Grant Bremer had not even unboxed his belongings at his new apartment — 1600 Clement St., unit 304 — when the power went out for the first time. It would not be the last. It was November, and the apartment’s heat would not turn on. The unit’s internet lines were cut, and the washer and dryer were broken. As the season’s first storm brought heavy rain, a steady stream of water poured out from the dining room and living room ceilings.

He decided he had enough.

Bremer, 31, had been in the apartment just three weeks when he asked his landlords — Sophie Lau, Jeffrey Lau, and their son Kenan — if they would allow him to move out. To buttress his request, he cited city, state, and federal laws governing standards of living and told them that he and his roommate did not feel safe. Bremer offered to pay for the month of December if the Laus would let him break the lease.

The Laus said no. They said he would have to wait until the rain stopped for repairs. Then they issued a warning.

“Don’t forget there are two side to every story,” the Laus said in an email to Bremer that evening. “If you want to bad mouth us, we will surely return the favor, write up how unreasonable & difficult tenant you are.”

Bremer chose to move out. Sophie Lau said that because Bremer did not pay January’s rent, she kept his security deposit as collateral. When asked if she would pursue legal action, she scoffed.

“If I took to court every tenant who owed me money, I would have tons of cases,” she said.

Indeed, she does. From 1986 until 2023, the Laus racked up more than 100 lawsuits. In as many as 60 instances, the Laus have sued tenants for allegedly breaking leases, withholding rent, or damaging the apartment. They have also filed many lawsuits against contractors, and in at least two cases, lawyers have sued them for alleged failure to pay attorney fees.

Across their 10 properties, 460 complaints have been made to the Department of Building Inspection claiming leaking ceilings and windows, broken appliances and plumbing, mold, lack of heat, and other grievances. Despite the lawsuits and complaints to numerous politicians and city departments — DBI, the Rent Board, and the city attorney’s office — the Laus continue to rent to tenants allegedly substandard housing.

An investigation reveals that the real estate mini-moguls have been operating alleged shoddy apartments for decades, becoming among the most controversial landlords in San Francisco.

A real estate empress

Standing just over 4 feet tall, Sophie Lau, 82, arrived in the U.S. from Taiwan in 1960. After graduating from City College, she owned a fashion boutique and later ran a Chinese restaurant before investing her small fortune in real estate. She was a founding member of the Chinese Real Estate Association of America, meant to empower brokers in San Francisco in the 1960s and ’70s.

Over the last half-century, the Laus have amassed an impressive portfolio of residential and commercial properties across the city worth at least $6 million, according to property records.

The family’s 10 buildings and 70 units span the Inner Richmond, Nob Hill, North Beach, Presidio Heights, Ingleside, and West Portal, where they live in a large home on Sloat Boulevard punctuated by twin stone lions and a stately fountain. They also own a spacious ranch home in Novato, a house in Sacramento County’s Elk Grove, and an entire city block in downtown Las Vegas.

“Is she still alive?” Vicki Ozuna, a Vegas code enforcer, said with a laugh when The Standard asked about Lau. Ozuna called the family the most problematic property owners she has dealt with during her nearly 30-year career.

The Laus spent millions during the 1990s and 2000s acquiring the properties on the edge of Las Vegas’ storied Fremont Street. Marred with graffiti, containing asbestos, and saddled with alleged code violations, an abandoned hotel on the lot attracted squatters and numerous fires that were alleged to have sent homeless denizens hurling from windows (opens in new tab).

City Manager Scott Adams declared the property an imminent hazard — only the second time in two decades Las Vegas had made such a declaration — and ordered its demolition at the Laus’ expense, along with $100,000 in liens and penalties.

Before the hotel could be demolished, Timothy Elson, an attorney who represented the Laus in their dealings with the city, sued the family’s real estate company, claiming $700 for what he said was nonpayment of legal fees.

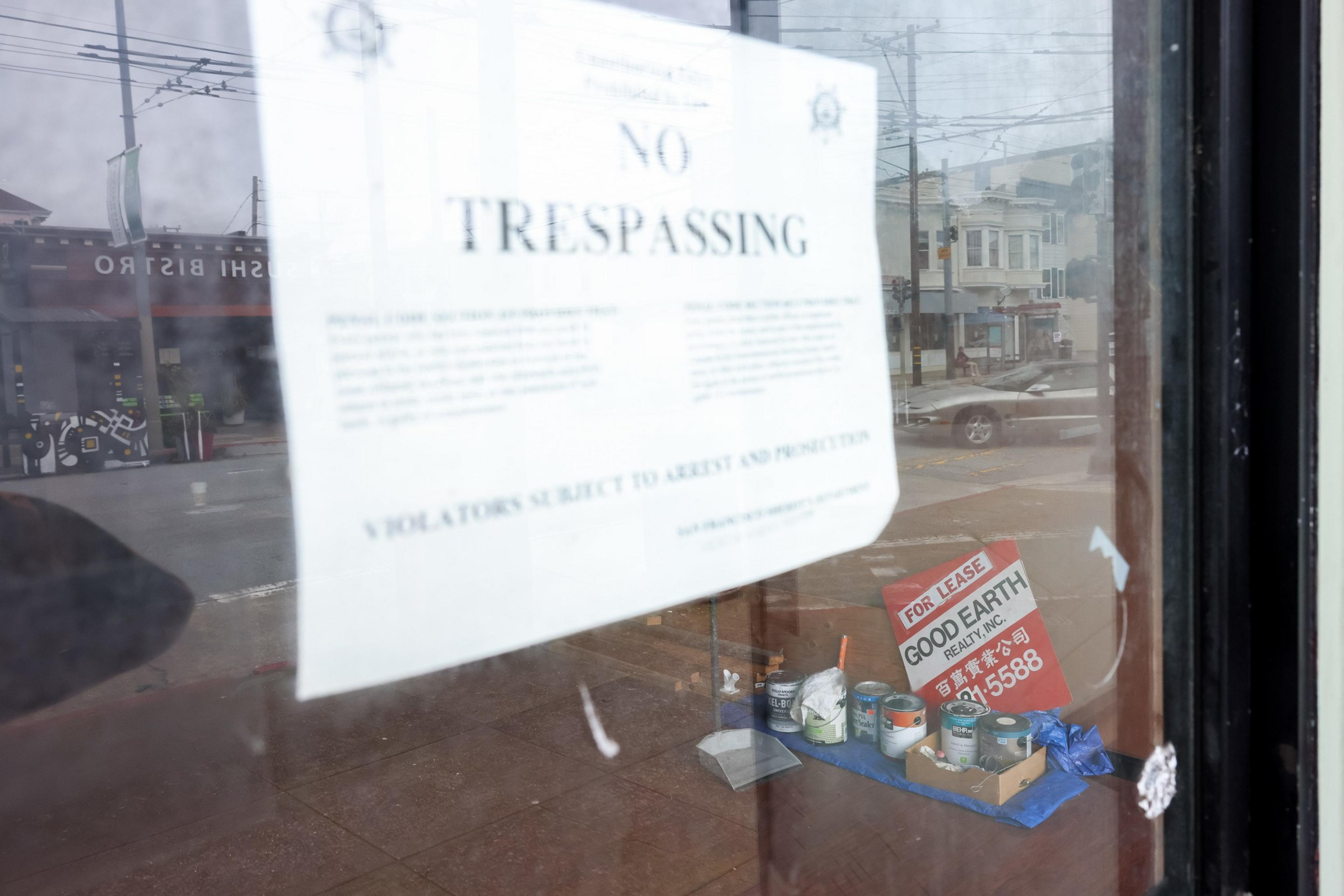

In San Francisco, several of the Laus’ properties are now vacant, including a four-unit strip mall in the Richmond and the company’s office building in North Beach. The former offices sit on a prominent corner of Columbus Avenue and earned the Laus international news coverage (opens in new tab) in 2016 after they raised tenant Neil Hutchinson’s rent from $1,800 to $8,000. Despite help from former Supervisor Aaron Peskin, Hutchinson was evicted.

“Haven’t heard that name in a while but she’s definitely the definition of an evil landlord!” Peskin asserted in a text message when asked about the Laus.

Hutchinson, who moved into an abandoned warehouse in Islais Creek after being evicted, said his experience with the Laus was traumatic. After three lawsuits, the Laus were forced to pay him $49,000.

Sophie Lau said she didn’t remember being involved in litigation with Hutchinson — or paying him nearly $50,000 — but stood by her decision to raise the rent, saying he had taken advantage of low rents for far too long.

“Why should we let him continue to pay $1,800?” Lau said. “We have to do everything the law allows. The guy never had an increase, been there for ages, paying $1,800 — people have no moral[s]. They just think day and night how to take advantage of the landlord.”

The sentiment echoes a statement Lau gave the San Francisco Chronicle in 1980 for a story about rent hikes in North Beach: “This is not a Communist country where they can say you can only charge so much.”

The Columbus property is now derelict. Mold festers across the walls through broken plastic shutters. The family business’s name,“Good Earth Realty Inc.” is visible in tarnished gold letters above the ground floor.

Just a few storefronts away is the Italian Homemade Company, a restaurant that has operated out of a Lau-owned property since 2014. When it comes to fixing infrastructure, “we’re on our own,” said owner Mattia Cosmi.

“The roof needs to be completely redone, and what we get instead is a bunch of patches here and there, and we still have water leaking problems,” said Cosmi. “They don’t spend one penny on their building even though we’ve had water leaks and many structural issues. We always have to fix them by ourselves.”

In a 2018 report conducted by three North Beach community groups on the neighborhood’s “vacancy crisis,” it was found that Sophie Lau and one other landlord owned 20% of the vacancies.

The drip never stops

At first glance, unit 304 is not too shabby. For $3,600 a month, the two-bedroom, 1,000-square-foot apartment has a view of Park Presidio, hardwood floors, and a charming tiled bathroom. On a sunny, warm day, living there is a treat — so long as the appliances and power are working.

Keith Hawkins has done construction work at 1600 Clement for two years. He said he gets hired after every rainstorm with specific instructions to use short-term remedies on leaks that have plagued the building for decades.

“It’s a nightmare,” said Hawkins. “We’ve done so much caulking and patching, but the whole building needs a big overhaul. It’s like putting a Band-Aid on a huge cut. They get people’s money upfront, don’t tell them about the leak, then people get frustrated and move right back out.”

Such was the case for Jenna Giusto, 28, who moved into Unit 304 in January 2023, nearly two years before Bremer.

Like Bremer, she lacked heat and caught the water dripping from the living and dining room ceilings in saucepans; webs of black mold covered the west-facing wall. She shivered at night while suffering from daily migraines stemming from long Covid. Her roommate developed a wet, guttural cough that would not subside.

Tenants commonly complain that the landlords refuse to turn on the heat, even well into the winter. The landlords sometimes respond to the demands by accusing tenants of having issues with their body temperature or being malcontents.

In a phone interview, Sophie Lau said she keeps the heat low because tenants are more likely to complain about it being too high. No evidence of tenants complaining about excess heat was uncovered during The Standard’s investigation, and Lau did not provide any when asked.

“Everybody has a different body temperature,” she said. “I mean, if it’s below the standard, don’t you think we would get a citation?”

The Laus have been issued multiple violations from DBI and the Rent Board over lack of heat from the building’s central heating and hot water systems.

After several emails about water leaking into Giusto’s apartment, Sophie Lau visited unit 304 to inspect the damage. Her assessment was that, despite evidence of water damage and video documenting the leaks, there was no leak.

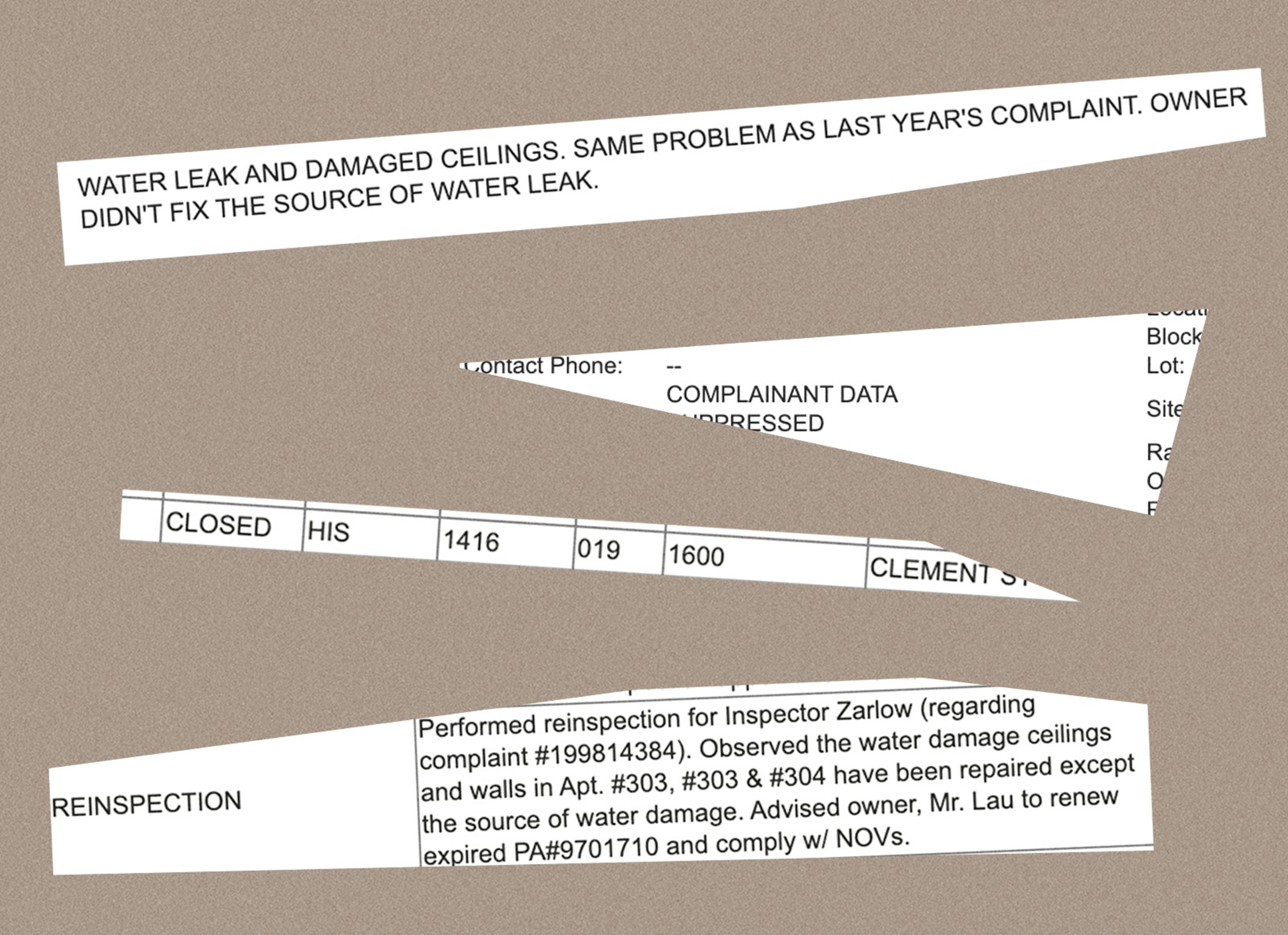

The unit has had documented issues of water leakage for decades. The earliest complaints from DBI date back to 1999, stating:

“WATER LEAK AND DAMAGED CEILINGS. SAME PROBLEM AS LAST YEAR’S COMPLAINT. OWNER DIDN’T FIX THE SOURCE OF WATER LEAK.”

The Standard spoke with three other tenants from 1600 Clement who said they experienced water leaking inside their apartment in the last year. Vincent Lopes, who lives in unit 204, directly below where Giusto and Bremer lived, said he gathered three quarts of rainwater in 10 hours from a rainstorm in late February.

“Me and my wife are just trying to get the fuck out of here,” said Lopes. “The Laus — they are slumlords.”

A pattern of neglect?

During her three months in Unit 304, Giusto filed two complaints about the landlord and the unit. Three months later, DBI closed the case, citing only a violation for lack of heat because the water leakage was not visible upon inspection.

“We only cite what we see,” Patrick Hannan, a spokesman for DBI, said in an email.

DBI closed Bremer’s complaint — which claimed leaks, inoperable laundry machines, lack of cold water, and internet problems — within two weeks, stating that inspectors were unable to access the unit.

The cases of Giusto and Bremer highlight concerns about DBI’s handling of tenant complaints and whether inspections effectively address habitability issues. With problems persisting despite official reports, tenants are left to question whether the system meant to protect them is working.

After submitting his first complaint to DBI, Bremer was shocked to find that there had been more than 100 complaints about 1600 Clement over the past few decades.

“I thought, ‘Oh, fuck — this place has insane amounts of complaints,’” Bremer said.

The most recent complaint was lodged Feb. 26, 2025, citing “at least 10 lineal feet of bowing brick,” a structural issue most commonly associated with water damage.

The Laus are a mainstay in the city’s Rent Board database, which tracks and mediates landlord-tenant disputes. Christina Varner, deputy director of the Rent Board, said the Laus have repeatedly lost petitions to lower rents due to poor housing conditions. Varner added, however, that the Laus have been absent from the rent board petition system for a couple of years.

Sophie Lau often employs tactics to hamper her tenants’ ability to complain or move out without shelling out thousands of dollars. She routinely skips DBI hearings, hires other property owners or her son to do her bidding, files counter lawsuits, or imposes costly lease-breaking penalties like the one Bremer faced.

Several tenants of the Laus declined to speak with The Standard.

“If you make a direct frontal attack and go to the Rent Board, they become more resistant, resentful, and reluctant to do anything,” said a tenant in his early 50s who has lived at a Lau property for most of his life and spoke on the condition of anonymity. “I’ve been fighting this battle for a while, and I’ve learned how to get things done with the Laus.”

Because he is disabled and no longer works, the tenant cannot afford to move his family out. He has become an expert tinkerer over the last two decades, fixing his own — and even Giusto’s — appliances from time to time.

“It’s evil, but it’s genius in a way,” said Giusto. “The fact that they’re getting around all this is crazy to me. I don’t understand how they can live their lives like this as such evil people. Truly. Deeply. Evil.”

Giusto and her roommate left the apartment in early January, while their six-month lease was still active, before deciding to break it early. Giusto, like Bremer, was denied an easy exit from unit 304. The Laus attempted to keep her $5,000 deposit, accusing her of breaking and stealing two of the apartment’s venetian blinds.

“It was unlivable, and we weren’t even living there for a month by the time the inspector came,” Giusto said. “[As if] I’m going to take your shitty blinds.”

Theft of blinds is a recurring accusation by the Laus, according to reviews on Yelp (opens in new tab).

Parrying the Laus’ accusations, Giusto compiled a 17-page list of problems that came with the apartment and a strongly worded letter from her lawyer. After being threatened with litigation, the Laus returned her deposit.

Sophie Lau denies any fault on her part and called nearly every claim detailed in this report bogus. She said landlords are “second-class citizens” in San Francisco.

“It’s well known [if you] have a bad tenant it’s like a nightmare & can cause [a] landlord’s life [to be] miserable,” she wrote in an email. “There is no fairness & justice, can you feel our pain & frustrations, if you are in our position what can you do?”

The Standard visited 1600 Clement in early February to determine if there were new tenants at unit 304. The building’s gate and front door, which tenants say have long had locking issues, were jammed and could not close all the way.

Unit 304 was empty, its door ajar, and where saucepans once sat to collect rainwater, there was a blue inflatable pool, water dripping onto its plastic bottom from the ceiling.