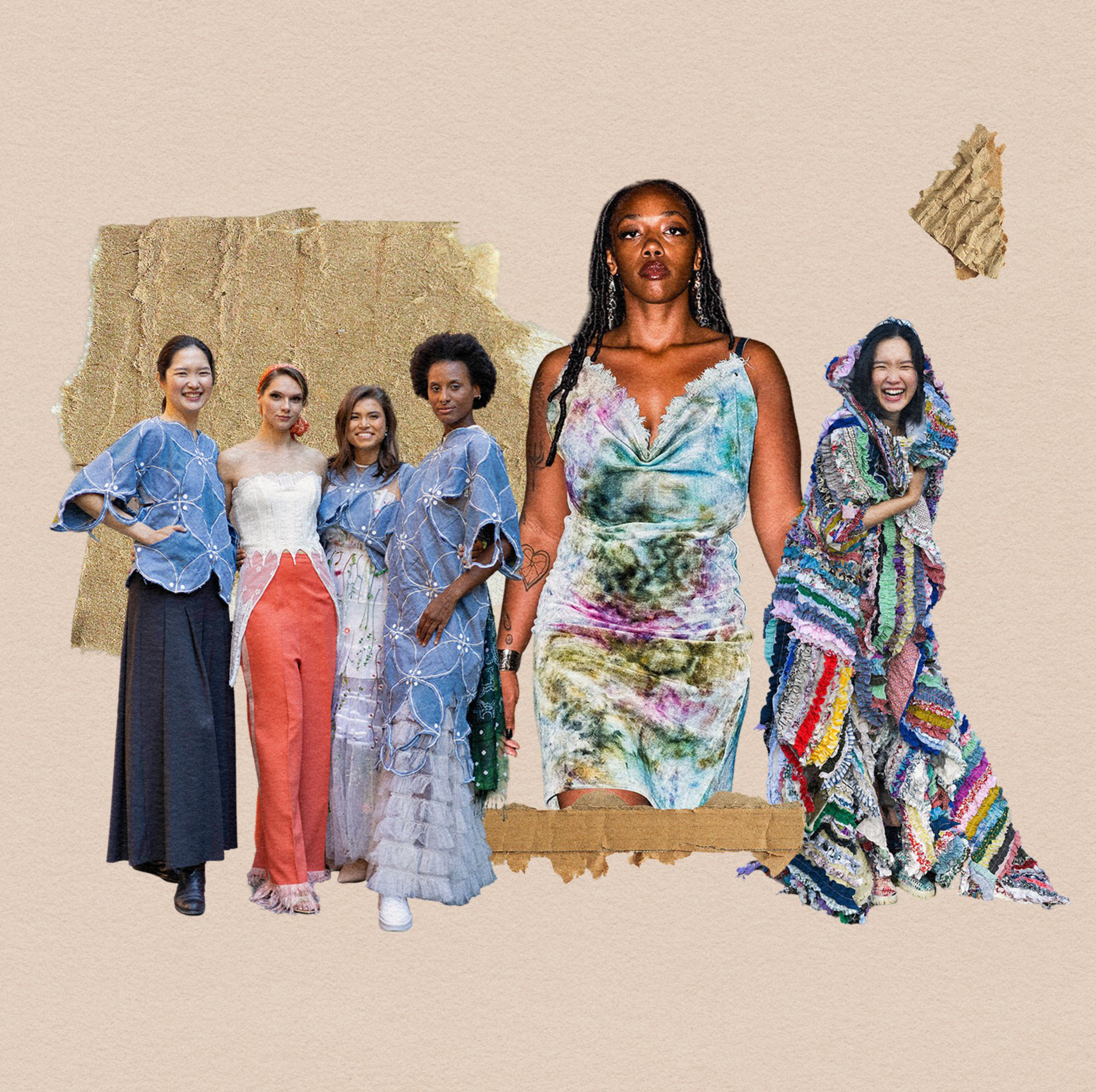

Many other local designers are embracing this scrappiness. The party-forward, sultry label By Vicious (opens in new tab) by community organizer Vile Honey has been putting together trash-forward runway shows (opens in new tab)where emerging designers showcase their work, while Tori Ewald last year launched the upcycled T-shirt brand Delicate Cycle. (opens in new tab)

Capitol Arts, the Mission event space and production studio, held an ethereal fashion show in November for the launch of Neverend, (opens in new tab) a brand selling mesh dresses, “scrunchie” silk bras, and intricate cargo skirts made entirely from scrap and second-hand fabric.

Neverend is the passion project of Haley Slocum, who was working as a senior designer at Levi’s when she began dreaming up her sustainable brand. She wanted the aesthetic to be “high fashion and avant-garde, cool as hell — no crunchy, boxy, unflattering, raw flax crap.”

After leaving the jeans giant in 2024, Slocum began making frequent trips from the city up to Sebastopol to raid The Legacy, a thrift store with “a hot-mess, perpetual-garage-sale vibe.” She stalks estate sales to search for discarded fabric to transform into sexy, see-through dresses, doll-like tops, and on-trend cargo pants.

The decision to source everything second-hand came as much from observing the challenging relationship with sustainability at Levi’s as it did from sheer practicality. “Even when I was working at Levi’s, we constantly saw fabric price increases,” Slocum says.

Indeed, there’s never been a more difficult time to be a San Francisco fashion designer who is not backed by a corporate conglomerate. The cost of raw materials and shipping has been on the rise (opens in new tab) for a few years, while the affordability of housing in the city has been consistently plummeting (opens in new tab). Add general inflation (opens in new tab) to the mix, and you’re looking at a particularly grim collage. “As natural resources dwindle, we will have no choice but to use what we have,” Slocum said.

The same week Slocum debuted her Neverend line, the Ferry Building was taken over by local nonprofit Remake for a sustainable fashion show called Walk Your Values (opens in new tab). It featured the colorful, texturally rich clothes from Gathered Cloths (opens in new tab), an upcycling textile project by Fafafoom Studio, among others. Former fashion blogger and designer Mira Musank is the visionary behind Gathered Cloths, a project she launched in 2021.

At first, Musank used remnant fabric because she was teaching herself to sew and didn’t want to waste expensive materials. But the more she learned, the more she realized there was just no need to buy anything new. According to Musank, there’s an “overabundance” of great textiles, “materials that people held for a long time but didn’t use” and “vintage fabrics and clothes that are still in good condition, or cutoffs from garment factory cutting floors.”

She now pays closer attention to discarded fabric. “I don’t have to look for scraps,” Musank said. “They find me, instead.”

The new guard of trash designers place themselves within the timely conversation (opens in new tab) on the future of fashion, but they also are having more fun than they could anywhere else. San Francisco’s lack of fashion cred means designers here can be more playful and operate outside the glare of critics’ eyes. There can be greater creativity, less commitment to regular collections, and more interactive events blasted all over social media.

San Francisco has long been on the forefront of the low-waste movement, from composting ordinances to used craft supply shop Scrap (opens in new tab) and the textile recycling program from city trash collector Recology (opens in new tab). But as the J.ehren show wrapped with all the models doing one final round, the audience inside the gallery and on the sidewalk cheering, and photography flashes dispelling the street’s darkness, the trash on the runway felt fresh.