A startup founder and a rabbi walk into a hotel to talk about killer robots.

It’s not a joke. Last month, while the “All-In” podcast hosted an AI summit down the street, Mike LeBlanc, cofounder of San Francisco-based robotics company Foundation, settled into a leather chair at Washington, D.C.’s Waldorf Astoria.

He was there to pitch Rabbi Yehuda Kaploun, the Trump Administration’s special envoy to combat antisemitism, on the benefits of using humanoid robots in the military.

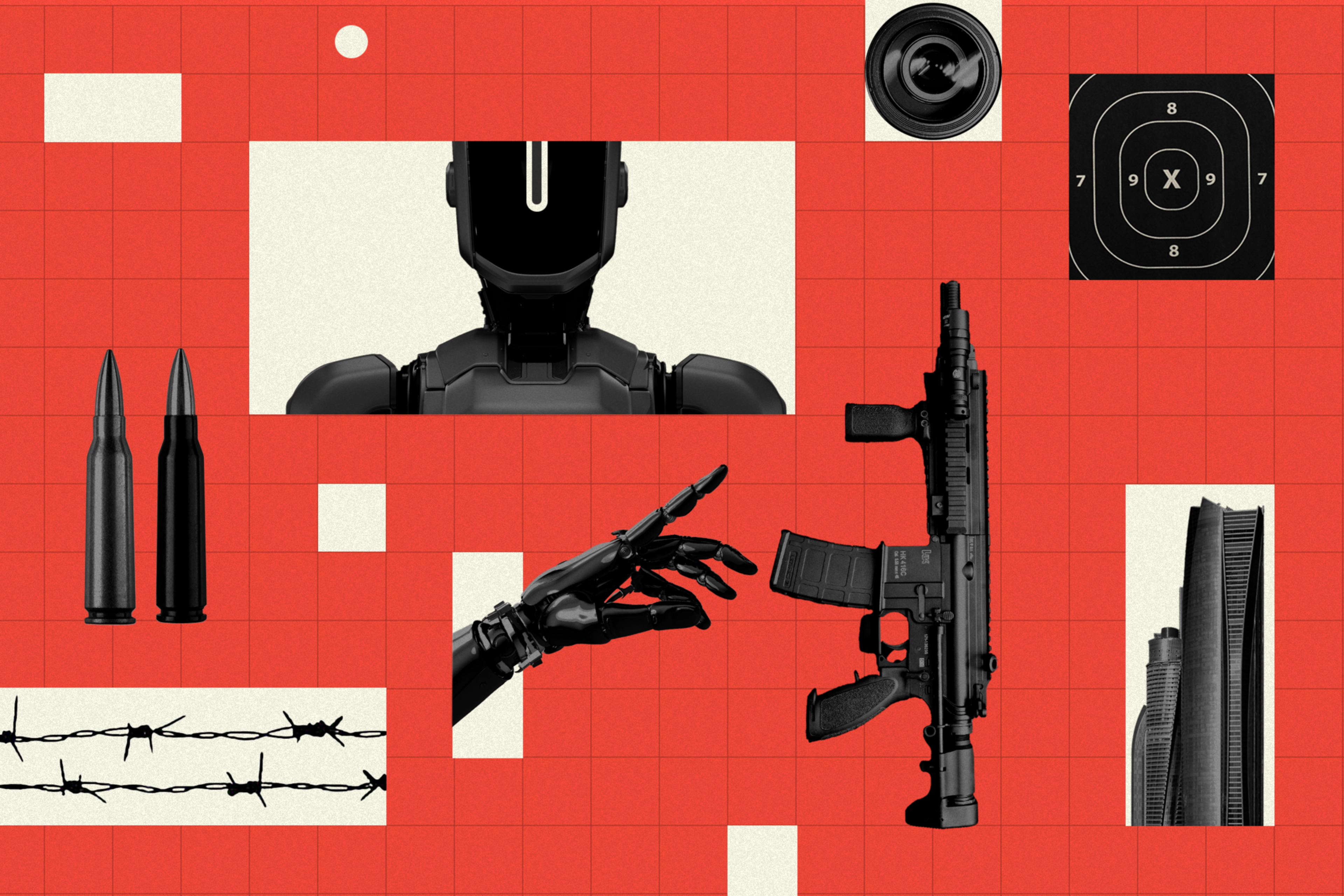

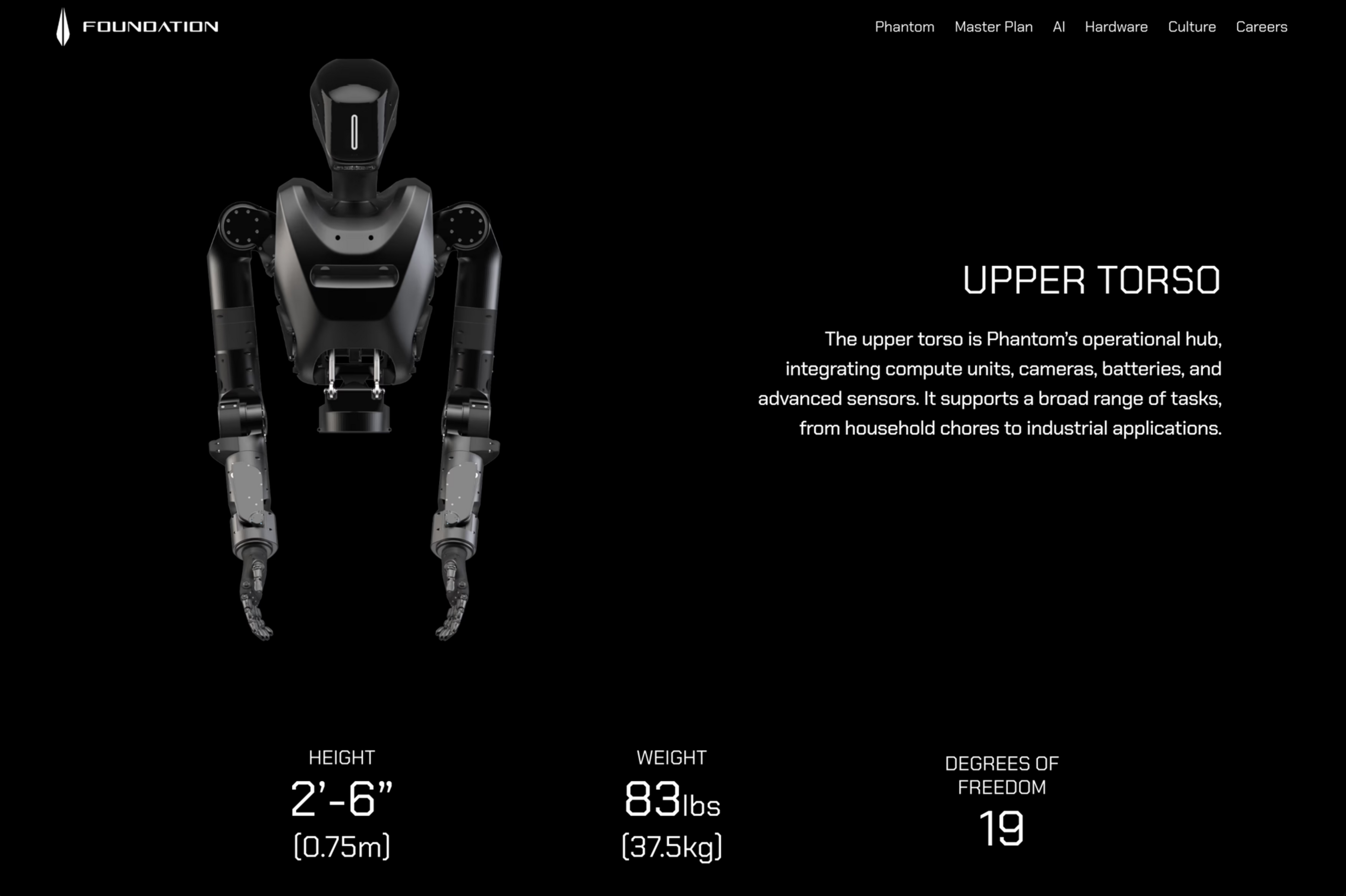

During their conversation, LeBlanc explained Foundation’s main product: a humanoid named Phantom that can be used for menial factory work — or, if desired, defense purposes — for $100,000 per year. Unlike its competitors, LeBlanc said, Foundation is open to attaching guns or other weapons to its robots.

The pair spent an hour brainstorming how the Trump administration could use the startup’s robots for defense. Perhaps the president would like humanoid security guards protecting his envoys and diplomats? Or sentries defending the nation’s synagogues?

Kaploun later connected LeBlanc with a representative from the Department of Homeland Security, with whom the Foundation executive discussed a different idea: sending Phantom guards to the border to patrol for immigrants. The startup’s conversations with the government are at an early stage, LeBlanc told The Standard, and Foundation is not currently testing a weaponized version of its robots. However, that could change soon.

Foundation, founded last year by LeBlanc, Arjun Sethi, and Sankaet Pathak, is entering a crowded field in the race to create humanoid robots. Well-financed competitors like Tesla, Figure AI, and Unitree Robotics are working on humanoids that can assemble cars, care for the elderly, install solar panels, and even shake cocktails.

But while many robotics firms have refused to militarize their robots, Foundation has won over investors with its stated ambition to sell humanoid units to the Department of Defense. This commitment puts the company at the intersection of two Silicon Valley fixations — robotics and military tech —while bringing the prospect of a battlefield-ready Terminator closer to reality.

The 45-person startup is in talks with investors to raise upwards of $150 million, likely to build out a manufacturing facility. A portion of that cash is coming from sovereign wealth funds in the United Arab Emirates.

Humanoids — robots in human form — are starting to be used at factories nationwide; Morgan Stanley estimates there will be more than 1 billion in operation globally by 2030. Investors have poured a record $2.7 billion into humanoid robotics so far this year, according to PitchBook. More than half of the top robotics firms are based in China.

These companies are capitalizing on increasingly cheap components and recent advances in generative AI, which now let humanoid robots learn quickly and cheaply by watching videos of humans or other robots performing tasks.

So far, many humanoid companies have forgone military contracts. Humanoid startup Figure AI, reportedly in talks to raise $1.5 billion, published a “master plan” in 2022 in which it swore it would not “place humanoids in military or defense applications.” And when Tesla needed parts from China for its Optimus humanoids, Elon Musk had to assure the Chinese government that the components would not be used “for military purposes.”

Foundation is taking the opposite tack. LeBlanc said the company has already inked $10 million in defense contracts, including with the U.S. Air Force to use its robots for refueling and maintenance. The company is preparing to ramp up production, deciding between three states to build a factory, including in Ohio — which has thrown incentives at startups that set up shop in the state.

If Foundation has a say in the matter, the era of a humanoid-filled military is upon us. “It’s an absolute dereliction of duty not to have your robots be willing to fight for America,” LeBlanc said.

‘Are you a vegetarian?’

LeBlanc served as a Marine for more than a decade. Then, in 2019, he cofounded a robot security guard startup called Cobalt and made sure a third of jobs went to veterans to help them adjust to civilian life.

He spent more than four years building Cobalt before selling it last summer for an undisclosed amount to entrepreneur Dean Drako, who has founded a range of technology companies. After seeing the challenges of hardware development firsthand, LeBlanc vowed never to go into hard tech again.

It was a short-lived pledge. About a year ago, a mutual friend introduced LeBlanc to Pathak, who was looking for some insight into running a robotics company. His last gig was as CEO at Synapse, the banking software startup that lost tens of millions in customer funds last year.

Originally, LeBlanc insisted he would only give Pathak advice on how to take robots to market. But then LeBlanc's mentor, Sequoia Capital investor Alfred Lin, told him that humanoids were having a moment in the Valley. If he developed his own, he’d have “a shot at being a billionaire,” LeBlanc recalled Lin saying. “You’ll never have that shot again.”

Pathak called up his old friend, Sethi, to ask for fundraising advice; the venture capitalist responded that he, too, had been fascinated by humanoids and wanted to help build the company. So Pathak, LeBlanc, and Sethi joined forces to buy Boardwalk Robotics — a small startup based in Pensacola, Florida, that had developed a humanoid named “Alex” — for an undisclosed amount. The trio moved the company to San Francisco, renamed the robot “Phantom,” and were off to the races.

From the start, Foundation intended to sell to the military. “Defense is crucial for building and safeguarding the infrastructure necessary for making life self-sustaining,” Pathak wrote on X. “Unlike most humanoid robot companies in the U.S., which have committed to non-weaponization, we believe it’s essential for our robots to master these tasks to support human expansion.”

Pathak’s ambition veers into sci-fi: He believes humankind will eventually need a robotic labor force to work on the moon or Mars. Foundation came back down to Earth after the founders toured factories and realized that commercial customers would lock down contracts faster. At least one customer is an auto-parts manufacturer, which Foundation declined to name.

LeBlanc said Foundation is in high-level talks for contracts with several defense companies, including Anduril. The hope is that, with humanoids, Anduril can save on labor and undercut defense behemoths like Lockheed Martin. Representatives for Anduril didn’t respond to a request for comment.

When Foundation employees asked the founders about the company’s stance on weaponization, LeBlanc responded with his own question: “Are you a vegetarian?”

“If you are a meat-eater who doesn't like that we kill the animals, I don’t respect that position,” he recalled saying to employees. “So if you enjoy the security that we have in the United States, I want to give all the tools that we can to our war fighters.”

‘They’ve gone crazy’

As recently as 2021, it was anathema in Silicon Valley to work on military or homeland defense projects. That year, after someone leaked a video of a Brinc drone tasering an actor playing an illegal immigrant, the backlash was so intense that the company’s founder vowed never to weaponize his drones again.

Companies developing humanoids largely followed suit. In 2022, six companies, including Unitree Robotics, Agility Robots, and Boston Dynamics, signed a pledge not to weaponize their general-purpose robots.

But the last two years have proved that forgoing military contracts was a loosely held moral line. In his conversation in the Waldorf with Kaploun, LeBlanc lambasted competitors who wouldn’t consider arming their humanoids: “They’ve gone crazy,” he said.

In addition to Trump’s push to onshore American manufacturing, the war in Ukraine and increased tension with China have galvanized investors to fork over $28 billion to defense tech startups so far this year — on track to nearly double 2020’s total, according to PitchBook. Nowadays, Google rakes in hundreds of millions in defense contracts, while drone startups like Neros were launched specifically to help Ukraine on the battlefield.

However, using humanoids in war settings can create unknown moral hazards, according to Wendell Wallach, a bioethicist and coauthor of “Moral Machines: Teaching Robots Right from Wrong.” He said military commanders argue that robots are “just the extension of their will and intention.”

“Damn the fact that once in a while, these robots will act in ways we never intended and cause serious damage,” Wallach said. “That’s just the price of war.”

Take a humanoid robot patrolling a battlefield. “How would a robot know that somebody wielding a knife over a fallen soldier is a medic and not the enemy trying to kill that soldier?” Wallach asked.

Foundation’s leaders intend to limit sales for military uses, a source said, and if they believe those uses are causing the death of innocent people, they’ll do the “Elon thing,” referring to Musk’s refusal to let Ukraine use his Starlink communications network for an attack on Russia.

Julie Carpenter, a research fellow at Cal Poly’s Ethics + Emerging Sciences Group, said selling to the military is rarely that simple. She cited an example from 2016 in which Dallas police strapped a bomb to a non-weaponized robot, then used the robot to kill a suspect. “Once they have your product, they can jerry-rig it,” she noted.

As a former Marine, LeBlanc understands that working with the military brings a host of complex moral questions. But as he told Kaploun, U.S. companies can’t afford to make idealistic promises in a vacuum. “Unless your enemies make that same pledge,” he said, “I don’t think it's a great one.”