“What does it mean if they ask you, ‘Raise your right hand?’” lecturer Curt Neal Sanford asked the class of roughly two dozen middle-aged and elderly Chinese students at City College of San Francisco. More than half immediately raised their hands; the stragglers quickly copied their classmates.

The mood in Sanford’s citizenship test prep class that Wednesday morning was cheerful. After asking the class the meaning of the phrases “sign here” and “wait here,” Sanford led the students in a call-and-response session of what they’ll hear at their naturalization interviews.

“Why are you here?”

Why are you here?

“What is your name?”

What is your name?

“Have you committed a crime?”

Have you committed a crime?

CCSF’s Chinatown citizenship class meets five days a week for a little under two hours. There’s an open enrollment policy, so students are free to show up whenever they can. Each session draws 25 to 30 people. Enrollment is up year after year, but there’s been a particular rush since President Donald Trump’s reelection in November.

Despite the bright, collegiate energy, the stakes are high. Some in Sanford’s class are afraid that, although they are legal residents, their green cards may no longer be enough to keep them in the U.S. They admit that fear, as much as patriotism, has driven them to pursue citizenship.

Joe Wong, a restaurant worker from Guangdong, China, who has had a green card for seven years, sat near the back of the room, occasionally translating for Sanford, who speaks rudimentary Mandarin. (The immigrants in this report are referred to by their preferred, rather than legal, names.) Wong said classmates have told him they want U.S. citizenship because they no longer feel safe. He admitted that he feels the same.

“It’s really scary,” Wong said. “I don’t even want to travel anymore. What if I can’t come back?”

Previously, many Chinese immigrants did not want to naturalize as U.S. citizens because it meant giving up their Chinese passports, as China does not recognize dual citizenship. But with the heightened immigration enforcement under Trump, what once seemed a privileged, safe status now feels precarious. Permanent residents who have been in the U.S. for decades are being deported for years-old misdemeanors.

‘It’s really scary. I don’t even want to travel anymore. What if I can’t come back?’

Chinese American green card holder Joe Wong

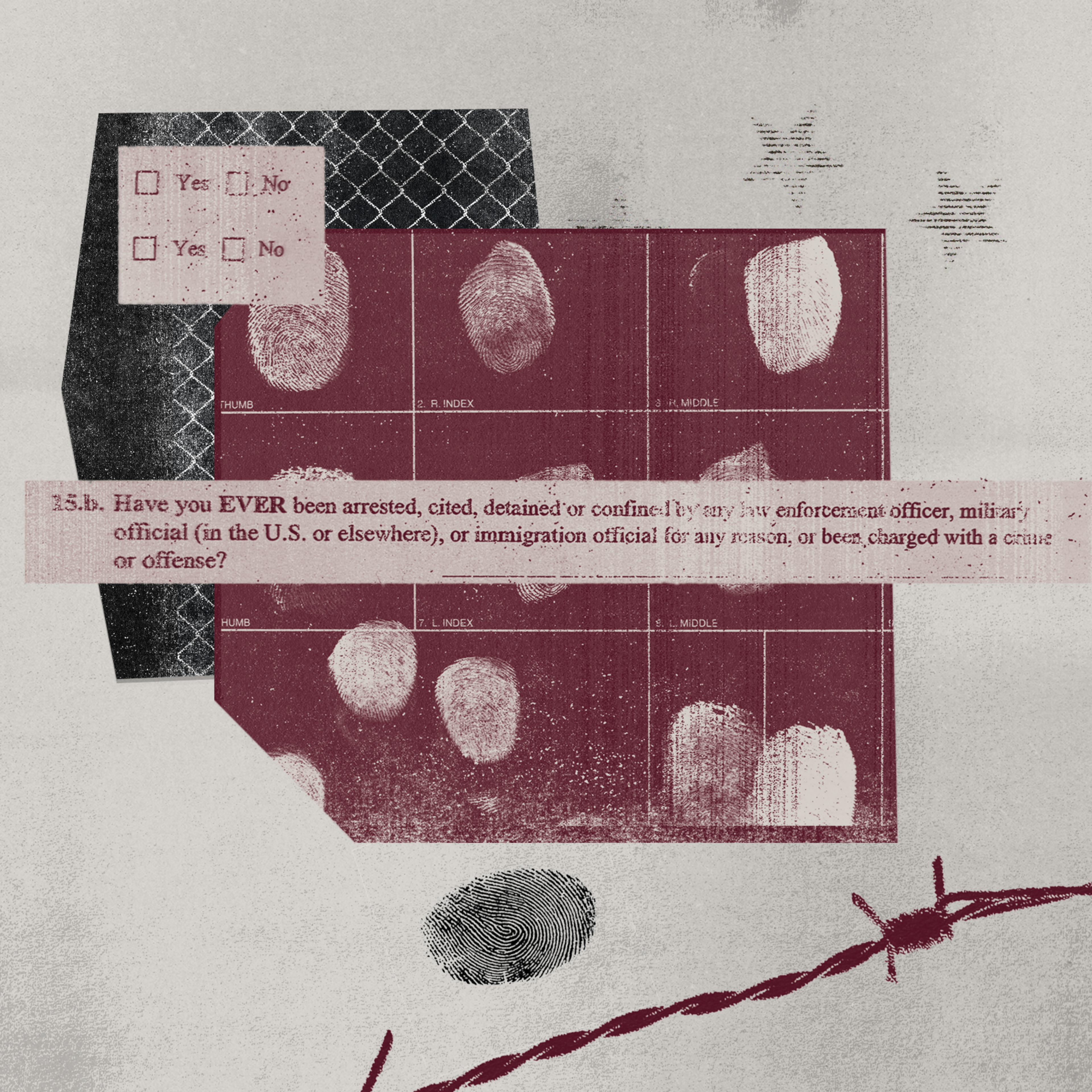

Wong was arrested in 2021 for driving under the influence in San Mateo County. He didn’t crash or hurt anyone, and he didn’t serve time in jail. But misdemeanors, or even incorrectly filed paperwork, are reasons for deportation under Trump. The stories he’s hearing from friends have spooked him: One U.S. permanent resident who was born in China reportedly left for a vacation cruise and wasn’t allowed to reenter the country due to a past DUI conviction.

Wong came to the U.S. seven years ago and attained permanent residency because of his mother’s second marriage to a U.S. citizen. He and his family live in the Sunset. If he were deported or denied reentry to the U.S. and forced to move back to China, he could be separated from his family for years.

Wong said he needs to improve his English to take the naturalization test, which he’s hoping to schedule for next year. Asked a favorite English word he’d learned recently, Wong paused.

“Government,” he said — though it still frightens him.

Such fears are felt widely across the Chinese American community in the U.S., according to advocates. Jose Ng, an immigrant rights program manager at Chinese for Affirmative Action, a San Francisco-based civil rights organization, said community members are increasingly worried about the constant changes to immigration policy, such as the announcement by the Trump administration that the citizenship test may get more difficult (opens in new tab).

Some green card holders are avoiding engaging with the immigration system altogether out of fear, he said. Still, he urges eligible green card holders to pursue citizenship. “Applying for citizenship is the strongest protection,” Ng said. “It means you don’t have to worry about deportation or being barred from reentry.”

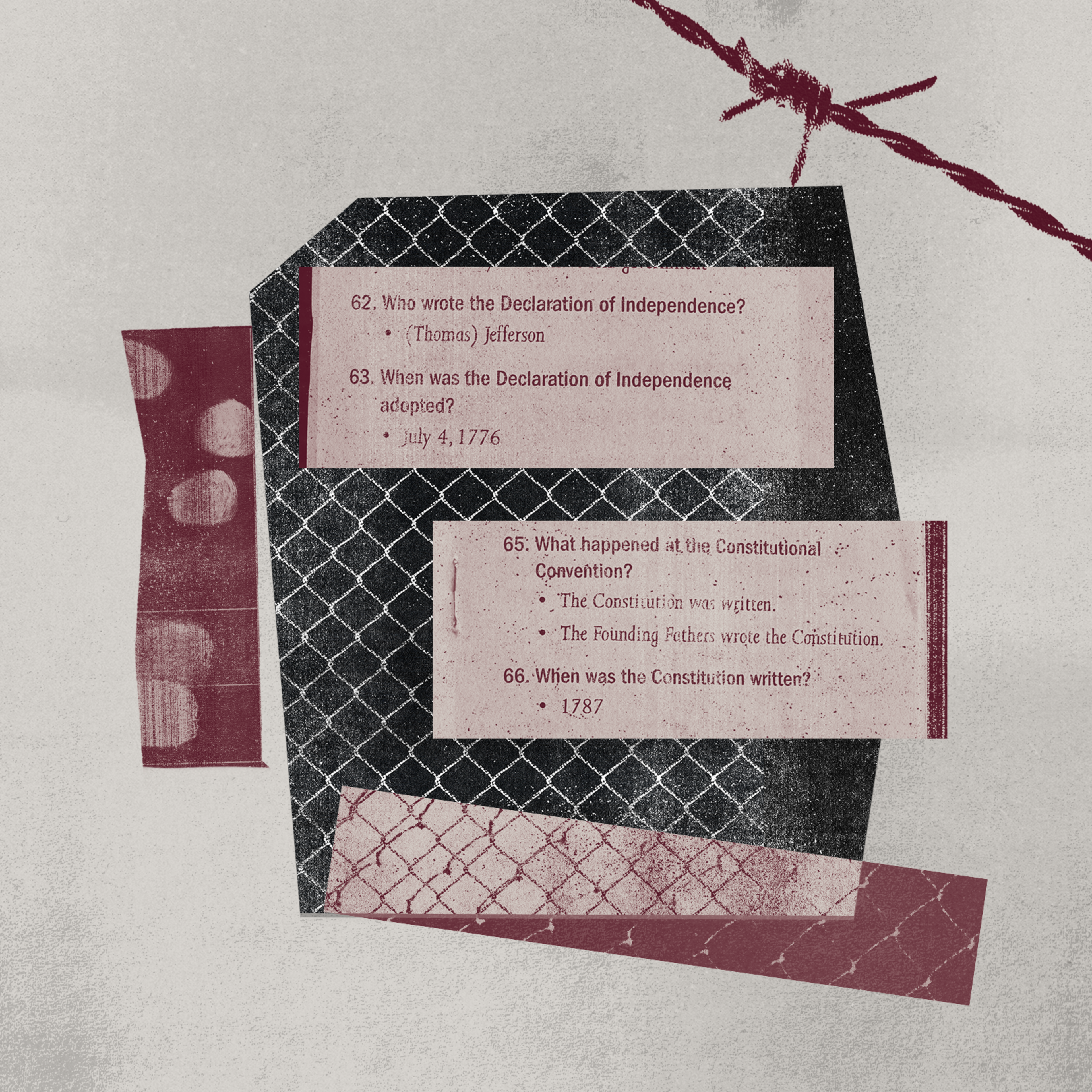

However, immigration laws are extremely complicated. The N-400 form, which prospective citizens must complete, is 20 pages long and accepted only in English. Assistance from a lawyer dramatically increases a permanent resident’s chances of success, but lawyers are expensive. The average cost for an immigration lawyer in San Francisco ranges from $12,000 to $20,000.

San Francisco has a city government agency dedicated to helping permanent residents become citizens: the Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs. It has been inundated with requests for assistance this year. “Immediately after the inauguration of the new president, we saw this kind of increase or uptick in people trying to become citizens,” said Executive Director Jorge Rivas.

The San Francisco Pathways to Citizenship Initiative, a public-private partnership between OCEIA and local foundations that funds community groups helping permanent residents apply for citizenship, has seen demand jump over the last year. Pathways provided screening to 22% more people in the most recent fiscal year than a year earlier and helped 28% more people with naturalization applications.

OCEIA has responded to the heightened demand by successfully fighting to hold onto its budget amid a year of steep city cuts. “An office like ours is very important, particularly in the time that we’re in, to ensure that our immigrant communities feel welcome and feel like they belong in San Francisco,” said Rivas.

On a Saturday morning in September, throngs of prospective U.S. citizens milled about a loud, crowded hall in the San Francisco County Fair Building, waiting for help to become citizens. OCEIA and its Pathways partner organization host this citizen workshop every six weeks. On this day, 120 people were signed up to speak to volunteers who would determine whether they should apply and, if so, help them fill out their N-400s.

Moon Lee, a 50-year-old immigrant from Hong Kong, patiently waited her turn. She received her green card seven years ago but has lived in the U.S. full time for the past five. Under immigration rules, her first two years of legal residency could be seen as “abandonment” and pose a problem in her bid for citizenship.

Lee said she and her family were told during the workshop to delay seeking naturalization, as the rules are tightening and the process feels unpredictable.

“We were advised to wait until Trump was out of office,” she said with a sigh. “But Trump still has three more years left.”

H.Y. Yan, 75, sat nearby and stewed in frustration. His previous application for citizenship was denied in early September, so he had come to the workshop to find out if applying again would be worth the trouble. A monolingual immigrant from Taishan, China, Yan came to the U.S. with his wife through a family reunification visa and has held a green card since 2019.

He said the prior rejection stemmed from an arrest tied to an illegal cannabis operation where he was working — though he insists he did not understand what he was involved in.

“I couldn’t find work at my age. Someone introduced me to a job just watching the door, and they paid me,” he said in Cantonese. “Now they say I have a criminal record, so they won’t approve my application.”

Yan worries the record will jeopardize his future in the U.S., and his only hope would be to seek an expungement. He has asked a lawyer for help.

The San Francisco public defender’s office had a staffed table at the event, advertising its efforts to help aspiring citizens attain “clean slates” by expunging or sealing their criminal records. Hayley Upshaw, who works on immigration issues for the public defender, said the office has seen a surge in requests for expungements since Trump reassumed the presidency.

“People are scared,” Upshaw explained. “So the need for our services has increased among noncitizens.”

The SF public defender is still soliciting those requests, but wait times are getting longer.

Wong, the student from Sanford’s class, showed up to the workshop midway through the morning. He was anxious as he approached the public defender’s table, hoping the lawyers could help him with a past DUI. But they told him they couldn’t do anything — his DUI took place in San Mateo, where they have no authority.

Wong didn’t believe it at first. He protested, saying they weren’t doing their job and had to help him. Eventually, he gave up and walked away from the table, looking ready to cry.

On another Wednesday at his citizenship class in Chinatown, Sanford clicked on a projector and showed his students a video of an actor pretending to be a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services employee administering a naturalization test. The video was shot from a first-person perspective, so the actor looked directly into the camera as she asked, “Why do you want to become a U.S. citizen?”

The class answered with a slew of responses. Sanford suggested a few.

“I like America.”

“I want to vote.”

“I like the freedom.”

The class mimicked each statement in unison.

The video makes the naturalization interview seem easy, with questions anyone can prepare for. But since Trump’s reelection, the path to citizenship has become far less predictable and far more dangerous. Several people have been detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers during or following naturalization exams, for reasons ranging from campus political activism (opens in new tab) to forgetting to file a form with USCIS 10 years earlier (opens in new tab).

This month, an Iranian national was detained (opens in new tab) by ICE in Los Angeles after she’d already passed her citizenship test. She was at her naturalization ceremony, where new citizens are often given little U.S. flags to commemorate a celebratory, patriotic day.

Even if new citizens walk away from USCIS with their freedom and their citizenship, it’s unclear that naturalization is as irrevocable as it seemed to be last year. A June memo from the Department of Justice listed denaturalization as a priority. Trump has even threatened to take citizenship away from vocal critics like Rosie O’Donnell, who was born in the U.S.

Sanford drew a diagram on a whiteboard outlining the three branches of the federal government. As he explained why certain states have more congresspeople than others, Bell Chen, 26, an immigrant from Guangxi, China, scratched his head in confusion.

Like Wong, Chen is a restaurant worker living in the Sunset. He’s had his green card for six years. He likes Trump and thinks the administration’s mass deportation efforts are a good thing, even if they might affect him.

“I think if I just spend some time memorizing the answers, it should be fine for me,” Chen said in Mandarin. “I just need to work hard.”

He was confident he would get the answers, eventually. Whether that would be enough to make him a citizen is anyone’s guess.