Sometimes, San Francisco Immigration Court looks less like a federal venue for life-or-death decisions than a poorly designed indoor playground for toddlers, or an austere high school office where students wait to meet the principal.

Teenagers face judges alone. Children crawl around the floor as their parents sweat under the gaze of a system most of the U.S. public never has to see.

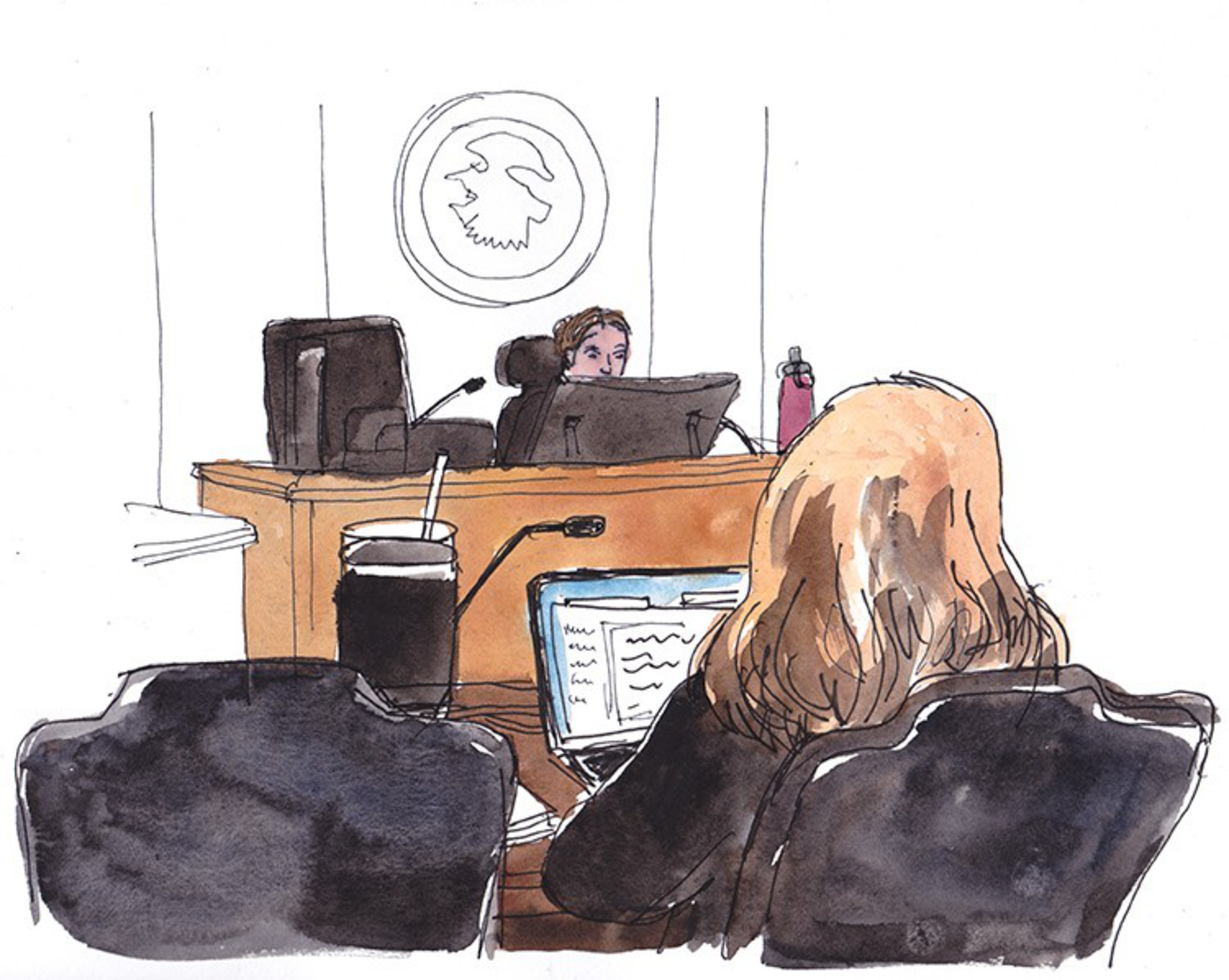

The court prohibits photography, video recording, and audio recording, so even news stories from the proceedings are unable to show what it looks like when immigrants face the court judge.

The Standard wanted to make the invisible visible, so we brought illustrator Dan Bransfield with us to court for two days to document the people behind the headlines. Appearances at immigration court frequently last less than 10 minutes, so Bransfield had to draw and color quickly. His images capture the hectic feeling in the court. For this story, we are using only the first names of people facing deportation, referred to in court as “respondents.”

On a recent Thursday at 630 Sansome St., four families with babies and toddlers pack the courtroom of Judge Patrick O’Brien. The children are crawling along the carpet, standing on the wooden pews, and rubbing their sticky hands across the walls.

“It’s fine if kids want to move around the courtroom as long as they’re quiet,” the judge says.

O’Brien is overseeing a “master calendar hearing,” wherein respondents have their first chance since crossing the border to request asylum or other means to avoid being sent out of the country.

The judge explains through a Spanish interpreter what respondents should expect from the proceedings. He advises everyone present, all of whom are representing themselves in court, to get lawyers.

“Sadly,” O’Brien explains, “immigration law is difficult. It’s easy to make a mistake. And if you make a mistake, you could be deported.”

As if on cue, the children’s voices swell into a chorus of whining that drowns out the judge’s words. O’Brien turns to his clerk. “This suddenly went from an easy masters to a difficult one,” he says, referring to the calendar hearing. Embarrassed parents carry two noisy children into the hallway, somewhat quieting the courtroom.

The loud babbling of one toddler persists. His name is Liam, and in his Mickey Mouse jacket, he is as cute as he is disruptive. O’Brien tries a grandfatherly tone: “Liam? Liam? We need you to be quiet for just a few minutes.”

Standing on a pew with his back to the court, Liam ignores the judge, flicking his tongue in and out to make a noise that sounds like “glug.”

The judge decides to handle the case of Liam’s mom, Nubia, first. He advises her that finding child care for her next court date would allow her to better focus. She’s a single mom with no one to watch her boy, she says.

Soon, Paula and Andrea, two single women who don’t know each other, are called before the judge together. O’Brien’s tone becomes sober. The government has moved to dismiss their cases, he tells them.

This is a tactic (opens in new tab) the Trump administration has been using in immigration court to fast-track asylum applicants for deportation. Once the government moves to dismiss a respondent’s case, Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers usually detain them within minutes of leaving the courtroom.

The women are confused. The judge explains, “I’m pretty sure you won’t be coming back to my court.”

Andrea, dressed as if she were at a job interview, tells the judge in Spanish, “I would like to have the opportunity to explain my case, why I left my country, and why I can’t go back.”

“We’re not going to do that today,” the judge responds. Paula begins to sniffle. “I highly recommend you get a lawyer,” O’Brien says.

His tone shifts again, to the grandfatherly one he used with Liam. “It was nice to meet both of you. I look forward to seeing you again. If not, I wish you a lot of luck.” Both women openly weep.

When Andrea and Paula leave the courtroom a few minutes later, ICE officers are waiting. They handcuff the women and take them away.

A 10-minute walk from O’Brien’s courtroom, San Francisco’s bigger immigration court inhabits a few floors of an office building at 100 Montgomery St. Prior to a court session, Judge Karen W. Schulz chats with a Spanish interpreter: “Someone told me I have the best toys for kids in my court. I said, ‘Yeah, I have the juvenile docket!’”

Unlike in other courtrooms, where children may be offered coloring books, if anything, Schulz keeps three baskets overflowing with toys, stuffed animals, and books.

Here, underage immigrants face the court alone, without their families. Half a dozen teenagers sit waiting their turn. Two boys wear angular, faded haircuts and skater shoes. A pair of sisters in hoodies sit huddled together.

The most stylish boy is Elder, a preteen wearing a red-and-white tracksuit, a fuzzstache, and an Edgar haircut. His lawyer, who works with a nonprofit, tells the judge that Elder speaks Mam, an Indigenous language from the highlands of Guatemala. Elder dons headphones and listens as the judge speaks to him via a Spanish translator.

“Do you speak Spanish as well as Mam?” the judge asks.

“Yes, but Mam is better,” Elder says in heavily accented Spanish.

A Mam translator is connected via Webex, a videoconference platform used by federal courts, and Elder has a 10-minute hearing, then is sent away with a scheduled follow-up court date.

Elder’s lawyer drove him to court herself, she explains outside the courtroom, because she didn’t want his parents to risk coming and being detained by ICE. If she hadn’t picked up Elder’s case just the week before, she would have had time to request that he appear via Webex, as she’s advising all of her immigration clients to do.

These days much of the court’s business involves remote participants, with not only frightened asylum seekers but translators and lawyers for the Department of Homeland Security appearing via a big flat screen, which sits permanently perpendicular to the judge.

Multiple underage respondents attend court this way, including Danny and Ludwin. The tiny downcast faces of the brothers appear on the screen alongside that of their lawyer, who, positioned closer to the camera, looks unnaturally large next to them.

The last task for a judge during master calendar and juvenile docket hearings is usually dealing with absent respondents. These are immigrants who were supposed to show up in court that day but did not. One by one, Schulz and the attorney for DHS go through the cases.

First up is a 16-year-old girl who appeared in court in 2023 and 2024 but whose latest notice to appear was returned as undeliverable. The DHS lawyer, a blond woman with a quiet voice, asks the judge to deport the girl in absentia. “I grant the government’s request to deport in absentia,” Schulz responds.

Quickly, she makes the same somber pronouncement for four other children: a 15-year old boy whose father refused to bring him to court, a 13-year-old boy who entered the U.S. unaccompanied at age 9, and a brother and sister who had previously come to court from a foster home. Schulz orders them all deported in absentia.

No one knows why the kids didn’t come to court.

Schulz’s posture changes as she orders the deportations. She hunches in her seat, head hung low. Her previously warm voice lowers to a near rasp: “I grant the government’s request to deport in absentia.”

Suddenly, a reprieve. A volunteer lawyer in the gallery has managed to reach one of the respondents who hadn’t shown up to court, a 19-year-old named Nicole. Her voice pipes into the courtroom via Webex.

“Did you know you were supposed to come to court today?” Schulz asks.

“Sí,” Nicole responds.

“Why didn’t you come in?” the judge asks.

“I was afraid of the ICE roundups,” Nicole says in Spanish.

Schulz looks at the DHS lawyer and shakes her head. When the judge asks what she wants to do, the lawyer says she’s fine giving Nicole a continuance.

“The government attorney is being very generous by not asking for you to be removed,” Schulz explains. “But if you don’t come to your next court date, I will probably order you removed in your absence.”

Nicole lets out a deep sigh of relief that gives way to audible crying. “Gracias,” she says over and over through sobs. “Gracias.”

For first-time visitors to immigration court, it can take a moment of deliberate effort to grasp that a toddler or baby in the courtroom may be the target of legal action.

A few days later at the Montgomery Street court, a 3-year-old named America is not paying attention as immigration Judge Michelle Slayton informs her parents of the charges against them of illegal entry to the U.S. Instead, she fixates on the low wooden fence that separates the gallery from the court well. Wearing a bright-yellow dress that occasionally exposes her diaper, America runs up and down the length of the fence, playing peek-a-boo through the slats with anyone willing to look her in the eye.

The family fled their home in the violent Mexican state of Michoacan after receiving threats from gangs, America’s mother explains after the hearing. At the time the family crossed into the U.S., America was 4 months old. Returning to Mexico would put all of them, including the little girl, at risk of being murdered, she says.

But for now they can safely remain here. The hearing is their first, simply a chance to orient themselves and prepare for a years-long legal process to seek the right to stay.

As Slayton schedules the family’s next court appearance, America happily reenters the gallery through the swinging door, then turns around and crosses back into the court well. She does this repeatedly, and carelessly, sure that the fence will open again.