For more than a decade, the city of San Francisco wanted to turn the historic Balboa Reservoir (opens in new tab) — long used as a parking lot for City College — into a 1,100-unit housing complex.

It took five years to entitle the project and sell the 17-acre lot to Bridge Housing in 2022. But because of the financing crunch of the past several years, the developer never broke ground.

Then, state money started flowing in, allowing construction to begin this year. One pot of funding came from California’s Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities program, which awarded the developer $45.7 million to help pay for one tower with 159 affordable housing units.

The obscure program has a nice name, but contrary to most other public subsidies, it wasn’t funded by taxpayers. Rather, the money was collected from the state’s biggest polluters.

AHSC is funded through California’s first-in-the-nation cap-and-trade program, which since 2012 has set limits on how much carbon can be emitted into the atmosphere. Future allowances under those “caps” are auctioned off every year to companies. The more a corporation pays, the more it can pollute. Those revenues are collected by the state and routed toward subsidizing public transit, affordable housing development, and renewable energy projects.

Since federal funds for such endeavors are increasingly off the table, developers and transit agencies have become more reliant on cap-and-trade, which has generated some $4 billion annually. But until this week, cap-and-trade was facing dire straits: It was set to expire in 2030, and lawmakers had yet to agree on a framework for an extension.

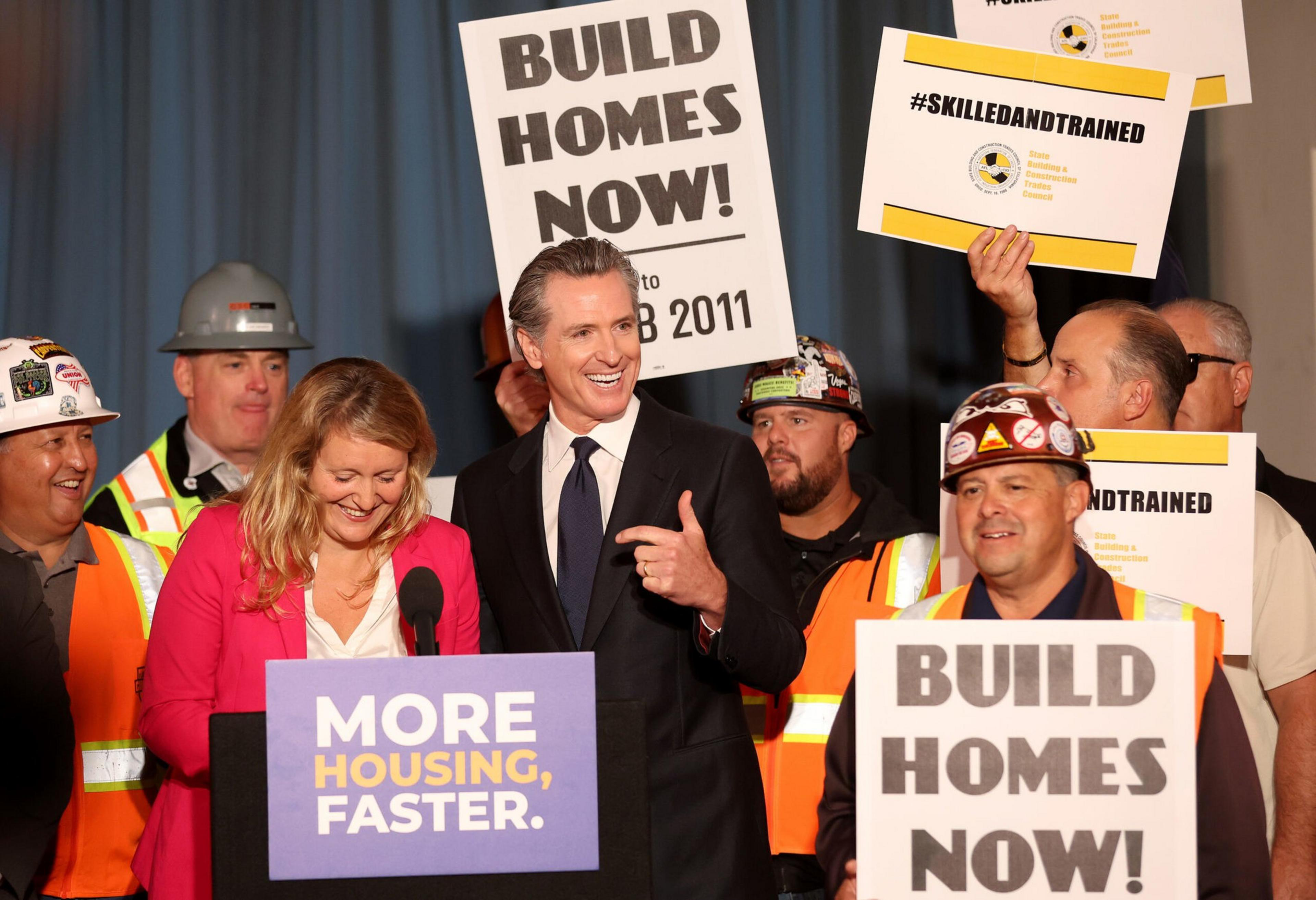

With Gov. Gavin Newsom approaching his final year in office, and without any certainty that the auctions would continue, companies started purchasing fewer polluting credits.

A last-minute, closed-doors deal Wednesday (opens in new tab) between the governor and leaders in the state Assembly and Senate appears to have salvaged cap-and-trade — now renamed “cap-and-invest” — albeit with major changes that would go into effect if the Legislature approves two bills, AB 1207 (opens in new tab) and SB 840 (opens in new tab), on Saturday.

SB 840 is the most consequential of the two, since it proposes reforms to which programs get prioritized and how much funds they receive.

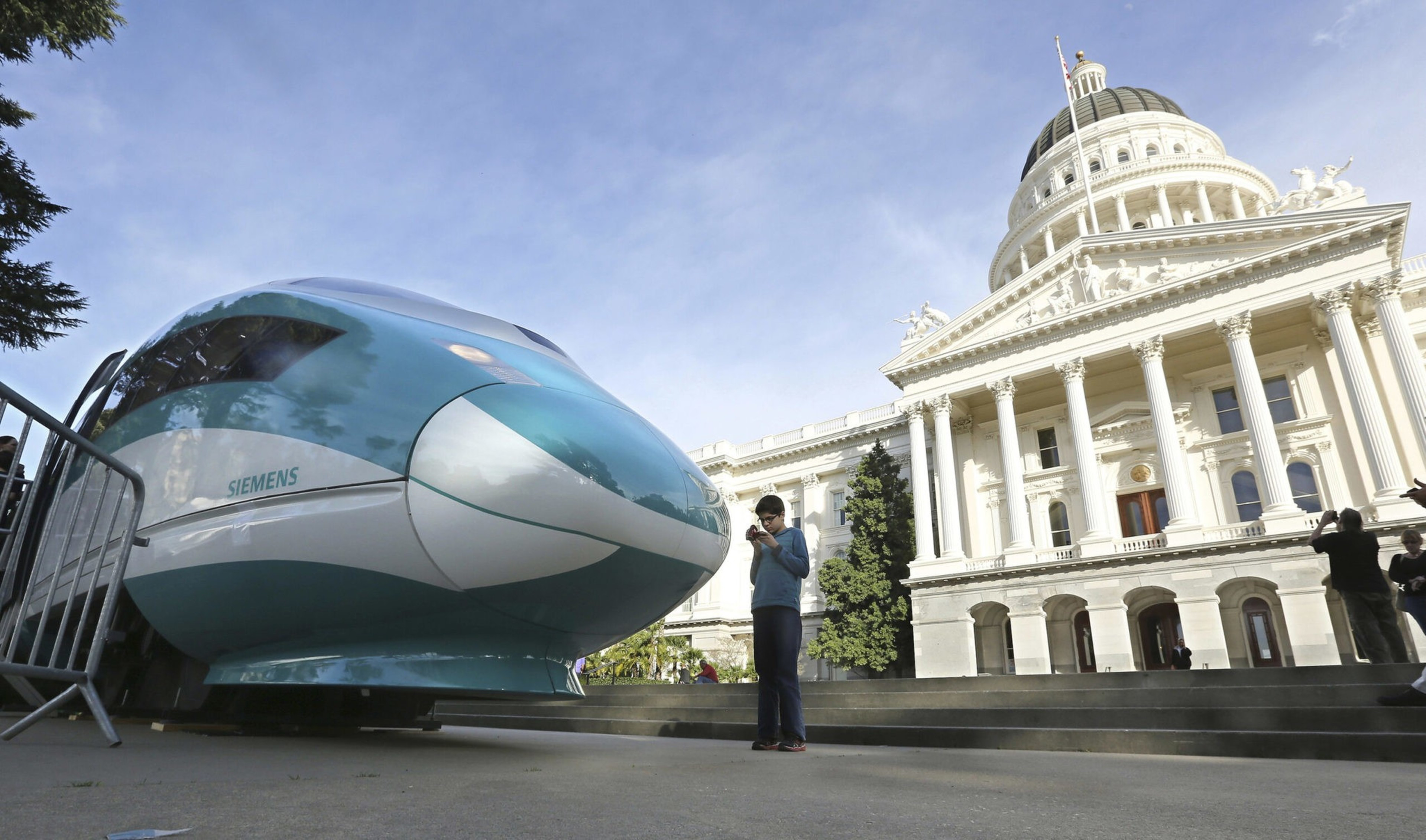

The biggest proposed change is a $1 billion carveout for the state’s much-maligned (opens in new tab), oft-delayed (opens in new tab) high-speed rail project and $1 billion for discretionary spending on issues such as wildfire prevention. The governor’s office insisted on funding guarantees for (opens in new tab) those priorities before revenues can be dispersed to AHSC and other programs.

This could be bad news for San Franciscans, with affordable housing and transit getting the short end of the stick. Previously, those programs received continuous, percentage-based funding that would rise or fall depending on auction revenue. Now, they’re further back in line.

Critics of the new approach say the remaining pot of money might be spread too thin by the time it reaches AHSC, hampering its ability to capture additional revenue if auction proceeds do increase.

Still, this deal was better than nothing at all, said Laura Tolkoff, transportation policy director at the Bay Area urbanist nonprofit SPUR.

“SB 840 goes a long way to provide stable funding for affordable housing and transit,” she said. “It is important to move forward with the reauthorization and have stable funding for the infrastructure California needs to maintain its economic strength and become more affordable, accessible, and climate resilient.”

AB 1207, meanwhile, proposes moving the cap-and-trade program away from state targets and tying the carbon caps to the Environmental Protection Agency’s 2023 guidelines. The authors of the bill say that shift would provide more long-term stability to the auction market.

Should the bills pass, it is expected that the cap-and-trade program will be extended to 2045.

Matt Schwartz, president and CEO of California Housing Partnership, estimates that the AHSC program should get at least $800 million a year under the new deal, an increase from the $545 million it got last year. In a joint study conducted this year with Enterprise Community Partners, CHP estimated that the AHSC program has helped produce more than 20,000 affordable homes in the state. Building housing and improving public transit cuts down on commuting time, thus reducing carbon emissions from cars, the report says.

Since 2014, California’s cap-and-trade program has been linked to a version by the Québec Ministry of Environment. Together, the two form a larger market for multinational companies to bid on.

In the latest quarterly auction (opens in new tab), held last month, the programs sold $51.8 million in allowances for this year and $6.8 million for advance allowances for 2028.

San Francisco and Los Angeles counties have received the most AHSC funding since the program launched. Last year, two affordable housing projects totaling more than 170 units, at 160 Freelon St. and 65 Santos St., received more than $70 million. The year before, three projects in the city were awarded a total of $118.6 million.

The extension of cap-and-trade — even with the new carveouts and caveats — will be welcome news for the city’s affordable housing developers.