Chrissy McGarry remembers the night at South by Southwest as the flash of lightning before the storm.

It was March 2023, and McGarry, COO of the defense tech startup Second Front Systems, had gone to a bar with colleagues, including Tyler Sweatt, then the company’s chief revenue officer. Sweatt, coming off a stressful month of negotiating government contracts, snapped at McGarry in front of their coworkers. “It was so abrupt and abrasive,” she remembered.

She teared up on the ride back and later confronted Sweatt at their Austin, Texas, hotel, questioning why he had undermined her in such a public way. He reminded her of their shared mission — helping U.S. troops get their hands on the latest cutting-edge technology — then repeated an oft-used analogy. To Sweatt, McGarry was like Whitney Houston, wearing “my emotion on my sleeves,” while he saw himself as Bobby Brown — cool, calm, in control. (Text messages seen by The Standard confirm that Sweatt referred to McGarry as “Whitney,” a comparison that she says disturbed her due to Houston and Brown’s famously abusive relationship.)

The next morning, Sweatt, McGarry, and one other executive had a meeting in Sweatt’s suite. When they got there, McGarry claims, they found Sweatt hooked up to an IV, a nurse by his side, and a rolled-up dollar bill and some white powder on a table. She assumed that he’d been partying all night, and that she’d stumbled upon his recovery routine.

'The former employee and counsel have repeatedly threatened negative media attention unless Second Front pays exorbitant sums of money to her.'

A spokesperson for Second Front

The storm came a few months later, in July 2023, when Sweatt became CEO of Wilmington, Del.-based Second Front, and McGarry became his direct report. Six months into Sweatt’s tenure as CEO, he allegedly informed McGarry that one of their contractors was a “psycho” who wanted to “rape her.” A month later, per the complaint, he asked her repeatedly if she had “fucked” the company’s cofounder. By April 2024, Sweatt had eliminated the role of COO and fired McGarry without cash severance (the company offered to vest some of her shares ahead of schedule, she says).

McGarry and Second Front are now locked in a protracted legal battle, with filings in Delaware and Virginia and a pending arbitration. McGarry contends that she was fired in retaliation for speaking up about Second Front’s “boys’ club,” and that she wasn’t awarded the same opportunities as the men at the company. She’s asking for $10 million in damages, while Second Front is suing McGarry for about $430,000, claiming McGarry breached her ethical duties by misusing confidential information, making false statements, and concealing misconduct by Second Front employees and vendors.

Sweatt did not respond to a request for comment, but a spokesperson from Second Front said the company “takes all allegations — particularly those about our conduct and our culture — very seriously” and that an external law firm conducted “a thorough investigation” of all of McGarry’s claims.

“The findings were conclusive and definitive — the allegations against the company and its employees were false and meritless,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “The former employee and counsel have repeatedly threatened negative media attention unless Second Front pays exorbitant sums of money to her. Second Front looks forward to completion of the legal process, which will further establish the falsity of the allegations and shine light on the meritless claims against the Company.”

However, interviews with seven former employees corroborate McGarry’s characterizations of Second Front as a company where casual profanity and sexist remarks, recreational drug use, and organized gunplay were rampant. Interviews with employment lawyers, female military veterans, and workplace equity advocates show similar patterns throughout the fast-growing defense tech industry, which has been flooded with $155 billion in venture investments globally since 2021, according to PitchBook.

Second Front has benefitted handsomely from investors’ newfound interest in the sector. Founded in 2014 by three former Marines, the company started as a consulting business to help commercial technology startups contract with the Department of Defense. Around 2022, it gave itself a Silicon Valley glow-up, building out a platform to help pre-existing software solutions get military-grade accreditation and filling its board with venture capitalists. The company has raised more than $150 million since 2021 from New Enterprise Associates, Salesforce Ventures, and Battery Ventures, among other investors.

Defense tech is the marriage of two industries that have long struggled with gender parity. Of all defense tech deals brokered last year in the U.S., only about 10% were led solely by female founders, according to PitchBook. “It’s a combination with tech, which is already male-dominated, and then you have the veterans,” said one woman who has worked at defense tech startups. “It’s hyper-masculine.”

The band-of-brothers culture is part of why McGarry, even today, is afraid to speak out about everything she witnessed at Second Front. Many of her former colleagues at the company attended West Point or served in the military together. “They would do anything for each other, because they all were in positions where they would have died for each other,” she told The Standard. “I can’t wrap my head around that. Nor will I ever think that they would actually tell the truth for me, because they won’t.”

‘They called me the mom’

McGarry, 36, grew up in Indiana in a sprawling Italian Catholic family, with three older brothers and one younger sister. Like her parents and brothers, she went to the University of Notre Dame, where she majored in theology and gender studies, before taking a sales role in a wine company.

In 2014, a friend at Motorola suggested she try her hand at tech sales. She worked there for two years before moving to Salesforce as a senior account executive. In 2017, she took time off to finish her MBA, get married, and have a baby. About a year later, she reconnected with an old friend, Peter Dixon, a former Marine.

Dixon had gathered two fellow veterans, Nate Hughes and Mark Butler, to start a company that could help the military get its hands on the latest information technology, like software that can better manage Air Force operations and AI programs that can help officers with research. Dixon, then Second Front’s CEO, wanted McGarry to bring a Silicon Valley sensibility to the operation.

“I left Second Front scratching my head, thinking, ‘Why is it OK to talk about Adderall like it's not a drug?"

A former Second Front employee

In 2020, Sweatt joined the company as vice president of growth. In 2022, after Butler died suddenly at 55, McGarry took on more responsibilities and became COO, the only woman in the C-suite.

Sweatt and McGarry were opposites. McGarry, a fitness enthusiast with oversize tortoise-shell glasses, barely drinks, hardly stays up past 11 p.m., and tries her best to make it to church every Sunday. “Everyone kind of teased me,” she said. “And I didn’t care. They called me the mom.”

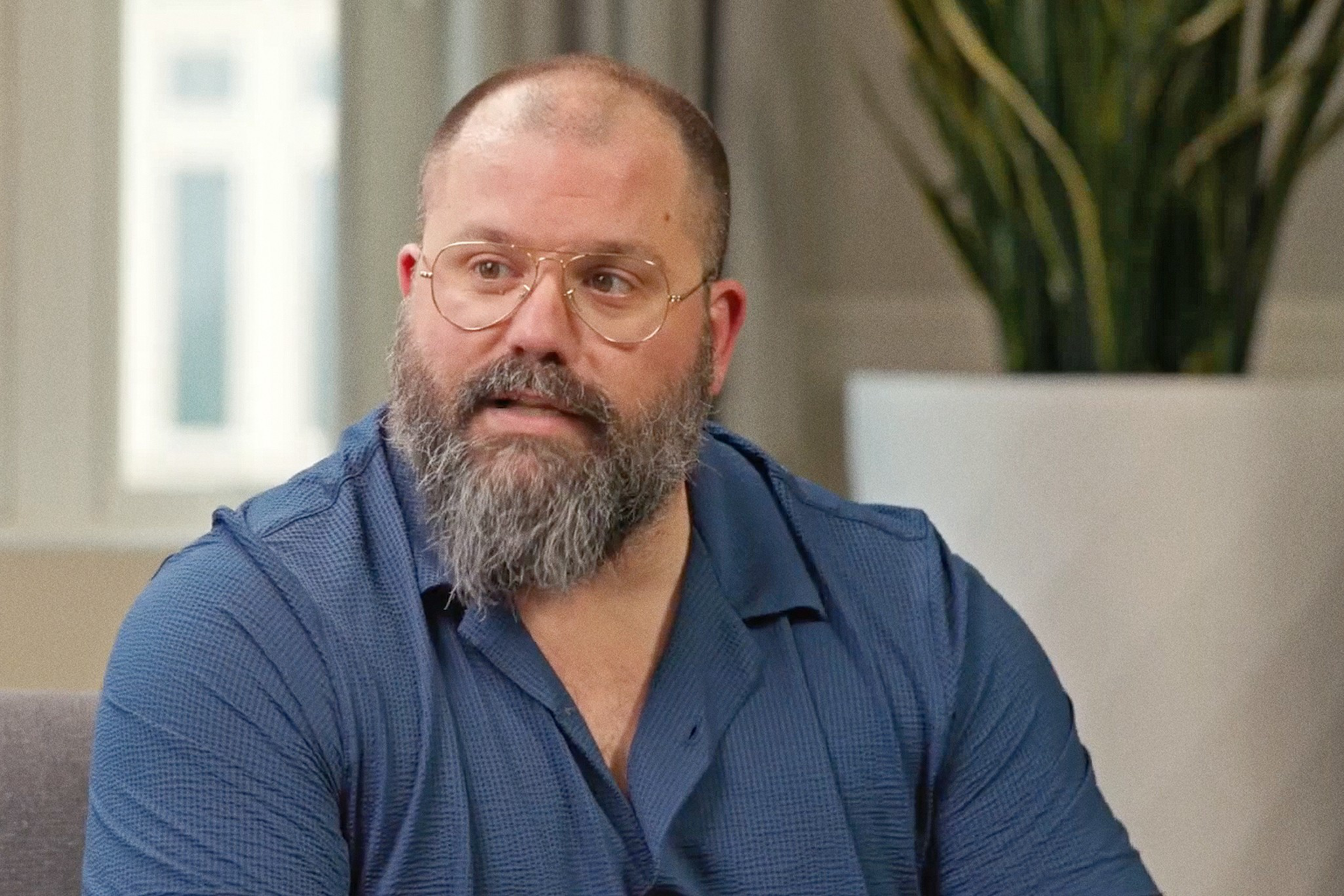

Sweatt, on the other hand, was a whiskey-drinking, gun-shooting, burly ex-Army officer covered in tattoos. He spent this year’s presidential inauguration bopping around the most prominent Trump balls in Washington. Former employees described him as larger than life and charismatic.

Sweatt’s role quickly grew, until he was essentially running sales for Second Front. Then, in July 2023, Dixon stepped away to run for Congress in California’s 16th congressional district as a Democrat, with a campaign funded in part by Jeff Bezos. (Dixon placed fifth in the primary.) Sweatt became CEO.

It took only four months for Sweatt and McGarry’s relationship to fracture. According to her, Sweatt began canceling more than half of their scheduled calls. When they did speak, she said, he was mercurial — at times effusive in his praise, calling her the “heartbeat of the company,” and at other times critical, saying she didn’t have the experience to be COO. According to McGarry, he failed to provide examples of her underperformance in writing. Sweatt did not respond to requests for comment.

In early 2024, McGarry says, she complained to Sweatt about a “boys’ club” culture at Second Front. Six former employees agreed with her assessment. One former employee was surprised to hear so many “f-bombs” thrown around the office; several were uncomfortable with how often executives brought employees to a shooting range outside of Washington, D.C. McGarry claims that Sweatt talked frequently about using cocaine and Adderall.

While other former employees couldn’t corroborate Sweatt’s drug use, one said coworkers were open about their use of narcotics: “I left Second Front scratching my head, thinking, ‘Why is it OK to talk about Adderall like it’s not a drug?’”

Matters came to a head for McGarry in February 2024, at a fundraising event in Washington for Dixon’s congressional campaign. That night, Sweatt spent 10 minutes pressing McGarry on whether she had ever slept with Dixon, she said. “It was just a part of his personality and his humor, like, ‘Come on, come on. Just tell me. Just tell me,’” she said. “But then it just got more aggressive, to the point where he’s like, ‘Come on. You hooked up. Come on. You fucked him.’”

McGarry was fuming. “For me, it was like, is he then thinking I’m only here because I slept with the boss?” she said. She denies sleeping with the former CEO. Dixon did not respond to requests for comment.

Later that month, McGarry says Sweatt floated the idea of not having a COO at all, saying he wasn’t sure the position was necessary or that she had the experience for it. Others at the company were sympathetic to Sweatt’s assessment; several former employees described McGarry as seeming underwater with the new responsibilities. McGarry argued that other executives, like Chief Strategy Officer Enrique Oti and Chief Revenue Officer TJ Rowe, had never before held those titles but were given the chance to grow into their roles.

Without telling McGarry, Sweatt called her husband and arranged for the couple to go on a five-day, all-expenses-paid trip in March (they chose Cabo San Lucas, Mexico). He told her it was a reward for her good work. When she came back, however, Sweatt’s tone veered from appreciation to suspicion. She recalls him calling her and asking, “Are you telling people that I can’t fire you because you know I do cocaine, and you’re the only woman here, and I had an affair?”

McGarry had seen evidence of drug use but says she had no knowledge of any affair. She assumes he was referring to a conversation she had with coworkers in which she remembers expressing that firing the only woman in the C-suite would be a “bold move.”

In April, McGarry says Sweatt invited her to a cigar lounge, in the same building as the team’s preferred shooting range, where he suggested that, as the “heartbeat” of the company, she should be chief culture officer. She told him she would have to hear more details about the job, as the role didn’t exist at the time.

On April 30, Sweatt fired her without severance.

‘DEI has died a quick death’

There’s a well-documented tidal change underway in the tech industry, and McGarry is among those caught in the undertow. While the Silicon Valley darlings of yesteryear are laying off employees en masse, defense startups like Joe Lonsdale’s Epirus and Trae Stephens’ Anduril are raising blockbuster funding rounds and building out megafactories.

After years of social apps and crypto booms, startups looking to improve the military represent a “good quest,” in the words of Stephens (opens in new tab). That’s why McGarry took Dixon’s offer at Second Front in the first place. “I’m so grateful to be able to say that because of Second Front, I was able to serve my country in a unique way,” she said.

But as tech and defense merge, so do two cultures steeped in masculinity. Former Arizona Sen. Martha McSally, who joined Second Front’s board shortly after McGarry’s firing, was one of the few female Air Force fighter jet pilots in the 1990s. She wrote that “fitting in and being one of the guys is a valuable survival and success strategy,” involving “lots of alcohol, profanity, making sexually inappropriate jokes, and singing raunchy bar songs.”

'I think companies are emboldened to move forward with litigation and are less worried about tarnishing their image.'

Navruz Avloni, attorney

In his most recent book, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth rages against “woke” generals, saying diversity, equity, and inclusion policies have made the military “effeminate.” One former Second Front employee said that attitude extended to the company. “DEI has died a quick death,” she said.

Before being fired last year, Sweatt discovered that McGarry had created a private Slack channel for women employees at Second Front, where they shared articles and tips for balancing motherhood with work. She said Sweatt called the channel a threat to the company’s culture and claimed it was “inappropriate” for her to maintain a private Slack channel, since it implied that she might favor women employees.

“I was like, What are you talking about? There’s a veterans channel. Like, why does it matter?” she said. She eventually agreed to make the channel public.

In December 2023, as her relationship with Sweatt was deteriorating, McGarry met up for dinner with Tony DeMartino, a Second Front investor, veteran, and Sweatt mentor. McGarry liked to get DeMartino’s feedback on the company’s strategy and, that night, wanted to know how she might better communicate with her CEO, particularly since Sweatt and DeMartino share a military background.

In her legal filing in Virginia, as well as in a report to the board after she was fired, McGarry accused DeMartino of assaulting her that evening at the restaurant. She would not share further details of the incident, but in September 2024, Second Front offered her a settlement on the condition that she sign an agreement to release DeMartino from all claims she had against him. McGarry turned down the offer. Through his attorney, DeMartino declined to comment.

‘We saw the same thing last term’

Lawsuits like the ones McGarry is pursuing against her former employer are always an uphill battle, requiring immense time and money to challenge a company with vastly outsized resources. But the current political climate may make it even harder. “There’s definitely a real chilling effect that’s happening overall,” said Jaime-Alexis Fowler, founder of Empower Work, a nonprofit that supports employees in toxic workplaces.

Navruz Avloni, a lawyer who has represented women in tech in suits against their employers, said we’re more likely to see cases like McGarry’s go to trial, rather than being settled, under the second Trump Administration. “I think companies are emboldened to move forward with litigation and are less worried about tarnishing their image perhaps,” she said. “I mean, we saw the same thing last term.”

It will be some time before McGarry’s legal battles with Second Front are over. In the Virginia case, in which lawyers for the company argued that arbitration should be moderated by one person instead of a panel of three, a judge ruled in McGarry’s favor. She still has a filing against the company in Delaware, where, as a shareholder, she’s requesting access to some of Second Front’s financial statements and records, in part to see if the company made misrepresentations to its Series C investors about her ongoing litigation against the firm.

The biggest, most important case will be the arbitration, with both parties suing the other for damages. Her lawyer expects that the process will stretch well into 2026.

Meanwhile, McGarry has been tentative to reenter the workforce full-time. As for if she’d work in defense tech again? “No,” she laughed, her voice cracking. “This crushed me.”