When students at Thurgood Marshall Academic High School heard they were going to have their phones taken for the whole day, every day, their eyes rolled out of their heads.

“What’s the meaning of it?” wondered Deshon when the policy was introduced in August 2024. He was skeptical, and many of his classmates were upset and unsettled.

Now, three weeks into his sophomore year, Deshon sees things differently. He realized the benefits halfway through last year, when he saw that his friends were “actually getting good grades and paying attention in class.”

“They weren’t just joking around like in middle school, when we had our phones,” he said, straight-faced and rocking a black jumpsuit with bumblebee-colored Jordans.

And so it goes. Deshon’s point of view was echoed by the majority of the teens The Standard spoke with at a recent visit to Marshall, the first public high school in the city to ban phones last year. The same views were echoed by students at St. Ignatius College Preparatory, which instituted its ban this semester, and at the private San Francisco Waldorf School, which has banned phones since 2023.

Educators and social scientists say the bans are a crucial (and simple) way to reduce teenagers’ dependence on screens. Nationwide, schools with bans have seen remarkable results, ranging from making students feel (opens in new tab) included to more unexpected outcomes like kids checking out more library books (opens in new tab) and using old-school cassette players for audio (opens in new tab).

The early success of the bans come amid the debate on how society views and regulates social media use among minors.

Last year, 41 states sued Meta (opens in new tab), the company that runs Facebook and Instagram, for allegedly strategizing to increase social media use among children. As a bill sits on Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk that would add warning labels to social media apps for young people, 14 states have issued outright bans on phone use at schools (opens in new tab) to increase student well-being. Last year, Newsom signed a bill (opens in new tab) requiring public schools to come up with policies to limit phone use by July 2026.

Still, while 74% of adults said they support phone bans during class time, just 44% think they should be banned for the entire school day (up 8% since last year), according to a recent Pew Research Poll (opens in new tab). Some of the loudest opponents to bans have been parents, who argue (opens in new tab) that in the case of an emergency, like a school shooter, students need access to their devices.

But what really matters is how the bans are going at the schools that have been bold enough to implement them. What teachers have found is that the change is ushering in something resembling traditional adolescence for their students.

Or, at the very least, a real life.

‘Black and white’

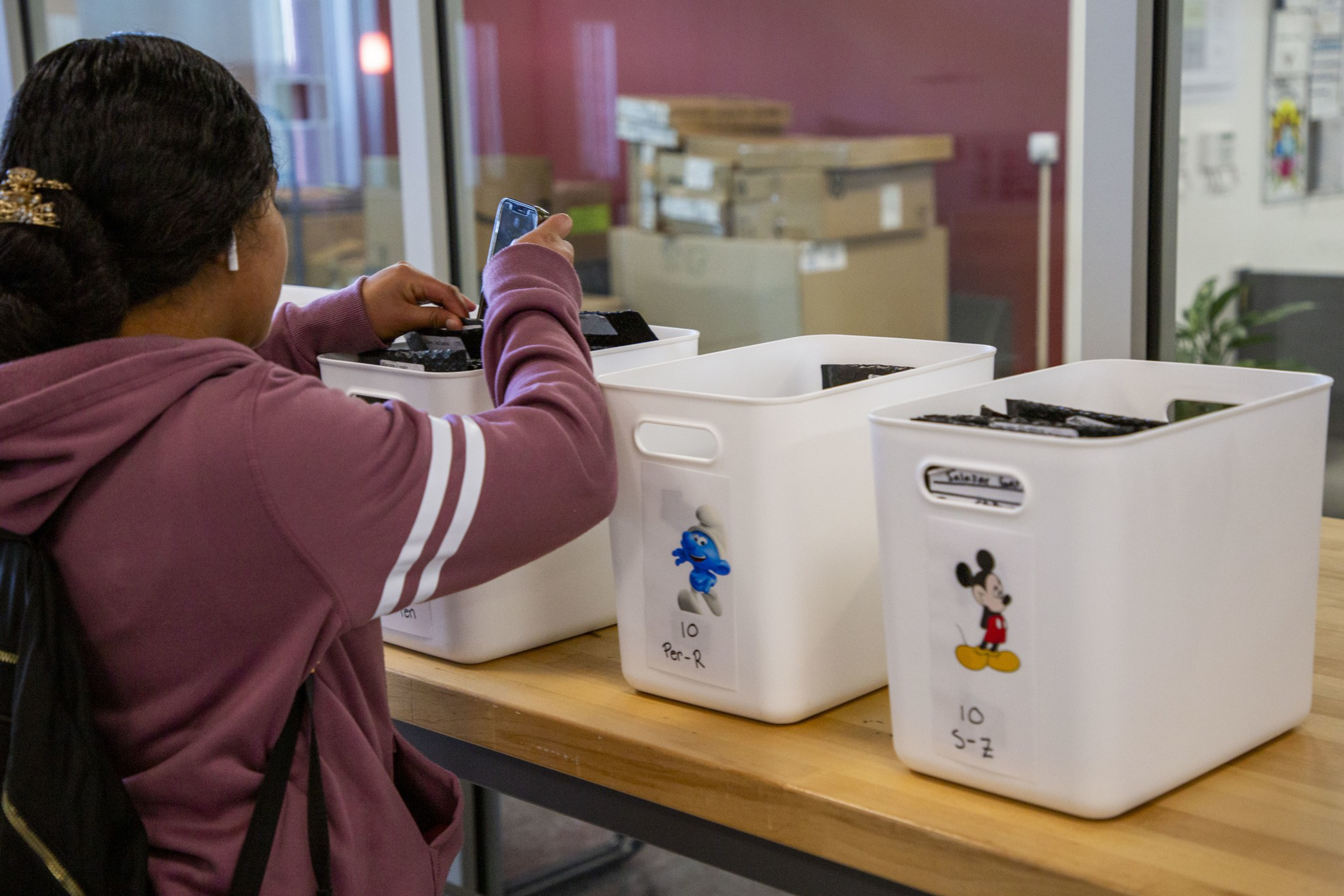

At Marshall, 13 bins greet students in the foyer. As the teenagers trickle in each morning, they fist-bump friends, say hi to teachers, and drop their phones into assigned bubble-wrapped envelopes inside the bins, labeled with names. As the day unfolds, there is not a phone in sight. Not in class. Not in the bathroom. Not in the hallways.

Greeting students as they walk in is Sarah Ballard-Hanson, the principal. She has a lot on her plate. “I could work 100 hours a week and still not be done with everything,” she said, walking down a hallway during a passing period. “It’s all about constant prioritization.”

That’s why ending the “constant power struggle” with students over phone use was crucial: When teachers are left to fend for themselves, they are forced to toe a tricky line between strictness and consistency, given that their colleagues might be more permissive about phones in the class. Now, said Ballard-Hanson, the rule is “black and white.”

“Every year we would talk about cellphones,” she said, “and every year there’d be the teacher who was like, ‘For the love of God, please enforce the cellphone policy.’”

Before the ban, teachers noticed students taking extra-long bathroom breaks or scrolling on their phones after finishing assignments. By contrast, when the ban was enforced, “students were actually interacting with each other” all around the Marshall campus, from the soccer fields to cafeteria tables, according to Grace Gould, an English teacher.

“It feels different,” she said. When asked if the ban is successful, she said, “A thousand percent.”

Now teachers don’t have to worry about phones until they bring out the bins at the end of the day. During school hours, students are learning stress management skills, said Ballard-Hanson, even while separated from the technology the world tells them they need in order to survive as adults.

“They want to go to something that’s soothing, and oftentimes that’s a cellphone,” said Ballard-Hanson, who said students from more disadvantaged backgrounds, many of whom speak English as a second language, are most easily distracted by devices.

One such student, Victor, a junior, told The Standard that without phones, “you can focus more in school and not on other things.”

‘Every year there’d be the teacher who was like, “For the love of God, please enforce the cellphone policy.”’

Marshall’s student body is around 80% Latino (opens in new tab), the highest proportion (opens in new tab) of any nonalternative, public San Francisco high school. Nationwide, Pew research shows (opens in new tab) that nearly all (95%) 13- to 17-year-olds say they have access to a smartphone, and 58% of Latino youth are on their phones “almost constantly,” compared with 37% of white kids.

“We are teaching kids how to self-regulate through discomfort,” said Ballard-Hanson. “That, to me, is going to be more of a benefit long term than teaching them how to use their cellphones appropriately in class.”

‘A rewiring of the brain’

The developments that preceded Marshall’s phone ban are familiar to every parent. There were flip phones, then there were smartphones and social media, and then there was Covid. Coming out of the pandemic, teachers and parents discovered that students were more antisocial and addicted to their phones than ever. Something had to be done.

The damage that phones have wrought on childhood was spelled out in the bestselling 2024 book “The Anxious Generation” by social psychologist and NYU professor Jonathan Haidt. It detailed what Haidt calls “the great rewiring of childhood,” when between 2010 and 2015, apps like Instagram and Snapchat burst onto the scene, and childhood went from mostly play-based to screen-based.

Haidt argues that children and teenagers’ mental health is worse now than at any point in recent memory — and worse than that of any other age group. The most alarming statistic in a sea of concerning ones (opens in new tab): The rate at which 10- to 14-year-old girls are treated in hospital emergency rooms for self-harm was four times higher in 2021 than it was in 2001, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The lessons of “The Anxious Generation” are on the minds of teachers at St. Ignatius, which instituted its phone ban at the beginning of this school year. Many teachers even keep a copy of the book on their desks, as the school gifted one to every staff member to help them understand the struggles facing youth.

Now, St. Ignatius requires students to keep their phones in their backpacks — technically the same policy that exists at many schools, but St. Ignatius is enforcing it, hard. With 1,500 students, the school is three times larger than Waldorf or Marshall. The administration plans to purchase magnetically lockable Yondr pouches (opens in new tab) but doesn’t have the funding yet.

Danielle Devencenzi, St. Ignatius’ assistant principal for academics and the architect of the ban, noticed after Covid that there wasn’t the “chatter or loud noises” from students in the hallways or classrooms that she had grown accustomed to in two decades of teaching.

The kids “weren’t as engaged as they normally were,” she said. “I think as teachers, we just kind of got used to it and just kind of let it happen.”

Walking with Devencenzi through the halls, library, and other common spaces on a recent schoolday, this reporter was struck by how much the kids were interacting or working. Students were chatting, playing board games or video games on iPads (allowed, so long as it doesn’t happen during class), working on homework together, or even — wait for it — reading books.

‘Instead of looking down on my phone, I look up and only see my friends.’

“Instead of looking down on my phone, I look up and only see my friends,” said Keeley, a sophomore. “I feel like people are more comfortable just going up and talking to certain people. When I have my phone, I’m uncomfortable, or, like, by myself.”

There was some resistance to the ban in the first weeks of its rollout. In an environmental science class full of seniors and juniors, one complained about getting detention without warning when a teacher spotted a phone on them in the first few days of school.

“They didn’t really ease us into it,” the student said.

But Devencenzi believed the Band-Aid had to be ripped off. In the first three weeks of school, administrators collected around 75 phones that students failed to keep in their backpacks (a pocket isn’t good enough). “Students have developed an addiction to this device, and so it’s hard for them to withdraw from it,” she said. “It’s a rewiring of the brain.”

Some complained that since everyone still has an iPad, the distractions haven’t gone away — but now it’s just harder to check the time or change a Fantasy Football lineup.

A senior noted that some of her antisocial classmates seem even more anxious now that they can’t use their phones as a lifeline. On the other hand, she said, the ban has clearly been staving off cyberbullying.

“Social media opens that possibility for people to just project their insecurities onto other people and just hate openly without facing the consequences,” she said.

Most students agree that even a few weeks into the ban, the pros outweigh the cons.

“During my [free periods], I’m more productive, because I would spend it on my phone, like, playing games,” said Keon, a junior. “Since there’s a phone policy now, I definitely spend it more doing homework.”

“Lunch and breaks are more sociable,” added a junior girl. “I’ve met some new people through this policy.”

Students expressed the sentiment that their phones and social media had taken over their lives, even if the technology helps them “relax” and “feel happy.”

A Gallup survey (opens in new tab) from October 2023 showed that teenagers spend an average of 4.8 hours a day on TikTok, Instagram, and other social media platforms — but that didn’t factor in SnapChat, the messaging and social media app that one student said was doing the most damage among peers.

“Social media has been a big distraction for me,” said Natalie, a St. Ignatius senior. “I think it’s a big issue: the amount of time you spend not learning anything or not having interactions with, like, an actual human being in front of you.”

‘I don’t want to be scrolling’

Other San Francisco high schools have ramped up enforcement of their phone policies this school year, according to staff, parents, and students. Teachers at public high schools, including Lowell and Washington, have scolded students for looking at phones or listening to music on headphones during passing periods; during class, teachers are using pouches to store students’ devices.

But, without a full-day ban, there are complications — and, for better or worse, social life on campus still largely revolves around phones.

A Lowell student said one teacher uses the pouches to take attendance, counting as absent anyone who doesn’t have a phone in the pouch. A student came up with a workaround by putting a calculator in the pouch, then skipping class; the others found it hilarious that the teacher didn’t notice the kid was missing. One said there are teachers who, during class, “don’t even really notice we’re on our phones, or they don’t care.” Another Lowell student said wireless internet on campus can be spotty, so kids feel like they need their phone for its hot spot.

University High School, a private school, has chosen not to enforce a phone ban out of safety concerns, a school official told The Standard. A representative of Lick-Wilmerding High School said it likewise doesn’t “have a specific phone policy or ban.”

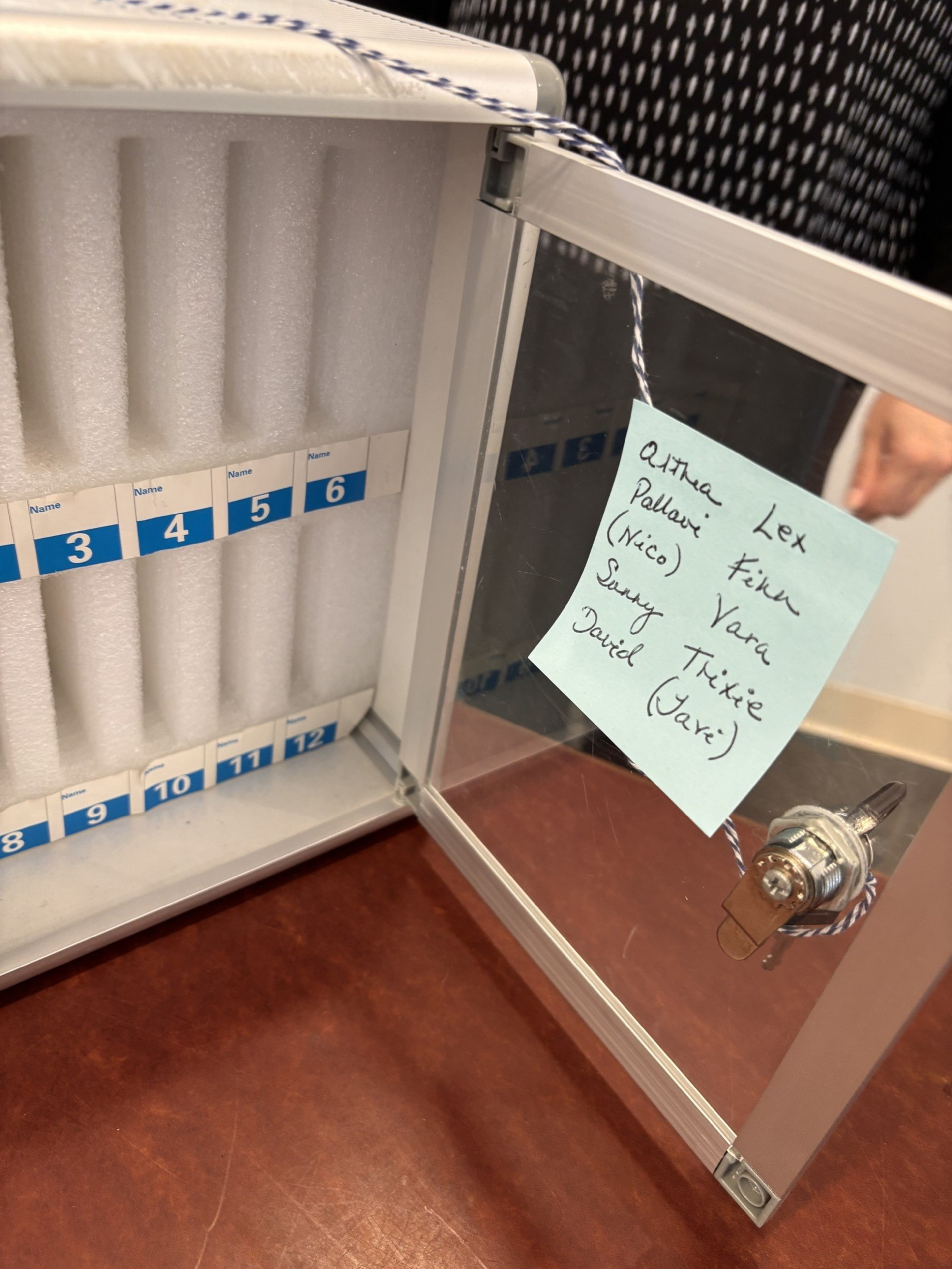

San Francisco Waldorf High School, on the other hand, has had a full-day phone ban for three years; as soon as kids enter campus, their phones are stored in safe-like boxes in the office.

Chris Cary, a U.S. history teacher at Waldorf, was previously at Marshall. While at the public school, Cary used pouches to collect phones and was steadfast in the belief that just having a phone in your pocket (opens in new tab) can damage attention span, even if it’s not being used.

Cary lamented the fact that he would have to take up a few minutes at the beginning of class just to make sure no one had a phone. He didn’t like seeing kids get excited about fights in school and videotaping them.

But, he said, being strict was worth it, even if it alienated him from some annoyed students. “It was a hill I was willing to die on,” Cary said.

Now, teachers at Cary’s former and current school say they spend more time teaching and less time disciplining. And regardless of whether students think the bans are stupid, teachers say kids have become more outgoing.

And students are grateful for the reprieve from constant screen time. As Waldorf senior Yuumi put it, “I’m very incapable of stopping myself from staying on my phone.”

But at all three schools, kids said that phone bans inside schools don’t equate to less usage outside of them. They spend the entire school day without their phones only to find themselves — not to mention all the adults around them — lost inside their devices as they take public transport home.

“My screen time is crazy,” said one St. Ignatius student. “It’s really bad.”

They don’t want it to be that way forever.

“It’s a little worrying, the rate we’re all addicted to our phones,” fretted Audrey, a Waldorf senior. “I don’t want to be scrolling TikTok when I’m 30.”