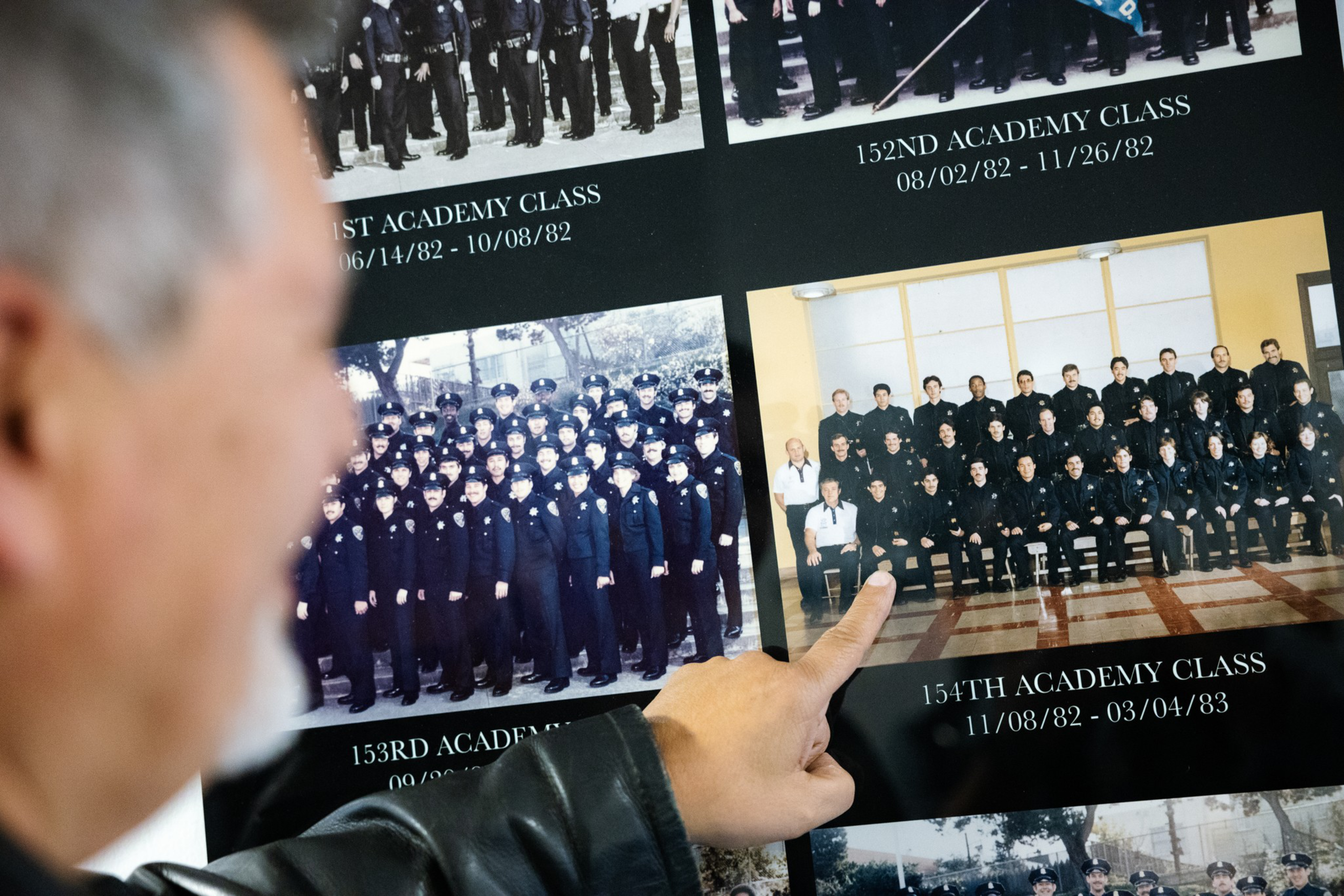

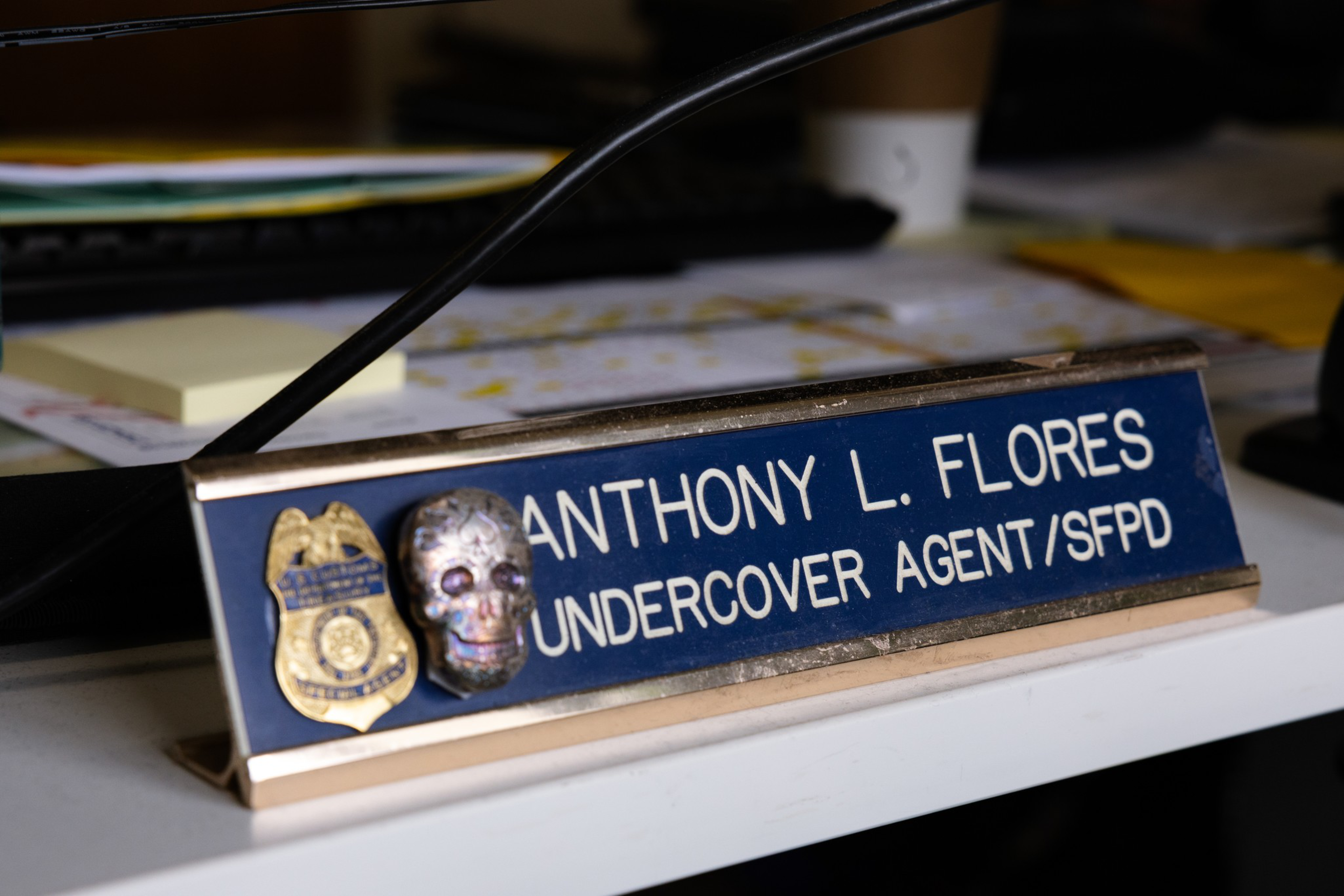

After 43 years of service, Inspector Antonio Flores is the San Francisco Police Department’s longest standing detective. He’s been a cop for so long his title retired before he did — inspectors are now called sergeants. And many of the cases he’s solved weren’t even considered crimes when he was first handed his badge.

When Flores enrolled in the San Francisco police academy in 1982, the term “domestic violence” hadn’t reached the mainstream. So-called “wife beaters” were rarely held accountable, and calls for help from “battered women” were largely ignored. It was legal to rape your wife in California until just a few years prior.

But a set of grim statistics pushed San Francisco to stop ignoring crimes in the home. A 1994 study by the city’s Commission on the Status of Women found that 38% of homicides were domestic violence, and nearly 2 out of 3 women killed in San Francisco were victims of an intimate partner.

In 1995, the SFPD announced the formation of a domestic violence unit with six detectives; the thinking was that if police took domestic violence crimes seriously from the start, they could lower the murder rate. Shortly after his promotion to inspector, Flores was told he would be transferred to the new unit.

He thought it was a punishment.

“I go, ‘What did I do wrong? I don’t want to go there,’’” Flores recalled. “I lived that my whole life. I got away from that stuff.”

Flores, a San Francisco native, said his late father abused his mother physically and emotionally throughout his childhood. She left when he was 22 — the year he joined the police force. Later, Flores asked why she’d waited so long. “You’re safe now,” she told him.

Flores’ new assignment wasn’t a punishment — the unit needed someone who spoke Spanish. And it turned out he was good with victims. “It was like a fish to water,” he said.

By the late 1990s, the unit — the first of its kind in Northern California and only the second in the state — had expanded to 20 investigators, the district attorney’s office had opened a domestic violence unit, and the Hall of Justice had a courtroom dedicated to domestic violence cases.

The plan worked. The city went 44 months without a single (opens in new tab) death related to domestic violence, between 2010 and 2014, a period that coincided with the formation of the Special Victims Unit in 2011. Flores is now acting lieutenant of the SVU, which investigates domestic violence, sexual assault, child abuse, human trafficking, elder abuse, stalking, and internet crimes against children.

But over the past six years, its workforce has plummeted.

In 2019, the SVU had a staff of 72 — 65 sworn officers and seven civilian employees. Now, it is down to 43 — 35 officers and eight civilians — the lowest staffing level in the unit’s history.

The SFPD, like other major U.S. police departments, has faced a staffing shortage in recent years. But the SVU has shrunk at more than twice the pace of the department overall. Over the past six years, the SFPD’s contingent of sworn officers dropped 20%, while the SVU is down 46%.

The core investigative staff — sergeants and inspectors who work cases — is down 52%, from 60 to 29.

The number of crimes the SVU handles has remained steady, but fewer make it through the system. From 2016 to 2023, the SFPD passed 39% fewer domestic violence and rape cases to the district attorney’s office. Those numbers recovered somewhat in 2024, but the unit still referred 502 fewer such cases that year than it did in 2016.

Interviews with law enforcement, victim advocates, and community agencies that work closely with the SVU speculate as to why the unit’s ranks are suffering: it might be shifting fiscal priorities, a lack of seasoned officers able to handle the nuanced work, or simply an exceptionally high rate of burnout.

“Think about seeing child porn for several years,” Flores said. “At some point you go, ‘I need a timeout.’”

In a department that struggles with attrition, Flores is an anomaly. He’s been a cop longer than many recruits have been alive. Suspects he arrested decades ago have turned their lives around and become his friends. He’s watched his unit flourish. He knows what a staffed-up SVU is capable of, and who pays the price when it’s slowly chipped away instead.

The Board of Supervisors’ Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee gathered in May in City Hall for what looked, at first, like any other hearing. After routine agenda items — liquor license transfers, contract negotiations — Supervisor Myrna Melgar took the microphone to introduce the day’s main topic: the SVU’s staffing crisis.

“The overarching storyline in my childhood was domestic violence in my home,” Melgar began. When the SVU is stretched thin, she said, “we’re making a choice and a trade-off at the expense of the most vulnerable people in our society.”

What followed broke from the usual bureaucratic script. One after another, high-ranking city officials, members of law enforcement, and survivors spoke with rare frankness, sharing — at times between voice-cracking sobs — harrowing accounts of domestic violence and sexual assault. The human toll of an understaffed SVU wasn’t just a number on a chart — it was there, in the room.

‘Think about seeing child porn for several years. At some point you go, “I need a timeout.”’

Dan Silver, the SVU’s acting captain, explained that without enough officers, the unit is forced to triage, placing cases in a “pending folder” until a detective is available. The number of pending cases varies; there were 15 at the time of the hearing.

The lack of follow-up can mean evidence is lost or suspects flee. For victims, it can create a perception that what happened to them doesn’t matter to law enforcement.

The SFPD’s 128 investigators are spread across five units, each with their own caseloads and challenges. SVU investigators handle an average of 110 cases per year, which puts them in the middle of the pack. But those cases are often complex, sensitive, and have high stakes.

Staffing decisions are determined by the acting captain and the chief. In 2023, a city-commissioned SFPD report (opens in new tab) recommended that the SVU have 50 investigators — 21 more than the current total.

“In a perfect world, the number would be greater, but we’re not in a perfect world,” Deputy Chief of Investigations Rachel Moran said at the hearing.

Then Moran, a 30-year SFPD veteran, looked directly at the supervisors. “As a survivor of sexual assault and domestic violence, it’s very important,” she said. Her voice cracked, and she choked back tears as she continued. “So we recognize that, but we also have to have a commitment overall to the bureau — to the city.”

Moran covered the microphone with her hand and took a breath.

“I get it, deputy chief,” said Melgar. “I get it.”

As for how many officers the SVU needs?

“ The answer is whatever we can get,” said Moran. Retired officers, civilians — the situation is so dire, the SVU would take anyone willing.

In the public comment period, Paméla Michelle Tate, executive director of Black Women Revolt Against Domestic Violence, expressed her support for the SVU but described the risks of relying on an understaffed, undertrained force. Others recounted horror stories: officers dismissing victims’ injuries, victims arrested after calling 911. One woman said that when she called police about her neighbor repeatedly exposing himself to her children, an SVU officer brushed her off, telling her, “A man’s home is his castle.”

Tate described two recent clients who called police after being strangled by their partners. Both were dismissed by patrol officers who couldn’t immediately see bruises, which can show up later on dark skin. Women of color are the victims in a majority of the crimes the SVU investigates.

“ These are not things that I hear regularly,” Tate said, “but once is enough for someone to become deceased.”

Flores and fellow SVU veteran Inspector John Keane, the SVU’s stalking expert, came up repeatedly at the May hearing as the type of cops the city needs and is lucky to have, even in short supply. Those who understand the stakes.

“I get it,” Flores said. “Some people get it; some people don’t get it.”

He understands why victims stay in abusive relationships, why they might be frustrated with law enforcement, and why the work requires both patience and urgency. That has made him popular among victim advocates.

“Tony’s kind of a little patch of light,” said Beverly Upton, executive director of the San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium, who has worked hand-in-hand with Flores for 25 years. “He’s one of the good guys. He has a great heart, and he’s saved lots of lives.”

When Flores earned Officer of the Month (opens in new tab) in January, SVU Captain Alexa O’Brien noted his investigative chops, calling him “the backbone of a critical unit” whose “expertise has made him the department’s go-to authority.”

But “getting it” doesn’t make the work any easier.

Flores’s office is on the fifth floor of the granite-clad Hall of Justice, one of San Francisco’s most depressing buildings. “Dirty Harry” was filmed there, back when the elevators still worked. They were supposed to be replaced last year but often remain out of commission, forcing crowds into eerie stairwells lined with asbestos. The SFPD moved most of its headquarters to a gleaming Mission Bay facility in 2015, but the investigators were left behind. The hall’s modern austerity seems a fitting place for the department’s toughest and often most hopeless police work.

One morning in late August, Flores pointed to a towering stack of paperwork on his desk. “ Half of that pile is what I did yesterday,” he said.

Behind mesh-covered glass doors stamped with the SFPD logo, there’s an eerie quiet. Desks sit empty. Hallways echo. “There used to be 20 people over there,” he said, pointing to the vacant desks in the office next door. In the late 1990s, 20 detectives investigated domestic violence exclusively. Today, 17 handle domestic violence, as well as child abuse, sexual assault, and elder abuse; the 12 others handle the rest of the unit’s cases.

Flores now runs the unit’s human trafficking team, training four sergeants to tackle some of the city’s most difficult cases, but he still regularly picks up domestic violence cases “to stay sharp.” He enjoys the freedom that comes to seasoned detectives after decades of grunt work. “I joke with my bosses, ‘What are you gonna do — send me to the SVU?’”

Since 2018, San Francisco police have logged around 16,000 domestic violence incidents. At two-thirds of the addresses where officers responded, they returned two or more times. More than a quarter of locations had five or more incidents. At around 350 homes, police responded 10 or more times. At one address, there were 106 incidents.

For Flores, fewer hands just means more work.

“The impact is you’re moving at a fast pace,” he said, even when a case requires more than he has to give.

For now, the Band-Aid solution is overtime — costly and unsustainable, contributing to investigator burnout and diverting funds from an already strapped city budget. Flores’ overtime pay has more than doubled over the past decade, peaking at more than $160,000 in the last fiscal year, which still doesn’t put him in the top 200 of overtime-earning SFPD officers.

The walls in his office are covered with memorabilia from a storied career: a precinct map of San Francisco from 1972, outdated arrest cards, old crime bulletins, and a photo of his police academy class from 1983. A closet holds uniforms and suits for court appearances. Day to day, he dresses casually. “You want people to relax when you‘re trying to get the whole story from them,” he said.

The SVU investigates crimes in which victims tend to feel enormous shame. Justice is usually possible only for a victim who cooperates with law enforcement — but building the trust that requires takes time and patience, which is only more difficult for a short-staffed unit.

When someone calls 911 or visits a precinct to make a report, it’s generally not Flores who responds but a patrol officer, the first available. The initial contact with an officer “can really make or break how that victim is gonna go through the process,” said Flores. “If you have a bad contact with law enforcement, that sticks with you forever.”

A 2004 Supreme Court ruling raised the stakes of those first moments between victims and patrol officers. In Crawford v. Washington, the court ruled that only statements made spontaneously — not in response to questioning — could be used in court. This means that what a victim blurts out in the chaos of the scene, often caught on body cameras, might be the only evidence prosecutors can use if the victim later backs out of cooperating with an investigation.

Flores teaches the state-mandated domestic violence training to patrol officers. “ I tell ‘em to slow it down. Let them tell you what it is, as long as they’re not killing each other,” he said. “If they’re screaming, yelling at each other, saying, ‘Hey, he did this thing, did that, no, I didn’t touch her,’ just let that thing go before you intervene.”

California’s mandated training warns that domestic violence calls are the most dangerous for officers, resulting in the most injuries and deaths. These can be some of the most high-stakes moments of an officer’s career. Everything they do and say in the middle of attempting to calm the chaos can dictate how a case plays out, and whether it makes it to court.

The reality of that burden plays out in the Hall of Justice, where domestic violence trials have become increasingly rare.

The path to justice in crimes the SVU investigates looks like a steep funnel. In 2023, the city’s 911 dispatch logged more than 6,500 calls related to domestic violence and stalking. The short-staffed SFPD responded to about half the calls, and half of those — 1,600 incidents — resulted in an arrest.

When SVU officers are handed a case, they need to quickly and sensitively build trust with the victim and gather enough evidence to take it to court. But when they can’t keep up with the caseload because of short staffing, cases linger, victims back out, and opportunities for justice dwindle.

Staffing at the DA’s domestic violence unit slightly increased this year, according to the office. It currently has 12 prosecutors and one managing attorney. But the impact of an undermanned SVU is clear from the court docket.

In 2019, when the SVU peaked at 65 sworn officers, 36 domestic violence cases went to trial, with 32 resulting in convictions. By 2022, just four cases reached trial, with one conviction. Roughly 1,100 domestic violence cases were referred to the DA’s office in 2023. Fewer than half were prosecuted; the rest were dismissed, often due to lack of evidence. Only 14 cases went to jury trial, and four ended in convictions.

During closing arguments in one trial this summer, the prosecutor faced the jury and clicked through slides on a flatscreen. The defendant was arrested in October 2024 after he allegedly dragged his then-girlfriend into her apartment, punched and strangled her, then stole her phone and laptop.

The DA paused on a close‑up of a woman’s neck. Twelve San Franciscans looked at the screen, trying to determine if she had, in fact, been strangled. One juror stood, walked closer, and squinted. The paramedic had testified that the redness could be psoriasis. Who were they to believe?

The high‑ceilinged, fluorescent-lit room held close to a hundred seats in the gallery, but only three people watched. The accused sat beside his public defender, yawning, stretching, sipping what looked like an iced coffee.

In her closing argument, the DA reminded jurors that it wasn’t the victim who called 911 — it was a neighbor who’d found her in tears. Perhaps the fact that someone else stepped in to call for help would make her story more believable.

For Flores, trials represent the ultimate test of his work. “I love jury trials. I call ‘em the Super Bowl,” he said. But making it to the playoffs requires time and patience. “ I’ve had cases where it took almost six years to get to a jury trial. So I want you to imagine that victim. For six years, it’s on hold. On pause. How are you expecting them to heal? How are you expecting them to move on?”

The 35 sworn officers in the SVU are just 2% of the 1,728 officers across the SFPD. The department is short roughly 500 officers, but the SVU remains a “major priority,” according to Public Information Officer Robert Rueca. Some of its attrition, he said, is due to the SFPD last year moving sergeants in financial crimes and missing persons units out of the SVU to general investigations. Since May’s hearing, the SVU has added four staff members.

Mayor Daniel Lurie’s Rebuilding the Ranks (opens in new tab) plan, announced shortly after he took office, includes short- and long-term solutions to the SFPD shortfall, including streamlining hiring processes and bringing back more retired officers to help with caseloads.

“We’re aggressively hiring,” said Rueca. “We hope to have more officers on the street and in our investigative units as soon as possible.”

It will take time for new recruits to move up the ranks and master the craft of SVU investigations. In the meantime, Flores’ proposed solutions range from simple to systemic. His biggest concern is housing — he dreams of a $10,000 line of credit that would allow the SVU to place victims in hotels when shelters are full, rather than investigators paying out of their pockets. But he recognizes that deeper change requires societal shifts.

‘We’re making a choice and a trade-off at the expense of the most vulnerable people in our society.’

Supervisor Myrna Melgar

“Everyone can blame the police, everybody can blame the courts or the district attorney’s office, public defenders,” he said, but “nobody has the right to hurt another person, period. You know, that’s kind of it.”

After nearly 44 years of working on the other side of that violence, Flores isn’t immune to the psychological toll.

“Even for me, there’ll be times when I’ll hear something and it’ll stimulate something for me — trauma for me,” he said. “I’ve seen a lot of stuff.”

As for how he avoids burnout?

“You mean besides walking out to the beach and screaming profanities into the air?” He is only sort of joking. Ocean Beach is where he often goes to get what he’s seen off his mind.

Mainly, Flores credits his family with keeping him grounded. He tried to give his three kids a childhood that was calmer than his own. There are hugs every day after work from his youngest, who still lives at home. His daughter told him some good news recently — he’s going to be a grandpa.

Few have been in the SFPD as long as Flores. Nobody wants to think about him leaving. “That’s why they’re playing, Hey, don’t retire,” he said.

Flores loves his job. He says he’s still “mastering the craft” and isn’t ready to say goodbye to the Hall of Justice. Not when there’s still so much work.

“It’s a dance,” he said. “It’s a dance that I know how to do.”