Miguel Sandoval was in the middle of lunch Wednesday when he got word that the city was towing the trailer where his two teenage siblings have lived for six months.

He put down his food and raced to the Bayview corner where it was parked. But he was too late.

“I’m trying to get the permit. I’m trying to get the permit,” he pleaded with city workers as the home was lifted by a tow truck. Sandoval, who lives in a homeless shelter with his wife and toddler, said his younger siblings’ application was denied because the trailer wasn’t registered in his name. His 15-year-old brother was at school and his 18-year-old sister was at a job interview, he explained.

He fought back tears and his dog howled as the tow truck dragged the trailer, along with most of his siblings’ belongings, down Ingalls Street. Once it was fully out of view, a city worker approached to ask Sandoval if he and his siblings had shelter.

“This is bad, very bad,” Sandoval said after the city workers had left. “That’s everything they own.”

The Sandovals were some of the first homeless people to lose their shelter in San Francisco’s new crackdown on RV encampments. Just after 9 a.m. Wednesday, a posse of more than a dozen police and city staffers from across departments swarmed the Bayview to tow and cite trailers and RVs. At least one occupant wasn’t present when the city dragged their wheeled home away. Others were able to move their vehicles in the nick of time.

Mayor Daniel Lurie unveiled the RV strategy in June, billing it as an approach that would balance enforcement, compassion, and deterrence. Those living in vehicles deserve an opportunity to move indoors, Lurie said, but the city could not allow long-term RV encampments on its streets. Through a permit program, officials would offer temporary refuge to RV dwellers — as long as they agreed to eventually get rid of their RVs and accept housing. Anyone else who parked their RV on public property after Nov. 1 faced the loss of the vehicle.

But the plan has hit some snags. As of Wednesday, there were at least 80 unpermitted large vehicles in the city, according to data shared by the Department of Emergency Management. While some longtime residents never received a permit, others who arrived after the Oct. 24 deadline did. And among those who were granted official vehicular refuge, The Standard spoke to one who isn’t homeless — but whose camper van is nonetheless protected by a coveted permit bumper sticker for the next six months.

Some RV dwellers say they’ve had access to more resources since the plan was announced, expressing optimism over the city’s promise of housing. But most — including several permit-holders — paint a picture of anxiety, desperation, and confusion as their time runs out.

‘I’m a San Franciscan’

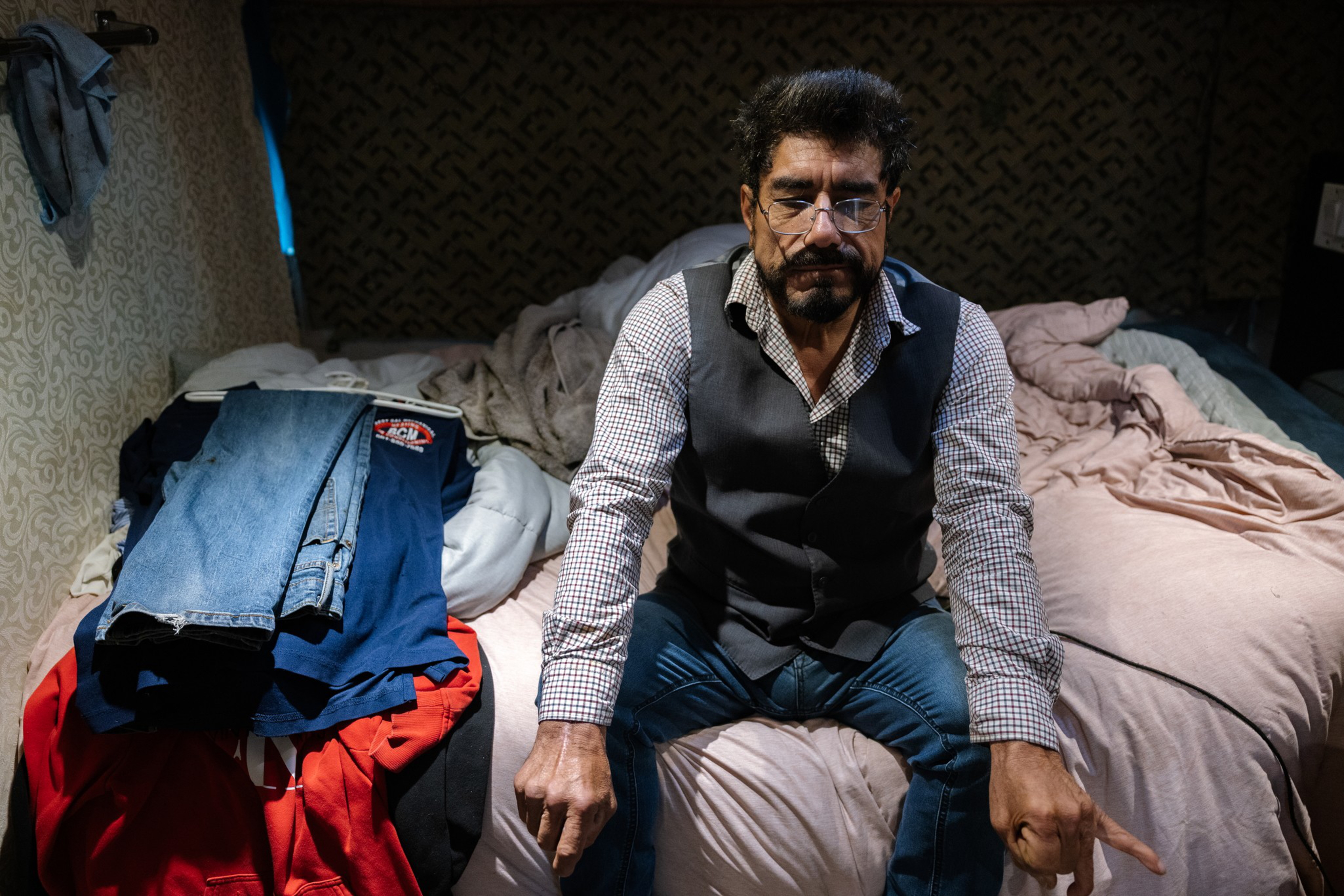

When Jose Arambula learned of the city’s new permitting process, and the housing promised alongside it, he thought his prayers had been answered. He hoped that finally, nearly 15 years after a bitter divorce left him homeless, he’d have a chance to leave the streets behind.

By now, Arambula was all too familiar with how things work in San Francisco. Every week for more than a decade, he’d borrowed a friend’s truck to move his trailer and avoid parking enforcement officers. Even so, it’s been towed twice. On one occasion, after retrieving it from the impound, he found that thousands of dollars in clothes and tools were missing, he said.

Still, he thought this time would be different. The city’s plan to clear dozens from RV encampments promised to provide a pathway to stable housing in return.

In the months following the city’s guarantee of housing, outreach workers approached Arambula at least four times. He began to imagine a new life — one in which his three children wouldn’t have to visit him on an industrial street corner in the Bayview, catching up over the roar of passing trucks.

But with every visit by the outreach team, Arambula’s optimism faded. They asked for the same basic information repeatedly, he said. And their assurances of housing — or even a temporary permit for his trailer — never materialized. He didn’t understand why. But he began preparing for the worst.

“They can take everything, but just don’t take the dog,” he said Monday, looking down at his 6-year-old pitbull mix, Kira, who was gnawing on a bone.

Arambula isn’t alone. Parked on the same block of the Bayview, 70-year-old Bob Kaufman was still scrambling this week to obtain a permit for one of his RVs, which houses his 80-year-old friend Mike, who has dementia.

At another hot spot across town, more than a quarter of the two dozen RVs parked on Lake Merced Drive were missing permits just two days before the Nov. 1 deadline. Inside one, an SF State student, who asked not to be named but identified herself as a veteran, said her application had been denied.

“The same people trying to give us permits, they’re also trying to take our RVs,” the woman said. “Honestly, my plan at this point is to just rack up all the tickets.”

By Wednesday morning, Arambula was among those who awoke to police threatening to tow his home. Before they could, he managed to borrow a friend’s truck and drag his trailer to another location — at least one more time.

“It’s just not fair,” he said. “I’m a San Franciscan. I’ve spent half my life here. My daughter was born here. I love this city. I’m not leaving even if they force me to.”

Directly across the street, Mike Price, a lifelong city resident, faced a similar brutal wake-up call. Price shot up from bed Wednesday morning and started gathering his belongings, begging the police for a chance to move while he continues to work on getting a permit.

“It’s horrible; there’s no words to describe it,” Price said after he found a nearby alley where he hid the RV. “It’s worse than being in a fire or a tornado.”

‘Cops don’t have to abide’

Those who haven’t received permits say the city’s process has been disorganized from the start. Unless their vehicle was logged during the eight-day survey in May, many were deemed ineligible. They question how the city could be certain its workers tallied every vehicle — or why permits weren’t simply distributed during the count.

The city has also apparently not followed its own initial guidelines in determining permit eligibility. On a dead-end street just a few blocks from Arambula, a young Venezuelan couple received a permit for their recently purchased RV within a week of their arrival in late October — months after the May survey.

The city contends that the survey captured most of the people it intended to. During the count, city workers tallied 437 vehicles that appeared to have people living in them. By September, only 178 such vehicles could be found in the city — 161 of which had successfully obtained a permit. The city reported 404 large vehicles as of its last count in September, and 322 permits issued in total. Roughly 100 of those were issued in the final days before the enforcement deadline, but dozens of San Franciscans were still left without refuge.

The city did not respond to concerns about the application process many RV dwellers reported, or about people who received permits that did not comply with the program’s rules. In a statement, the Department of Emergency Management said it will continue to work with people who have lost their RVs to the city’s new enforcement and it pointed to investments in housing set aside for people living in vehicles.

A permit is only a temporary reprieve, good for six months while the city attempts to move RV dwellers into housing. And however sought-after, it is no guarantee of safety.

When the city towed Kurt Shuptrine’s RV for outstanding tickets last month, it felt like watching his life disappear. With it were all his possessions — and the shiny blue parking permit from the Homeless Outreach Team that was supposed to protect them.

For more than a week, Shuptrine and his friend Tony Crust tried to retrieve the RV as impound fees climbed to more than $1,000. By losing his vehicle, he feared, he would also lose his place in line for housing — though the city contends that housing is accessible without a permit.

Shuptrine slept in his Honda CRX sedan until he and Crust discovered a loophole that allowed him to win back his RV for $85. Relief washed over him when he got the vehicle back, but so did a haunting realization: The parking permit had done little to protect him.

“The permit? Cops don’t have to abide by that,” Shuptrine said. “They give me so many tickets. I got $6,000 worth in no time, and I have a handicap sticker in my window.”

Even with a permit, RV dwellers must follow all city parking laws except the two-hour limit. They’re also bound by San Francisco’s “good neighbor” policy, which requires keeping sidewalks clean and quiet. And they must stay engaged in case-management services, accepting any housing offered — whether temporary or permanent.

Those delicate conditions have many permit-holders anxious. Guillermo Mazariegos, whose trailer is held up by two wooden blocks, said he has hardly moved from his corner in the Bayview in nearly a decade. But he knows he’s on borrowed time.

“I don’t know if I have the right to be here, and they could come at any time and make me disappear,” he said. “If they throw my things away, I just might end up sleeping in that tree.”

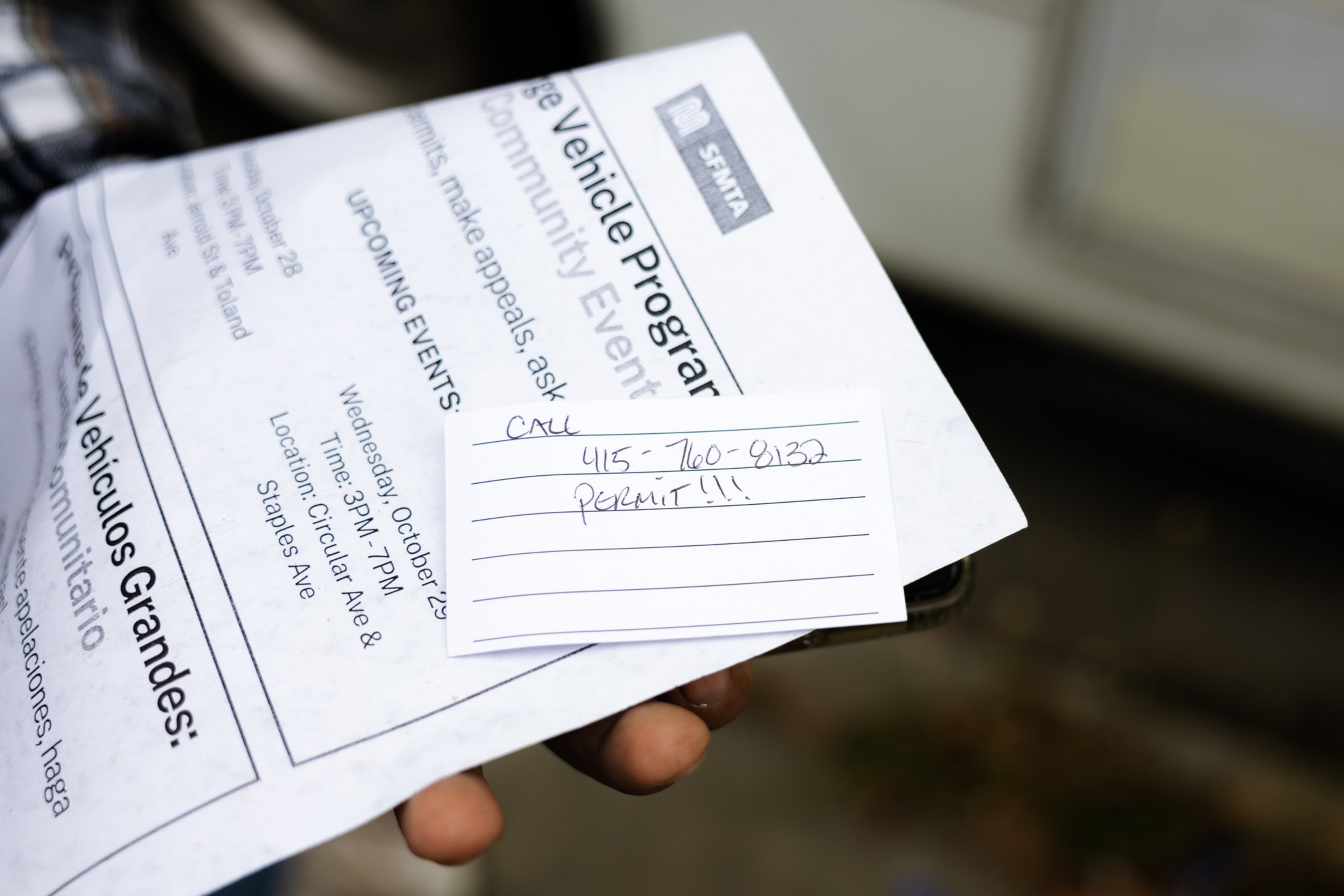

For other permit-holders, the stakes are lower. Less than 48 hours ahead of the citywide RV ban taking effect, Oved Hidalgo didn’t have his parking permit. He was frantic, working the phones and pleading with city workers in an effort not to lose his beloved camper van.

Then, just a day before the Nov. 1 deadline, a member of the Homeless Outreach Team gave Hidalgo his shiny blue saving grace. His RV was safe.

But there was one thing separating him from the hundreds of other RV owners scrambling for a permit: Hidalgo isn’t homeless. He and his family live in an apartment in the Bayview, down the street from his camper van’s parking spot. He received the special sanction for a vehicle he uses to take his four kids on vacations.

“I just use it on the weekends to go out with my family,” Hidalgo said. “I need to be able to park it somewhere.”