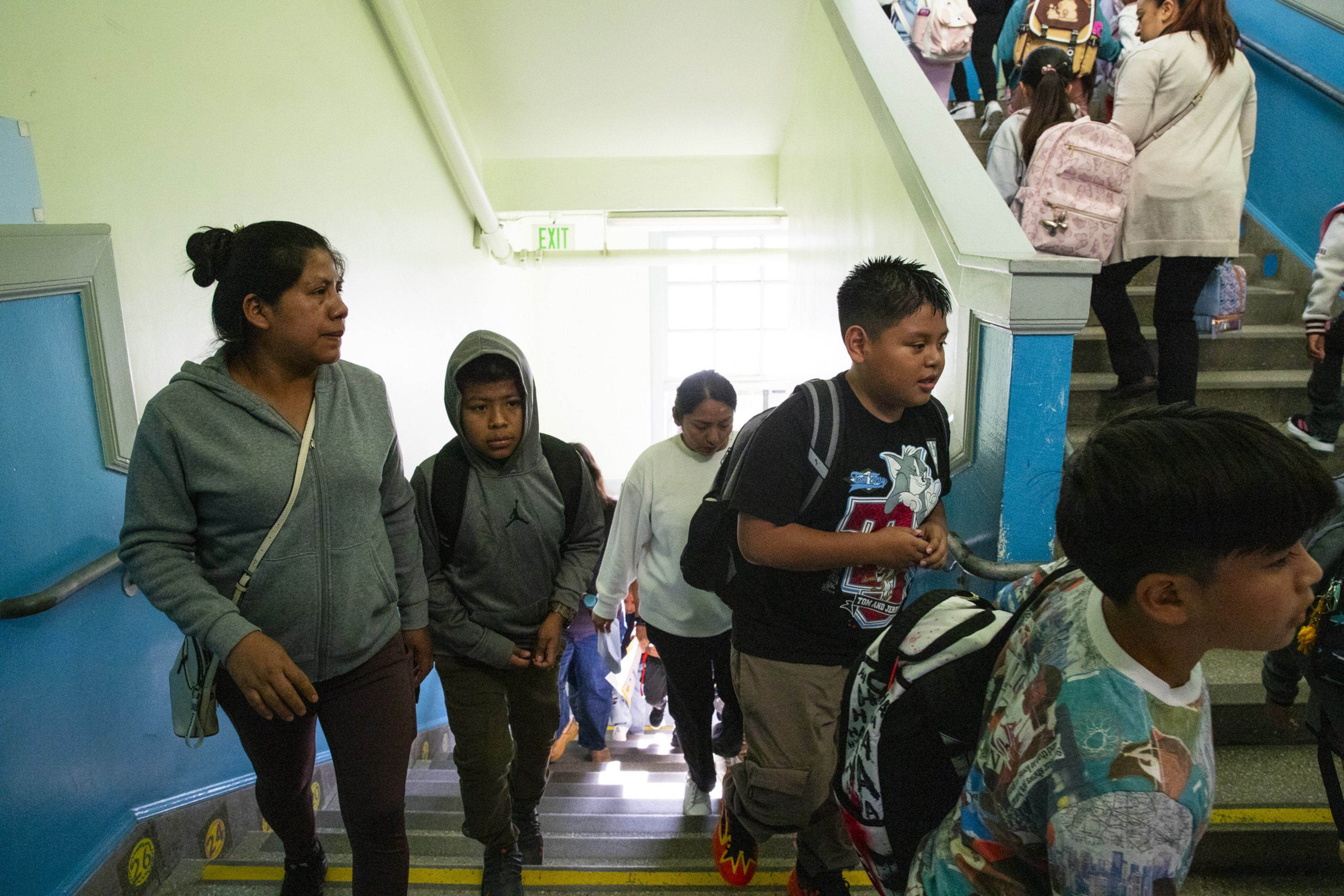

As the doors opened Monday at 8:20 a.m. for the first day of school at Mission Education Center in Noe Valley, an employee greeted families bilingually — “Bienvenido! Hello!”— while moms wiped children’s faces and dads clenched small ones’ hands.

It was a scene typical of any first day back at school: Students excited to see friends after the long summer break, parents feeling a mix of worry — and relief — that the kids are out of the house.

But alongside displays of familial love at Mission Education Center, which serves recent immigrants who speak Spanish, there was palpable anxiety. Amid President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown, parents at the San Francisco Unified School District are sending their kids back into the classroom in fear.

“We were anxious to come today,” a 32-year-old Colombian woman said in Spanish as she hauled three children into the school. The Standard is not publishing her name to protect her identity.

The woman said she came to the United States a year ago and works as a bartender but lives here without legal status.

“When [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] started their raids last year, we didn’t bring our kids to school for two weeks,” she said. “We were all scared.”

Her children have asked whether they should leave the country rather than risk getting separated, but the family plans to stay, she said. Another mother at Mission Education Center, who came from Venezuela a year ago, said she was nervous that ICE agents would be lurking nearby as she dropped off her 3-year-old.

SFUSD started the 2025-26 year with a list of issues to address, from the debate over a high school ethnic studies curriculum to a massive budget deficit that could force school closures. But for some immigrant students and their families, the Trump administration’s recent ICE sweeps in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and other California cities are the top concern.

District officials have in recent days tried to quell those worries by reiterating SFUSD’s “sanctuary” protections for its campuses. Officials do not collect data on the immigration status of students or their families. Under SFUSD policy (opens in new tab), if immigration officials show up at a campus, they will be allowed only to the front office and will receive no access to students; no student information will be shared without a warrant or court order.

“This means that our schools are safe havens where all students are welcomed and valued, and where every child has the right to attend school, no matter their immigration status or that of their family members.” Superintendent Maria Su said in a letter to families (opens in new tab) Sunday.

Su confirmed with The Standard in a recent interview that district officials have worked with Mayor Daniel Lurie’s office and community leaders to “make sure that we as a city are all on the same page” and that district staff is prepared to support students and families, “particularly those who are in fear of any type of immigration actions.”

Lurie reiterated that message to families at Sanchez Elementary in the Mission district during the morning drop-off Monday. He said city officials “have your back” and will “look out for you and protect you and keep you safe.”

In Los Angeles, where Trump deployed National Guard troops this summer in response to protests against ICE raids, school officials have taken a more assertive stance to protect families and kids. At the start of the Los Angeles Unified School District school year last week, there were “safe zones” monitored by school police and other officers, while community volunteers served as scouts to alert the district if they spotted ICE activity, the Los Angeles Times reported (opens in new tab).

San Francisco officials say they are taking the threat seriously.

"We are very clear and very aggressive, and have been clear that we don’t need ICE here, and we want kids in schools to be focused on learning,” said state Sen. Scott Wiener, who also appeared at Sanchez Elementary.

The level of anxiety is not the same for all immigrant communities. Within San Francisco’s Chinese immigrant population, for example, fears over Trump’s immigration actions seem more limited, according to Shurrin Zeng, chair of SFUSD’s Asian Parent Advisory Committee and a parent at Balboa High School.

Zeng said there is little talk of ICE raids targeting Chinese students, but tighter immigration polices have had an impact on enrollment, especially in Cantonese-language programs.

“The crackdown does have an impact, though not always directly,” Zeng said. “Immigrants from China are being discouraged or turned away.”

Another parent, Mingzhu Lu, who has a fifth grader at Yick Wo Elementary in Russian Hill, said immigration rarely comes up in conversations in her Chinatown neighborhood.

“Even if someone is undocumented, they won’t reveal their status to you,” Lu said in Cantonese as she dropped her kid off at the school.

Ten minutes before the end of the day at Cesar Chavez Elementary School, a dozen women and a pair of men waited on Folsom Street’s sidewalk, looking into the schoolyard through locked gates. Many in the crowd seemed anxious as they waited for their children to emerge, perhaps sharing a general concern over whether the kids had a good first day. Did they make friends? Were they bullied? Are they safe?

At least a handful of parents also worried about being detained by ICE. Several declined to talk to The Standard, admitting that they were undocumented and afraid.

“It’s a delicate situation for us without papers,” one man said.

Finally, the doors of Cesar Chavez opened, and the parents flooded into the schoolyard. They exited holding hands with their kids, asking questions and listening to stories, mostly in Spanish.

The children, in their floral dresses and Marvel superhero backpacks, babbled loudly, seemingly oblivious to the fears haunting many of their parents.

At 3:25 p.m., the gates closed. The street was quiet and hot, the sun beating down on the suddenly empty sidewalk. No parent nor child had been detained, and fear of ICE had melted away, at least for one day.