When De’Mario Grant became a security guard at the de Young Museum in 2010, he thought he’d landed his dream job — following in the footsteps of his grandfather, who once held the same post. By 2015, he’d risen from temp to acting supervisor. But as his responsibilities grew, he said, so did requests for overtime work. The 16-hour shifts on his feet in a suit and dress shoes were difficult, he recalled, and his chronic back pain worsened.

One night, he pulled open a heavy steel door to the security control room and doubled over in pain. What had started as strained muscles deteriorated to pinched nerves and spinal deformities, according to his doctor, leaving him unable to stand or lift without agony.

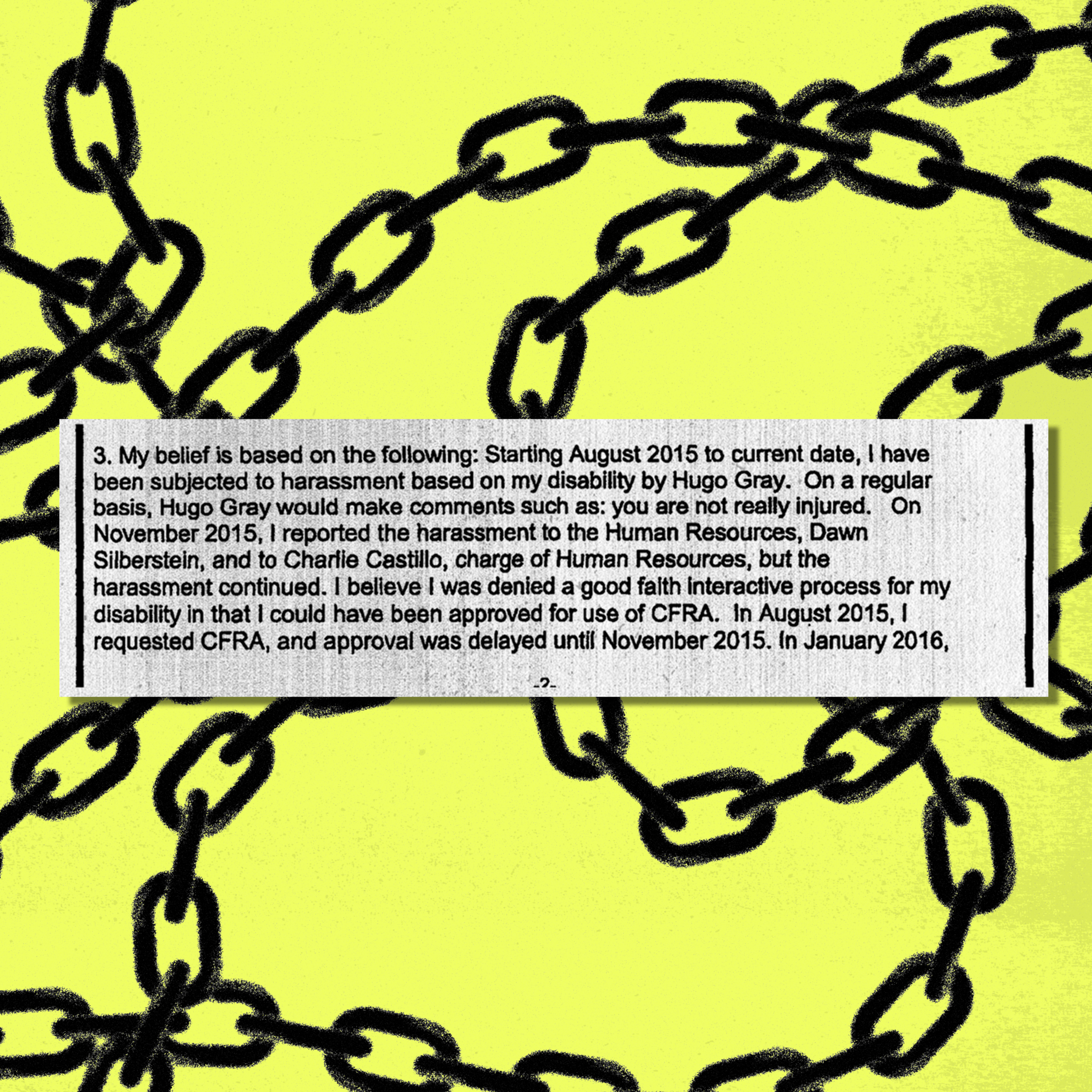

The occasional sick day turned into requests for extended leave, which were allegedly denied by managers and HR. Grant says they doubted his disability and demanded excessive paperwork.

“It just felt like I was in a bad dream,” he said. “I have a documented medical injury. The doctor is writing me tons and tons of notes, and then to hear from colleagues that management was gossiping about it and HR has now villainized me? It wasn’t just surreal but embarrassing.”

Grant sued the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the city, which operates the De Young and Legion of Honor, in 2017, alleging harassment and retaliation, and won a $285,000 settlement two years later. But he alleges management continued to scrutinize his requests for medical leave until June 2025, when he was terminated.

Grant provided The Standard with paperwork indicating he plans to file another lawsuit against the Fine Arts Museums, alleging wrongful termination and whistleblower retaliation.

He’s not the only one. Records obtained from the city attorney’s office show that, since 2016, at least nine current and former security guards and a cashier have sued the Fine Arts Museums, alleging a decade-long pattern of discrimination, harassment, and retaliation based on age, race, and physical and mental disability by the museum’s security management team and human resources staff. The city has doled out more than $1 million across seven settlements.

The suits claim that managers and colleagues threatened violence, engaged in stalking, hurled racist remarks, and made subordinates perform menial tasks under threat of getting fired.

The most recent lawsuit was filed in July by Mohammad Joiyah, a former museum guard at the de Young. It was his second lawsuit against the Fine Arts Museums (the first was settled in 2021 for $200,000 (opens in new tab)), this time alleging disability discrimination, religious and racial harassment, failure to accommodate, retaliation (under both state medical law and whistleblower law), and wrongful termination.

Joiyah alleges that managers in the security department targeted him for being Muslim and for being physically and mentally disabled. (He alleges the disabilities stemmed from workplace injuries and harassment.) Managers allegedly called him a “terrorist,” and Ramiro Rodriguez, the manager of museum security, allegedly threatened to “go home, bring a gun and shoot” him, according to the lawsuit. Joiyah worked at the de Young for 15 years until he was fired abruptly in January — one day after submitting a request for medical accommodation.

A representative of the Fine Arts Museums said, “Mohammad Joiyah was terminated with just cause.” Rodriguez did not respond to requests for comment.

In lawsuits and interviews, current and former security guards allege a pattern of ongoing abuse by museum management that the workers’ union, SEIU 1021, hasn’t advocated to resolve. This is in part because of an alleged conflict of interest: The union represents six of the department’s nine managers.

Additionally, the union and workers said attempts to reach agreements on policies that ensure workplace safety for museum guards have been continually delayed by the museum.

Lawsuits and interviews paint a picture of guards getting injured on the job due to an alleged lack of safety mechanisms, like adequate seating, and denied medical leaves. Security guards allege they are routinely coerced into attending meetings without representation from the union or HR and that management has made threats in the presence of union representatives that have gone unpunished.

“There’s no oversight, nobody holding the people in our department accountable,” said Kellan Dunn, a security guard at the de Young who, in 2020, received a $183,000 settlement in a discrimination and harassment case against the Fine Arts Museums. “It’s almost like this department is willing to work you till you die and then replace you for somebody because they’re not going to have to pay them as much.”

An investigation by The Standard reveals that behind the Fine Arts Museums’ exhibitions and record-setting galas (opens in new tab) is a decade-long pattern of alleged abuse and mismanagement that continues within the museum’s largest and most invisible department, security.

The Standard spoke with more than a dozen current and former workers and security guards for the Fine Arts Museums, several of whom declined to speak on the record, citing their intention to sue, fear of losing their job, or physical or emotional threats from coworkers. Security guards said supervisors who are named in the lawsuits instructed staff not to participate in The Standard’s investigation or they could be disciplined.

A representative of the Fine Arts Museums said the cluster of lawsuits filed by security guards concern events primarily from 2014 to 2016 and emphasized that leadership has changed since then. The representative added that today’s management is diligent about strictly following employment rules to avoid disputes and potential settlements, stressing that procedures are handled “by the book.”

Seven of the nine lawsuits, however, allege troubling workplace behavior after 2016, and interviews with current and recently former staff indicate much of it is ongoing.

“The security department at the Fine Arts Museums is notoriously terrible,” asserted Joan Herrington, a retired Oakland employee attorney who has represented four current and former employees in lawsuits against the institution. “This is probably the worst employer I’ve ever encountered in my experience.”

Inside the security ranks

The Fine Arts Museums are the city’s largest public arts institution and among the most visited museums in the U.S. They are run through a public-private partnership. The city owns the buildings that house the de Young and the Legion of Honor, as well as the land and a majority of the collection of art and artifacts. The city contributes roughly 25% of the museum’s annual budget and is responsible for hiring security personnel. Meanwhile, the nonprofit Corporation of the Fine Arts Museums operates the museums, handling exhibitions, programs, and curatorial operations.

Compared with the rest of the museum staff, security guards are disproportionately people of color. They guard a 150,000-object collection that is the envy of cities worldwide.

The security department employs 137 full-time and part-time staffers, nearly eight times as many as the second-largest department, according to a budget (opens in new tab) submitted to the Mayor’s office in March.

In Joiyah’s July lawsuit, he alleges that his requests for medical accommodation were mocked by management and denied by human resources. He says that when accommodations were granted, they were often rescinded. One day after submitting a letter from a doctor “providing medical restrictions” on when he could work and how much he could lift, Joiyah was allegedly terminated with no notice.

Joiyah claims in his lawsuits to have physical and mental disabilities that stem from workplace accidents and continued harassment by coworkers and superiors. In addition to carpal tunnel syndrome, muscle spasms, major depressive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder — which he claims have been substantiated by medical documents — Joiyah says he was twice injured on the job. In 2013, a fall caused a spinal injury, and in 2021, he collided with an airflow blower at the de Young’s gift shop, resulting in a traumatic brain injury and post-concussion syndrome, according to the suit.

In one instance, he alleges, he was humiliated when a mobility walker was placed in the lost and found with a sign taped to it stating, “For use of Joiyah ONLY.”

His allegations of racial discrimination carry back to his first lawsuit, in which he accused a coworker of repeatedly calling him a terrorist, threatening him with violence, and hurling accusations that he was “stealing money away from disability and feeding your wife and children.” That coworker does not appear to have worked for the museum since 2021, when the suit was settled.

Joiyah also alleges that his supervisor, Patrick Smithwick, called him a “terrorist” in front of other employees. In fact, Smithwick himself in 2002 was criminally charged with illegally possessing explosives and making or transporting a destructive device, according to documents seen by The Standard. The felony charge was dismissed, and Smithwick was sentenced to community service and paid a small fine for the misdemeanor. The case was expunged in 2005.

Smithwick’s actions as supervisor have stirred controversy both in and outside of the museum.

In 2013, his private security company, Smithwick Executive Protection Patrol, was fined $16,115 for four violations of federal law under “employment-related offenses.” Details on the offenses were not immediately available.

On the afternoon of Oct. 29, 2023, a man rushed to a de Young security guard requesting access to the museum’s private defibrillator for use on Gary Hobish (opens in new tab), a man who was in cardiac arrest outside of the museum. According to security guards, there was no acting supervisor at the time. Smithwick, who was acting supervisor at the sister museum the Legion of Honor, was contacted and allegedly directed the de Young’s guards not to lend out the defibrillator, citing museum policy and concern over having the device stolen. Paramedics eventually arrived, but Hobish died (opens in new tab), leading to a contentious debate over the obligations of museum staff. Smithwick’s involvement in the incident has not been revealed until now.

At the time, a museum spokesperson denied to the San Francisco Chronicle that a supervisor declined to loan out the defibrillator. The Standard spoke to four security guards who said he did, and, according to emails obtained by The Standard, additional defibrillators were added to the museum grounds after the incident, and the policy was adjusted to allow guards to loan out medical equipment in case of emergency.

“It’s a horrible thing to have someone die because of insecurity within the staff here,” said Chris Kirby, a security guard who has worked at the Fine Arts Museums for more than 20 years and was on duty that day. “Even if you lose a defibrillator, it seemed like a legitimate need, and I think it should have been passed out.”

Smithwick did not respond to requests for comment on that incident, his criminal record, his company’s violation, or the allegations of his behavior detailed in the lawsuits.

Joiyah declined to comment on the lawsuit. His case is scheduled for a hearing in December.

A concerning pattern

The delays and discrimination described by Grant and Joiyah appear almost verbatim across the other lawsuits. They include allegations that managers doubted physical and mental disabilities in front of guests and colleagues, denied medical leave requests despite legal paperwork from physicians, and took punitive disciplinary measures that plaintiffs allege followed soon after requesting accommodations or filing whistleblower complaints.

In a 2019 lawsuit against the city, de Young security guard James Flowers alleges that after he reported a colleague for threatening behavior, management retaliated by changing his job conditions and forcing him to work alongside that colleague. Across multiple lawsuits, guards allege they faced retaliation such as being placed on unpaid leave or suspensions for filing for medical leave or receiving low scores on performance evaluations.

Several of the lawsuits describe misconduct by Tabari Shannon, the director of security, and Hugo Gray, the associate director of security.

Shannon and Gray did not respond to requests for comment.

Shortly after Joiyah’s second workplace injury, which required disability leave and ongoing medical treatment, he alleges that Shannon began retaliating for his workers’ compensation claim, issuing a 33-day suspension.

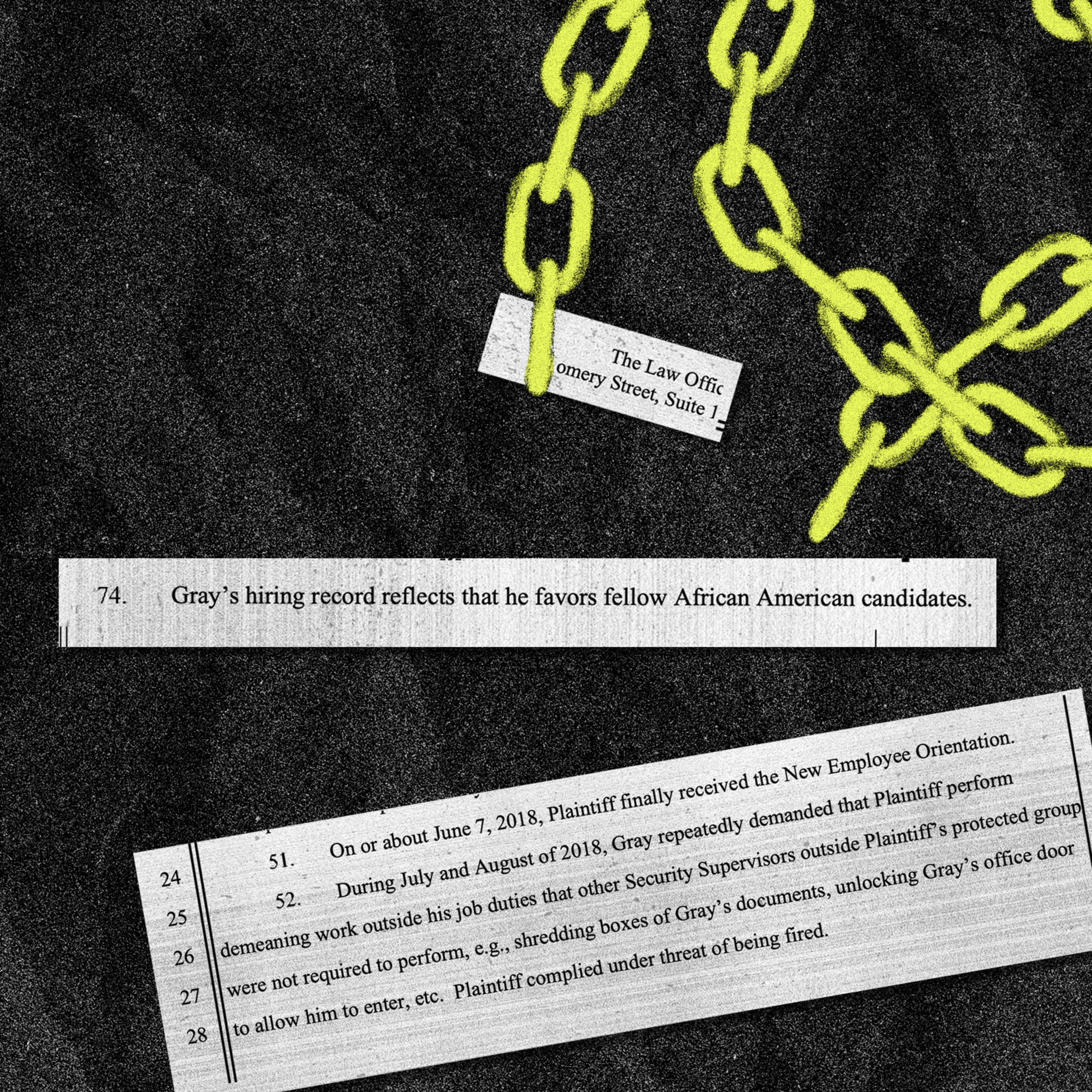

A 2021 lawsuit filed by former museum guard Rick Lam alleges that Gray once said in front of a union representative, “I don’t have any problem putting my foot on people’s necks when I want something done.”

Lam, who is Chinese, alleged in his suit that he was reprimanded and denied a promotion by Gray, who is African American, based on his race. The suit described the supervisor as a “self-declared” bully who turned Lam into his personal servant, demanding he shred Gray’s personal documents and open the door to his office on command, under threat of getting fired. It further alleged that Gray favored hiring African American candidates.

The city settled Lam’s lawsuit in December and awarded him $350,000 (opens in new tab) — the highest sum paid among the suits against the Fine Arts Museums that The Standard could verify. “Set up to fail,” was how Lam described his hostile treatment by Gray.

Dunn, the de Young security guard who received a $183,000 settlement from the city in 2020, alleged that Gray denied believing he had a disability and taunted him for needing medical leave, while also restricting the basis on which he could take leave. Gray also allegedly said, referring to himself, that he was “from the hood” — a statement Dunn perceived as a violent threat.

In 2000, Gray pled guilty to driving while having .08 or higher blood alcohol, according to the Contra Costa County district attorney’s office. He was sentenced to 10 days in county jail, three years court probation, and other standard terms and conditions.

According to the Bureau of Security and Investigative Services, Gray’s security license expired in 2007, a year before he was hired at the Fine Arts Museums. California law does not require city institutions to require their guards to have licenses.

The City’s Human Resources Department did not provide a statement on guard license and criminal records by the time of this story’s publication.

Dunn said that, like Grant, regularly working double shifts exacerbated his spine injury.

Prior to their lawsuits, former city human resources director Micki Callahan issued official determinations that Dunn and Grant’s medical leave rights had been violated — a finding that, according to Dunn’s lawsuit, placed responsibility on the museums and Gray.

“It was a great job at one point,” said Dunn. He said the security department has been in a “downward spiral” for the last decade and alleged corruption and abuse from management and HR.

Along with Gray and Shannon, Charlie Castillo, the former head of human resources at the Fine Arts Museums, who now works as an administrator at BART, is named in several lawsuits as consistently stymying requests for medical leave. He declined to comment.

In a whistleblower complaint detailed in his July lawsuit, Joiyah alleges that Shannon, the director of security, spent work time watching movies and sleeping while on the clock and that Gray came to work intoxicated and left early to meet his girlfriend, who also worked in the department.

Despite the alleged harassment and large sums being paid out by the city, Gray, Shannon, Rodriguez (the guard who allegedly threatened to shoot Joiyah), and Smithwick are still employed by the Fine Arts Museums.

A ‘useless’ union

Current and former security guards describe the union, SEIU 1021, as “useless” when it comes to advocating on their behalf.

Although the union does not represent Gray, Shannon, and Rodriguez — the top three security managers — it does represent the six security supervisors, including Smithwick. Several workers said this relationship creates a conflict of interest when it comes to mediating conflicts and achieving milestones in battles for workplace rights. Because the guards are employed by the city, California law allows them to be represented by the same union as their subordinates, whereas the National Labor Relations Act prohibits this type of representation.

Jennie Smith-Camejo, a spokesperson for SEIU 1021, said stewards are assigned to members in a way that aims to avoid conflicts of interest.

“We represent many supervisors and line workers across city departments very successfully,” she said. “We believe representing more workers builds more solidarity and unity and outweighs the perceived conflicts and divisions by ranks.”

In a collective bargaining agreement (opens in new tab) published in July 2022, the Fine Arts Museums agreed to meet with the union to discuss options for adding gallery seating for the guards by Jan. 1, 2023.

According to the museum and union, chairs for security guards weren’t installed until November 2024, though some guards said they didn’t see them until January 2025.

“This happens all the time with contracts. We get something negotiated; the city drags its feet,” Smith-Camejo said. “We are not the ones responsible for buying these fucking chairs.”

Smith-Camejo did not address requests for comment on the volume or severity of complaints from security guards employed by the Fine Arts Museums.

Across the suits, plaintiffs said the actions of their managers caused them to lose promotions, overtime opportunities, and, in some cases, their jobs. Several plaintiffs said the treatment caused medical distress and financial instability. Grant, Dunn, Joiyah, and others who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation said the abuse is even more widespread across the department.

“I would say a good 90% to 95% of the staff there just keeps quiet and they don’t say anything,” Grant said. “That isn’t my personality. Whether they are in my favor or in management’s favor, the rules are the rules, and they’re there for a reason.”