Most local music fans will be familiar with Bill Graham on some level, even if only subconsciously. Reminders of his influence and monuments to his life’s work—which was devoted to harnessing the countercultural ethos of rock & roll and molding it into a mainstream economic engine—are all over the city and the broader Bay Area.

Dedicated concertgoers have almost certainly spent time in one of the many venues where he made his name as San Francisco’s larger-than-life concert impresario. The Bill Graham Civic Auditorium, just a stone’s throw from City Hall, is the most conspicuous monument to the man.

But in his time he also helped transform the Fillmore into a nationally recognized venue and built Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View from the ground up. And that is to say nothing of all the many local halls, theaters and arenas he used as vessels for the thousands of concerts he organized in his lifetime.

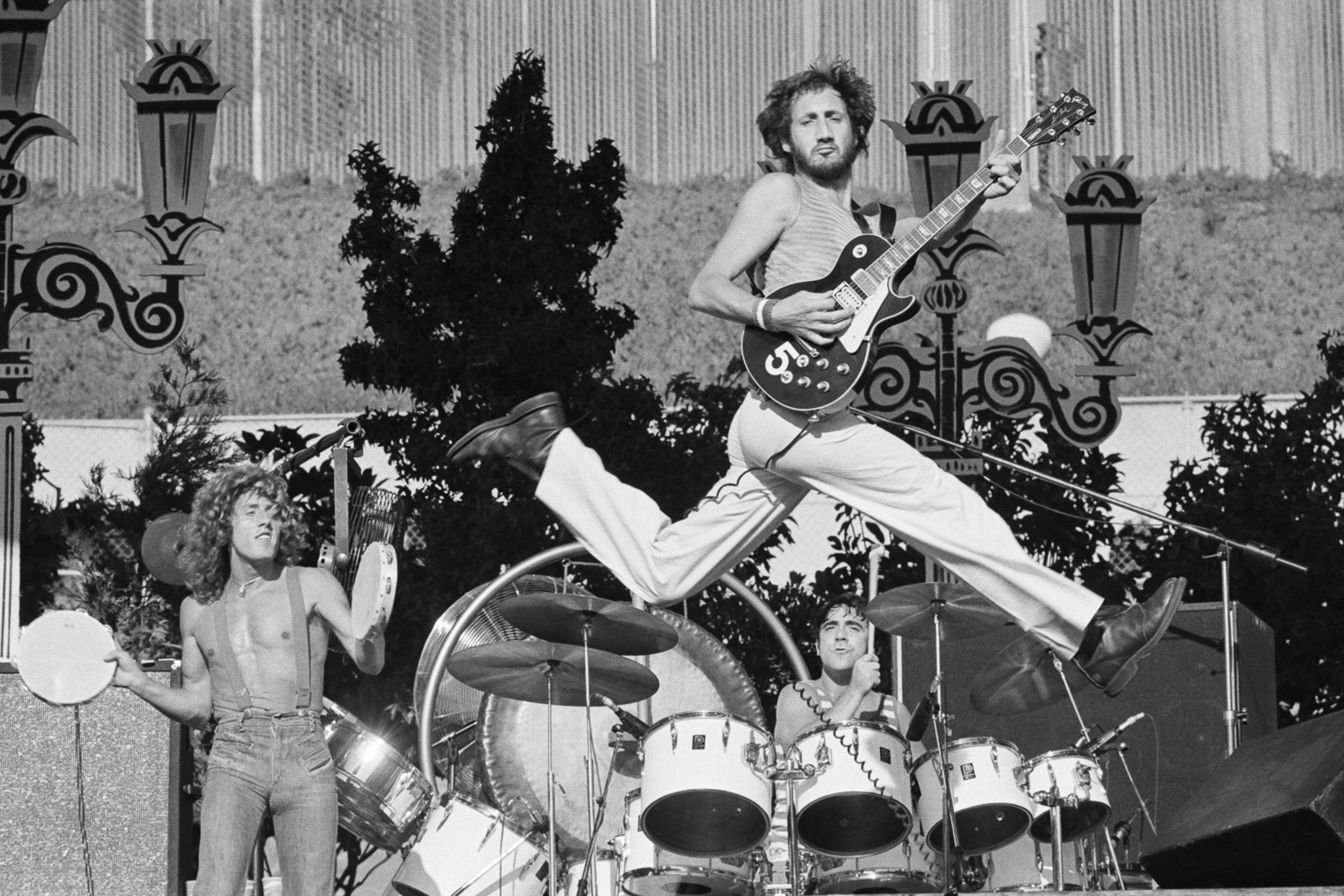

The legendary promoter’s presence looms large over Into the Mystic: A Visual History of Bay Area Rock Palaces. The exhibition of photographs—either owned or taken by local concert photographer and historian Jay Blakesberg—is now on display and available to view by appointment on the ground-floor warehouse of The Standard’s headquarters in the Mission District. It features images of rock & roll icons performing at Bay Area venues either owned, managed or booked by Graham.

“All these venues were so important,” Blakesberg said on Wednesday night, at the opening reception for Into the Mystic.

In a conversation with Jerry Pompili, a former house manager of the Fillmore and the Winterland Ballroom, and Ben Fong-Torres, a former editor and writer at Rolling Stone, Blakesberg noted that long before San Francisco became known as a hub for tech, he and his friends in New Jersey thought of the city as a rock & roll mecca. Eventually, Blakesberg noted, he would come to understand that while the beats and the hippies each deserved credit for transforming this seven-square-mile peninsula into a magnet for creative musical expression, it was Graham that stitched it all together into a cohesive whole in the 1970s and ’80s.

Pompili, who eventually worked his way up to a leadership position within Graham’s empire, repeatedly underscored his old boss’ holistic approach to concert promotion and management. He fretted over the details, Pompili said, striving to ensure that every aspect of the concert experience was comfortable, enjoyable and memorable for both the fans and the talent.

“Bill used to say, ‘If we piss them off in the parking lot, they weren’t going to have a good time at the show,’” Pompili remarked.

In an interview after the panel discussion, Fong-Torres—who wrote about Graham and the shows he organized for Rolling Stone—said that it was not an exaggeration to say that he was one of the most important concert promoters to have ever lived.

“In his time he was as big as even he himself might have said he was,” Fong-Torres said. “There’s no question that when he died”—tragically, in a helicopter crash in 1991—“it was the death of one of a kind.”

But Graham’s influence on the rock & roll industry stretches well beyond concert promotion and venue ownership and into far less obvious corners of the concertgoing experience.

In fact, a case could be made that everything from the state-of-the-art soundsystem at the Chase Center to the security team working door at The Warfield wouldn’t be the same if it weren’t for Graham. Even that ratty T-shirt with your favorite band’s name silkscreened across the front can be traced back to a decision Graham made half a century ago at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom.

Mixing Business & Pleasure

It was sometime in the early 1970s. Graham was managing a Grateful Dead concert at Winterland—a former ice skating rink turned rock & roll venue at the corner of Post and Steiner streets on the edge of Japantown—when a member of the band’s coterie asked him who she should see about selling T-shirts during the show.

Graham, in directing her to one of his employees, took the first step toward the creation of Winterland Productions, which would go on to become the leading merchandising and licensing company in the early days of the rock industry. In its heyday, Winterland Productions produced shirts for artists like the Rolling Stones, Fleetwood Mac and Madonna. In the process, it turned what had previously been an amateur side hustle into a big money enterprise.

Another of Graham’s lesser-known contributions was the professionalization of security services and crowd management at live shows. These days, many large venues and permitted outdoor concerts follow best practices developed in part by Graham and his team.

But it wasn’t always that way. According to his autobiography, Graham was an outside advisor to the organizers of the ill-fated Altamont Free Festival in 1969 (opens in new tab). In his book, Graham writes that he at first advised the organizers to give up on the show due to safety concerns, but ultimately lent them some stage hands. By the night’s end, a concertgoer had been stabbed to death by a member of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club—who, according to legend, were paid in beer to provide security for the Rolling Stones.

Pompili, who served as the company’s security chief at a number of different venues said Graham had a maniacal focus on safety, which resulted in a number of innovations. One, according to Pompili, was the idea of rock show medicine. Graham, a longtime supporter of the Haight Ashbury Free Clinic, linked up with the facility to staff up the company’s major outdoor festival events like the annual Day on the Green at the Oakland Coliseum.

“Based on the types of shows we were doing, we knew there was going to be drunks and overdoses, we realized that unless we did something someone was going to die,” Pompili said.

When Graham recounts the stories of his earliest shows in his autobiography, the groovy psychedelic scenes make an appearance, but so do the pages and pages of notes he made on access and egress for the audience.

Connecting the Dots

Back in the early days of rock & roll, national tours were organized in a piecemeal fashion. It was a game of connect-the-dots with numerous promoters running individual fiefdoms in markets across the country. Graham turned that model on its head when he started promoting major national tours for stars like Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, George Harrison and the Rolling Stones.

Graham’s approach—which some in the industry applauded but others disdained—involved cutting out talent agencies and booking shows directly with promoters in individual markets.

As rock music migrated from sweaty underground clubs to the mainstream through massive stadium tours, a technological shift was also necessary to amplify the music in a way that could be appreciated by fans in the nosebleeds. It’s widely recounted that the Beatles, who quit performing live at the end of their 1966 U.S. tour, did so in part because they couldn’t hear themselves over the incessant screaming of fans. The truth is that their fans were loud, but the soundsystems they played through were often woeully insufficient. The way Pompili tells it, at their final concert at Candlestick Park, the Fab Four were piped through the ballpark’s public announcement system, which was designed to tell fans it was time for the seventh inning stretch, not to faithfully render boundary-breaking sonic explorations of Revolver.

“In the old days the concert promoter just booked the venue and transported the band,” Fong-Torres explained. “It was perfunctory. It was disrespectful of both the artists and the fans.”

To help usher in a new era of large, live rock shows, Graham launched FM Productions, which was one of the first companies dedicated to lighting, staging, sound and production for rock concerts.

It was at the Fillmore during this era where some of the earliest psychedelic light shows were developed and forever influenced how rock concerts were staged and presented.

Graham eventually controlled the entire concert promotions business in the Bay Area; the one piece that was missing was owning his own venue, which would give him extra leverage over the concert scene. His team eventually settled on the Shoreline Amphitheater in Mountain View, which they built on the site of a former landfill on the edge of the Bay by securing a loan from the city of Mountain View and cobbling together contributions from socialite Ann Getty and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak.

By the 1980s, Bill Graham Enterprises had developed into a precursor of the major entertainment conglomerates live music fans will recognize today. There was Bill Graham Presents, which was focused on booking shows, but also a development arm and an artist management company. They even had a catering division called Fillmore Fingers and an internal marketing agency called Chutzpah Advertising.

A Lasting Legacy

And of course, there was Graham himself, who became the prototype for the hard-charging rock businessman. With a brash New York sensibility and a flair for the theatrical, he brought his unique persona to all of his productions. Graham, it is said, always wanted to be an actor.

He threatened, he cajoled, he convinced, he ball-busted, he exploded, he performed.

He was noted for spending a portion of his profits in upgrading bands’ dressing rooms, wining and dining and entertaining the acts, and endearing himself to the artists he promoted, which allowed him to drive harder bargains.

“When Bill walked into a room he had a presence that was pretty heavy-duty,” said Rita Gentry, who spent two decades working at Bill Graham Presents. “He could be on the phone screaming ‘fuck you, fuck that’ and everything else in the world, but open the sliding door and ask really sweetly for me to do something.”

There was a side of his personality formed by his childhood as an orphan who fled Nazi Germany. Friends and colleagues say Graham had a profound sense of fairness that bled into his desire to use his talents and business to do good. In fact, some of the first concerts he produced in San Francisco were meant to raise funds for the radical performance company, the San Francisco Mime Troupe.

As his production company began to take off, his ambitions became grander. Take 1975’s S.N.A.C.K. Sunday for example. After hearing that afterschool and sports programs at San Francisco Unified School District were being threatened by budget cuts, he quickly organized a benefit show at Kezar Stadium that featured musicians like Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Joan Baez and Santana.

Some three decades after his death, the people that knew Graham still speak of the gravitational pull of such a singular figure.

“You know Bill has been dead for 30 years, but we still have a community of people who either worked directly in Bill’s companies or were touched by him in some way,” Bonnie Simmons said. “It could sometimes have its loud moments and its fractious moments, but we knew if Bill trusted you, he totally had your back.”

‘Into The Mystic: A Visual History of Bay Area Rock Palaces’ can be viewed by appointment at The Standard’s event space. Contact [email protected] to arrange a viewing.