Each evening for nearly two years, Ezra Berman and Miles Palliser rolled out AstroTurf, space heaters, and seven televisions onto the corner of Grand Avenue in Oakland, only to break down their setup and bring it indoors a few hours later.

The owners of the Oakland Athletic Club had no other choice. It was the height of the Covid pandemic, and Berman and Palliser wanted to keep their new sports bar alive to provide fans with a much-needed gathering place.

Even if local teams were abandoning the city.

“We set out to open a sports bar,” Berman said, “and what we’ve realized, in part because the sports teams have left, is that we’ve actually become more than just a sports bar for the community.”

The Oakland Athletic Club, known to regulars as OAC, opened in 2018. It was supposed to be a straightforward expansion of the San Francisco Athletic Club, the popular spot on Divisadero Street that Berman and Palliser opened in 2014. (The SF outlet was sold this summer to new owners who renamed it TimeOut Tavern.)

Almost immediately, OAC was hit with a double whammy: The pandemic shut down businesses, and the professional sports world in Oakland went dark. In the past six years, the Warriors left for Chase Center in San Francisco, the Raiders departed for Las Vegas, and the A’s bolted for Sacramento with the hope of eventually moving to Vegas.

Section 415: KNBR’s Adam Copeland on the future of sports talk radio

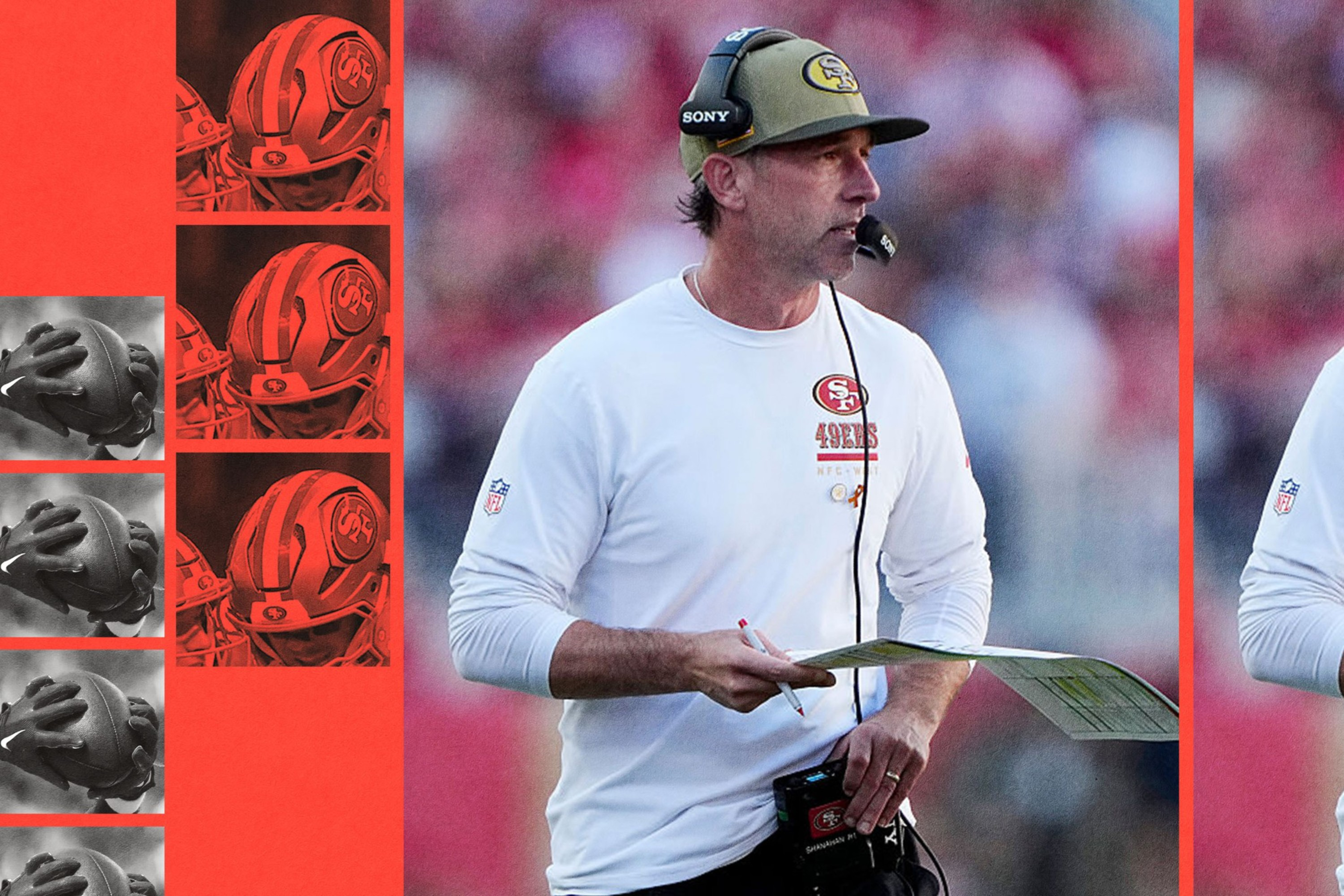

Section 415: Brock Purdy, Mac Jones, and the 49ers’ path to the playoffs

Section 415: Making sense of the Warriors’ uneven start

For many East Bay fans, this was more than a loss of their teams. It was a threat to their identity.

“When you are a sports fan, it’s not something that you do; it’s something that you are,” said Paul Freedman, co-owner of independent pro baseball team the Oakland Ballers. “It’s your sense of pride and happiness, so to lose the teams was a big hit. It was collective trauma for the city of Oakland.”

Freedman, a childhood friend of Berman, spent countless hours at OAC’s makeshift outdoor arrangement. These days, everyone is back indoors, watching the Warriors on TV and sharing plans for how to keep Oakland’s sports scene alive.

Freedman remembers the sleepless night spent assembling the Ballers’ lockers alongside family members just two days before the team’s 2024 debut at Raimondi Park. The Pioneer League franchise became, as Freedman says, “a minor-league team in a major-league market.”

The Ballers were born because Oakland was losing the A’s. Professional soccer teams the Oakland Roots and Oakland Soul, founded in recent years, are also working to fill a void left by departed franchises.

“People were looking for a place to turn,” Palliser said. “Oakland is still full of Raiders fans, A’s fans, and Warriors fans looking for an outlet. We became a more important place for them to gather.”

Out of loss came reinvention. As outsiders gave up on Oakland, the city built its own playbook — one grounded in local ownership and grassroots funding.

Freedman and his Ballers cofounder Bryan Carmel offered individual investors pieces of the team through a crowdfunding campaign. The model lets everyday Oaklanders become literal stakeholders in the next chapter of their city’s teams.

So far, it’s working. The Ballers’ grassroots push raised more than $3 million from 2,500 investors. The fanbase grew not just widespread but passionate — Freedman is still in awe when he notes just how many “Ballers” tattoos he’s seen just two years into the organization’s existence. The Roots and Soul rolled out similar crowdfunding offerings for fans-turned-investors. “Oakland is saving Oakland,” said Freedman. “The people of Oakland are saving Oakland sports.”

That same concept anchors the next chapter for the Oakland Athletic Club. Berman and Palliser are launching a tiered crowdfunding campaign they’re calling “OAC 2.0.”

The next version of their sports bar is a chef-driven remodel timed between February’s Super Bowl and the start of March Madness. In partnership with executive chef Paul Iglesias and hospitality director Sophia Akbar — the couple own Oakland restaurants Parche and Jaji, just blocks away — the campaign has eight investment tiers for supporters of the bar’s next iteration.

Berman and Palliser are offering up 20% equity in the business, selling shares at $100. The owners believe OAC is underutilized when games aren’t in action, and with better food, better drinks, and a dedicated space to host events, the venue will attract customers who aren’t diehard sports fans.

To Palliser, the prime incentive for bar investors mirrors the one that brought so many backers to the Roots and Ballers. “Imagine coming in here, sitting down for a Roots game, and saying, ‘I own part of the team. I own part of this bar.’” T

Those local ties go beyond what’s on the screens. The OAC has also formed official partnerships with both the Roots and the Ballers. The relationship with the Roots began in 2019, when the team’s organizers called Palliser in a panic before their first four-game season, asking for help running concessions. The OAC team stepped in — and in return, Roots fans packed the bar for away games. The same collaboration now extends to the Ballers.

The reinvention looks like neighbors investing in neighbors and fans owning their fandom. On Grand Avenue, in Raimondi Park, in the Oakland Coliseum — local hands are building The Town’s athletic future.