Mid-Market has earned its reputation as the city’s no-man’s-land. Despite attempt after attempt to rehabilitate the area (see: new IKEA, dead Whole Foods, abandoned Twitter HQ), it remains mostly empty retail spaces, shuttered offices, and many people visibly high on drugs.

But to 30-something German entrepreneurs Jakob Drzazga, Christian Nagel, and Christian Peters, this state of affairs presented an opportunity: the chance to buy a 90,500-square-foot, 16-floor building on the corner of Sixth and Market for only $11 million.

In March, the three friends, with backgrounds in venture capital, fintech, and real estate development, pooled their savings, called in favors, and secured a loan from a private debt fund to buy 995 Market St., a former WeWork facility and headquarters of the Burning Man Project. Though the price was almost double what the building sold for in 2023, it’s a fraction of the $62 million (opens in new tab) it was assessed at back in 2016.

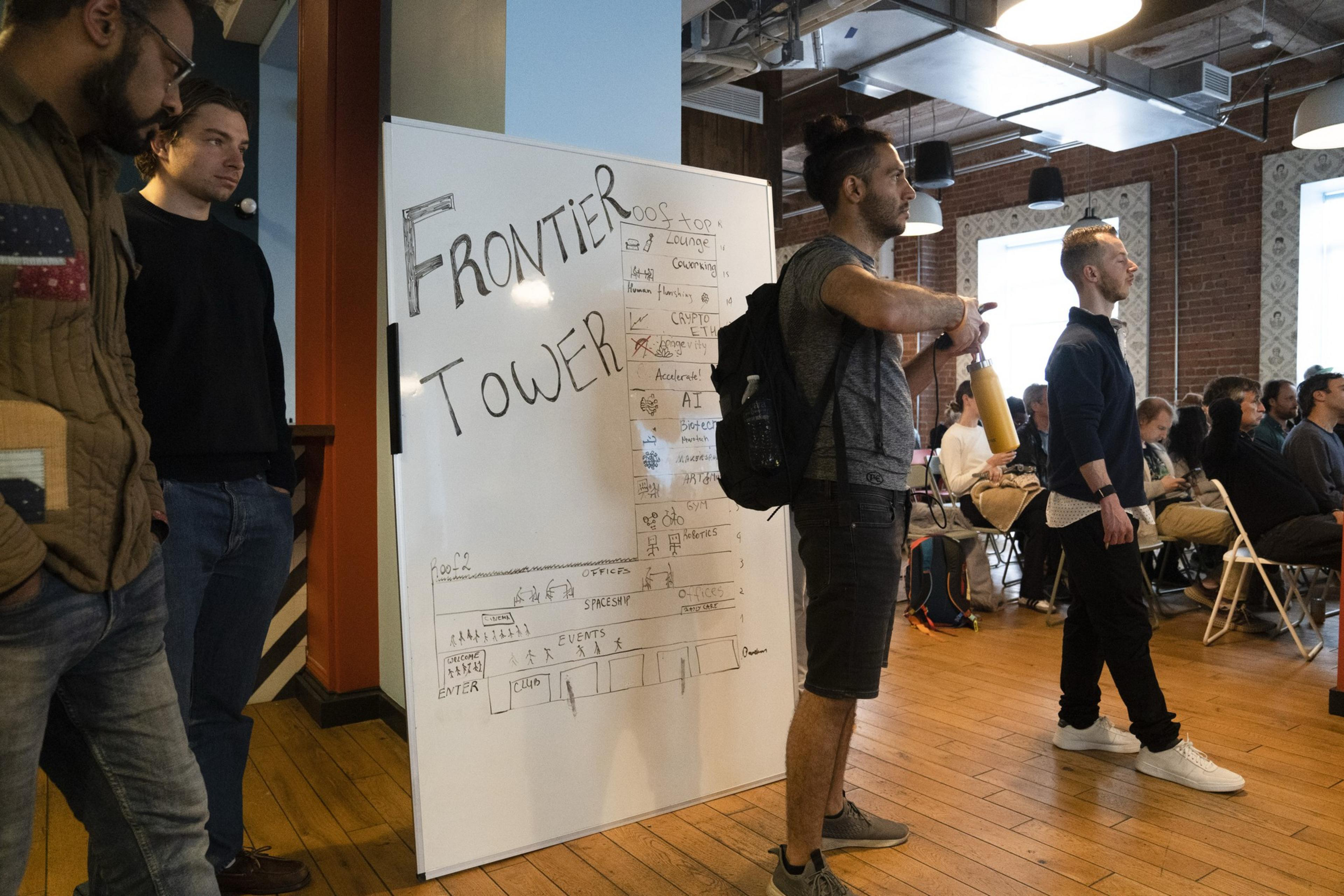

Their plan? To build a membership-based “vertical village” for cutting-edge research, with each floor devoted to a different 2025 tech buzzword — neurotech, cryptocurrency, AI, longevity, biotech — and of course, plenty of space for raves and art projects. The name of this accelerationist utopia in the sky: Frontier Tower.

“We wouldn’t have been able to afford the real estate five years ago,” said Nagel. “If the market weren’t so soft, no one would’ve taken a meeting with ‘these crazy guys from Germany.’ But given the number of vacancies, people were super open.”

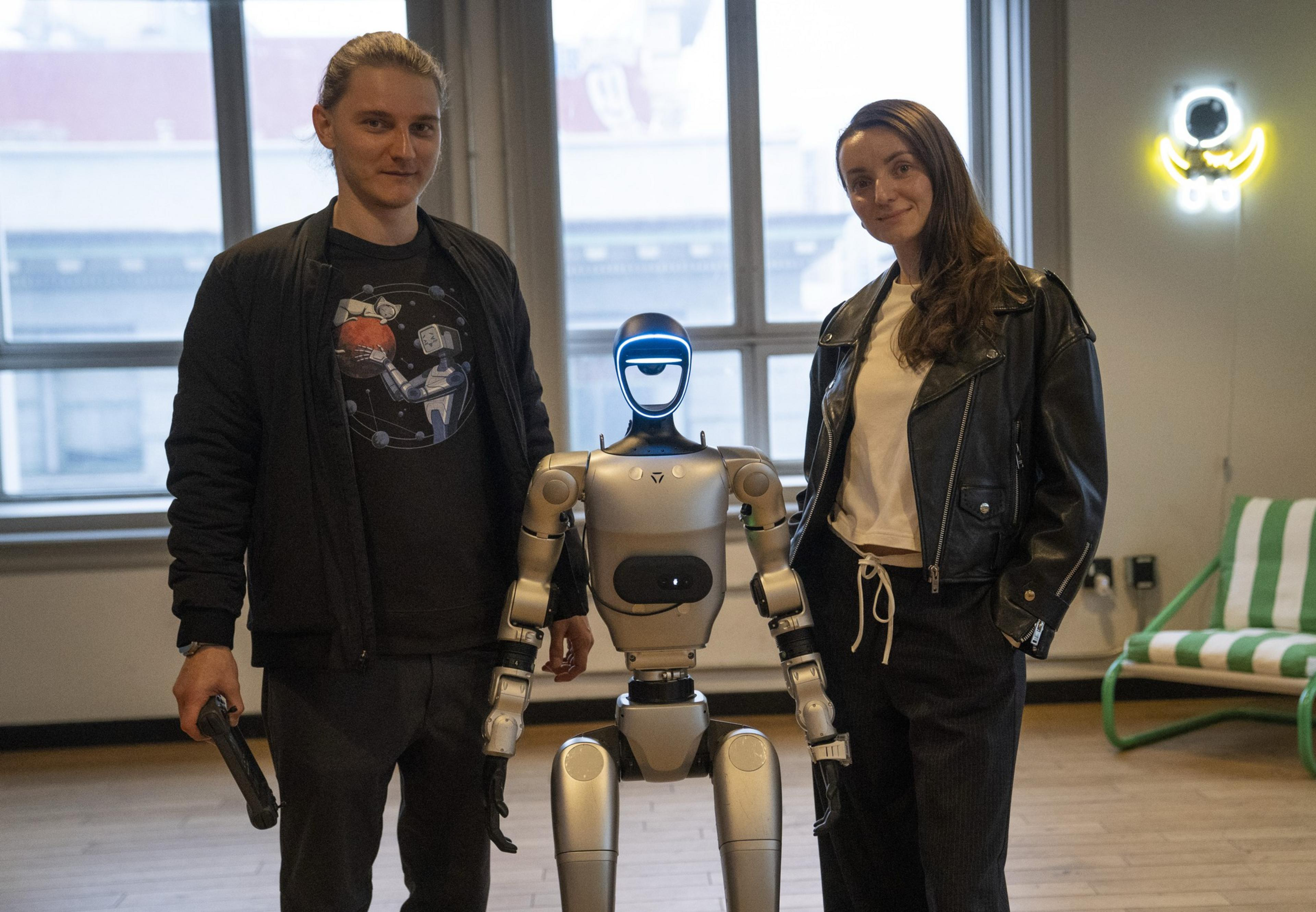

For the past two months, they’ve been building buzz, holding events in the barely furnished building and offering tours to prospective members — complete with meet-and-greets with a friendly humanoid robot on the fourth floor. Over several visits this spring, The Standard got an early peek at this village of techie dreams taking shape.

‘A lot of potential in this neighborhood’

An officer from the San Francisco Police Department stopped by Frontier Tower’s weekly town hall meeting Monday night to help current and potential members understand the area. “The fentanyl crisis has primarily been down here, associated with that adverse community,” Kevin Knoble, acting captain for the Tenderloin, told the crowd. “We [try] to interrupt that activity … but it’s a steep and hard path.”

Knoble urged attendees to have empathy for the neighborhood’s struggling and unhoused residents. “Market Street is coming back to life. Thank you for participating in that,” he told the crowd. He was honest about the area’s flaws. It’s personal to him, he said; his nephew recently died from a fentanyl overdose.

The location did not deter Constance Li, the 35-year-old director of the nonprofit AI for Animals (opens in new tab). In December, she committed to paying $190 a month for her Frontier Tower membership, sight unseen.

“At a regular coworking space, maybe you randomly bump into relevant people,” she said. “But here, if I have a biotech question, I just go to [the biotech] floor and ask somebody.”

Plus, she lives in the Mission, which has its own challenges, she said. The tower has plentiful perks for members, including a coworking lounge, gym, meditation space, events floor, rooftop area, and a storage space and nightclub in the basement.

Li works there one or two days a week and said she might come more when there’s more furniture. And yes, the furnishing is a work in progress, admits Nagel. Most coworking spaces spend months, and millions of dollars, zhuzhing up the space before letting people in, but that’s not the Frontier Tower way. “It builds community when we are literally building desks together,” he reasoned.

Each floor has two designated leads, who receive $2,000 to outfit their space — about the price of three heavily discounted Herman Miller chairs. Given these miniscule budgets, members have taken matters into their own hands, scouring Facebook Marketplace for bargains on desks and cabinets and donating spare furniture from their homes. Trellis, (opens in new tab) a coworking spot two blocks away, loaned chairs for the tower’s first town hall.

Despite the minimal furnishings, the building is surprisingly move-in ready, Nagel said. For that, he credited the former tenant, WeWork, which outfitted most floors with upscale light fixtures, soundproof phone booths, high-end speakers, and vintage wallpaper.

Inside the tower

Frontier Tower has an L-shape, with the first three floors significantly larger than the rest. The second floor, aka “The Spaceship,” serves as the hub for town halls and other events. Vitalik Buterin, the cryptocurrency ex-billionaire (opens in new tab), cohosted a panel on futurist cities (opens in new tab) there in March. A corner of the Spaceship is designated for a future day-care center. Nagel, who has a 5-year-old, is leading the charge on making the tower friendly for working parents. “This is a village, and children belong in a village,” echoed Drzazga. (The founders hope to secure permits to add co-living spaces; Nagel says they are aiming for city approval by 2026.)

Take the elevators or stairs up two floors from the Spaceship, and you reach the fourth-floor robotics wing, headed by Xenia and Vitaly Bulatov, a husband-and-wife team from the East Bay with backgrounds in growth marketing and R&D. Since launch, they’ve welcomed 17 members, a mix of solo founders and small startups, like Carbon Origins (opens in new tab), which develops VR remote tools for robots, and Robonomics, whose humanoid is housed here. (opens in new tab) The floor has a capacity of 80 people, said Xenia, who has dubbed it the “Cyberpunk Lab.”

Since robotics companies tend to be located in warehouses in the city’s outskirts — inconvenient for investors, according to Xenia — the central Mid-Market location is part of the draw. “This is a really accessible place … we’re 10 minutes away from Union Square,” she said. “There is a lot of potential in this neighborhood.” The Bulatovs keep a $50,000 Unitree Robotics Humanoid G1 and a $75,000 Boston Dynamics Spot dog locked in their office, available for members to borrow.

Only Cyberpunk Lab members have unfettered access to the floor, via a mobile app that also works on the tower entrance and in the elevator. Nonmembers must be admitted at the front desk.

In April, Elliot Roth, founder of the BioPunk community laboratory in the Design District, packed up his centrifuges, microscopes, and various machinery and moved to the eighth floor of Frontier Tower, the biotech floor. His goal: to use synthetic biology to solve real-world problems.

Roth’s working on getting his lab BSL-2 certified, which would allow researchers to safely study bacteria and viruses that carry a moderate risk. As of last week, some of his expensive equipment was still in boxes.

Laurence Ion co-leads the longevity unit on the 11th floor. One member of his wing is building out a hyperbaric oxygen therapy startup, offering sessions to residents, and another is considering offering members IV drip therapies. On June 20, this floor will transform into “Viva Frontier,” a six-week “pop-up village” inside the vertical village, which organizers are marketing for “pioneers in longevity, AI, crypto, and more.” The idea is a teaser for Ion’s vision for Viva City (opens in new tab), a permanent community that would aim to “make death optional” — tropical location TBD.

Though Frontier’s furnishings are sparse and the occupancy rates low — there are currently 200 members, not including office renters, with room for at least several hundred more — the excitement in the tower is palpable.

On a Tuesday night in April, I met a Gen Z engineer in the elevator, frantically hopping from the 14th floor to the 8th; they couldn’t decide between the psychedelic-enabled consciousness research event or the neurotech salon, hosted by the Foresight Institute. They’d started the day with the longevity lunch on 11. “There’s too much going on. I have to start doing my own work at some point.”

The final frontier for Frontier Tower: making a profit. Nagel and Drzazga hope a mix of “citizen” memberships at $1,980 to $2,280 a year, corporate sponsorships, and rentable offices on floors two and three (priced at $700 to $2,800 a month) will make Frontier Tower solvent. They receive rent from CVS, which leases but does not use the ground floor and will not accept a buyout. The third floor of private offices is at capacity, Nagel said.

The Standard’s back-of-the-napkin math suggests that if they get each floor to 70% occupancy, they’ll be able to pay their taxes and keep the lights on. But they’re nowhere close to that now.

“We’re focused on creating value and community, and I believe the rest will come,” said Nagel.