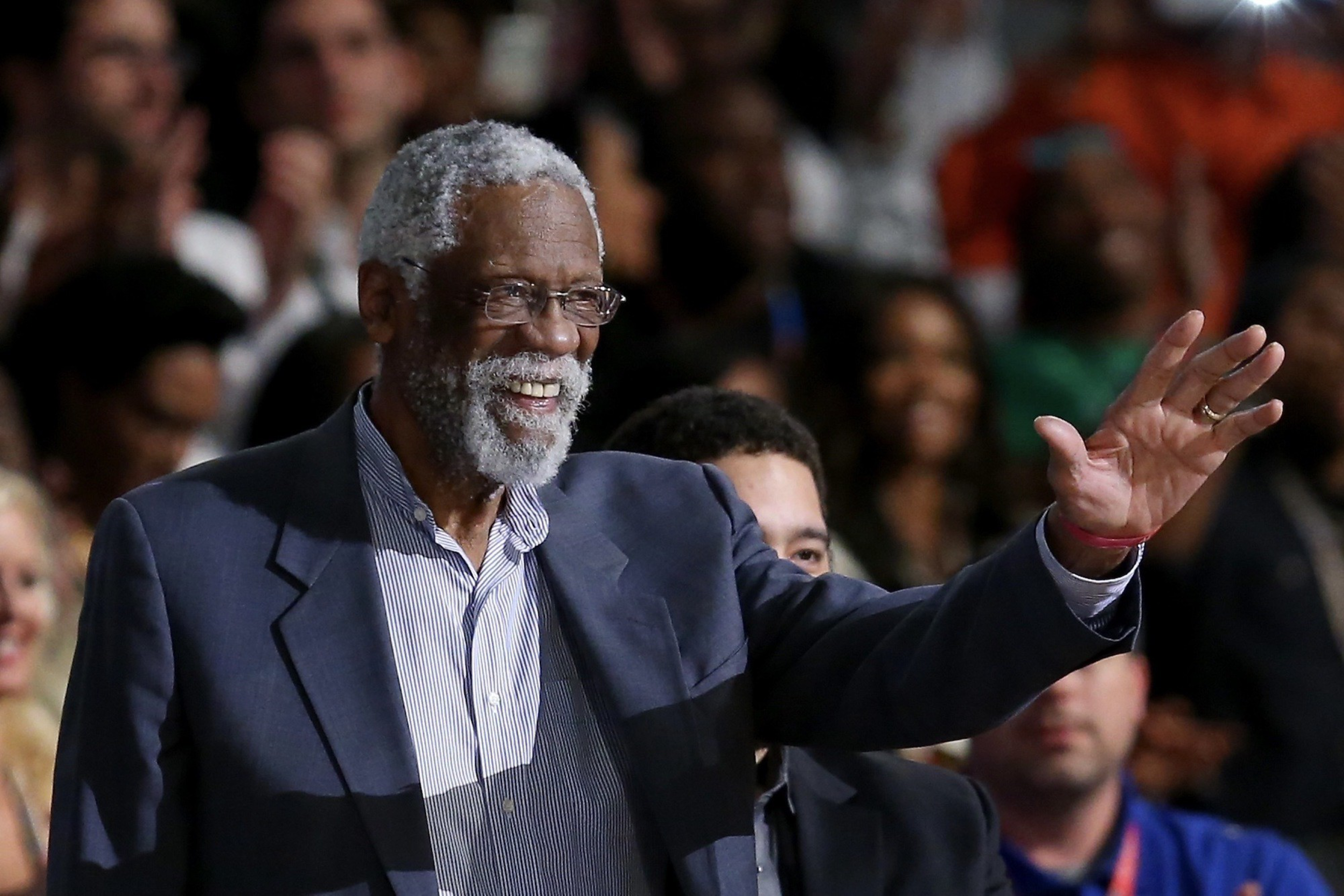

Bill Russell, an 11-time NBA champion who spent much of his formative years in the Bay Area and won two NCAA Tournament Championships at the University of San Francisco (USF), passed away peacefully on Sunday at 88.

Russell leaves an enormous legacy as one of the greatest basketball players of all time and a key figure in the civil rights movement.

He hardly took the typical path to sports fame. Stars like LeBron James may be defined as transcendent generational talents from an early age, but colleges paid little attention to Russell, overlooking the Oakland-based hooper, who moved to the city with his family when he was 8. He only played varsity basketball in his senior year at McClymonds High School, having spent his junior year with the JV team.

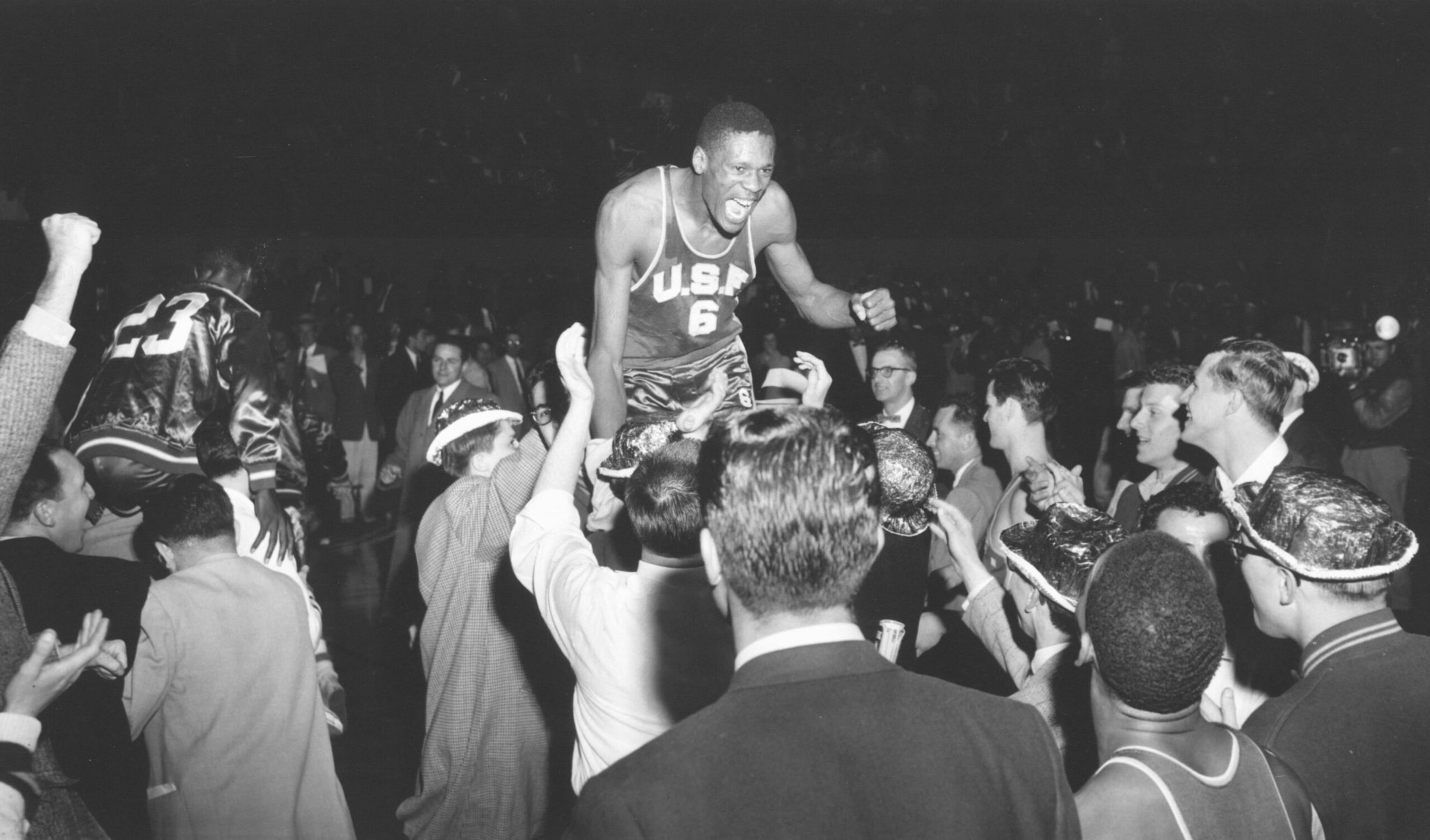

That all changed at USF— the only school to offer him a scholarship—where he both competed as a high jumper and became the starting center under head coach Phil Woolpert after a successful year on the freshman team. He was the leading scorer on a squad that posted a 14-7 record in his sophomore year, then led the Dons to back-to-back national championships in 1955 and 1956, averaging more than 20 points and 20 rebounds per game in each of those seasons.

“Bill Russell helped put USF on the map in the 1950s,” said current university president Rev. Paul J. Fitzgerald. “We are grateful not only for his many contributions to our community, the athletic department and Jesuit education but also for his courage and commitment to advancing justice, on and beyond the basketball court.”

Driven by his accolades, the St. Louis Hawks selected him with the second overall pick in the 1956 NBA Draft. He was quickly traded to the Boston Celtics, where he cemented himself as one of the greatest professional basketball players of all time.

Russell’s NBA career didn’t actually begin until midway through the 1956-57 season, as he opted to maintain his amateur status to participate in the Melbourne Olympics. There, he helped lead the United States men’s basketball team to a gold medal.

In his first playoff game with the Celtics, he racked up 31 rebounds in an Eastern Division Finals win over the Syracuse Royals. And in a winner-take-all NBA Finals Game 7 against St. Louis, he grabbed 32 boards as the Celtics squeaked out a two-point double overtime win to secure their first championship in franchise history.

Despite facing racial abuse from fans, Russell quickly became synonymous with winning in Boston. Though the Hawks bested the Celtics in the 1957 Finals, Boston went on to win the next eight championships. The Celtics topped St. Louis again in seven games in 1960, and while the 122-103 win in the decisive game didn’t require two overtimes like the 1957 edition, Russell racked up 35 rebounds.

Great performances in championship games were commonplace throughout Russell’s career; he had 31 points and 38 rebounds in Game 5 of the 1961 Finals, securing another championship over the Hawks. The Celtics squared off with the Los Angeles Lakers for the first time in the 1962 NBA Finals, and Russell collected 40 boards, matching his own single-game NBA Finals record, in a Game 7 overtime victory. The 1966 series, also against the Lakers, required seven games, and he willed the Celtics to a 95-93 victory with 25 points and a game-high 32 rebounds.

Boston’s dominance was interrupted by the Philadelphia 76ers and longtime rival Wilt Chamberlain in 1967, the first of Russell’s three seasons as a player-coach. Only one other player-coach, Buddy Jeannette of the 1947-48 Baltimore Bullets, has led his team to a championship; Russell did it in each of his final two years. Even as the Vietnam War and other off-court issues compromised his attention during his last season, Russell went out on top in his final campaign, combining with John Havlicek to lead the Celtics to a seven-game NBA Finals victory over the Lakers. Russell had 26 rebounds in his last professional game, a 108-106 road victory that cemented Boston as the first team to win the NBA Finals after losing the first two games.

Russell abruptly retired from both playing and coaching after the 1969 Finals. While he did spend four years in the 1970s coaching the Seattle SuperSonics and dabbled in broadcasting, he was most active after his career in the political arena. Confrontations with racism were a prominent theme in Russell’s life, from his family’s decision to leave Monroe, Louisiana for Oakland in his childhood to discriminatory treatment from journalists and fans.

His activism made him the target of FBI surveillance (opens in new tab); in a file, investigators labeled him “an arrogant Negro who won’t sign autographs for white children.”

Russell boycotted an exhibition game in 1961 (opens in new tab) in Lexington, Kentucky after two of his teammates were denied service in a coffee shop and was a highly visible member of the Black Power movement. Russell was a prominent figure at the Cleveland Summit in 1967 to support Muhammad Ali’s refusal to enter the draft for the Vietnam War.

Bitter feelings over his treatment in Boston (opens in new tab) led Russell to forgo attending his own jersey retirement in 1972 and Hall of Fame induction in 1975. He was, however, present for a ceremony to re-retire his jersey in 1999, 27 years after the initial event. In 2009, the NBA renamed the Finals Most Valuable Player award the “Bill Russell Award,” a fitting honor for a man who went 21-0 in winner-take-all games between his collegiate, Olympic and professional careers.

Regarded as a recluse for much of his post-retirement years, Russell did occasionally take to social media in the final stages of his life, posting about basketball and his travels. But his most memorable contribution to social media came in September 2017, when he posted a photo (opens in new tab) of himself kneeling to show his support for protesting NFL players in the days following then-President Donald Trump’s “get that son of a bitch off the field (opens in new tab)” comments.

Russell is survived by his three children: William Jr., Jacob and Karen. They were born during his marriage to his first wife, Rose. He married three more times. The last of those four marriages was to Jeannine, a competitive golfer 33 years his junior. Jeannine was by his side at the time of his death.