A decade-long bull run for tech stocks is showing signs of a slowdown, with the valuations of many tech firms plunging in recent weeks alongside a broader market slide. And it isn’t just stock market investors who are feeling the pain; the market declines are poised to hit San Francisco’s tepid economic recovery, too.

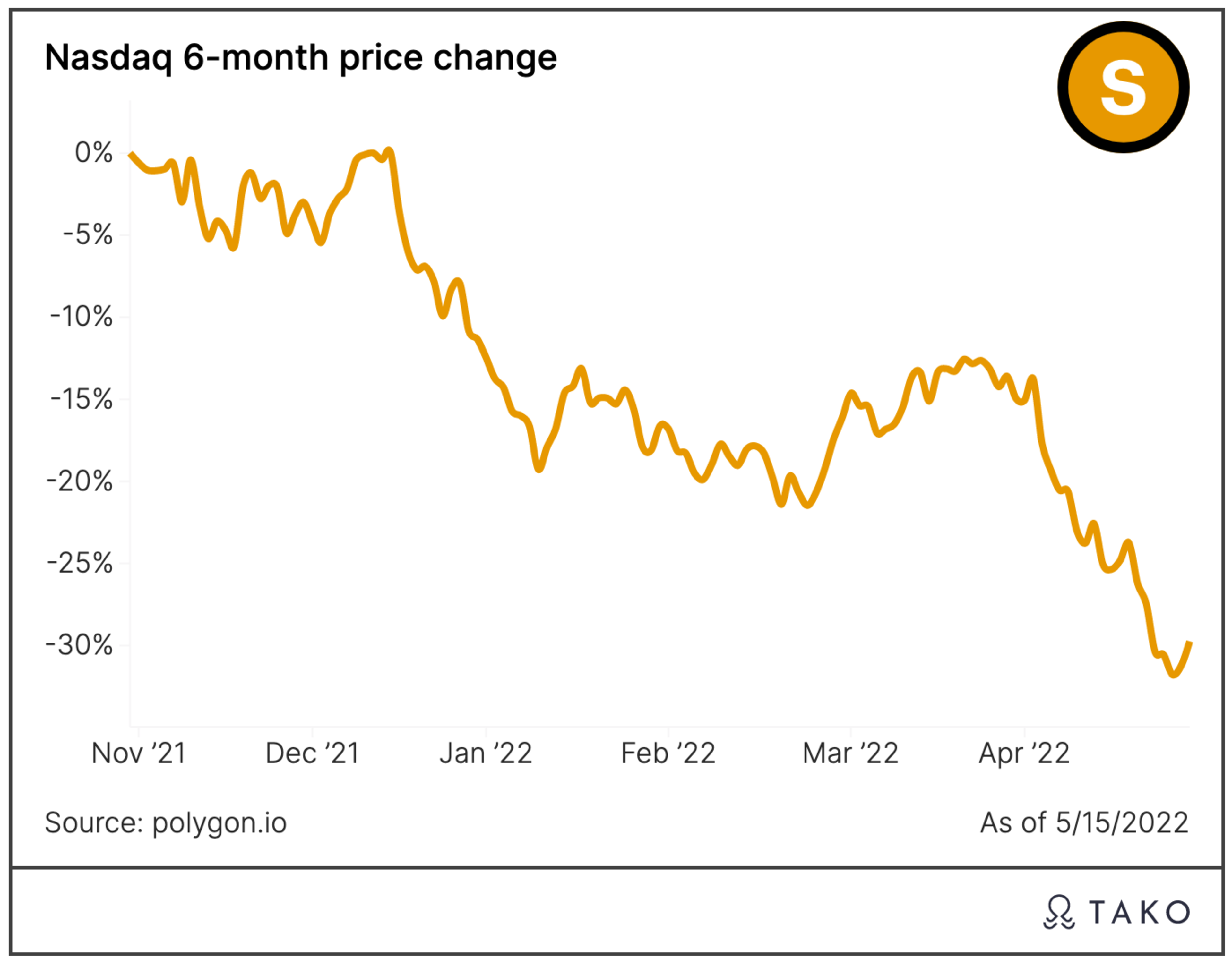

The tech-heavy Nasdaq index is down more than 25% since the beginning of the year, and that plunge includes a number of blue-chip firms based in San Francisco: Uber, Lyft, Okta and Twilio are each down more than 40% year to date, and analysts caution that market turmoil could continue alongside continuing inflation, interest rate hikes and geopolitical risk tied to the war in Ukraine.

But the downturn in tech stocks, paired with trends in the city’s startup ecosystem, could spell particular trouble for a local economy that has found itself reliant on the strong performance of the tech sector for job growth, economic activity and city finances. Tech workers make up roughly 15% to 20% of the total workforce in the San Francisco area, according to Ted Egan, San Francisco’s chief economist, but have had an outsized impact on the region’s recent economic growth. When those jobs go away, it ripples across the city at large.

“When the heat is on to achieve profitability or the heat is on the market to come up with reasons to buy their stock, we see companies become more cost-conscious,” Egan said. “That means implications around hiring, real estate and a bunch of other things that can affect the local economy.”

Lean(er) Times for Startups

The decline in tech stocks is also cascading into the startup world—a longstanding strength of San Francisco’s economy—as valuations tumble and investors change their focus from an emphasis on growth at all costs to profitability.

Venture capital investing saw a nationwide slowdown in the first quarter of 2022, and San Francisco was no exception. The money invested in local startups fell to $2.7 billion in April from a pandemic high of $7.3 billion last August.

Despite any outmigration tied to the pandemic, the Bay Area remains far and away the largest market for tech startups; San Francisco is home to many of the most valuable startups. But winter may be here for startups that have long enjoyed sky-high valuations.

Zach DeWitt, a partner at Wing Venture Capital, said that valuations could come crashing down to earth as the market reckons with the pricing of tech giants that have already gone public. Under the new funding environment, startups are likely to spend less, cut staff or make other efforts to make their cash reserves last.

“What we’re seeing in the stock market is a re-rating of the public software companies in terms of their valuation…and when you look at the private markets, those valuations are even more exaggerated,” DeWitt said. “People just stop and wait, based on the old adage that nobody wants to catch a falling knife, and everyone is trying to figure out where the bottom is.”

Job Cuts Mount

As investors grow more skeptical of sky-high valuations, more tech companies are tightening their belts in the form of layoffs.

Layoffs.Fyi (opens in new tab), a tech industry layoffs tracker launched at the beginning of the pandemic, shows 73 major layoffs in 2022 thus far, nearly double the number of layoffs last year. Fourteen of the companies tracked which have conducted layoffs this year were based in the Bay Area. Other local firms, such as Twitter, Meta and Uber, have frozen hiring (opens in new tab).

Roger Lee, the founder of Layoffs.Fyi, characterized the current jobs cuts as the “second wave” of startup layoffs after the initial round of downsizing many companies undertook at the beginning of the pandemic.

He said startup layoff activity started picking up in mid-March, connected to the Fed’s first interest rate hike (opens in new tab) in more than three years. According to his data, March 2022 saw the highest number of companies conducting layoffs since August 2020.

“In both waves, startups are worried about a cooling fundraising environment and are conducting layoffs to preserve runway regardless of their industry,” Lee said.

Whereas the first round of layoffs mainly hit companies directly impacted by Covid, Lee said this round was driven largely by the increase in interest rates. Affected companies include mortgage startups like Blend, Doma and Better.com, and capital-intensive delivery startups like Gopuff, Avo and SEND that burn lots of cash.

“I expect this to continue until companies can prove they can make money with less headcount,” said Cory Moelis, a general partner with Ground Up Ventures.

Budget Pain on the Horizon?

Colin Yaoskuchi, executive director of the CBRE Tech Insights Center, said tech industry hiring is strongly correlated to the Nasdaq index: “What that’s telling you is that hiring may not be quite as robust over the next 12 months,” he said.

That could further dampen the city’s efforts to revive in-person office work. Workers’ continued avoidance of downtown offices has battered the city’s commercial real estate sector and is viewed by budget analysts as a significant risk to the city’s tax coffers.

For now, both the city and state are running budget surpluses: Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a prospective state budget surplus of nearly $100 billion, more than double the $46 billion estimated earlier this year. Likewise, San Francisco projected a $15 million surplus (opens in new tab) over the next two fiscal years.

David Crane, political scientist and president of the watchdog group Govern For California, cautioned that the state’s calculation (opens in new tab) didn’t properly account for market volatility and pointed out that during the dot-com crash, California’s annual tax revenues fell by more than one-third between 2001 and 2003. If market declines continue, it could spell trouble for the state’s budget.

“Should a similar decline take place today, California’s tax revenues would fall by more than $120 billion over three years—many multiples of the state’s reserves,” Crane wrote in his newsletter on Monday.

San Francisco’s own two-year surplus (opens in new tab) was also buoyed by major returns from the city’s pension system due to the booming stock market; a major reversal in those fortunes could lead to a downward revision.

However, Egan noted that San Francisco’s overall revenue mix is less tied to the public markets than that of the state. Noting that a prolonged downturn would hurt the city fiscally, Egan said that impacts on the city’s budget would come indirectly: For example, companies that earn less revenue may also pay less money in gross receipts taxes.